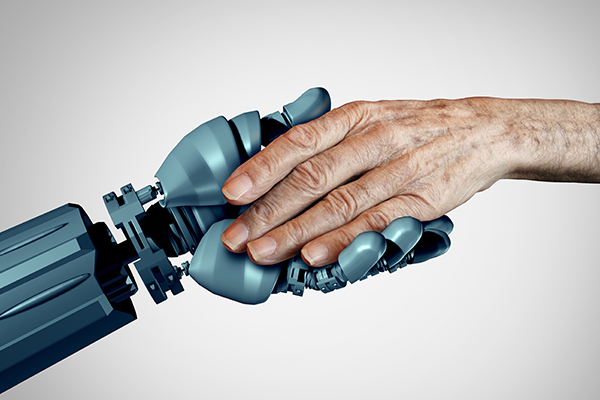

A Robot for Grandma?

Innovative technologies are increasingly being deployed to provide care for aging people. Is it possible for them to attend to the social and emotional needs of seniors in a way that also respects their privacy?

Meet Mary. She’s 85 and continues to live independently in her own home. Every morning, Mary is prompted to take her medication and reminded about the day’s schedule. If she needs a ride, it’s arranged. If the weather is good, a walk is suggested – along with a friendly reminder to bring a bottle of water. Later in the afternoon, she’s offered the opportunity to practice bridge, listen to an audiobook, and schedule a video call with one of her grandchildren.

These activities are not unusual, but who – or what – is performing these social functions may be surprising: Mary is using a ‘social robot’, one of an increasing number of futuristic technologies aimed at supporting seniors and enabling them to live independently.

A fast-growing demographic segment

It’s an oft-repeated fact: Seniors represent the fastest-growing demographic segment in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, the number of seniors is expected to increase rapidly until 2031, when all the baby boomers will have reached the age of 65. By that time, about 23 per cent of Canadians could be seniors – surpassing a population of 10 million – similar to Japan, the world's oldest country. And by 2061, there could be 12 million seniors to eight million children in Canada.

Many seniors want to “age in place” by continuing to live in their own homes to maintain a sense of autonomy. But as they age, these seniors can become more isolated. Mobility and other health issues can prevent them from engaging with programs at local community and senior centres. Their adult children may live elsewhere, work full-time, or already be time-squeezed by the responsibilities of caring for their own children.

“By 2061, there could be 12 million seniors to eight million children in Canada.”

Social isolation is a known risk factor for negative health outcomes. While care workers can provide at-home support, many government-funded services are limited to only a few hours a week, and private caregivers can be prohibitively expensive for many elderly people. And not all seniors want non-family caregivers in their homes.

Innovative technologies for senior care

Such varied and complex challenges have given rise to a relatively new industry: Innovative technologies for senior care. Ranging from smart home devices and digital assistants to, yes, ‘social support robots’ – these devices promise to deliver a range of social support functions. They can boost social connections and activities to decrease isolation. They can play a cognitive support role by providing reminders, prompts, and information retrieval. They also hold the potential to provide conversation and companionship to help address loneliness. Companies developing these digitally networked devices and applications are marketing them as providing social support for seniors and their caregivers, with the laudable goal of enabling seniors to live independently.

However, and here’s the privacy rub, accomplishing these social support tasks means the devices and applications must collect, use, and sometimes share personal data provided by the senior user – whether actively or passively. This begs the question: Are seniors’ privacy interests being protected while they use these devices?

Protecting the data privacy of vulnerable population groups – including women, youth, and people with mental health challenges – has long been an interest of Dr. Andrea Slane, a professor in the Legal Studies Program and Associate Dean of the Faculty of Social Science and Humanities at Ontario Tech University.

Research on protecting senior’s privacy interest

In the course of Slane’s research on privacy and data protection, including related private sector responsibilities, she noticed seniors were a “significantly understudied” demographic in the privacy literature. Around the same time, she also began to notice a “preponderance” of new technologies being marketed to seniors, including social support robots.

“These products are being marketed to seniors as a means for them to retain their ability to live independently, but by their very nature, they involve considerable data collection and processing – it’s part of how they work. That struck me as requiring serious attention,” Slane explains.

With funding support from OPC, Slane, along with Drs. Isabel Pedersen and Patrick C. K. Hung, set about gathering seniors’ ethical concerns and privacy issues with using digital networked technologies – those already in use and those that might be used in future. Current devices commonly used by seniors include desktop and laptop computers, tablets, and smartphones, and some are already using Internet of Things (IoT) devices, including digital home assistants like Amazon Echo and Google Home.

After reaching out to senior centres, the research team organized focus groups in BC, Ontario, and Quebec. The goal? To come up with “good” privacy practice guidelines that companies and other organizations could follow when developing social support technologies for seniors.

Focus on people’s experiences

Because she is a trained lawyer, much of Slane’s past research was focussed on the technicalities of privacy law. But this project proved to be closer in its focus to the actual, lived experiences of people.

“It was quite important to me that this particular project was about collecting impressions from seniors themselves about the new technologies, and about the kind of support that they thought of themselves as potentially needing,” says Slane.

Slane initially thought she would be able to gather privacy best practices from seniors participating in the study, that “seniors will inform me about them." But in the end, the list of “good” privacy practices were “co-created” with the seniors who took part in a series of workshops aimed at gathering their suggestions. In the course of these workshops, Slane realized seniors needed more information about both privacy protection concepts and how the apps and devices they were being asked about work.

“I realized that part of this research has to be about educating seniors, because you can't just ask ‘what do you think your privacy protections should be?’ if they don't really know what the options are,” explains Slane. “In order to really have a meaningful co-creation with seniors, you also need to provide some background education, so they can engage with the issues on a meaningful level.”

A continuous and collaborative approach

Slane is continuing to research the privacy needs of seniors, and continues to adapt the methodologies that best engage seniors in the process. “They really liked talking about these things,” notes Slane, adding. “It's interesting to them. It affects them. This ‘co-creation’ concept will definitely be part of my research going forward.”

In future projects, Slane plans to target seniors who are even more isolated and face greater challenges with living independently, such as those with early stage dementia. And as senior centers across the country and the globe grapple with the pandemic, Slane has embarked on a remote research project with Oshawa Senior Community Centres to see how seniors are using technology to adapt to social distancing restrictions, and explore if better supports can be provided to seniors with a wide range of comfort levels using technology. She is also keeping in touch with the developers of support technologies for seniors, who often don’t consider the specific privacy interests of senior users.

Working with this industry

“For the most part, developers are very hopeful people and have great expectations for their products,” Slane says. “But when I start talking to them about privacy concerns, they don’t know how to deal with them. So they actually need some guidance. Many think that protecting privacy and addressing ethical concerns will be the responsibility of people who come up with applications for their devices. But it needs to be much more upstream than that.”

Slane acknowledges that many of these technologies for seniors are “very hopeful” kinds of projects, like helping seniors feel less lonely, and enabling seniors to be independent longer. Some applications could be appreciated for generations to come – like ones that inspire seniors to tell their life stories and record them.

“But with these projects, and other apps that involve collecting personal information, you always have to think about how to do it in a way that protects seniors and appreciates their unique situations.”

Good Privacy Practices for Developing Social Support Technology for Seniors

With support from OPC, Ontario Tech University’s Dr. Andrea Slane, Dr. Isabel Pedersen, and Dr. Patrick C. K. Hung developed a project to collect seniors’ ethical concerns and privacy issues with using digital networked technologies – both in current use and potential future use.

After holding focus groups in senior centres across the country, the research team worked with seniors to co-create “good” privacy practice guidelines that companies and other organizations can follow when developing social support technologies for seniors.

The team discovered that many seniors find enabling the privacy settings of some applications to be challenging. Many complain about overly complicated, legalistic privacy policies that consequently went unread. Some face even greater barriers to understanding such procedures and policies, leading them to completely opt-out of using a device or application.

To boost the confidence of seniors in using a device, platform, application, or service, Slane and her research team recommend that technology providers follow these “good” privacy practices:

- Seniors value the data protection principle of transparency. Tell them exactly what information will be collected and why through a clear and abbreviated privacy policy.

- Seniors value the data protection principle of meaningful consent.

- Seniors should have access to clear, simplified guides that help them explicitly reason through the benefits, burdens, and risks associated with using a device or application for a particular function.

- Seniors should be recognized as autonomous individuals, with their own particular affinity level for technologies, and their own privacy risk tolerance.

- Seniors require clear, simplified instruction on their data protection options as they choose whether to use a device for a specific function.

- Seniors want companies to proactively protect user privacy, to alleviate some of the burdens to have to constantly check and update their privacy preferences. Make privacy protection a key part of your business.

These practices are excerpted from: “Good Privacy Practices for Developing Social Support Technology for Seniors.”

Technology: Do Not Underestimate Seniors

According to Slane and her research team, when it comes to technology, many seniors are just as capable and interested in new technology as other adults.

“Our focus groups and workshops revealed that seniors engage in a complex reasoning process when deciding whether or not to use a device, platform, or application for a particular function – weighing the benefits against risks to privacy, security, and safety,” notes Slane. “The reasoning process was similar across currently available devices and future devices, such as social robots.”

After working with seniors, Slane cautions anyone studying this group to avoid overgeneralizations, including:

- “Seniors are not tech savvy”

Some seniors are not particularly tech savvy, but many are just as capable and interested in new technology as the general adult population. Yet, younger family members sometimes assume their elders cannot make wise decisions about privacy protection. - “Seniors are a vulnerable demographic”

While some seniors are vulnerable to manipulation and deceit, seniors as a whole should not be assumed to be more vulnerable than other adults.

- “Seniors are a uniform group”

Seniors do not all reason along the same lines when it comes to how best to approach privacy protection. Most espouse dominant privacy protection principles that encourage transparency of data handling practices and meaningful choices for users to provide or withhold consent.

Some seniors preferred clearer rules tailored to data handling practices for devices and applications aimed at senior users. If clear rules for companies serving the senior demographic were created, this would alleviate some of the burdens on individual seniors to understand and make active privacy protective choices.

What Can “Social Support” Robots Do for Seniors?

research assistants Jayden Cooper and Dallas Hill.

They are accompanied by “Misty”, a robot designed

to perform human-to-robot and robot-to-robot

interactions using vision algorithms, supervised or

autonomous control, and voice recognition.

With the number of caregivers who can support seniors on a steady decline, robots are being pitched as a way to help close the gap and supplement human support to enable seniors to remain independent longer. According to researchers from Ontario Tech University, Drs. Andrea Slane, Isabel Pedersen, and Patrick C. K. Hung, such robots are being designed to handle a range of tasks and functions to attend to the social and emotional needs of aging people, including:

- Facilitating social connections and activities to address social isolation

- Monitoring for health and safety issues

- Providing reminders, prompts, and information retrieval, both in everyday use and more specifically to address short-term memory loss or other cognitive ability reductions

- Enabling conversation and companionship to provide reassurance, encouragement, and entertainment, especially to address loneliness

What do you think? Check out these websites of companies currently selling social support robots: Mabu, ElliQ, and Temi. Would you buy one? What would be your privacy concerns?

Other articles from Real Results

Parenting in the digital age

Parenting in the digital age

Digital Stalking on the Rise in Canada

Digital Stalking on the Rise in Canada

Is “Meaningful Consent” a Contradiction in Terms?: Three Design Jams Seek the Answer

Is “Meaningful Consent” a Contradiction in Terms?: Three Design Jams Seek the AnswerDisclaimer: The OPC’s Contributions Program funds independent privacy research and knowledge translation projects. The opinions expressed by the experts featured in this publication, as well as the projects they discuss, do not necessarily reflect those of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

- Date modified: