Canada Border Services Agency – Scenario Based Targeting of Travelers – National Security

Section 37 of the Privacy Act

Final Report 2017

Executive Summary

What we reviewed

Scenario Based Targeting (SBT) is a component of the Canada Border Services Agency’s (CBSA) National Targeting Program. The objective of the National Targeting Program is to identify people and goods bound for Canada that may pose a threat to the security and safety of the countryFootnote 1 SBT uses algorithms to analyze the Advance Passenger Information/Passenger Name Record (API/PNR) data that is sent to CBSA by commercial air carriers for travelers bound for Canada, using factors such as age, gender, nationality, time spent abroad, travel patterns, and other elements to match individuals against scenarios for further risk assessment. Scenarios are made up of personal characteristics derived from API/PNR, such as age, gender, travel document origin, itinerary and length and pattern of travel.

CBSA uses scenarios to assess travelers for what are considered predictive risk factors in several areas, including immigration fraud, organized and trans-national crime, smuggling of contraband, and terrorism and terrorism-related crimes. Further manual risk assessments are conducted by National Targeting Centre (NTC) officers for individuals who match a scenario. Travelers identified as potentially high risk after CBSA’s risk assessment may be subject to questioning or further examination at the Port of Entry (POE).

Our review focused on scenarios developed for national security assessment purposes only, and included an analysis of the amount and type of personal information CBSA collects as it evaluates individuals identified by scenarios as posing potential risks.

We observed a demonstration of SBT in operation, interviewed selected CBSA NTC officials, and reviewed pertinent policies, processes and standard operating procedure documents. We also analyzed a sample of case files for individuals who were identified as potential risks as a result of matching national security scenario criteria and who were subsequently referred for further examination by a NTC officer. This included Canadians as well as foreign nationals destined for Canada. We examined officer’s notes, database check results, the target report issued by the NTC officer, reports completed by the Border Services Officer (BSO) at the POE as well as records of onward exchanges of personal information to law enforcement and intelligence partners.

We also reviewed national security scenarios, internal CBSA committee meeting minutes related to the SBT initiative, Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with information sharing partners, and CBSA reports on the effectiveness and success rate of national security scenarios.

Why we reviewed Scenario Based Targeting

Approximately 80,000 travelers a day, or 29 million annually, enter Canada in the air mode. Air carriers are obligated under Canadian law to provide CBSA with the detailed personal information of each of these travelers prior to their arrival, so that risk assessments can be carried out.Footnote 2 CBSA loads this data into the Passenger Information System (PAXIS)Footnote 3and uses it to identify individuals whom they suspect are or may be involved with terrorism or terrorism-related crimes, or other serious offences that are transnational in nature. In the past, CBSA used an individual risk scoring method that analyzed specific passengers and gave them a risk value based on their own distinct data elements and travel patterns. Travelers with high risk scores would be flagged for further review.

Scenario Based Targeting uses advanced analytics to evaluate traveler data collected from air carriers against a set of conditions or scenarios, which are composed of the personal characteristics found in API/PNR, such as age, gender and nationality. Individuals whose API/PNR data match a scenario based rule are identified for risk assessment by a NTC officer. As part of the risk assessment process, individuals’ information is automatically shared with U.S. border authorities and they are subject to database and open-source checks. Those who are not cleared of suspicion at initial stages have their information further shared with domestic law enforcement and intelligence agencies. There is a risk that large numbers of individuals who pose no threat to national security may be subjected to recurring attention from CBSA and its law enforcement and intelligence partners, including in other jurisdictions, simply because they fit within the parameters of a scenario.

For obvious security reasons, scenarios are not made public. While this is a necessary precaution, it also means that individuals have no way of knowing that they may match the factors of a scenario and therefore may be subject to increased scrutiny at the border. There is a risk that inaccurate, outdated, or out of context information may be collected and retained by CBSA and its information sharing partners.

What we found

CBSA has implemented policies and procedures to guide the development of scenarios, the risk assessment process for individuals, and the evaluation of scenario effectiveness. The full cycle of SBT activity from the development and activation of scenarios to the identification of targets and the outcomes of further examination is tracked, and there are measures in place to refine scenarios and evaluate their effectiveness. In addition, CBSA recognizes the need to assess scenarios for potential impact on privacy, human rights and civil liberties.

However, there are opportunities for improvement to these processes. While CBSA has processes in place to limit the number of individuals for whom targets are eventually issued, large numbers of travelers – approximately 60,000 a year – are identified by scenarios as potential national security threats at the beginning of the process. All travelers identified as matching a national security scenario are subject to risk assessment queries by NTC officers. These queries involve automatic disclosure of personal information to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the CBSA’s conduct of a variety of other database and open source checks. The personal information of a smaller group of individuals is then further shared with domestic law enforcement and intelligence agencies for purposes of database checks and consultations at subsequent stages of the risk assessment process. Upon receipt and review of this information the NTC officer may refer the individual for further examination at the POE. There is a risk that information disclosed by CBSA for the purposes of database checks may be retained and used by partner institutions for their own purposes, and, in some cases, it may be further shared. The privacy risks associated with these disclosures have not been addressed through the inclusion of appropriate provisions in relevant information sharing agreements, particularly with regard to potential implications for individuals who are cleared of suspicion during the CBSA’s risk assessment.

We noted that CBSA judges the effectiveness and success of national security scenarios against broad outcomes that are not confined to the identification of national security risks, but which also include immigration-related concerns and discovery of contraband. Although we understand the relevance of such statistics to CBSA’s overall mandate, they do not speak specifically to the success of SBT for national security purposes. Further, CBSA measures the success of national security scenarios based on intermediate outcomes such as further investigation on a file, or requests for information being received from partner institutions. Such metrics cannot provide true indication of the success of the SBT program in identifying threats to national security.

We also found that national security scenarios were launched by CBSA during our review period without being formally reviewed for their potential impact on privacy, human rights and civil liberties, despite CBSA’s recognition of these issues and its commitment to undertake such reviews.

Our review determined that, in some cases, CBSA retains more personal information in NTC files and the Integrated Customs Enforcement System (ICES)Footnote 4 than what is necessary for the stated purpose of the program. Additionally, although open source information is not used as a sole determinant of risk, we found that files lack documentation of any steps taken to verify the accuracy and relevance of information collected from social media sites.

What is API/PNR?

Advance Passenger Information (API) and Passenger Name Record (PNR) is traveler data which must, by law, be given to CBSA by air carriers for travelers arriving in Canada. API includes:

- full name

- date of birth

- gender

- citizenship or nationality

- travel document type, number (e.g. passport, visa) and country of issue,

- reservation record locator number

- Passenger reference number

Passenger Name Record data is found in the travel reservation systems used by air carriers and their agents. This information may include:

- ticketing information

- baggage information

- address

- contact phone numbers

- seat number

- payment information

- basic identity data

Background

About the entity

- CBSA was created by Order in Council on December 12, 2003, and falls under the Public Safety Canada portfolio. The Agency’s mandate is set out in the Canada Border Services Agency Act (2005). Footnote 5CBSA provides integrated border services that support national security priorities and facilitate the flow of persons and goods. It is responsible for administering over 90 Acts, regulations and international agreements on behalf of other federal departments and agencies, as well as the provinces and territories. The Customs Act is one of the key pieces of legislation for which CBSA is responsible.

About the Scenario Based Targeting Program

- CBSA is authorized under the Customs Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act to screen travelers entering Canada. The objective of SBT, according to CBSA, is to identify suspected high risk individuals traveling in the air mode. Footnote 6 Under Canadian lawFootnote 7, commercial air carriers are required to provide CBSA with prescribed Advance Passenger Information (API) as well as the Passenger Name Record (PNR) data that they collect for all persons travelling to Canada. Airlines collect API data from passengers before or at check in; PNR is drawn from airline flight reservations systems.

- API includes: name, date of birth, gender, citizenship or nationality and travel document information, and reservation record locator number. With respect to PNR, personal information may include: name, address, traveler's reservation and travel itinerary, which could include point of origin and destination, dates and times of travel.

- Currently, this data must be provided to CBSA an hour before the time of departure for air carrier crew members and no later than the time of departure for travellers expected to be on board. A subsection of the applicable Passenger Information (Customs) Regulations which was not in force at the time of writing requires PNR to be given to CBSA no later than 72 hours in advance of departure.Footnote 8

- Under the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border: A Shared Vision for Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness, Canada committed to implementing a methodology for the screening of all travelers which would harmonize with that of the U.S. Footnote 9As a result, CBSA replaced its previous air traveler risk assessment methodology, which assigned individual risk scores to travelers, and aligned its risk assessment process with that of its American counterpart, the U.S. CBP Automated Targeting System. Footnote 10

- CBSA’s use of API/PNR to perform pre-arrival risk assessments is authorized by section 107 of the Customs Act and section 148(d) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. The Privacy Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms also apply to the activities of the Agency. Fundamental principles such as proportionality and necessity should be observed by CBSA in exercising its statutory requirements.

- National security scenarios are developed from emerging threat information, current intelligence and comparative enforcement analysis. Sources for this information include domestic and international intelligence and law enforcement partners.

- All travelers meeting the criteria of one or more national security scenarios are assessed by a NTC officer. This includes checking for information about the traveler in a number of domestic and international databases, open source searches of social media, and a review of tax records. If the NTC officer determines that the individual may be a risk, a “target” is issued for that traveler, which may result in the traveler being subject to questioning or further examination upon arrival at the POE.

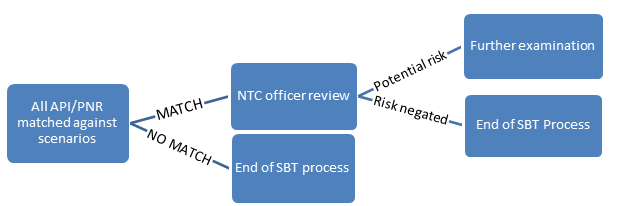

SBT Process

Text version

All Advance Passenger Information/Passenger Name Record (API/PNR) matched against scenarios

- Match

- National Targeting Centre (NTC) officer review

- Potential risk

- Further examination

- Risk negated

- End of Scenario Based Targeting (SBT) Process

- Potential risk

- National Targeting Centre (NTC) officer review

- No match

- End of SBT process

Focus of this review

- Sections 4 through 8 of the Privacy Act limit the collection of personal information by federal government institutions and govern how that information can be used and disclosed. The Act is given effect by central policies, standards, directives, and guidance issued by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), and by policies, processes, operational procedures and information sharing agreements (ISAs) developed by institutions. We examined whether CBSA manages the personal information collected, used, retained, and disclosed under the SBT program in accordance with its obligations under the Privacy Act, applicable TBS policies, directives and guidance, and its own policies, directives and guidelines for personal information management.

- We expected to find that personal information collected under the SBT program:

- Relates directly to the program’s stated purpose;

- Is complete, up to date and as accurate as possible;

- Is used/disclosed only for authorized purposes; and,

- Is managed and disposed of in accordance with governing authorities.

Scope and Approach

- Our examination was limited to national security scenarios. We looked at the files of individuals who were referred for further examination as a result of being identified by a national security scenario during a one year period between January 31, 2016 and January 31, 2017. During this review period, 188 national security scenarios were in operation. According to CBSA, this resulted in the initial assessment of approximately 60,000 travelers and the eventual issuance of 552 national security “targets” for individuals who were referred for further examination. We reviewed a sample of 90 target files from this total.

- We examined the personal information collection practices at the POE as they related to national security targets issued as part of the SBT program. The overall practices of BSOs at the POE and the policies and procedures of other institutions with which traveler information may be shared were not included in the scope of this review. We did not examine the IT infrastructure supporting the SBT program.

Observations and Recommendations

Some information not directly related to the program’s stated purpose is collected and retained.

- Section 4 of the Privacy Act dictates that government institutions shall not collect personal information unless it relates directly to an operating program or activity of the institution.Footnote 11The TBS Directive on Privacy Practices supports the Act by requiring institutions to limit the collection of personal information to what is both directly related to and demonstrably necessary for the institution's programs or activities. Footnote 12

- When an individual arriving in Canada is matched to a national security scenario, additional personal information is collected:

- By NTC officers conducting risk assessments to determine whether to issue a target for an individual to be subject to further examination at the POE, and

- At the POE by BSOs for those individuals referred by the NTC.

- During our sample review of national security scenario target files, we found that CBSA collects and retains personal information that is not directly related to or demonstrably necessary for the objectives of the program. This occurs both at the NTC and at the POE.

- In the 90 NTC files that were reviewed, we found examples of personal information having been collected that did not have any obvious connection to the assessment of national security risks, including information concerning third parties. This included income tax records and social media information for individuals living at the same address as the individual referred for further examination. In approximately a third of case files that we reviewed we found evidence of social media and open source collection. In some of these cases, printouts of entire social media pages including lists of associates, postings, and photos of targets as well as their spouses, children and/or friends had been added to NTC files.

- Subsection 6(2) of the Privacy Act requires government institutions to take all reasonable steps to ensure that personal information used for an administrative purpose is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible. There is a risk that personal information found on social media may be of questionable accuracy and reliability. The files we reviewed containing information collected from social media sites did not include documentation of any steps taken by CBSA to verify the accuracy of that information before it was used and retained.

- The personal information retained as part of the risk assessment conducted by NTC officers includes information collected from the Canada Revenue Agency’s (CRA) Random Access Personal Information Database (RAPID).

- Retention of multiple years of reported income and employer information collected from the CRA RAPID system was observed in a majority of our sample files. This information often included names, birth dates, and other personal information about individuals listed at the same domestic address as the individual being evaluated.

- We reviewed records entered in individuals’ files at the POE for the 90 target files we examined. In approximately a third of the files we reviewed, personal details that did not have any obvious connection to an assessment of national security risk were retained. This included detailed personal information, including medical information about the target and the target’s relatives and associates. For example, in one case, we found a detailed description of an individual’s struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder and the medications being taken for that condition in notes made by the BSO. In addition, the names and phone numbers of third parties found in the targets’ phone contact lists or wallets were recorded in some of the files that we reviewed.

Recommendation:

CBSA should ensure that only the personal information which is directly related to and demonstrably necessary for the purposes of administering the SBT program is collected and retained by NTC and Border Services Officers.

CBSA should document the steps it takes to ensure that personal information used by the SBT program is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible.

CBSA Response:

Agreed. Based on OPC observations and the Agency’s commitment to maintain the highest regard for the privacy of personal information, we will review and modify, as required, internal procedures and related training courses to confirm that only information related to and demonstrably necessary for the program is collected and retained. This update will include a description of the steps to be taken to confirm that the information used is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible.

As part of the Agency’s commitment to the protection of personal information, the CBSA NTC has proactively ceased the notation of CRA transitory information within NTC records as of May 29, 2017.

MOUs with law enforcement and intelligence partners do not sufficiently mitigate all privacy risks related to the personal information that is provided by CBSA for purposes of database checks.

- The TBS Policy on Privacy Protection requires that appropriate privacy protection clauses be included in contracts or agreements involving intergovernmental or trans-border flows of personal information.Footnote 13 Associated TBS guidance recommends that such agreements specify retention periods and methods for destruction of information. Footnote 14

- CBSA discloses personal information about individuals identified by national security scenarios during queries of domestic and international law enforcement and intelligence partner databases. Queries of these databases occur before individuals are referred for further examination at the POE. CBSA automatically queries U.S. CBP for all individuals that match a scenario and may query Canadian public safety partners’ databases if the individual cannot be cleared as a potential risk during preliminary checks. We observed that domestic partner databases were queried in the majority of files that we reviewed.

- As a result of the disclosure of personal information that occurs during these queries, there is a risk that third party law enforcement and intelligence agencies receive and retain the personal information of individuals who are ultimately not considered to be threats to national security by CBSA and for whom targets are never issued. While MOUs require that partner institutions obtain CBSA permission for any onward disclosures, they do not sufficiently address privacy risks associated with those institutions’ retention and internal operational use of the data that is initially disclosed to them by CBSA for the purpose of database checks. TBS guidance on information sharing agreementsFootnote 15indicates that ISAs should identify how personal information shared or exchanged under an agreement is to be used by the recipient organization. Any prohibitions or limitations against subsequent or secondary use of the information should be clearly addressed in ISAs and should take into account the principles of necessity and proportionality.

Recommendation:

CBSA should revise its MOUs with domestic and international partners to ensure they contain specific provisions to limit retention and use of data that is obtained from CBSA for purposes of database checks. Such provisions should mitigate against any ongoing suspicion of people who have been determined to not pose a threat to national security.

CBSA response:

Agreed. The CBSA is already engaged with key domestic partners at differing stages regarding MOU development, and every document will be vetted specifically during the drafting or revision process to ensure the appropriate safeguards are incorporated. Similarly, international partners will be engaged where necessary, to enhance provisions within existing treaties and MOUs to limit the retention and use of data from the CBSA. The CBSA is committed to ensuring that all future international treaties and MOUs include such provisions. As an interim step, the CBSA will undertake an internal scan of key MOUs with a targeted completion date of March 31, 2018.

It is the CBSA’s current practice, as agreements or arrangements are implemented or renewed, to ensure these documents include appropriate privacy protections such as caveats warning against onward disclosure, an obligation to correct information, and to report any privacy breaches involving specific information to the entity that provided the information so that appropriate remedies can be applied. Other provisions may include auditing arrangements between the participants in an arrangement or parties to an agreement.

National security scenarios were launched without first being reviewed for potential privacy, human rights and civil liberties implications.

- An analysis of the privacy impacts of SBT was undertaken by CBSA in 2014 through the conduct of a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA), which was submitted to our office for review. At that time, we recommended that CBSA institute a formal review of scenarios to ensure that privacy, human rights and civil liberties risks are assessed during their development. CBSA agreed to this recommendation in 2016, and made a commitment to undertake formal reviews of scenarios for these concerns.

- The CBSA has a Scenario Management Committee, the purpose of which, according to the Agency, is to conduct ongoing reviews of scenarios as well as scenario development and management to ensure efficiency, consistency and integrity. Scenarios deemed ineffective may be deactivated or modified as a result of this Committee’s work. Oversight is also provided by CBSA’s Targeting Program Management Committee and Program Oversight Team.

- In assessing the progress made by CBSA in implementing PIA-related commitments, we reviewed the minutes and records of discussion for the monthly Scenario Management Committee and Targeting Program Management Committee meetings, as well as for the program oversight quarterly reviews of scenarios. We also interviewed NTC staff members. We found that while SBT program officials regularly discussed scenarios, including their modification and deletion, there was no documented evidence to demonstrate that scenarios were modified or deleted based on privacy, human rights and civil liberties considerations. At the time of our review, CBSA did not have a finalized Standard Operating Procedure to ensure that such reviews occur prior to scenario activation. We found evidence that scenarios had been launched without formal reviews for these considerations.

Recommendation

CBSA should formally review individual national security scenarios for privacy, human rights and civil liberties impacts prior to launch and on an ongoing basis. Decisions made to modify or delete scenarios on the basis of such reviews should be documented.

CBSA response

Agreed. The CBSA will review individual national security scenarios for privacy, human rights and civil liberties impacts prior to launch and on an ongoing basis. All modifications will be documented.

It is the practice of the CBSA Scenario Management Committee to conduct monthly reviews of scenarios for effectiveness, lawfulness and all modifications and deletions are documented. To date, the CBSA has not identified violations of privacy, human rights, and civil liberties within national security scenario based targeting rules.

Privacy impacts will be addressed within the Air Passenger Targeting Privacy Impact Assessment.

Some national security scenarios are broad and the criteria used to assess their effectiveness extend beyond the identification of national security threats.

- Scenarios are continuously monitored and evaluated by CBSA throughout their development and deployment. There are policies in place to govern this process, and several working level committees have been established to discuss scenarios, evaluate effectiveness, and modify factors or delete scenarios where required. In addition, scenarios are subject to other formal and informal quality review processes through which success rates are evaluated.

- While these efforts are notable, some scenarios we reviewed were broad and captured large numbers of travelers. CBSA reports that, of the approximately 80,000 travelers processed each day, approximately 164 individuals are identified daily by SBT as potential national security risks. Annually, this would result in approximately 60,000 individuals being identified by national security scenarios. Of these, a smaller subset is referred for further examination as a result of a target being issued. During the period we reviewed, 552 individuals were referred.

- CBSA reports a high success rate for its national security scenarios, citing a 50.9% result rate for national security targets issued by the NTC and sent for further examination. However, we found that CBSA’s definition of resultant outcomes from national security scenarios was broad and included a variety of CBSA-mandated activities not directly related to the identification of national security threats, such as immigration-related concerns and discovery of contraband. In addition, success measurements employed did not clearly distinguish between intermediate and ultimate outcomes.

- This is a generous interpretation of success in the context of national security, and includes intermediate and therefore inconclusive outcomes as measures of success. Given that the SBT program is not confined to only the identification of national security threats, we understand CBSA’s desire to note all outcomes. However, without specifically aligning some of its measurement criteria to confirmed national security outcomes, CBSA cannot demonstrate that the personal information collected for purposes of the SBT program is necessary and proportionate for national security risk assessment purposes.

Recommendation

CBSA should continue its efforts to refine existing processes for review and modification of national security scenarios to ensure scenario factors are carefully tailored to limit the collection of personal information, minimize intrusiveness and ensure proportionality.

The criteria for measuring the success of national security scenarios should include some measurements that specifically align to national security related outcomes and be based on the ultimate outcome of the target, rather than on interim results.

CBSA response

Agreed. The CBSA will continue to review and refine national security scenarios in order to limit the collection of personal information, minimize intrusiveness, and ensure proportionality.

CBSA’s risk assessment is an incremental and multi-layered process, which begins with an initial risk assessment of all arriving commercial air passengers. The extent of personal information collected during this process increases at each step and is proportionate to our need to detect and prevent terrorism or serious transnational crimes. SBT is a method that is minimally invasive in terms of privacy impacts, which allows the CBSA to achieve its national security and public safety mandate.

SBT ensures that only a finite number of travellers are selected for further risk assessment and of those, only a limited number are referred for further examination at a port of entry.

In 2016-17, of the approximate 29 million travellers who arrived in Canada by commercial air carrier:

- approximately 60,000 or 0.2% of travellers matched a national security SBT rule;

- Of the 60,000 travellers, 552 were identified for further examination at a port of entry based on risk assessments by an NTC targeting officer, which represents 0.002% of the 29 million travellers.

The CBSA does not keep an active record of all persons who matched a SBT rule and were subsequently deemed to be of low risk. The CBSA only retains a record of those individuals for whom a request for examination at the port of entry was issued. This record is retained for an activation period of seven days, is subsequently deactivated for access by all frontline personnel and is retained only for the purposes of file management, recording of examination results, and risk determination.

In regards to measuring success, the targeting program reports on both direct and indirect results achieved in the conduct of an examination at the POE.

All examination reports are reviewed for results from a customs, immigration, and intelligence perspective. Analysis of these results enables the CBSA to continuously modify and/or delete national security SBT rules to further improve results and further facilitate entry of low risk travellers.

Going forward, the CBSA will continue to capture both indirect and direct results of all referrals and examinations, including measures which are aligned to national security related outcomes.

Conclusion

- CBSA collects and retains some information that is not directly related to the purpose and objectives of the SBT program, and should take further steps to prevent the over-collection of personal information.

- CBSA’s information sharing agreements with its partners do not mitigate risks associated with the disclosure of information by CBSA for scenario-identified travelers during database checks. Agreements should be amended to ensure they contain specific provisions to limit retention and use of data that is obtained from CBSA for purposes of database checks, in order to mitigate against any ongoing suspicion of individuals who have been determined to not pose a threat to national security.

- National security scenarios are not formally reviewed for potential privacy, human rights and civil liberties impacts prior to their launch. CBSA should address this by undertaking formal reviews prior to the launch of national security scenarios. Decisions made to implement, modify or delete scenarios based on those reviews should be documented.

- Some of CBSA’s metrics for assessing the success and effectiveness of SBT national security scenarios should be specifically aligned to confirmed national security outcomes, to ensure necessity and proportionality and that the privacy intrusiveness of the program can be appropriately evaluated against national security outcomes on an ongoing basis.

- We recognize the importance of a program for assessing the potential risk of individuals arriving in Canada for national security threats. CBSA has the legislative authority to assess travelers arriving in Canada for risks, and to refer individuals for further examination based on risk indicators, or indeed, at random. CBSA has developed policies and procedures to govern personal information management for the SBT program, including regular review of scenarios for effectiveness.

- However, we are concerned that some scenarios used for this purpose in the national security context are broad, and are based on API/PNR data that includes personal characteristics which by their nature identify a large number of law abiding individuals. This creates a risk that personal information that is not directly related to or necessary for the SBT program’s administration is being collected, used, retained and shared.

- Although we understand that the application of scenarios to passenger information is the first step in the process and that subsequent analysis results in a smaller sub-set of individuals being referred for further examination, we remain concerned that approximately 60,000 travelers a year are being identified as potential security threats. Their personal information is being collected, assessed and shared with other agencies, including a foreign partner. CBSA should more carefully tailor its national security scenarios, in light of the increased scrutiny and invasion of privacy that results for those individuals who match a scenario, particularly given that the vast majority are ultimately found to pose no national security threat.

- It is important that CBSA handles the personal information collected about individuals through the SBT program in a privacy-sensitive manner which recognizes the potential negative repercussions for innocent individuals who, despite posing no actual threat to national security, may be impacted by such broad-based assessment efforts. Assessing the potential risk associated with all travelers arriving in Canada, however crucial a function, is inherently privacy invasive, particularly when it is based on API/PNR data which can include sensitive personal information. In our view, risks to privacy can be mitigated through measures such as minimizing the data being collected, used, and retained to that which is demonstrably necessary for the assessment of national security threats, ensuring information sharing agreements with partners provide explicit protection for the personal information being shared, reviewing national security scenarios for privacy, human rights and civil liberties implications, and employing success measurements that are specifically aligned with articulated program goals.

About the Review

Authority

Section 37 of the Privacy Act empowers the Privacy Commissioner to undertake compliance reviews of the personal information management practices of federal entities listed in the Schedule to the Act.

Objectives

To assess whether there are adequate controls—including policies and procedures—to ensure that personal information handling practices under the SBT program are in compliance with the Privacy Act.

Scope

The examination of SBT related activities covered a one-year period (January 31, 2016 to January 31, 2017). We examined the SBT program from the development and application of national security scenarios to the outcome for individuals identified through this methodology. This included examination of data accessed to facilitate target identification, records prepared by targeting officials, reports issued to Border Services Officers, and reports on the outcomes of examinations undertaken by BSOs. The review focused exclusively on national security scenarios, and did not include an examination of the IT infrastructure that supports the SBT program. The review was substantially completed by March 31, 2017.

Criteria

The criteria for conducting reviews are derived from sections 4 to 8 of the Privacy Act and associated Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) policies, directives, standards and guidelines that relate to the management and protection of personal information.

The review assessed whether the CBSA is meeting its obligations under the Privacy Act and TBS policies, directives, standards and guidelines in regard to the personal information collected as part of the SBT program. To that end, inquiries were made to determine whether CBSA has ensured that personal information collected, used and retained under the SBT program:

- Relates directly to that program’s stated purpose;

- Has been determined by the CBSA to be as complete, up to date and accurate as possible;

- Is used and/or disclosed only for authorized purposes; and,

- Is managed and disposed of in accordance with governing authorities.

Standards

The review was conducted in accordance with the legislative mandate, policies and practices of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, and followed the spirit of the audit standards recommended by Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada.

- Date modified: