2016-17 Annual Report to Parliament on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act

Real fears, real solutions

A plan for restoring confidence in Canada’s privacy regime

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, QC K1A 1H3

© Her Majesty the Queen of Canada for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2017

Cat. No. IP51-1E-PDF

ISSN: 1913-3367

Follow us on Twitter: @PrivacyPrivee

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PrivCanada/

Letter to the Speaker of the Senate

The Honourable George J. Furey, Senator

Speaker of the Senate

The Senate

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A4

September 2017

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour of submitting to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act for the period from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons

The Honourable Geoff Regan, P.C., M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0A6

September 2017

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour of submitting to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act for the period from April 1, 2016 to March 31, 2017.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Commissioner’s message

The digital revolution, which many have described as the 4th industrial revolution, has brought important benefits to individuals, from ease of communications to greater accessibility of information, products and services that make our lives better materially and intellectually. It is and will continue to be a major contributor of economic growth. However, it is also a cause of great concern. First among these concerns, undoubtedly, is the fear of losing our jobs. Another concern is the fear of losing our privacy, and consequently our inherent right to live and develop as autonomous human beings. Polls consistently show that an overwhelming majority of Canadians (more than 90%) are concerned about their privacy.

The development of technology, which overall is a positive thing, will not take place in a sustainable manner unless the fears of citizens are addressed with concrete and robust solutions. When we held consultations, Canadians told us that when it comes to privacy, they want better information to exercise individual control over their personal information, but they also expect better government protection, because they feel government has more knowledge and better tools to ensure privacy is protected.

I agree with Canadians. In my view, the solutions required to address their concerns should, of course, include better information to empower them to exercise individual control and personal autonomy. But that is not enough. Individuals must be at the centre of privacy protection; however, stronger support mechanisms are also required. This includes among other things, independent regulators, such as my Office, with appropriate powers and resources giving them a real capacity to guide industry, hold it accountable, inform citizens and meaningfully sanction inappropriate conduct.

With that preface, it is my pleasure to present my Office’s 2016-2017 Annual Report to Parliament. This report will cover both the Privacy Act, which applies to the personal information handling practices of government departments and agencies, and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Canada’s federal private sector privacy law.

As was the case when I presented my last Annual Report, the swift evolution of technology—big data, the Internet of Things, biometrics and artificial intelligence, among other innovations—is continuing to have a tremendous impact on personal privacy. It is becoming increasingly difficult for individuals to fully comprehend, let alone control, how and for what purposes organizations collect, use and disclose their personal information.

My Office has been carefully studying this phenomenon, and the need to modernize our privacy regime has never been more apparent or pressing.

Though technology neutral, Canada’s laws were adopted in a much different era when routine, predictable, transparent one-on-one interactions between organizations and individuals were the norm. This is no longer the case in an age where computer algorithms and massive databases drive the economy and open the door to attractive new opportunities for federal institutions and private sector organizations. According to our latest public opinion poll released in January, 92 per cent of Canadians expressed concern about the protection of their privacy and a clear majority (57%) were very concerned.

This is certainly troubling. Something must change or we run the risk that Canadians will lose trust in the digital economy, thus hindering its growth and they may not enjoy all the benefits afforded by innovation. More fundamentally, it is quite unhealthy in a democracy when most citizens fear one of their basic rights is routinely not respected.

In the last year, we have taken a number of concrete steps to address this issue. We have put forward recommendations on Privacy Act reform, Canada’s national security framework and, with this report, the role of consent under the federal private sector privacy law. This report details that work and more, and sets a new course for the future of privacy protection in Canada.

Consent consultation and PIPEDA reform

Consent has long been considered a foundational element of PIPEDA. It is the chief mechanism by which individuals are able to express their autonomy and exercise control over their personal information. Legally, organizations must obtain consent to collect, use and disclose an individual’s personal information, subject to a list of very specific exceptions. But obtaining meaningful consent has become increasingly challenging in the digital age where data has become ubiquitous, commodified and may be processed by multiple players totally unbeknownst to the individual to whom the data belongs.

For this reason, my Office published a discussion paper in May 2016 exploring the practicability of the current consent model under PIPEDA, whether it needs to change and who should be responsible for which changes—organizations, individuals, regulators or legislators.

We received more than 50 written submissions from businesses, civil society, academics, lawyers, regulators and individuals. We also held five stakeholder roundtables across Canada, as well as a series of focus groups with individual Canadians in four cities. After many months analyzing the feedback, we are pleased to unveil our conclusions as part of this year’s annual report.

To begin, we heard how utterly powerless individuals feel in the digital marketplace when it comes to controlling how their personal information is collected and used by companies. Consumers are befuddled by incomprehensible privacy policies, yet feel compelled to consent if they are to obtain the goods or services they desire. Some group participants even said that with the information provided, they are “never” really able to give informed consent.

Still, there was also broad agreement that consent should continue to play a prominent role in privacy protection. After much deliberation, we have presented a number of actions and recommendations intended to make consent more meaningful but also, because consent is not always sufficient as a privacy protection tool, to strengthen the roles of organizations and regulators. Where data-driven practices are likely to make consent impracticable, we have proposed alternatives.

For instance, to make consent more meaningful, we will update our guidance on online consent to specify four key elements that must be highlighted in privacy notices and explained in a user-friendly way. We will also inform individuals of existing consent tools and other privacy enhancing technologies that may assist them in having their preferences respected. We will further draft new guidance for businesses on no-go zones where the use of personal information, even with consent, should be prohibited as inappropriate.

We concluded individuals should not be expected to shoulder the heaviest burden when it comes to deconstructing complex data flows in order to make informed decisions on whether or not to provide consent.

Organizations must also be more transparent and accountable for their privacy practices. Because they know their business best, it is only right that we expect them to find effective ways, within their own specific context, to protect the privacy of their clients, notably by integrating approaches such as Privacy by Design. We will continue, in the course of investigations, to ask organizations to demonstrate how they comply with PIPEDA’s accountability principle, and we will ask Parliament to augment our authority to enforce that principle proactively. We will also adapt our current accountability framework to the needs of small-and medium-sized businesses.

Meanwhile regulators, such as my Office, are well positioned to play a strong role in terms of education and guidance. During our consultations, we were consistently asked to provide more guidance to individuals on how to exercise their privacy rights and to organizations on how to respect their obligations.

This has prompted us to become more citizen-focused. We have already overhauled our website to make it easier to navigate, and are developing new tips sheets and guidance we hope are easier to digest and include concrete advice for people and organizations.

Going forward, we will continue to issue guidance on as many important privacy issues as possible, and will assist industry in developing codes of practice. We will begin by revising our guidance on online consent, but our goal is to provide information on approximately 30 topics within four years. We want to be assessed on how useful our guidance is for individuals and organizations.

In terms of public education, the most effective strategy may well be to teach children about privacy at an early age. We therefore urge provincial and territorial governments to integrate privacy education into school curricula.

We acknowledge that there is a need to encourage innovation and that personal information is an important part of a data-driven economy. In some instances, however, the complexity of the technology, and the uses of personal information and their consequences can pose a real challenge to meaningful consent. To address these realities, we will issue guidance on how to de-identify personal information in a privacy-protective manner. We also encourage Parliament to follow up on a recommendation from private sector stakeholders to address the definition of “publicly available information” for which consent is not required, and to consider whether new exceptions to obtaining consent may be appropriate where consent is simply not possible or practicable.

Search engine indexing websites and big data analytics are just two examples where the volume and velocity of information collection and use may make consent impracticable. A few industry representatives recommended that Canada adopt the concept of “legitimate interests,” which is recognized in European law as a ground for data processing. While this is an option that Parliament may indeed consider, we think such an exception to consent would be very broad. If new exceptions to consent are to be adopted, we believe it would be preferable that they be defined in a more targeted way. We also think they should be subject to strict conditions and apply only in cases where the societal benefits—and not just the benefits to the organization—clearly outweigh the privacy incursions.

Lastly, the role of legislators will be critical to ensuring Canada’s privacy laws stay current and effective in protecting Canadians from risk of harm.

The time has come for Canada to change its privacy protection model to ensure that, as in the U.S., EU and elsewhere, regulatory bodies can effectively protect the privacy rights of citizens by having powers that are commensurate with the increasing risks that new disruptive technologies pose for privacy.

Canadians have told us they are worried. Focus group participants widely favour the notion of government policing businesses to ensure they respect privacy law. They agree that enforcement should be both proactive and reactive. Their views largely mirror the results of our last OPC public opinion poll in which seven in 10 respondents supported granting the Privacy Commissioner order-making power and the potential to impose substantial financial penalties on organizations that misuse their personal information.

Consequently, we are proposing a model that emphasizes proactive enforcement and is backed by order-making authorities and administrative monetary penalties. The model should also clarify the obligation for organizations to demonstrate respect for the principle of accountability.

We are proposing a model that emphasizes proactive enforcement and is backed by order-making authorities and administrative monetary penalties

While Canada’s largely reactive, complaints based model has had a measure of success in the past, it is facing formidable challenges in the digital age. A complaints-driven system does not give a complete picture of where privacy deficiencies may lie. People are unlikely to file a complaint about something they do not know is happening, and in the age of big data and the Internet of Things, it is very difficult to know and understand what is happening to our personal information. My Office, however, is better positioned to examine these often opaque data flows and to make determinations as to their appropriateness under PIPEDA.

A proactive compliance strategy would also allow us to perform voluntary or involuntary audits, as have been conducted for some time by some privacy regulators in other countries and by regulators in fields other than privacy in Canada. These are not extraordinary powers but rather authorities that have been exercised for a long time by other regulators.

That being said, complaint-based investigations will continue in the future, and I will make greater use of my existing power to initiate investigations where we see specific issues or chronic problems that are not being adequately addressed. But these powers are limited and do not authorize my Office to perform proactive audits simply to verify compliance, without grounds that a violation has occurred. These powers would be very useful, indeed necessary, in a field like privacy where business models and data flows are often complex and far from transparent.

In short, we are convinced the combination of proactive enforcement and demonstrable accountability is far more likely to achieve compliance with PIPEDA and respect for privacy rights than the current ombudsman model.

Along the same lines, my Office cannot issue binding orders or impose administrative monetary penalties under the current law. We can merely make non-binding recommendations organizations can take or leave as they wish.

This is not in keeping with the powers of many of our provincial counterparts who have order-making powers, nor of our international counterparts—such as the U.S. and many European countries—who are able to impose financial penalties, which serve as an important incentive for organizations to comply. Legislative changes are urgently needed to give my Office the same powers in order to ensure an effective respect for privacy rights.

I propose these changes knowing that many organizations seek to comply with PIPEDA and make significant efforts to that end. However, not all organizations do, and those who do not, cannot always be brought into compliance through non-binding recommendations and the fear of bad publicity. Penalties would be imposed to promote compliance, not to punish.

I am also unconvinced by the industry argument that changing the ombudsman model would make Canadian companies less competitive. U.S. companies face large penalties if found to engage in unfair privacy practices by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, and they seem able to flourish in that environment.

I am pleased that the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics (ETHI) has embarked on a comprehensive study of PIPEDA. While I made some preliminary remarks before the Committee in February, I very much look forward to returning to discuss our consent report.

Privacy Act reform

This past year we also had an opportunity to present our recommendations for Privacy Act reform to ETHI as part of its statutory review of the legislation.

The 16 recommendations we put forward dealt with technological change, enhancing transparency and legislative modernization. More information on our recommendations for reform of the Privacy Act, is available in this report.

I’m pleased to say that the Committee agreed with all our recommendations in a report issued in December. While government officials understandably have their own objectives when it comes to reform, they too have responded positively to our call for modernization, acknowledging the Privacy Act is in need of a wholesale review.

I was especially pleased when Ministers promised to consider one of our key recommendations—that there be an explicit requirement in law that institutions only collect information that is necessary for the operation of a program or activity—and that pending legislative reform, they would reiterate to federal institutions the importance of complying with the necessity standard, in line with Treasury Board policy.

I look forward to working with the government in the year ahead so that we can breathe new life into the Privacy Act, which has not seen any substantive updates since it came into force in 1983.

That being said, our investigative function under the Privacy Act has kept us extremely busy this past year and we are pleased to unveil our findings in a number of important cases. This includes our report of findings into a series of breaches involving the Government of Canada’s Phoenix pay system and our conclusions following an investigation into the Privy Council Office’s MyDemocracy.ca website aimed at engaging Canadians on electoral reform. The report also discusses an investigation related to the RCMP’s use of cell site simulators, sometimes referred to as “Stingray” devices or “IMSI catchers”.

Public safety, national security and government surveillance

In addition to the future of consent and legislative reform, matters related to national security, public safety and government surveillance have occupied a substantial portion of our time this past year.

In December we participated in the government’s National Security Green Paper consultation. Our submission, prepared jointly with our provincial and territorial counterparts, emphasized how important it is to consider the impact of surveillance measures on rights and addressed issues such as lawful access and the collection and use of metadata by law enforcement and national security agencies; encryption; information sharing by government and oversight.

Generally speaking, we agree that law enforcement and national security investigators must be able to work as effectively in the digital world as they do in the physical. However, that in no way means that legal thresholds and safeguards must be reduced.

To the contrary, safeguards that have long been part of our legal traditions must be maintained, albeit adapted to the realities of modern communication tools, which hold and transmit extremely sensitive personal information. We were pleased to hear Canadians echo our views in their responses to the government’s Green Paper.

In June, the government tabled new national security legislation. We expect to share our views on Bill C-59 with Parliament in due course.

A number of concerns south of the border are also raising difficult questions.

Canadians have reportedly faced deeply personal interrogations when travelling to the U.S. and have been forced to turn over passwords to laptops and mobile phones. We have cautioned people to limit what they bring when travelling, or to remove sensitive information on devices that could be searched.

When U.S. President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order excluding non U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents from the protections of the U.S. Privacy Act regarding personally identifiable information, we received numerous requests to consider the implications for Canada.

We concluded that while Canadians have some privacy protection in the U.S., that protection is fragile because it relies primarily on administrative agreements that do not have the force of law.

Generally speaking, we agree that law enforcement and national security investigators must be able to work as effectively in the digital world as they do in the physical. However, that in no way means that legal thresholds and safeguards must be reduced.

We’ve urged Canadian government officials to ask their U.S. counterparts to strengthen privacy protections for Canadians—namely to ask that we be added to a list of designated countries under the Judicial Redress Act. This would extend certain judicial recourse rights established under the U.S. Privacy Act to Canadians.

We have also asked the government to confirm whether administrative agreements previously reached between Canada and the United States will continue to offer privacy protection to Canadians in the United States. Once we receive a response from the government on this matter, we will provide additional guidance to Canadians to ensure they are well-informed about their rights and how to protect their personal information in the context of international travel.

Our work in the area of national security, public safety, borders and privacy is discussed in further detail in this report. We expect our work in this area to continue in the months ahead.

A final word

Privacy need not be a barrier to innovation, government efficiency or national security, but the pursuit of these objectives is no reason to maintain deficient privacy laws or, more generally, to stick to old ways of doing things.

This is why we want to shift our approach towards proactive enforcement and why we have put forward concrete solutions to the problems related to consent. With adequate funding and resources, we can implement these solutions within our existing authorities.

We have reached a point, however, where this is not enough. If Canada is to remain a global leader on privacy, we must have laws that reflect the realities of the 21st Century.

In June, the government tabled legislation aimed at reforming Canada’s Access to Information law (Bill C-58) and national security oversight regime (Bill C-59). These are two areas that directly implicate privacy and I look forward to sharing our views on these important matters with Parliamentarians.

The government must now address the shortcomings in Canada’s privacy regime. I am encouraged by expressions of interest by Parliamentary committees and cabinet ministers to explore legislative reform as it pertains to both the Privacy Act and PIPEDA.

It is not enough for the government to say that privacy is important while taking no systemic measures to protect it. An overwhelming majority of Canadians are concerned about how the digital revolution is infringing on their right to privacy. They do not feel protected by laws that have no teeth and organizations that are held to no more than non-binding recommendations.

While they expect to derive benefits from innovation, they also expect their privacy to be respected.

Now is the time to instill confidence in Canadians that new technologies will be implemented in their best interest and not be a threat to their rights. Now is the time to reform Canada’s critically outdated privacy laws.

Privacy by the numbers

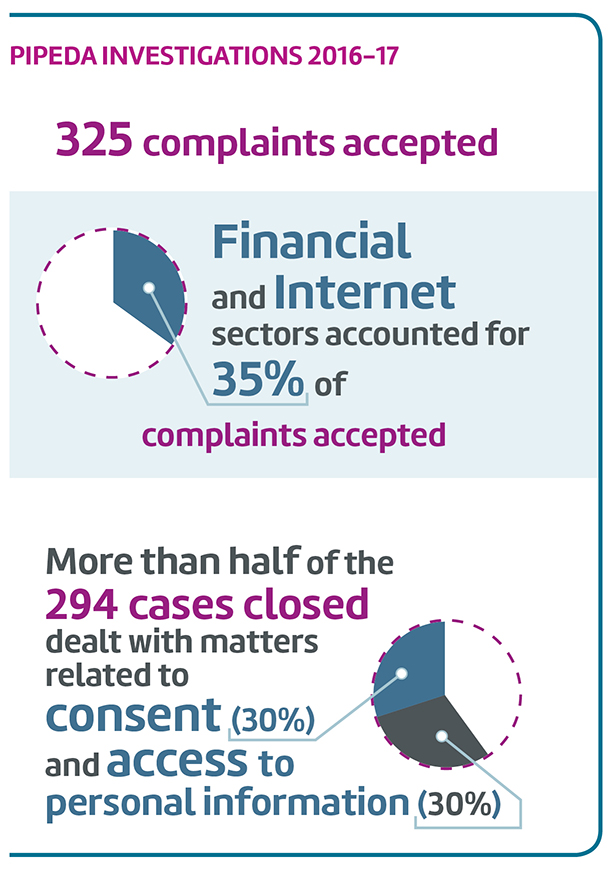

| PIPEDA complaints accepted* | 325 |

|---|---|

| PIPEDA complaints closed through early resolution* | 205 |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through standard investigation* | 89 |

| PIPEDA data breach reports | 95 |

| Privacy Act complaints accepted* | 1,357 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through early resolution* | 423 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through standard investigation* | 660 |

| Privacy Act data breach reports | 147 |

| Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) received | 95 |

| Advice provided to public sector organizations following PIA review or consultation | 49 |

| Public sector reviews concluded | 3 |

| Public interest disclosures by federal organizations | 376 |

| Bills and legislation reviewed for privacy implication | 27 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on private and public sector matters | 13 |

| Formal briefs submitted to Parliament on private and public sector matters | 16 |

| Other interactions with parliamentarians or staff (for example, correspondence with MPs’ or Senators’ offices) | 4 |

| Information requests | 9,091 |

| Speeches and presentations | 123 |

| Visits to website | 2,012,900 |

| Blog visits | 245,583 |

| Tweets sent | 417 |

| Twitter followers as March 31, 2017 | 12,709 |

| Publications distributed | 57,428 |

| News releases and announcements | 50 |

| * includes one representative complaint for each series of related complaints, see Appendix – 2 Statistical tables for more details | |

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act – A year in review

Report on Consent

Widely known as the cornerstone of Canada’s federal private sector privacy law, consent is the tool that affords individuals the opportunity to stake their autonomy and exercise control over their personal information. Organizations that wish to collect, use or disclose that data must, by law, seek and obtain consent. But technological innovations such as big data, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence and robotics have created serious challenges for those on both sides of this transaction. Organizations say that they cannot always pinpoint or predict every reason for which personal information may be used or disclosed in today’s rapidly changing, data-driven marketplace. In this environment, where efforts to explain privacy practices tend to take the form of long, legalistic and often incomprehensible policies and terms of use agreements that are constantly evolving, it is unfair to expect individuals to be able to exert any real control over their personal information or to always make meaningful decisions about consent. Herein lies the dilemma and it’s one that is only expected to get more complicated, not less. The time to act is now.

In May 2016, the OPC published a discussion paper on consent under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) to identify improvements to the current consent model and bring clearer definition to the roles and responsibilities of the various players who could implement them. We received 51 written submissions in response to the paper, with roughly half coming from businesses or associations representing businesses. The balance of submissions came from civil society, academics, the legal community, regulators and individuals. We held five stakeholder roundtables across the country to have in-depth discussions about consent challenges and ways to address them. We also solicited the views of individual Canadians through focus groups held in four Canadian cities. We would like to thank everyone who participated in this effort for their time and their valuable contribution.

In this chapter, we lay out what we heard during our consultation and put forward our recommendations for enhancing consent to ensure PIPEDA can effectively protect Canadians in the 21st century. Our May 2016 discussion paper provides useful background for the concepts discussed below.

What we heard

Many we heard from agreed that the increasingly complex digital environment poses challenges for the protection of privacy and the consent model. There was recognition that consent may be a poor fit in certain circumstances, for example, where consumers do not have a relationship with the organization using their data; and where uses of personal information are not known at the time of collection, or too complex to explain to individuals. While we heard a broad range of opinions on how these challenges should be addressed, most felt nonetheless that consent should continue to have a prominent role in privacy protection.

Business largely emphasized the technology-neutral and flexible nature of PIPEDA, suggesting the current legislative framework is adequate and that there are ways to address consent-related challenges largely without resorting to legislative amendments. Respondents from the advocacy community, including some academics, were more inclined to challenge the status quo and recommended a broader range of solutions to address the perceived shortcomings of PIPEDA and the consent model, including stronger enforcement powers generally .

Focus group participants told us they think about privacy and the protection of their personal information at least to some extent. When it comes to acceptable uses of their personal information by companies, selling or passing this information to a third-party crossed the line.

Focus group participants were dismayed about a perceived lack of control over how their personal information is collected and used by companies. They felt that they had no choice but to consent to practices they did not know much about. They felt unable to inform themselves because they find the information provided by organizations to be vague, complex and nearly impossible to understand. They were particularly concerned about disclosure to third parties and expected very clear language on this point before giving consent. They wanted better information to exercise individual control but also expected better government protection, because government has more knowledge and better tools to ensure privacy is respected.

Below are specific comments and suggestions that we heard, followed by the OPC’s response in terms of action plans and recommendations.

Enhanced consent

Many participants expressed views about the importance of consent and the role alternatives to consent might play in the future. Those who believed most strongly in consent viewed privacy as protecting individuals’ right to decide for themselves what happens to their personal information, and consent as the means to exercise autonomy. Some felt that challenges to consent stem not from the notion of consent itself, but how it is put into practice. We also heard that consent should be an ongoing process, rather than a one-time, all or nothing choice. It was noted, however, that consent may place too much responsibility on individuals in some situations, such as big data algorithmic processing which can be far too complex for non-experts to understand and where future uses of information may not immediately be known.

Form of consent

We heard much discussion about the form of consent required. It was suggested that the OPC provide further clarification as to when express consent is required and when implied consent may be acceptable. Some proposed that purposes that are not immediately obvious should require opt-in. Conversely, some suggested that consent for the collection of personal information directly required for the good or service could be implied, with limited exceptions. We also heard that the types of notices and choices provided should be directly linked to the sensitivity of information or the risk of harm of a data processing activity. Some suggested that the OPC should widen the scope of implied consent while at the same time placing greater accountability on organizations for their handling of personal information.

Simplified privacy policies

Although a few written submissions recommended the use of shorter and/or standardized privacy policies, overall we heard little support for generic policies or templates. It was generally felt that privacy practices must be described in the specific context of the service being provided in order to be useful. It was noted that even within an industry sector, it would be challenging to identify generic privacy practices. We heard that organizations should strive to highlight up front the core information individuals will look for when being asked for consent. This would include what information is being collected, and what it will be used for, who it will be shared with and for what purposes. Particular prominence should be given to unexpected risks or potentially harmful practices. It was suggested that the OPC could clarify best practices through guidance or codes of practice.

Many participants liked shortened or layered privacy policies. One common suggestion was to allow organizations to highlight only those practices that deviate from the norm while filtering out standard regulatory requirements common across the industry and/or lengthy explanations of practices that would or should be obvious to users in light of the service provided. Others were in favour of real-time consent notices and using infographics, videos, and bots to supplement the information provided through privacy policies. Some called for more research into innovative mechanisms for conveying privacy information.

There was some criticism of privacy policies in general, which were likened to contracts of adhesion due to their “take-it-or-leave-it” nature. We heard that it is important to seek consent at the right time in the process in order for it to be meaningful. Focus group participants generally bemoaned the fact that accepting the terms and conditions is the cost of doing business with companies. In their view, consent is rarely if ever informed. It is an all or nothing scenario over which they have no control.

Technological solutions

Technological solutions to enhancing consent were generally viewed with optimism, though some felt that these were still relatively nascent in a fast-changing digital environment.

Among the solutions presented in written submissions was “tagging” data as a mechanism for restricting its collection, use, disclosure, and retention. Another concept referenced was the use of “consent receipts” to exert control over future choices. There were also recommendations for dashboard/portals to control and adjust privacy settings. One submission suggested that technical measures could be adopted to mask or conceal certain data elements, thereby protecting only that data which needs to be protected, and allowing other data elements to be freely used.

We heard that technology could help manage complexity and that metrics could be adopted to measure consistency on a company’s data management practices with individuals’ consent preferences. It was suggested that the OPC identify the best existing solutions among different approaches such as privacy signaling tools, choice dashboards, infrastructure, database structure and transparency tools. We also heard that the OPC should strongly encourage the tech giants to bake consent-enhancing solutions into their operating systems.

De-identification

Many participants appeared to view de-identification as beneficial to privacy but not without significant risks. On the one hand, the process of de-identification can be used to strike a balance between protecting personal information and the organizations’ desire to use personal information in new and innovative ways. On the other hand, there were concerns that it may simply not be possible to render personal information fully non-identifiable without any residual risk of re-identification.

A number of participants from industry and the legal community argued that de-identified information is not personal information, it falls outside PIPEDA’s framework, and consent is therefore not required for its collection, use and disclosure. Others, including representatives from academia and civil society, felt that PIPEDA should continue to apply even to de-identified information, given the real and growing risks of re-identification and the need to ensure organizations remain accountable for their use of de-identified data, including responsible purposes and appropriate safeguards. Some participants saw de-identification and contractual backstops against re-identification as useful strategies for minimizing the risks of unauthorized collection, use, and disclosure of personal information but not necessarily as an alternative to consent.

Industry representatives called for guidance from the OPC on issues such as methods of de-identification and assessing the risk of re-identification, to supplement existing guidance from other data protection authorities. This would help organizations lower the risk of re-identification and achieve better balance between privacy protection and commercial purposes.

Privacy by design and privacy by default

Generally, stakeholders expressed support for Privacy by Design (PbD) and felt it should be encouraged. However, they cautioned against an overly prescriptive approach as this could risk hampering innovation and competitiveness. Industry held the view that although a sound guiding principle, PbD does not need formal integration in law as it is already recognized as a best practice.

Privacy by default on the other hand was less universally accepted. Some felt that privacy by default would maximize user control while others felt it would be cumbersome and interfere with the practical and seamless use of a product or service. Many felt that privacy controls were dependent on the type of service being provided and should reflect the personal preferences of individuals, who have various levels of comfort with sharing their personal information.

No-go zones

Generally speaking, there was little support for specifically legislated no-go zones. The concept of no-go zones is based on the belief, recognized in section 5(3) of PIPEDA, that the collection, use and disclosure of personal information should be prohibited outright in certain circumstances regardless of whether consent is obtained. Generally, section 5(3) of PIPEDA was viewed as robust and flexible enough to address “no-go” type situations without having to prescribe them in law. Some cautioned against imposing too much regulation in a fast-changing environment or resorting to top-down protections rather than empowering individuals, though it was recognized that certain practices, such as unauthorized listening through connected devices, were particularly objectionable and inappropriate.

Some civil society groups favoured no-go zones and even suggested examples of prohibited uses to consider, including i) recording sound from a user’s microphone or camera, except in cases where a user is using the microphone or camera as part of obtaining services from the site; ii) publishing personal information for the purpose of incentivizing individuals to pay for the removal of their information; and, iii) attempting to re-identify a user in anonymized data.

Legitimate interests

There was limited support for legitimate interests as a new ground for processing while recognizing that in some situations, the boundaries of consent are being stretched beyond their limits. For example, it was noted that intermediaries like search engines cannot possibly seek consent as a condition for returning billions of search results each day that may or may not contain individuals’ personal information. Also, in a big data context, opportunities are constantly emerging to analyze huge volumes of data originally obtained for one purpose, combined with a variety of other data sources in search of new, innovative possibilities; yet such possibilities cannot always be anticipated at the time of original collection, nor is it always practicable or even possible to recontact each individual in order to obtain fresh consent, as is required under PIPEDA.

Many civil society groups and academics were concerned that a legitimate interest approach would significantly reduce individual control as it is too open-ended. They were skeptical of the idea of importing into PIPEDA a European concept that is rooted in an entirely different legal framework. They commented on the European context that contains much stronger complementary protections currently lacking in PIPEDA.

For their part, industry did not strongly support the concept either. We heard that a better option might be to stretch implied consent because consent can be withdrawn, whereas legitimate interest cannot be revoked. There were also arguments in favour of a broad description of purposes (such as "improving customer service") which would authorize organizations to use the information for purposes not known at the time of collection. Others felt the time has come to recognize the limits of consent and that a new concept might be required to balance industry needs and privacy protection.

Some were not opposed to the concept of legitimate interests but were concerned that if organizations alone were to define it, profit-making might prevail to the detriment of individual and public interests. A possible solution might be to require that the rationale for a legitimate interests decision be disclosed to the regulator and/or vetted by some third party.

Ethics

While a few submissions supported ethical assessments and frameworks, including the creation of independent third-party ethics boards, participants at stakeholder meetings—whether from industry or civil society or other regulators—were generally skeptical of the idea.

Some participants thought this approach was potentially paternalistic by allowing ethics board members to speak on behalf of individuals. Others were concerned about the operational feasibility of ethics boards, either because they would be too onerous for small business or would create needless red tape. While some large companies have already begun instituting internal ethics advisory boards, some thought it unlikely that organizations would agree to disclose confidential commercial information to outside third parties or be bound by external advice. Others suggested that there are other ways to address unethical uses of data, for example through subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA or through enhanced enforcement.

Enforcement

Stakeholder groups had diverging opinions on the need for stronger enforcement powers for the OPC. Organizations largely felt that there is no need to increase OPC powers. Some felt that the threat of public interest naming is already effective in bringing organizations into compliance because of the reputational harm this can cause to organizations. It was noted that increased powers would increase organizations’ compliance costs significantly and enforcement should be done in the most cost-effective way possible to avoid suppressing innovation. Some felt that stronger enforcement is not the solution because Canadian organizations tend to have a desire to comply with PIPEDA; and cautioned that stronger powers might cause organizations to resist innovating out of fear of non-compliance. Others felt that more outreach to organizations to increase their awareness of PIPEDA requirements would lead to better compliance than would enforcement-related compliance.

Civil society participants and academics generally called for stronger enforcement powers, arguing that self-regulation currently does not work. Some thought enforcement is the most effective tool for influencing privacy-compliant behavior and yet, there is too little enforcement. It was noted that CEOs inevitably pay more attention and invest more compliance resources in areas where they risk facing enforcement by domestic or international regulators who have stronger authority to make orders and impose fines.

Canadians have said they want a privacy commissioner who can enforce privacy laws with order-making powers and the ability to impose fines.

Consumers clearly expect stronger enforcement in all forms, including orders, fines and audits. We heard that in some situations, complaints are unlikely to be filed and therefore the regulator needs to be more proactive in monitoring compliance. There were calls for a lowering of thresholds for audits. Self–auditing by companies was also suggested. However, some organizations objected to what they viewed as a reversal of the burden of proof under a proactive audit system.

Some suggested that the OPC provide preliminary opinions on a company’s proposed practice upon request. A civil society organization recommended that the Commissioner should be empowered to issue “comfort letters”, at a business’s expense, providing its preliminary opinion as to whether a proposed practice would comply with PIPEDA.

Education

Focus group participants expressed a widespread desire for information government could provide by way of outreach/public education on privacy-related matters, including what to look for in a privacy policy and what information not to share.

Focus group participants expressed a widespread desire for educational materials on privacy-related matters. Information considered most helpful included: what to look for in a privacy policy, what data not to share with businesses, what the government does to protect personal information, and individuals’ rights and obligations.

Stakeholders also supported public education efforts, although some cautioned that education should not be used to offload privacy responsibilities onto individuals.

Many stakeholders commented on the value of OPC guidance and recommended that the OPC issue additional guidance. Topics of interest included de-identification, forms of consent, and practical tools aimed at small and medium businesses. There was also a strong call for OPC guidance to clarify OPC expectations for compliance in specific areas, such as smart cars.

We heard that both the OPC and organizations have a responsibility to identify norms that would be acceptable to most individuals. It was suggested that good practice be rewarded in order to offset the perception that privacy impedes innovation and adds complexity.

Codes of practice were discussed as a way of providing clarity to organizations on their legislative responsibilities and reassurance to individuals that organizations adhering to the codes are meeting their privacy obligations. Stakeholders were divided about the value of codes of practice. From business we heard that “one-size-fits-all” sectoral codes of practice do not reflect the diversity of practices and needs of businesses in the digital economy. However, there was support for activity-based codes developed with input from the target stakeholders.

We heard that organizations should be responsible for leading code of practice initiatives as they know their business best but may need some encouragement to do so. Codes of practice can be used by good businesses to nudge bad actors into compliance and towards a higher standard. This could also encourage a culture of respect for privacy, which is good for organizations’ reputations and building consumer trust.

Our view

Consent remains central to personal autonomy, but in order to protect privacy more effectively, it needs to be supported by other mechanisms, including independent regulators that inform citizens, guide industry, hold it accountable, and sanction inappropriate conduct. Alternative privacy protection tools must also be considered in exceptional and justifiable circumstances where consent is simply not possible or practicable.

Consent remains central to personal autonomy, but in order to protect privacy more effectively, it needs to be supported by other mechanisms, including independent regulators that inform citizens, guide industry, hold it accountable, and sanction inappropriate conduct.

Consent is a foundational element of PIPEDA. Legally, organizations must obtain meaningful consent to collect, use and disclose an individual’s personal information, subject to a list of specific exceptions. When PIPEDA was adopted, interactions with businesses were generally predictable, transparent and bidirectional. Consumers understood why the company they were dealing with needed certain personal information. There were clearly defined moments when information collection took place and consent was obtained. But obtaining meaningful consent has become increasingly challenging in the digital environment.

In the consent discussion paper, we described the many challenges new technologies and business models are bringing to PIPEDA’s consent model. Reliance on opaque privacy policies as the basis for consent, complex information flows, and business processes involving a multitude of third-party intermediaries, such as search engines, platforms and advertising companies, have put a strain on the consent model. In this age of big data, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence and robotics, it is no longer entirely clear to consumers who is processing their data and for what purposes. For individuals, the cost of engaging with modern digital services means accepting, at some level that their personal information will inevitably be required to be collected and used by companies in exchange for a product or service.

As such, the practicability of the current consent model has been called into question. Nonetheless, we are of the view that there remains an important role for consent in protecting the right to privacy, where it can be meaningfully given with better information. We’ve heard a broad range of suggestions from stakeholders and focus groups on how consent can work better.

Situations in which consent may be simply impracticable are likely very specific, for example, intermediaries where there is no relationship between an individual and the organization collecting and using personal information, such as search engines. Meaningful consent may also be impracticable (or at the very least challenging) in the case of big data initiatives or Internet of Things devices that individuals have no choice but to use. It is conceivable that technology may function in such a way as to defy understanding of how personal information is being processed or what the consequences may be, undermining the meaningfulness and validity of informed consent.

Where consent may not be practicable, the challenge then centres on what can be done to maintain effective privacy protections in the face of ever-changing pressures from technology, business and society, and to identify improvements required to the way consent functions currently.

Technological changes bring important benefits to individuals. They greatly facilitate communication, make available a wealth of information, and give access to products and services from all areas of the world. However, technologies also create privacy risks. Effective privacy protection is essential to maintaining consumer trust and enabling a robust and innovative digital economy in which individuals feel they may participate with confidence. New technologies also hold the promise of important benefits for society, and future economic growth will come in large part from the digital economy. For instance, Canada is well placed to become a world leader in artificial intelligence, which depends on the collection and use of massive amounts of data. The federal government has already invested heavily in this area based on the great potential for return on investment. At the same time, Canada has signed the 2016 OECD Ministerial Declaration on the Digital Economy committing among other things, to an international effort to protect privacy, recognizing its importance for economic and social prosperity.

An overwhelming majority of Canadians is concerned. They have real fears. Now is the time to give them confidence that new technologies will serve them and not be a threat to their rights.

Yet, according to the OPC’s 2016 Survey of Canadians on Privacy, the vast majority of Canadians are worried that they are losing control of their personal information, with 92% of Canadians expressing concern, and 57% being very concerned, about a loss of privacy. Without significant improvements to the ways in which their privacy is protected, Canadians will not have the trust required for the digital economy to flourish and will not be able to reap all the benefits made possible through innovation. One of the OPC’s strategic goals is to enhance the privacy protection and trust of individuals so that they may confidently participate in an innovative digital economy, hence our focus on consent.

The absence of strong privacy protections will likely have societal consequences as well. Internet users want to express themselves, explore others’ views and search sensitive issues like health without fear that these activities will embarrass them, be turned against them or shared with others with adverse interests. Privacy and informed consent help support our democratic system where individuals have agency to exercise their right to autonomy, including the right to make choices and express preferences. We need to critically examine any situations that threaten to subvert our autonomy and work to create an environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatmentFootnote 1.

In attempting to identify solutions that would serve to enhance privacy protections today and going forward, we were faced with the central dilemma of how the responsibility for protecting privacy should be apportioned among the various actors—individuals, organizations, regulators and legislators. We heard a compelling opinion from one stakeholder that individuals have to remain at the centre of privacy protection but they need trusted third parties such as regulators to play a more proactive role in further protecting their interests.

Indeed, in the current digital ecosystem, it is no longer fair to ask consumers to shoulder all of the responsibility of having to deconstruct complex data flows in order to make an informed choice about whether or not to provide consent. Autonomy is very important but, given the complexity of the environment, there is a strong role for regulators who have the expertise to enhance privacy protection through education and proactive enforcement. Organizations too must be transparent about their practices and respectful of individuals’ right to make privacy choices. And legislators need also to step in when laws are no longer meeting the very objective they set out to achieve and are no longer effective in protecting Canadians from risk of harm.

In other words, everyone—individuals, organizations, regulators and legislators—needs to play their part for privacy to be protected effectively. As stated in the consent discussion paper, the burden of understanding and consenting to complicated practices should not rest solely on individuals without having the appropriate support mechanisms in place to facilitate the consent process. Accordingly, we propose the following solutions for consideration by all the relevant players.

Making consent more meaningful

Privacy notices

To tackle the situations where obtaining consent is challenging, it is important to first address where and how existing consent mechanisms can be improved. Many situations, including those involving emerging technologies and business models, will continue to require an individual’s consent. In order for consent to be valid, individuals must be able to understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information. Even though privacy policies are not mentioned in PIPEDA, most companies have chosen to use the privacy policy or terms of use as the primary vehicle for obtaining informed consent, as well as satisfying various other legal and regulatory requirements. This was a questionable choice from the beginning and these documents continued to grow longer and more complex over time. The problem was compounded as companies moved online and largely failed to adapt their privacy notices to a digital environment. Instead they have simply transferred a static, point-in-time, analog document into electronic form.

During the consultations, privacy policies were heavily criticized for obfuscating data practices by being overly lengthy, using complex and ambiguous language, and generally failing to provide individuals with a clear description of how their personal information is to be managed. Individuals talked about the complexity, lack of clarity, and all-or-nothing approach of consent mechanisms. Based on what we heard, in the mind of the average person, privacy policies are broken. Many of our focus group participants had no clear or definite idea of what it means when a company has a privacy policy and most admitted to not reading them.

Much time was devoted to discussing how to fix privacy policies. Suggestions put forward ranged from highlighting unexpected uses of personal information to multimedia and interactive policies. We agree that privacy policies have been ineffective from a consent perspective, but nevertheless they serve a range of important legal purposes. They are the foundation for the current contractual notice-and-consent model. In addition, regulators and others need to refer to privacy policies in order to hold organizations to account for their personal information management practices and other legal obligations.

Privacy policy principles

While we did hear calls for the OPC to develop templates for privacy policies specific to different sectors, we do not believe that should be the role of a regulator. Rather, it is best left to organizations to find innovative and creative solutions to the consent process in a manner that respects the nature of their relationship with consumers. However, in so doing, we encourage organizations to be guided by the following principles:

- Information provided about the collection, use and disclosure of individuals’ personal information must still be readily available in complete form, although, to avoid information overload and facilitate understanding by individuals, certain elements warrant greater emphasis or attention in order to obtain meaningful consent (see elements below).

- Information must be provided to individuals in manageable and easily-accessible layers, and individuals should be able to control how much more detail they wish to obtain and when.

- Individuals must be provided with easy “yes” or ‘no’ options when it comes to collections, uses or disclosures that are not integral to the product or service they are seeking.

- Organizations should design and/or adopt innovative consent processes that can be implemented just in time, are specific to the context and appropriate to the type of interface used.

- Consent processes must take into account the consumer’s perspective to ensure that they are user-friendly and that the information provided is generally understandable from the point of view of the organizations’ target audience(s).

- Organizations, when asked, should be in a position to demonstrate the steps they have taken to test whether their consent processes are indeed user-friendly and understandable from the general perspective of their target audience.

- Informed consent is an ongoing process that changes as circumstances change; organizations should not rely on a static moment in time but rather treat consent as a dynamic and interactive process.

We will update our guidance on online consent to specify four key elements that must be highlighted in privacy notices and explained in a user-friendly way.

As stated in the 2014 joint guidelines for online consent, the consent obtained by organizations must be based on complete and understandable information and therefore that information must be readily available. However, we believe that certain elements in particular should be given more prominence in order to obtain meaningful consent. These are:

- what personal information is being collected;

- who it is being shared with, including an enumeration of third parties;

- for what purposes is information collected, used, or shared, including an explanation of purposes that are not integral to the service; and

- what is the risk of harm to the individual, if any.

Organizations should deliver the right information to individuals when they most need it. This includes using meaningful language and going beyond vague descriptions of purposes such as “improving the customer experience.” We recognize the difficulties of finding the sweet spot between delivering information required for users to make informed decisions and not disrupting the flow of their experience or causing consent fatigue. Nonetheless, it is only when the right information is brought to individuals’ attention at the right time and in a digestible format that they can exercise meaningful control.

In the course of our compliance activities, we will continue to require organizations to provide complete information, but we will also expect that additional emphasis be given to the above-mentioned four elements. We have updated the online consent guidance to provide more clarity around these expectations, and are welcoming comments on this proposed change.

Forms of consent

Stakeholders also had questions about what form of consent should be required in a given situation. We heard from stakeholders that consent should be explicit for proposed practices that are not core or integral to the service, or that are unexpected or out of context. At the same time, individuals do not want to be asked too often for express consent. Again, we recognize that consent fatigue is against everyone’s interest, individuals and businesses alike. The courts have affirmed that in determining the form of consent to use, organizations need to take into account the sensitivity of the information, and the reasonable expectations of the individual, both of which will depend on the contextFootnote 2. We will consider how best to flesh out the concept of reasonable expectations of individuals in different contexts. This may mean working with organizations and individuals to examine what personal information they view as integrally linked to their services, and we will expect organizations to be very transparent about when personal information is core or integral to the service and when it is not.

We also agree with stakeholders that the form of consent should depend on the sensitivity of the information and the risk of harm of a data processing activity. PIPEDA refers to sensitivity, but it does not refer specifically to risk of harm. Yet we see risk of harm as an important and related factor to consider when assessing the sensitive nature of personal information in a given context. We will therefore amend our consent guidelines accordingly, and we will ask Parliament to make risk of harm an explicit factor to consider when determining the appropriate form of consent.

Children and youth

During the consent consultations, some stakeholders asked for guidance in applying PIPEDA’s consent requirement to children. We believe that a child’s ability to provide meaningful consent is a function of individual maturity which we recognize is an evolving process of cognitive and social development. While a child’s capacity to consent can vary from individual to individual, we believe that there is nonetheless a threshold age below which young children are not likely to fully understand the consequences of their privacy choices, particularly in this age of complex data-flows. As such, we are taking the position that, in all but exceptional cases, consent for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information of children under the age of 13, must be obtained from their parents or guardians. As for youth aged 13 to 18, their consent can only be considered meaningful if organizations have taken into account their level of maturity in developing their consent processes and adapted them accordingly. Our draft online consent guidelines will propose guidance on this issue.

Encouraging consent technologies

Technology has a role to play when traditional attempts at providing meaningful consent have failed. It has the potential of facilitating the consent process and making it more practical and meaningful. The OPC’s consent stakeholder sessions and submissions discussed a number of technical solutions that could enhance the consent process. We believe that there is no shortage of technologies or good ideas for facilitating the consent process, but there does seem to be a lack of deployment and adoption in the business community. The current economic and regulatory environments provide little incentive for deploying promising consent technologies, so further development of technology alone is not likely to lead to significant changes.

To raise awareness of available consent technologies and encourage their use by individuals, the OPC will publish education material identifying various consent technologies available on the market today. We will also find ways to fund research and knowledge translation activities to promote development and adoption of consent technologies by industry through the OPC’s Contributions Program. The OPC also plans to explore opportunities to take an active role in standard-setting bodies and industry groups.

We believe that companies should assist individuals in making privacy choices. We are particularly concerned by reports that companies may be complicit in establishing an environment that disregards or counteracts individuals’ use of consent technologies. For example, certain types of tracking used in online behavioural advertising cannot be stopped or controlled without taking extraordinary measures (and some cannot be stopped or controlled at all). These include so-called zombie cookies, super cookies, and device fingerprinting. To that end, we would encourage individuals to advise us of any such problems they encounter when they attempt to make use of these new consent technologies but see their choices being overridden nonetheless. We will pursue issues reported to us where we find reason to believe that individuals’ privacy choices are not being respected or are being reversed against their wishes. More broadly, there is an opportunity for government involvement in this area. As part of its strategy to promote the development and adoption of innovative technologies, like artificial intelligence or superclusters, we encourage government to fund technologies on the condition that they build in privacy protections. In our view, there is an opportunity for the government to leverage innovation and better privacy protections across the board.

No-go zones even with consent

One of the questions we put to stakeholders is whether they see a need to amend PIPEDA (or other legislation) to introduce clear and specific prohibitions on the use of personal information even with consent (so called “no-go zones”). PIPEDA already prohibits inappropriate uses under subsection 5(3), which cannot be overridden by consent, but these are broad and subject to interpretation.

We agree with stakeholders that legislating specific no-go zones would not be ideal, given the fast pace of change and innovation. However, we do intend to issue guidance under subsection 5(3) to provide greater clarity to organizations on what we consider inappropriate uses from “the reasonable person standpoint,” which we believe would also be useful to consumers. We will be releasing a draft version of this guidance and seeking input before finalizing it. Our draft is informed by comments we heard during the consultations, as well as our experience investigating privacy practices and listening to Canadians’ concerns over the past 15 years. Some examples of what we consider to be purposes that a reasonable person would not consider appropriate are: collection, use or disclosure that is otherwise unlawful; profiling or categorization that leads to unfair, unethical or discriminatory treatment; publishing personal information with the intended purpose of charging individuals to pay for its removal; and situations that are known or likely to cause significant harm to the individual. By “significant harm,” we mean both material and reputational harm as is contemplated in the new subsection 10.1(7) of PIPEDA, which has been adopted but is not yet in force.

Although privacy, as an inherent right, can be infringed without harm, some stakeholders made mention of the important role of harm in privacy protection. We agree that mitigating the risk of harm is one of the aims of privacy legislation and, as noted earlier, we think that it should be made explicit under the law. Specifically, where collection, use or disclosure of personal information is known or likely to cause significant harm to individuals, it should be prohibited. On the other hand, where risk of harm is lower and reasonable in return for a benefit, the choice to accept or not should be left to the individual. In order to inform these trade-off decisions, risks must be fully disclosed, and individuals’ acceptance of those risks must be expressed explicitly.

Guidance for individuals and organizations

Privacy protection starts with knowledge. For individuals this means being able to identify privacy risks, having the skills to mitigate them, and knowing how to exercise their privacy rights. For their part, organizations need to know their privacy obligations, and understand what is expected of them with some sense of consistency and predictability in order to comply with the law.

During the consent consultations, stakeholders overwhelmingly called on the OPC to provide more education and guidance for individuals and organizations and we agree that this is an integral part of addressing not only the consent challenge but ensuring effective privacy protection as a whole. We heard that businesses look to the OPC to develop and promote good privacy practices and provide clarity around PIPEDA requirements. Guidance is particularly useful to small- and medium-sized businesses that typically have a lower awareness of PIPEDA and lack the resources to address privacy effectively.

Focus groups expressed a widespread desire for information on privacy-related matters. This includes what to look for in a privacy policy and how to address the risks associated with sharing personal information with companies. As part of the OPC’s public education mandate, we have a strong commitment to helping raise awareness of privacy issues and to providing individuals with information to help exercise their privacy rights and reduce privacy risks. Public education also has the added benefit of empowering consumers themselves to play a challenge function and hold companies to account through questions and complaints.

However, it is important to recognize that privacy education does not just benefit consumers. All Canadians, regardless of their role in the economy, need to become digitally literate so as to exercise their privacy rights and have control over their personal information. Children in particular need to be educated about privacy and its value to individuals and our society in order to make informed decisions.

The OPC’s particular focus in education materials has been on helping equip children and young people with the skills to evaluate and mitigate privacy risks and to make informed privacy choices. To that end, we have developed resources for parents, educators and librarians, such as lesson plans, fact sheets and a graphic novel to help bring privacy education to kids. Internationally, we helped develop the 2016 Marrakech Resolution calling for the adoption of a competency framework for privacy education in schools. Currently we are participating, through the International Working Group on Digital Education, in efforts to further the inclusion of privacy and data protection skills in the education of students around the world.

While we are proud of our work to date in this area, as a federal body we face jurisdictional limits to our ability to influence education. We note that our provincial and territorial counterparts have expressed similar concerns about the need to improve digital education. Together, we are asking that privacy education should be made an official part of the curriculum starting as early as possible. Kindergarten to grade 12 education reaches nearly all Canadians and while some provincial curricula may touch on privacy skills to some degree, the need to promote privacy literacy in a holistic and consistent manner should not be ignored. We are ready to support our provincial and territorial colleagues to help institutionalize privacy education so that children are empowered to protect their privacy from a young age and stand ready to participate fully in the digital world with knowledge of the value of privacy and the skills to exercise their privacy rights.

Beyond school curricula, privacy education and guidance for individuals figures prominently in our action plan for improving Canadians’ control over their privacy, across the age spectrum, including seniors. To that end, we have identified a series of topics where we think Canadians would benefit from privacy information. We intend to issue guidance and fact sheets in as many areas as possible in order to help Canadians have a better understanding of privacy implications and have more agency in exercising their privacy choices. We have also identified topics where we intend to issue guidance or update existing materials aimed at businesses to help provide clarity and certainty around particular issues or practices:

- Consent (including forms of consent)

- Subsection 5(3) no-go zones

- De-identification

- Big data, artificial intelligence & robotics

- Genetic information

- Internet of Things

- Connected cars

- Smart homes

- Privacy enhancing technologies

- Surveillance technologies

- Privacy at the border (smart borders)

- Necessity and proportionality in the public sector

- Online reputation

- Privacy and social media

- Educational apps/platforms

- Biometrics & facial recognition

- Cookie-less tracking

- Blockchain

- Digital health technologies

- End-to-end encryption

- Social engineering

- Trans-border data flows & cloud

- Open government

- Accountability maturity model

- Breach notification

- Data brokers

- Fintech

- Sharing economy

- In-store tracking

- Behavioral economics

While we cannot promise to fulfil this wish list as quickly as we would like, we will undertake to complete as much as we can by 2021, taking into account our workload and resources. Recognizing that we cannot do it all in the near future, we will begin in the next two years with those areas where we see the greatest need directly related to the issue raised in this chapter: online consent, subsection 5(3) no-go zones, de-identification and privacy enhancing technologies, genetic information and breach notification, in addition to our parallel work on online reputation, biometrics and the border. We will also publish research on artificial intelligence.

Moreover, we will encourage industry to help us by developing codes of practice in some key areas. To start, we are funding two research projects through our Contributions Program that will seek to develop codes of practice on the connected car and legal apps, and we hope to expand on this in the foreseeable future. Codes of practice are a useful and effective tool for enhancing compliance.

OPC Actions

- The OPC will issue updated guidance on online consent that will set the following expectations:

- While organizations must continue to make readily available to individuals complete and understandable information, the following elements must, in order to obtain informed consent, be given particular prominence and be brought to the individual’s attention in a user-friendly format and at an appropriate time:

- what personal information is being collected;

- who it is being shared with;

- for what purposes is information collected, used, or shared, including an explanation of purposes that are not integral to the service; and

- what is the risk of harm to the individual, if any.

- In determining the form of consent, organizations must consider the reasonable expectations of the individual, the sensitivity of the information and the risk of harm.

- The OPC will also amend its accountability guidelines to clarify that organizations give prominence to a few key pieces of information and that they be able to demonstrate that they have a process in place to verify that their consent mechanism works.

- While organizations must continue to make readily available to individuals complete and understandable information, the following elements must, in order to obtain informed consent, be given particular prominence and be brought to the individual’s attention in a user-friendly format and at an appropriate time:

- The OPC will draft and consult on new guidance that will explicitly describe those instances of collection, use or disclosure of personal information which we believe would be considered inappropriate from the reasonable person standpoint under subsection 5(3) of PIPEDA (no-go zones).

- The OPC will better flesh out the concept of reasonable expectations of individuals in different contexts, including for the purpose of informing the form of consent.

- The OPC will inform individuals of available technological tools designed to implement consumers’ consent choices, and will pursue reports made to us that individuals’ privacy choices have been obstructed.

- The OPC will fund research and knowledge translation activities to promote development and adoption of new consent technologies through our Contributions Program.