OPC’s Guide to the Privacy Impact Assessment Process

Federal institutions can now use the new online PIA submission form to send PIAs and related documents to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

Once you have completed your PIA, go to Submit a PIA to access the online submission form.

Section 1 – Purpose

This document provides guidance to federal public sector institutions on how to comply with the Privacy Act and effectively manage privacy risks as part of the privacy impact assessment (PIA) process. It presents key concepts and lays out how an institution may assess its programs and activities, including the legal requirements and privacy principles to consider.

It also clarifies the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s (OPC) role in the PIA process and sets out our expectations of government institutions with respect to the PIAs we receive.

Section 2 – Context

In the digital age, it has become far easier to collect, store, analyze, and share huge amounts of personal information. Many Canadians have become accustomed to living and working in connected, online networks. And digitization has created new opportunities for organizations to more efficiently accomplish their tasks. As the privacy landscape continues to evolve, the Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada (TBS) policy suite, of which the Directive on Privacy Practices and the associated Standard on Privacy Impact Assessments are a part, will also evolve. The increasing emphasis on information sharing, data strategies, and the use of new technologies such as artificial intelligence will continue to change the way government works.

Government institutions hold much more personal information today than when the Privacy Act became law in 1983. And while more extensive and innovative uses of personal information may bring greater economic and social benefits, this also increases potential privacy risks.

Individual privacy is not a right we can simply trade away for innovation, efficiency or commercial gain. Canadians agree. An overwhelming majority – 93% – say they are concerned about their privacyFootnote 1, which suggests that having good privacy practices is not just a legal requirement, it is essential to ensuring public trust in our institutions.

We know it is not always easy. Indeed, it has become harder than ever to know for certain whether information held by a government institution could be used to identify an individual when combined with other information – for example, when combined with information available on the Internet or with information held by another government institution or a third party. This means that more information may qualify for protection as “personal information,” even though it does not directly identify an individual on its own.

In today’s environment, assessing potential privacy risks is more important than ever.

While PIAs are currently a requirement of a TBS directive, we have recommended to Parliament that the Privacy Act be amended to require government institutions to:

- conduct PIAs for new or significantly amended programs involving personal information

- submit their PIA reports to the OPC before implementing a program or activity

Done properly and before launching an initiative, PIAs can help ensure that legal requirements are met and that privacy impacts are either addressed or minimized, before a problem occurs. In other parts of the world such as Europe, PIAs are becoming the legal standard.

Section 3 – Role of the OPC

The Government Advisory Directorate

The OPC’s Government Advisory (GA) Directorate provides advice to federal public sector institutions on specific programs and activities involving personal information. We provide advice through:

- consultation

- reviewing PIA reports, information sharing agreements, and notifications under s. 8(2)(m) and s. 9(4) of the Privacy Act

- conducting advisory engagements

Consultation service and report review

The OPC is pleased to offer early consultation on PIAs. However, institutions don’t need a PIA to engage with us on privacy issues. The OPC can provide federal institutions with more informal, proactive advice and guidance on programs and activities that may impact privacy.

As per the Directive on Privacy Practices, institutions must provide their completed PIA reports to the OPC at the same time they provide them to TBS. However, we encourage you to consult us long before you finalize your report. The OPC is happy to engage in informal discussions and to answer questions and provide advice to institutions early in the development and throughout the lifecycle of their programs and activities.

Tip: Don’t hesitate to contact the Government Advisory team at the OPC at any stage for assistance in identifying compliance issues as well as risks to privacy and potential mitigation strategies.

Once the PIA report is completed, we review the final version, and provide written recommendations where we identify additional risks or gaps. The OPC does not approve, endorse or sign off on PIA reports or on government programs or activities.

The OPC reviews all PIA reports we receive. However, we use a triage process to determine which reports will be subject to a secondary review and formal recommendations.

Our triage process takes into consideration factors such as:

- the sensitivity of the personal information

- the number of people affected

- whether there is parliamentary or public interest in the topic

- whether a novel technology is used

- whether the initiative relates to one of the OPC’s strategic priorities

You should submit select relevant documents, such as information-sharing agreements and summaries of security assessments to the OPC with your PIA report. We may request supplementary documents, in-person meetings or site visits, where needed. The OPC is happy to provide advice and answer questions before and during the PIA process.

Notwithstanding the role of the OPC in the review of PIA reports, accountability for privacy compliance rests squarely with the heads of federal institutions or the official responsible for section 10 of the Privacy Act.

Tip: The OPC may comment publicly, including in our annual report to Parliament, on advice we have provided to institutions regarding the privacy risks posed by their programs and activities, including whether that advice was accepted.

How to reach the OPC’s Government Advisory Directorate

- By email: scg-ga@priv.gc.ca

- By mail:

Director, Government Advisory Directorate

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec

K1A 1H3

Section 4 – Privacy impact assessments

It is critical that you determine the legal authority for your program or activity before considering whether you should undertake a PIA. If you do not have legal authority, you should not proceed with the initiative. The advice and direction provided in this document assume you have legal authority to collect, use and disclose information as part of your project.

What is a PIA and what is its purpose?

A PIA is a risk management process that helps institutions ensure they meet legislative requirements and identify the impacts their programs and activities will have on individuals’ privacy.

First and foremost, conducting a PIA is a means of helping to ensure compliance with:

- legal requirements set out in the Privacy Act

- the institution or program’s enabling legislation

- the requirements of TBS and Government of Canada policies and directives

Adhering to the requirements above will reduce your risk of improper or unauthorized collection, use, disclosure, retention or disposal of personal information.

While programs and activities must comply with legal and policy requirements, they should also be designed to incorporate best practices and to minimize negative impacts on the privacy of individuals. For example, you should work to reduce the risk that an individual may suffer harm, such as identity theft, reputational damage, physical harm or distress, as a result of your program’s handling of their personal information. A PIA may not eliminate such risks altogether, but should help to identify and manage them. There is often more than one way of designing a project. A PIA can help identify the least privacy intrusive way of achieving a legitimate aim.

PIAs are an early warning system, allowing institutions to identify and mitigate risks as early and as completely as possible. They are a key tool for decision-makers, enabling them to deal with issues internally and proactively rather than waiting for complaints, external intervention or bad press.

An effective PIA can help build trust with Canadians by demonstrating due diligence and compliance with legal and policy requirements as well as privacy best practices.

A PIA report documents the PIA process. The real value comes from the analysis that occurs as part of the process of working through the PIA questions.

Tip: Institutions should ensure compliance with the Privacy Act. Even when a program is legally compliant, you should identify and manage the risk that it may negatively impact the privacy of individuals. Where possible eliminate impacts altogether.

What a PIA is not:

- a superficial legal checklist

- a one-time exercise

- a marketing tool that only shows the benefits of a project

- a justification for policies already decided, or practices already in place

- necessarily long, complicated and resource-intensive

When is a PIA required?

PIAs are required under the TBS Directive on Privacy Practices and have been a policy requirement since 2002. In 2024, TBS updated the policy instruments associated with PIAs and introduced a mandatory standardized PIA template.

A PIA is generally required if your program or activity may have an impact on the personal information of individuals. The TBS Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment requires that institutions conduct PIAs:

- when personal information may be used as part of a decision-making process that directly affects the individual

- when there are major changes to existing programs or activities where personal information may be used for an administrative purpose (meaning as part of a decision-making process that directly affects the individual). Major changes might include the use of a new or modified information technology, the involvement of another institution or third party under contract or other agreement, and the use of an automated decision system that would require compliance with the TBS Directive on Automated Decision-making.

- when there are major changes to existing programs or activities as a result of contracting out or transferring programs or activities to another level of government or to the private sector

The Privacy Act defines personal information as “information about an identifiable individual that is recorded in any form”. Examples of personal information include: name, address, employment history, fingerprints, medical diagnoses and personal opinions.

Examples of administrative uses of personal information include using personal information:

- to decide whether an individual can enter the country

- to determine whether an individual is eligible to receive a social service

- to investigate an individual for possible wrongdoing

You may decide to conduct a PIA for your institution’s new or substantially changed programs or activities even if no decisions are made about individuals. The TBS Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment encourages institutions to undertake a PIA if their program or activity will have an impact on privacy and there are potential privacy risks that should be assessed and mitigated. While you may not be required to do a PIA in such circumstances, thoroughly assessing risks to privacy through a PIA will help you develop legally compliant and privacy-friendly programs.

If your program or activity uses personal information for a non-administrative purpose, such as research or statistical monitoring, the Directive on Privacy Practices now requires federal institutions to prepare a privacy protocol. A privacy protocol is a set of documented procedures that explain how you will handle personal information in a manner that is consistent with the Privacy Act.

Use the Preliminary Risk Assessment section found later in this document to help you determine your program or activity’s potential privacy impacts and to get a sense of the risk level. Based on this assessment you may choose to conduct a PIA even when there is no administrative use of personal information. Institutions should consider each project individually to decide whether a PIA is warranted.

Tip: It is important to assess the privacy impacts of new as well as old initiatives. The Directive on Privacy Practices requires institutions to conduct PIAs for existing projects, even those that may predate the TBS PIA requirement. Begin with programs and activities likely to pose the greatest risk.

Text version of Figure 1

Use this flowchart to help you determine if you need to do a PIA

- START

- Does the program or activity involve personal information?

- If no: A PIA is likely not required.

- If yes: Is personal information used as part of a decision-making process that directly affects an individual?

- If no: Will the program or activity have an impact on privacy and should potential privacy risks be assessed and mitigated?

- If no: A PIA is likely not required.

- If yes: Conduct a PIA.

- If yes: Is there already a PIA for this program or activity?

- If no: Conduct a PIA.

- If yes: Has anything changed?

- If no: Updating the PIA is likely not required.

- If yes: Update the PIA.

- If no: Will the program or activity have an impact on privacy and should potential privacy risks be assessed and mitigated?

Documenting the decision

If you decide not to conduct a PIA, document your decision and the rationale. As a best practice, you should identify and address the privacy impacts of your programs and activities even when you do not do a formal PIA.

Other assessments and procedures

Consider whether you should complete other formal assessments or procedures along with or instead of a PIA.

Whereas PIAs concentrate on privacy compliance as well as risks to privacy posed by programs and activities, other assessments have different areas of focus. For example:

- Security assessments and authorizations evaluate security practices and controls to establish the extent to which they are implemented correctly, are achieving the desired outcome and whether related residual risk should be accepted

- Business impact assessments identify and prioritize a department’s critical services and assets to allow for selection of suitable measures to address risks to the availability of those services and assets

- Algorithmic impact assessments identify and mitigate risks associated with deploying an automated decision-making system.Footnote 2

Consult TBS’s policy suite to determine whether other assessments or procedures may be required.

Tip: If the types of questions posed in the Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment and the standard PIA template or in this guide seem ill-suited to your project, perhaps a PIA is not the assessment you should be doing! You can always contact our office to discuss your concerns.

What should a PIA include?

The TBS Standard PIA Template sets out content that must be included in PIA reports. You must follow the template and consult the Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment to ensure that your PIA complies. You are encouraged to include any additional information that you feel is relevant to your assessment to complement the information provided for within the template.

In general, your PIA report should include:

- a description of the planned program or activity and its objectives

- an assessment of your program’s privacy compliance as well as its potential impacts on individuals’ privacy

- the measures planned to minimize impacts and to comply with the Privacy Act, applicable TBS policies, directives and guidelines as well as best practices

Beyond TBS requirements, this document outlines the Privacy Act requirements and best practices that institutions should consider in going through the PIA process. The discussion that follows is intended to help institutions comprehensively assess and reduce risks to privacy. Whether you follow the steps in this guide or not, it is our office’s expectation that you meaningfully analyze the privacy impacts of your initiatives.

The process is designed to be flexible and scalable. The length and complexity of your PIA process will depend on the scale, complexity and risk level of your project.

How to do a PIA

Key takeaway: Don’t be intimidated! PIAs are a tool to help you assess the privacy impacts of your program and to identify any compliance issues. If you know your program you can conduct a PIA.

Planning phase

Determine your legal authority for the program or activity.

Prioritize.

- Begin with programs and activities likely to pose the greatest risk

Start early.

- Start your PIA before undertaking new or substantially changed programs or activities, in all but exceptional cases

- You should begin the PIA process early enough in the development of your project so that it is still possible to influence the project design

- For example, if there are significant negative privacy impacts, you may want to reconsider your approach to the project

- It is best to identify, reduce, and mitigate privacy impacts before they occur, as opposed to finding remedies after the fact

- Remember, your PIA report can be an evolving document that you build as project details become clear

- You should analyze privacy impacts throughout your program or activity. The PIA is a tool to guide and document this analysis

- Gather any published information, business case documents, existing assessments, analysis or legal advice about your project and about privacy in your institution more generally

- Collect current or draft technical specifications or system designs to aid in the PIA process

- Where possible, contact other institutions that operate similar initiatives on which they may have conducted PIAs

- Use your PIA to support a Privacy by Design approach and help ensure that privacy is an essential component of the program or activity being delivered

Scope appropriately to ensure areas impacting privacy rights are covered.

- Consider what the PIA will cover, how detailed it needs to be and what areas are outside the scope

- Ensure your PIA report clearly describes what is and is not being assessed and covers all aspects of the initiative that may impact privacy

- Based on your scope, estimate how long you will need to complete your PIA and the budget and other resources required

Tip: Scope your project well

- At the OPC, we have seen PIAs scoped at the program architecture level so that very limited detail is included on individual programs or activities and their risks. Such PIAs are scoped too broadly!

- We have also seen PIAs scoped at the program or activity level where half of the program or activity (sometimes the riskier or more controversial part) was considered out of scope. These PIAs are scoped too narrowly!

Involve the right people.

- Which stakeholders will you need to consult?

- When and how should they be involved?

- Who will ultimately draft the PIA?

- Who will be responsible and accountable for ensuring recommendations are implemented?

Key parties may include:

- Program staff (that is, the person or people responsible for developing and delivering the program or activity)

- Privacy staff, including your Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) group and your Chief Privacy Officer, where one exists

- Internal legal counsel

- Information Management (IM), information technology (IT) and security, as required

- Front-line staff, as required

- Private-sector third parties, if involved in the program or activity

- The senior official or executive responsible within the institution for new or substantially changed programs or activities (as per the Directive on Privacy Practices)

- Heads of government institutions or the official responsible for section 10 of the Privacy Act (as per the Directive on Privacy Practices)

You may not need to engage all of the parties listed above for each PIA, however, at a minimum, involve relevant program and privacy staff in any PIA process.

Tip: If a consultant is conducting your PIA, ensure you have capacity within your institution to implement recommendations and engage with the OPC once their contract is over.

Multi-institutional PIAs:

- Where two or more institutions intend to establish a common initiative or to share information, it may be economical and desirable to conduct a multi-institutional PIA

- These overarching PIAs help to paint a complete picture of a program or activity that may not otherwise be clear

- When different institutions do separate PIAs on small components of a shared project it can be harder to see the big picture

- Multi-institutional PIAs help to reduce the chances of gaps or inconsistencies

- Multi-institutional PIA reports should clearly set out which party is responsible for addressing risks. Always appoint a lead institution with overall responsibility for the PIA

Tip: Ideally, institutions will conduct one multi-institutional PIA where they are involved in delivering a shared program or activity. Where institutions do not conduct multi-institutional PIAs, they should, at minimum, work closely with program partners to develop separate PIAs that are clearly scoped.

Consult the OPC

- The OPC’s GA Directorate provides advice to institutions related to specific programs and activities involving personal information, including throughout the PIA process

- For more information, see Section 3 – Role of the OPC

- Under TBS policy, institutions are required to contact our office to discuss any new or existing programs or activities that could impact privacy – whether or not a PIA is planned

At the end of the planning phase you should have identified the scope of the PIA, the resources needed, the individuals who will be involved, and the timeframe for the process.

The PIA Process

Text version of Figure 2

- Confirm the need for a PIA

- Plan

- Consult (include OPC)

- Assess necessity and proportionality

- Identify and assess specific risks

- Create measures to mitigate

- Get approval

- Report to TBS and OPC

- Monitor continuously

Risk analysis phase

All of your institution’s activities involve some kind of risk. Institutions manage risk by identifying it, analyzing it and then evaluating whether the risk needs to be mitigated.

Analyzing risk can help you make choices when the options involve different types and levels of risk. It also gives you the chance to identify the most serious and the most likely problems. For each risk, two calculations are required:

- the likelihood of the incident occurring

- the extent of the impact on privacy rights or harm, if it occurs

A PIA’s focus is on risk to privacy – that is, risk posed to the individual’s privacy and rights under the Privacy Act. It is not a general risk assessment. Therefore, your analysis of a risk’s impacts should consider the type of harm that an individual might experience if the risk occurs. For example, is the individual’s reputation, financial status or emotional well-being at risk?

The likelihood of the risk occurring can range from almost certain (the event occurs regularly) to rare (the event almost never happens).

Where you have determined that your program or activity may negatively impact an individual’s privacy, there is also a risk that your institution is not complying with its obligations under the Privacy Act. Address legal non-compliance immediately.

Tip: Even small amounts of personal information, handled inappropriately, can impact someone’s privacy in ways that you did not intend.

Tip: Use visual aids, such as flow charts, to document how you will use information as part of a project to help you identify privacy risks.

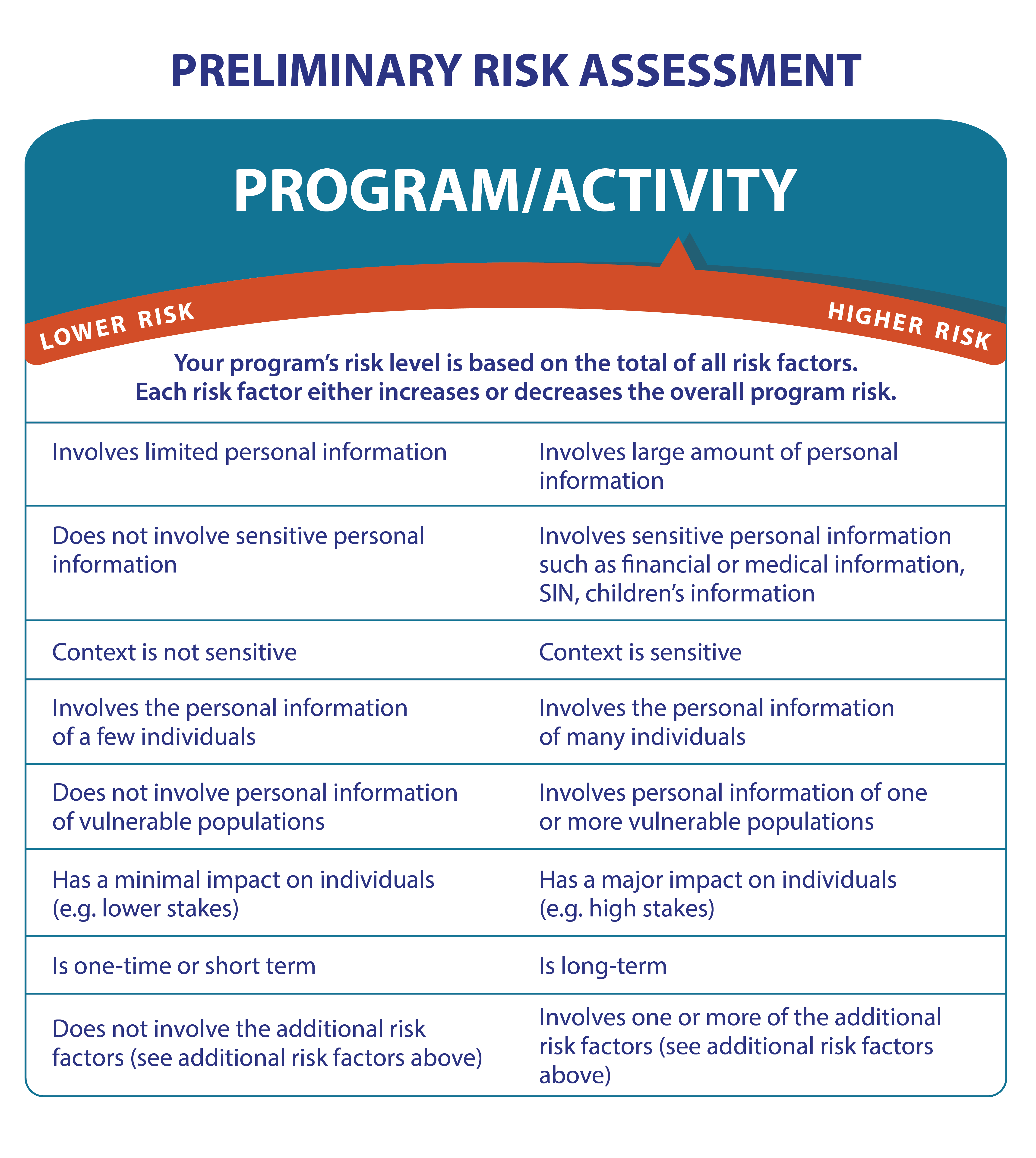

Preliminary risk assessment

When assessing the privacy impacts of your program or activity, it is a good idea to do a preliminary risk assessment. This will help you determine your program or activity’s potential privacy impacts and give you a sense of the risk level. The more privacy risk associated with your program or activity, the more you will need to analyze and mitigate the risk.

Risk factors

When doing a preliminary assessment consider the following risk factors:

- amount of personal information involved

- sensitivity of the personal information involved

- sensitivity of the context in which the program or activity will operate

- size of the population impacted

- whether the affected population is a vulnerable population

- type of potential impact on individuals

- duration, or permanence, of the program or activity

- whether the program or activity involves the following additional risk factors:

- using personal information for secondary purposes

- sharing personal information outside of the institution

- profiling or behavioural predictions

- automated decision-making

- systemic monitoring of individuals

- collecting personal information without notice to or consent of the individual

- data matching (linking unconnected personal information)

Tip: You should consider how your initiative might impact the privacy rights of different groups. For example, you can use Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives from a privacy perspective.

Text version of Figure 4

Preliminary risk assessment

| Your program’s risk level is based on the total of all risk factors. Each risk factor either increases or decreases the overall program risk. | |

| Lower risk | Higher risk |

|---|---|

| Involves limited personal information. | Involves large amount of personal information. |

| Does not involve sensitive personal information. | Involves sensitive personal information such as financial or medical information, SIN, children’s information. |

| Context is not sensitive. | Context is sensitive. |

| Involves the personal information of a few individuals. | Involves the personal information of many individuals. |

| Does not involve personal information of vulnerable populations. | Involves personal information of one or more vulnerable populations. |

| Has a minimal impact on individuals (e.g. lower stakes). | Has a major impact on individuals (e.g. high stakes). |

| Is one-time or short-term. | Is long-term. |

| Does not involve the additional risk factors (see additional risk factors above). | Involves one or more of the additional risk factors (see additional risk factors above). |

Low-complexity, low-risk programs

As previously mentioned, the PIA process is designed to be flexible and scalable. The length and complexity of your PIA process will depend on the scale, complexity and risk level of your project. If, based on the materials you have gathered and your preliminary risk assessment, you have determined that your initiative is simple and low risk, you may accordingly conduct a simple PIA with a brief report.

Even a PIA on a low-complexity, low-risk initiative should address all key components in sufficient detail, but you may find that:

- fewer parties need to be involved in the process

- stakeholder consultation may not be necessary

- there are limited information flows to map

- there are fewer components to describe

- there are fewer privacy impacts and therefore fewer recommendations to discuss

- the final report is shorter

By consulting with our office early in the process, we can provide guidance on how to conduct an appropriate PIA.

Questions for high-risk programs: necessity, effectiveness, proportionality and minimal intrusiveness

Implementation of privacy intrusive government programs has underlined the importance of ensuring that the broader privacy risks and societal implications of some initiatives are carefully evaluated at the outset. You should assess high-risk or privacy-invasive programs or activities in the context of their potential impact on our right to privacy. This assessment should include asking probing questions about the need for the program and whether its impacts are in proportion to its purported benefits. Ask these questions early in the PIA process and not as an afterthought once your program or activity is already developed.

If, based on your preliminary risk assessment, you have identified your program or activity as high risk, you should:

- demonstrate that your institution’s privacy-invasive programs or activities are necessary to meet a specific need

- consider whether they are rationally connected to a public goal that is pressing or substantial and explain this clearly and specifically

- don’t simply reiterate the institutional mandate, for example, "law enforcement" or "border control”

- once the necessity of the initiative has been established, consider the need for each element of personal information being collected

- is each piece or category of personal information necessary to achieve the goal?

- ensure that the proposed program or initiative is likely to be effective in meeting the pressing and substantial goal

- was it carefully designed to achieve the objective in question?

- assess whether your institution’s intrusion on privacy caused by the program or activity is proportional to the benefit gained

- the more severe the impact on privacy, the more pressing and substantial the public goal should be

- consider whether there is a less privacy intrusive way of achieving the same end

- have evidence that supports your argument for using privacy intrusive or invasive activities or technologies

- is there empirical evidence in support of the initiative?

- can your institution demonstrate that these measures are effective in meeting stated needs?

- is there empirical evidence that other, less privacy intrusive means will not achieve the objectives of the initiative?

If your institution cannot explain how your initiative’s proposed collection, use or disclosure of personal information is rationally connected to a pressing and substantial public goal, the initiative should not go forward. In this case, the institution should review the initiative’s objectives and revisit whether it indeed has the legal authority to proceed. You should demonstrate that your high-risk program or activity is necessary, effective, proportional and minimally intrusive before proceeding with implementation.

Tip: While the questions discussed above are necessary for assessing a high-risk initiative, they are useful questions to ask when beginning any project and can help to ensure that key privacy considerations are taken into account at the design stage.

Text version of Figure 5

Roadmap for high-risk programs

If, based on your preliminary assessment, you have determined that your program or activity is high risk, follow the roadmap below.

Step 1. Consider the impacts of your program on our right to privacy and other fundamental rights and values at the earliest stage possible in program development

Step 2. Ask key questions to evaluate the necessity, effectiveness, proportionality and minimal intrusiveness of your initiative

Step 3. Document your rationale for proceeding with privacy intrusive or invasive activities or technologies and use empirical evidence to support your argument

Step 4. Ensure high-risk programs or activities are necessary, effective, proportional and minimally intrusive before proceeding with their implementation

Risk analysis by privacy principle

If you are developing a project that involves personal information, you must comply with the Privacy Act. Your PIA should clearly demonstrate how your initiative meets legal requirements as well as the policy requirements of the Government of Canada. After ensuring your compliance with law and policy, you should then work to further minimize your initiative’s intrusiveness.

As you analyze risks to the privacy of individuals and propose mitigating measures, we recommend that you assess your program against the principles below. They are based upon the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, which have shaped and largely underpin privacy and data protection legislation around the world. They are meant to provide a useful framework for your analysis. For each principle, determine whether your project complies with the relevant Privacy Act provision and policy requirements, then identify any negative impacts on privacy as well as mitigations. Depending on the nature of your initiative, you may consider some principles in more depth than others. The lists under each principle are also not exhaustive. You may have other questions or measures for your institution. Again, it is our office’s expectation that you meaningfully analyze the privacy impacts of your initiative.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): The OECD is a forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. For several decades, the OECD has been playing an important role in promoting respect for privacy as a fundamental value and a condition for the free flow of personal data across borders. In 1980, the OECD introduced the Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, the first internationally agreed upon set of privacy principles. As an OECD member, Canada has committed to implementing the principles domestically to ensure the protection of privacy and individual liberties in respect of personal data.

For more information, see the OECD Privacy Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data.

Accountability

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 3.1

Relevant policy requirements: Policy on Privacy Protection and Directive on Privacy Practices

What “accountability” means: Put someone in charge of your institution’s handling of personal information and develop privacy policies, procedures and training.

Questions to consider:

- Who is responsible for your institution’s compliance with the Privacy Act and privacy best practices?

- What policies and procedures does your institution have in place to protect privacy?

- What policies and procedures do you have in place to protect privacy as part of this specific initiative?

- How do you ensure staff receive privacy training?

- What tools are in place to monitor employees who are involved in managing personal information?

- What is the process for receiving, assessing and responding to privacy complaints and inquiries?

Risk examples:

- Individuals may not know who to contact about privacy questions or concerns

- Staff may be uninformed about how to protect privacy

- Privacy issues may not be identified and shared with the person accountable for compliance with the Privacy Act

Mitigation examples:

- Make the identity of the individual accountable for your institution’s personal information handling practices known

- Develop and implement personal information-handling policies and procedures for your institution and for specific initiatives, as appropriate

- Train staff and communicate information to staff about the institution’s policies and practices

- Monitor your institution’s handling of personal information

- Develop a process for receiving, assessing and responding to privacy complaints and inquiries

Limiting collection

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 4

Relevant policy requirements: Directive on Privacy Practices and Directive on Social Insurance Number

What “limiting collection” means: Only collect personal information if it is directly relevant to your initiative and needed to meet its objectives.

Questions to consider:

- Why do you need to collect this piece or category of personal information?

- Is the information a genuine “need to have” or a “nice to have”?

- Are there specific laws or regulations that allow you to collect the information?

Risk examples:

- An individual’s personal information could be collected when it is not related to or necessary for a program or activity

- Personal information could be collected without a clear purpose

Mitigation examples:

- Have a clear purpose for collection and collect only that personal information necessary for the stated purpose

- Use information that will not identify individuals, where possible

- Design forms and systems so that only the information required is likely to be collected

- Make a clear distinction between mandatory and optional information

- Conduct a data minimization exercise to question the need for each piece or category of personal information

- Where over-collection occurs, appropriately dispose of or return personal information as soon as possible

Tip: Even personal information that is publicly available should only be collected where it relates directly to an institution’s operating program or activity.

Direct collection and purpose identification

Relevant legal requirements: Privacy Act s. 5(1), (2) and (3)

Relevant policy requirement: Directive on Privacy Practices

What “direct collection” and “purpose identification” means: When you collect someone’s personal information, collect it directly from them whenever possible and tell them why you need it.

Questions to consider:

- From whom will an individual’s personal information be collected?

- If you are collecting an individual’s personal information from other individuals or sources, why?

- How is the individual informed of the purpose for collection of their personal information?

Risk examples:

- Individuals may be unaware of the collection, and subsequent use and disclosure of their personal information

- Information collected from other sources may be inaccurate, out of date or incomplete

- Individuals will not be able to update their information if they are not aware it has been collected

- Personal information could be collected without a clear purpose

Mitigation Examples:

- Ensure you collect personal information from reliable sources

- Notify individuals of the purpose for collecting, using and disclosing their personal information

- Whenever possible, notify individuals at or before the time of collection

- Establish a process for responding to requests to amend or correct personal information

- Notify individuals of the procedures for correcting their personal information

Retention

Relevant legal requirements: Privacy Act s. 6(1) and Privacy Regulations s. 4(1) and (2)

Relevant policy requirements and other references: Directive on Privacy Practices and OPC Guide on Personal information retention and disposal: Principles and best practices

What “retention” means: Only keep personal information for as long as you need it.

Questions to consider:

- For how long do you need to keep the personal information?

- Is there legal, regulatory or policy authority for retaining the information?

- How are you made aware when information has reached the end of its retention period?

- In what form and format will information be retained?

Risk examples:

- Personal information is retained longer than necessary for “just in case” scenarios

- Personal information is not retained long enough to allow individuals to obtain access

- Personal information retained for long periods may become inaccurate or out-of-date

Mitigation examples:

- Establish minimum and maximum retention periods

- Have in place a records disposition authority (RDA) or appropriate interim measure

- De-identify retained information, where appropriate

- Limit access to personal information that must be retained, but is no longer being used

- Configure systems to delete personal information once the retention period has been reached or to flag it for review

- Conduct periodic audits or spot-checks of your holdings to ensure personal information is not being retained beyond established time periods

Tip: Keeping information longer than necessary may increase the risk and exposure of potential data breaches.

Tip: In assessing what is the appropriate retention period and whether it is time to dispose of personal information, an institution should consider the following points:

- Reviewing the purpose for having collected the personal information in the first place is generally helpful in assessing how long certain personal information should be retained

- If personal information was used to make a decision about an individual, retain it for the legally required period of time thereafter – or another reasonable amount of time in the absence of legislative requirements – to allow the individual to access that information in order to understand, and possibly challenge, the basis for the decision

- If retaining personal information any longer would result in a prejudice for the concerned individual, or increase the risk and exposure to data breaches, the institution should safely dispose of it

Accuracy

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 6(2)

Relevant policy requirement: Directive on Privacy Practices

What “accuracy” means: When you use an individual’s personal information to make a decision that directly affects them, ensure that the information you use is correct.

Questions to consider:

- How do you ensure data quality?

- How can individuals request correction of their personal information?

Risk examples:

- Personal information held by an institution may be inaccurate, out-of-date or incomplete

- An institution may make decisions that directly affect an individual based on personal information that is inaccurate, out-of-date or incomplete

- Inaccurate, out-of-date or incomplete personal information may be shared with third parties

- Individuals may not be aware of their right to correct their personal information held by an institution

- Inaccuracies in personal information may lead to negative consequences for the individual

Mitigation examples:

- Periodically test the accuracy of information collected

- Monitor changes made to personal information to ensure they are authorized

- Establish a process for responding to requests to amend or correct personal information

- Notify individuals of the procedures for correcting their personal information

- Advise requesters of the reasons for refusal and recourse available to them if you refuse their correction request

- Allow individuals to add a statement to their personal information when their correction request has been refused

Disposal

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 6(3)

Relevant policy requirement and other references: Directive on Privacy Practices and OPC Guide on Personal information retention and disposal: Principles and best practices

What “disposal” means: Use care to prevent unauthorized access when disposing of personal information.

Questions to consider:

- How will information be disposed of?

- Are there means to dispose of information in various formats (for example, paper, digital)?

- Is the information covered by a RDA?

Risk examples:

- Personal information is disposed of improperly and may be accessed without authorization

- Not all copies of information are disposed of

Mitigation examples:

- Put in place procedures for secure disposal or destruction of personal information or the equipment or devices used for storing personal information

- Have in place an RDA or appropriate interim measure

- Configure systems to delete personal information once the retention period has been reached

- When disposing of equipment or devices used for storing personal information (such as filing cabinets, computers, external hard drives, cellphones and audio tapes), remove or delete any stored information

- Keep a record of the disposal of information

Limiting use

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 7

Relevant policy requirement: Directive on Privacy Practices

What “limiting use” means: Limit your use of individuals’ personal information to your purpose.

Questions to consider:

- What personal information will be used and for what purpose?

- Is information used for:

- the purpose for which it was collected?

- a consistent purpose?

- a purpose for which the information was disclosed to the institution?

- or will the individual’s consent be obtained?

- Are there specific laws or regulations that allow you to use the information in this way?

Risk examples:

- Personal information provided for one purpose may be used inappropriately for a secondary purpose

- An institution may use personal information in a way that is contrary to the reasonable expectations of the individual

Mitigation examples:

- Inform individuals of planned uses of their personal information

- Have in place measures to limit how personal information can be used

- Establish appropriate processes for seeking consent, as necessary

- Document your rationale for considering certain secondary uses as consistent uses

Tip: Interpret the definition of “consistent use” narrowly as it is an exception to seeking consent. This approach is in keeping with the quasi-constitutional status of the Privacy Act and the privacy rights that the statute protects. A consistent use is defined as a use that has a reasonable and direct connection to the original purpose(s) for which the information was obtained or compiled. This means that the original purpose and the proposed purpose are so closely related that one would expect that the information would be used for the consistent purpose, even if the use is not spelled out.

Limiting disclosure

Relevant legal requirements: Privacy Act s. 8(1) and (2)

Relevant policy requirements and other references: Guidance on Preparing Information Sharing Agreements Involving Personal Information, Guidance Document: Taking Privacy into Account Before Making Contracting Decisions, Directive on Privacy Practices, and Policy on Privacy Protection

What “limiting disclosure” means: Limit your sharing of individuals’ personal information.

Questions to consider:

- What personal information will be disclosed, for what purpose and to whom?

- Does the individual consent to the disclosure, or is the disclosure subject to an exemption?

- How will information be shared?

- Are information-sharing agreements in place with third parties with whom information is shared, and do these arrangements include appropriate privacy and security clauses?

- Are there specific laws or regulations that allow you to share the information in this way?

Risk examples:

- Disclosure could occur without legal authority or consent

- Inaccurate, incomplete or out-of-date information could be shared with third parties

- Third parties may inadequately protect personal information that has been shared

- Unauthorized use of or onward disclosure of personal information may occur

Mitigation examples:

- Inform individuals of planned disclosures of their personal information

- Have in place measures to limit sharing of personal information

- Establish appropriate processes for seeking consent, as necessary

- Include robust privacy and security requirements in agreements with third parties with whom information is shared

- Use appropriate safeguards to protect personal information in transit

Safeguards

Relevant legal requirements: Privacy Act s. 7 and s. 8Footnote 3

Relevant policy requirements and other references: Policy on Government Security, Directive on Security Management, Directive on Identity Management, IT Security Risk Management: A Lifecycle Approach (ITSG-33) and Directive on Privacy Practices

What “safeguards” means: Take steps to ensure that personal information is appropriately protected against inappropriate access, use or disclosure.

Questions to consider:

- What security and access controls will protect personal information against loss or theft, as well as unauthorized access, disclosure, copying, use, or modification whether in transit or at rest?

- How are safeguards improved for personal information that is more sensitive?

- How will your institution detect and respond to a breach?

- Does personal information travel or reside outside of Canada?

Risk examples:

- Those without a need to know may gain access to personal information

- An institution may not be able to detect and respond to a breach

- De-identified information may be identifiable when combined with other information, including publicly available information

Mitigation examples:

- Use appropriate physical safeguards (restricted access and locks) institutional safeguards (training and procedures) and technical safeguards (audit trails and encryption) to protect personal information

- Use a variety of safeguards, depending on the information’s sensitivity, amount, distribution, format, and method of storage

- Use anonymous or de-identified information, where possible

- Leverage privacy enhancing technologies, where available

- Have in place a breach response procedure as well as measures to detect a breach

- Include robust privacy and security requirements in agreements with third parties with whom information is shared

- Conduct appropriate security assessments

- Conduct ongoing testing of safeguards to ensure they are functioning appropriately

Tip: The most effective privacy safeguard is not to collect personal information in the first place if you don’t need it.

Tip: The goal of a PIA is to identify the most appropriate level of security in specific circumstances, not the strongest information security possible.

Openness

Relevant legal requirements: Privacy Act s. 9, s. 10 and s. 11

Relevant policy requirements: Directive on Privacy Practices and Policy on Privacy Protection

What “openness” means: Be open, clear and straightforward about your handling of personal information.

Questions to consider:

- Are individuals informed of:

- what personal information is being sought?

- for what purpose and with what authority?

- the consequences for not providing the information?

- how it will be used, disclosed and protected?

- for how long it will be retained?

- rights they may have to access and correct their information?

- How are they informed (for example, signage, forms, privacy notice, Personal Information Bank (PIB))?

Risk examples:

- Individuals may be unaware of the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information

- Notice may not be easily accessible to all individuals

- Important privacy information may be buried in a long and complicated policy

Mitigation examples:

- Make information about your personal information handling practices readily available and easy to understand

- Make information available in a variety of ways and ensure it is consistent across formats (for example, signage, written or verbal notice)

- Whenever possible, notify individuals of your practices at or before the time of collection

- Make a summary of your PIA publicly available

Notice versus consent: In some areas of government activity, seeking consent for treatment of personal information is neither realistic nor appropriate. For example, some services or functions of government cannot be performed effectively in the absence of particular types of personal information. In these cases, government institutions generally rely on legal authority and notice, rather than consent, as the basis for the information activities. Specifically, consent is not required if the personal information is to be used for the authorized purpose for which it was obtained, for a use consistent with that purpose or for a purpose for which it may be disclosed to the institution under subsection 8(2) of the Privacy Act.

Where consent is required, such as in the case of a secondary use of personal information, institutions should consider:

- how consent is obtained (verbally, in writing, etc.)

- what form of consent (implied or express) may be appropriate considering the sensitivity of the information and the reasonable expectations of the individual

- the implications of declining to provide consent

Institutions should seek express consent whenever possible and particularly when the personal information or context is likely to be considered sensitive. They should also allow individuals to withdraw consent at any time, subject to legal or contractual restrictions and reasonable notice, and inform individuals of the implications of such a withdrawal. If withdrawal is not an option, this should be noted at the time of consent.

Refer to s. 7 and s. 8 of the Privacy Act and the Directive on Privacy Practices for more information.

Tip: The federal government publication Information about programs and information holdings is intended to provide individuals with an index of personal information held by government institutions subject to the Privacy Act.

Individual access

Relevant legal requirement: Privacy Act s. 12

Relevant policy requirements: Directive on Personal Information Requests and Correction of Personal Information and Policy on Privacy Protection

What “individual access” means: Give all individuals, whether they are within or outside Canada, access to the information you hold about them and correct it, when necessary.

Questions to consider:

- What is the process for assessing and responding to requests from individuals within or outside of Canada, for access to and correction of personal information in a timely manner?

- How are all individuals, both within Canada and outside Canada, informed of their right of access and correction?

Risk examples:

- Gaps in processes and systems may lead to delays in responding to requests for access to or correction of personal information or information being withheld inappropriately

- Individuals may be unaware of their right to access or correct their personal information held by an institution

Mitigation examples:

- Develop and document a process for responding to access and correction requests

- Inform individuals of their right to request access to and correction of their personal information

- Configure systems so that an individual’s personal information can be retrieved without unreasonable effort

- Establish procedures to validate the identity of individuals requesting access to their personal information

- Advise requesters of the reasons for refusal and recourse available to them when you refuse their access or correction request

- Allow individuals to add a statement to their personal information when their access or correction request has been refused

- Establish a process to inform third parties if inaccurate information has been shared

Tip: Exemptions to providing access to personal information should be interpreted as narrowly as possible

Risk mitigation phase

Now that you have identified the privacy risks associated with your institution’s program or activity, you must decide how to respond. Your risk management approaches and processes will be specific to your institution and will depend on its:

- mandate

- priorities

- risk exposure

- institutional risk culture

- risk management capacity

- partner and stakeholder interests

The risk level before you take into account existing controls and risk responses is referred to as the "inherent" risk level. The remaining risk level after taking into account existing risk controls and responses is referred to as the "residual" risk level. You can have more than one measure to address each risk. For example, you may have a policy combined with a training program and an audit function to reduce a particular risk. Ideally, residual risk levels are low.

Not all risks are equal. If there is a risk that your institution is not complying with the law, you must address it urgently and completely. However, even legally compliant programs may not be privacy friendly. If there remains a risk that your initiative may still have negative impacts on individual privacy, you should work to minimize or eliminate those risks and assess whether or not remaining risks are justified.

Institutions should consider integrating privacy risk management into their broader risk management approach.

Action plan

There is little point investing time or resources in a PIA process and then failing to take action. An action plan can help you track and manage the decisions you’ve made as a result of the PIA and ensure that plans to address privacy risks are, in fact, implemented. For each planned action, specify the:

- area of the institution or particular member(s) of the project team responsible for its implementation

- estimated timeframe for completion

Drafting phase

Once you have assessed and mitigated your program or activity’s risks, you will need to document the results in a PIA report. As mentioned above, the TBS Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment sets out content that must be included in your PIA report. You are encouraged to include additional information, as appropriate. The format of the PIA report can also vary as needed.

PIA report best practices

- Be specific

- Avoid jargon and limit use of acronyms

- Be concise – “more content, fewer words”

- Be action oriented – what do you plan to do?

- Use visual aids, such as tables or diagrams, where appropriate

- Organize your report to assist with readability and reduce the need to re-explain or repeat material

- Create an internal PIA inventory, so that PIAs are organized and accessible for future reference

Approval phase

Next, you will need to obtain internal approvals in accordance with the Directive on Privacy Practices. The approvals should indicate that your institution’s officials accept the residual risk once your mitigation measures are in place. It is an institution’s responsibility to ensure it has met all requirements under the Directive.

Tip: The OPC does not approve, endorse or sign off on PIAs or on government programs or initiatives. We do, however, review the final PIA reports of federal public sector institutions, and provide recommendations where we identify additional risks or gaps.

Reporting phase

TBS policy requires that institutions make select sections of the PIA report publicly available (as per the Directive on Privacy Practices). Public reporting allows individuals to have an idea of how government is using their personal information and helps foster trust in the institution’s operations. The Standard on Privacy Impact Assessment includes a template that federal institutions must use to create their PIA web summaries.

PIA reports (or their summaries) should be clear, unambiguous, and understandable in general, but especially once they are publicly available. Institutions should post, at a minimum, summaries of their PIA reports on the institutional website. These may be accompanied by a link to the relevant PIB description on the Information about programs and information holdings page. You may need to rework summaries to protect interests such as commercial confidentiality, individual privacy, security of information or legal privilege prior to publishing.

Review phase

Privacy risk analysis is an ongoing process that does not stop with the approval of the PIA. You should assess privacy issues (controls, risks, etc.) regularly as the environment changes. In particular, institutions should assess whether the measures implemented are having the intended effect of mitigating privacy risks. Ongoing management of privacy risks can be incorporated into your institution’s overall risk management strategy.

You should treat PIA reports as evergreen documents. During project implementation, it is a good idea to build one or more “PIA checkpoints” into your project plan, where you’ll ask whether anything significant has changed since you did the PIA. For example, changes in technology or the implementation of other related programs may create new risks that you should identify and mitigate.

For relatively minor changes, it may be sufficient to modify the PIA or attach a short addendum. In either case, you should clearly note the relevant changes and analyze the implications (if any). If changes are substantial and result in significant new privacy impacts that were not considered in the PIA, you should do a new PIA in accordance with the Directive on Privacy Practices.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the work of our domestic and international colleagues in the area of PIAs. Their published guidance has been an invaluable source of inspiration. In particular, we wish to thank the following organizations:

- Data Protection Commission of Ireland

- Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario

- Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

- Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of New Zealand

- United States of America Department of Homeland Security

Disclaimer

This Guide is intended as a tool to assist government institutions when determining how best to achieve compliance with the Privacy Act. Nothing in this Guide should be considered to interfere with or limit the discretion of the OPC to carry out its responsibilities, particularly with respect to an investigation of any complaint under the Privacy Act or the undertaking of an audit or review by the OPC under the Act.

- Date modified: