Joint investigation of the Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta, and the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia

PIPEDA Findings #2020-004

October 28, 2020

Overview

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC), Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta (OIPC AB) and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia (OIPC BC), collectively referred to as “the Offices” commenced a joint investigationFootnote 1,Footnote 2 to examine whether The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited (CFCL) was collecting and using personal information of visitors to its Canadian malls, without valid consent, via:

- Anonymous Video Analytics (AVA) technology installed in “wayfinding” directories; and

- mobile device geolocation tracking technologies.

Our findings in respect of these two issues are detailed below.

CFCL collected and used personal information, including sensitive biometric information, via the AVA technology without valid consent.

The AVA technology: (i) took temporary digital images of the faces of any individual within the field of view of the camera in the directory (retained in computer memory briefly during processing); (ii) used facial recognition software to convert those images into biometric numerical representations of the individual faces (sensitive personal information that could be used to identify individuals based on their unique facial features); and (iii) used that information to assess age range and gender.

CFCL represented that the numerical representations were not retained beyond processing. However, our investigation revealed that CFCL’s AVA service provider had collected and stored approximately 5 million numerical representations of faces on CFCL’s behalf, on a decommissioned server, for no apparent purpose and with no justification.

CFCL explained that it collected information via AVA for purposes of monitoring foot traffic patterns and predicting demographic information about mall visitors. We found no evidence that CFCL had used the biometric information, including any of the retained numerical representations, for identification purposes.

CFCL also retained approximately 16 hours of video recordings, some including audio, which it had captured during a calibration (or testing) phase of the technology at two malls.

CFCL asserted that to the extent that it required consent, such consent was obtained via its privacy policy. We found that this was inadequate. Firstly, an individual would not, while using a mall directory, reasonably expect their image to be captured and used to create a biometric representation of their face, which is sensitive personal information, or for that biometric information to be used to guess their approximate age and gender. As such, CFCL should have obtained express opt-in consent. Further, we reviewed CFCL’s privacy policy and determined that the language was overly broad, and buried in the middle of a 5,000 word document, which would not be easily accessible to individuals while they are engaging with a mall directory. We found that the privacy policy language was not sufficient to support meaningful consent for CFCL’s AVA practices.

Finally, we noted that while shoppers were directed, by stickers displayed at mall entrances, to visit guest services to obtain a copy of CFCL’s privacy policy, when we asked a guest services employee at one of CFCL’s malls for that policy, they were confused by the request.

As a result of these findings, we made several recommendations. We recommended that CFCL either: (i) obtain meaningful express opt-in consent and allow individuals to use its mall directories without having to submit to the collection and use of their sensitive biometric information; or (ii) cease use of its AVA technology. While CFCL expressly disagreed with our findings, it advised that it had ceased use of the technology in July 2018, and that it had no current plans to resume that use. CFCL has also, pursuant to further recommendations by our Offices, deleted the numerical representations of faces and audio/video recordings in its possession which were not required for legal purposes. It has confirmed that what information has been retained will not be used for any other purposes outside of those required for compliance with the law. CFCL also provided privacy-related training to guest services employees. As a result, we found the matter to be well-founded and resolved.

Our Offices asked CFCL to provide a commitment to follow our recommendations with respect to ensuring valid consent if they were to resume use of AVA technology in the future. CFCL indicated that if it did resume use of the AVA technology, it would obtain adequate consent, “in accordance with the applicable privacy legislation and consistent with the Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent”. However, it refused to commit to obtaining express opt-in consent consistent with our recommendations. We find this concerning given that CFCL disagreed with our analysis and interpretation of the law in this case. For example, CFCL continues to maintain, contrary to our findings, that they were not collecting personal information via the AVA technology.

CFCL did not collect the location information of identifiable individuals via mobile device tracking technology in its malls, such that it did not require consent for the practice.

We found that the information collected from mobile devices of shoppers, who were not logged into Wi-Fi in CFCL malls, did not constitute personal information. More specifically, the hashed and randomized MAC address (device identifier), coupled with non-granular “zone” geolocation information collected using Wi-Fi triangulation, did not constitute personal information in this context, as there was not a serious possibility that this information could be linked, either alone or with other available information, with the mobile device holder.

With respect to individuals who log in to CFCL’s free Wi-Fi service, via a process that required them to provide personal information, we originally understood, based on the evidence gathered during our investigation, including from CFCL and its Wi-Fi service provider, that CFCL was collecting triangulated device geolocation information and linking it with identifiable device users’ Wi-Fi accounts. We therefore made certain preliminary recommendations to CFCL with respect to the consent we would expect for this practice. However, in response to a preliminary report issued by our Offices, CFCL clarified, and its third-party Wi-Fi service provider verified, that the geolocation information described above could not in any practical manner be associated with, or linked to, logged-in Wi-Fi accounts, such that it was not personal information in that context. We therefore determined the matter to be not well-founded.

We did note, however, that CFCL was seeking consent for “special location-based offers”, despite the fact that it was not engaged in the practice. Further to our recommendation, CFCL did remove such language from its privacy policy, and added language making clear what limited location information is collected and associated with Wi-Fi accounts (i.e., only the CFCL property in question).

Finally, we note that CFCL’s third-party Wi-Fi service provider offers the option to associate triangulated “zone” information to accounts, and that CFCL did include, in its privacy policy, the prospect of using geolocation information to deliver location-based offers. We therefore recommended that CFCL commit to implementing our preliminary recommendations should it decide to activate this functionality and associate geolocation information with Wi-Fi accounts in future. Specifically, we would expect CFCL to: (i) support express consent for such geolocation practices via a clear and prominent notice on the Wi-Fi log-in page; and (ii) provide a clearly explained and easily accessible opt-out option. CFCL again refused, claiming that these recommendations were speculative.

Background

- This report of investigation examines The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited’s (“CFCL”) compliance with Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA”), Alberta’s’ Personal Information Protection Act (“PIPA AB”), and British Columbia’s Personal Information Protection Act (“PIPA BC”) – referred to collectively as the “Acts”.

- CFCL is one of the largest owners, operators and developers of offices, retail and mixed-use properties, including shopping malls, in North America.

- This joint investigation was launched in the wake of numerous media reports that raised questions and concerns about whether CFCL was collecting, using and/or disclosing personal information using facial analytics technology, via in-mall directories, without adequate consent. The technology, which CFCL referred to as Anonymous Video Analytics (“AVA”) technology,Footnote 3 was installed on digital wayfinding directories, which are effectively touch screen digital map systems that allow visitors to locate stores and find their way through CFCL shopping malls. In the context of this report, AVA technology covers all elements of the software suite and hardware elements involved in CFCL’s AVA implementation.

- Initial media reportsFootnote 4 regarding CFCL’s use of AVA technology in its directories surfaced in July 2018, after an individual posted a photoFootnote 5 on RedditFootnote 6 taken at CFCL’s Chinook Centre in Calgary, Alberta, showing a display screen with coding language that included “FaceEncoder” and “FaceAnalyzer” – leading the media to report that CFCL was using facial recognition technologies.

- Satisfied that reasonable grounds existed to investigate these matters, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia and Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta each initiated investigations pursuant to s.11(2) of PIPEDA, s.36(1)(a) of PIPA BC, and s.36(1)(a) of PIPA AB, respectively. In August 2018, OIPC AB also received a complaint about CFCL. In December 2018, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (“OPC”), the Office of the Information & Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia (“OIPC BC”), and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta (“OIPC AB”) decided to conduct the investigation jointly, at which time, the complaint received by OIPC AB was put in abeyance, pending the outcome of this joint investigation.

- In light of subsequent media reportsFootnote 7 and information obtained during the preliminary stages of the investigation into CFCL’s deployment of the AVA technology, the scope of the joint investigation was expanded to determine whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for its collection, use, and disclosure of mall visitors’ personal information, including geolocation and Media Access Control (MAC)Footnote 8 address, via mobile device geolocation technologies. Further information discovered during the course of the investigation prompted us to also consider the retention of personal information obtained through the AVA technology.

- Finally, in light of the fact that the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec (the “CAI”) was also examining the issue of AVA technology installed in CFCL shopping malls located in the Province of Quebec, the OPC, OIPC BC and OIPC AB entered a collaboration arrangement with the CAI in March 2019 in order to coordinate investigative efforts.

Methodology

- The investigative team sought representations and records relating to the possible collection, use or disclosure of personal information by CFCL with regard to both the AVA technology and geolocation technologies. These representations were sought from CFCL directly, as well as from the following third parties: (i) Mappedin, the third party service provider of the wayfinding directories (and AVA technology therein); and (ii) Aislelabs, the third party service provider for the geolocation technologies.

- After reviewing the initial representations from CFCL, the investigative team conducted a site visit at CFCL’s headquarters in Toronto, Ontario, during which it interviewed key personnel and viewed CFCL’s wayfinding directory in action, and the AVA technology therein. The investigative team also securely extracted records from the wayfinding directory for forensic analysis by the team’s Technology Analysts.

- Subsequently, the investigative team also conducted a site visit at Mappedin’s headquarters, during which it interviewed key personnel, and securely extracted records for forensic analysis by the team’s Technology Analysts. Further, we obtained a copy of the database containing all of the data sent by the AVA technology installed in the wayfinding directories while the technology was operational. We note that this database was stored on a decommissioned server, and was not being used for production purposes.

- The investigation also included a visit to a CFCL property (CF Eaton Centre), with the specific goal of assessing CFCL customer service staff’s ability to respond to basic customer privacy requests (e.g., provision of a copy of CFCL’s privacy policy).

- Over the course of the investigation, we also considered the following material relied upon by CFCL:

- CFCL provided a third-party analysis report (the “Third-Party Report”) produced by an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Engineering at the Bar Ilan University in Israel (“the professor”) whose research relates to high computer vision, machine learning, biometrics, and signal processing;

- A white paper titled Anonymous Video Analytics (AVA) technology and privacy,Footnote 9 published by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario; and

- A white paper entitled Building Privacy Into Mobile Location Analytics (MLA) Through Privacy by Design,Footnote 10 published jointly by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, and Aislelabs.

- Upon completion of our investigation, we issued a preliminary report of investigation to CFCL, which set out and explained the rationale for our preliminary conclusions and identified several recommendations. We then met with CFCL to address any questions or comments they had, and to discuss our recommendations. Subsequently, in its response to our preliminary report, CFCL committed to implement a number of our recommendations which would bring it into compliance with Canadian privacy laws. CFCL also provided further submissions and factual clarifications, which led our Offices to seek further commitments to ensure that CFCL would not contravene Canadian privacy laws through the future launch or reinstitution of practices similar to those examined in our investigation. CFCL refused to provide those commitments. All of the above is detailed in this final report.

- The investigation and findings focus on CFCL’s legal obligations under the above-mentioned Acts. While this report examines the practices of certain third parties who provided services to CFCL, it does not draw any conclusions about the legal obligations of these parties, or any other organization or individual.

Issues

- The issues in this investigation are:

- Whether CFCL’s use of the AVA technology, via wayfinding directories, resulted in the collection, use and/or disclosure of personal information; and if yes,

- Whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for that collection, use and/or disclosure; and

- Whether CFCL retained that information for longer than necessary; and

- Whether CFCL’s use of mobile device geolocation tracking technologies resulted in the collection, use and/or disclosure of personal information; and if yes, whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for that collection, use and/or disclosure.

- Whether CFCL’s use of the AVA technology, via wayfinding directories, resulted in the collection, use and/or disclosure of personal information; and if yes,

CFCL’s Jurisdictional Challenge

AVA Technology

- At the outset of our investigation, and throughout its course, CFCL objected to our jurisdiction with respect to its use of the AVA technology, on the basis that the use of the technology did not result in the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information.

- In its representations, CFCL asserted that the information processed and gathered through the AVA technology was not personal information because it was anonymous, and in no way could it be used, alone or in combination with other information, to identify an individual. CFCL contended that all processing occurred locally and in real time, and at no time was an image, photograph or video created – except during testing and calibration, as covered at paragraph 54 of this report.

- CFCL explained that no attempt was made to obtain a positive identification of individuals within the visible field of view of the camera, and that the digital images were not matched against a database of known individuals.

- CFCL further represented that it was not engaged in the collection of personal information as defined by the Acts because nothing was “captured” by the AVA technology, and that “the absence of an ‘identifiable individual’ renders any ‘capture’ insufficient to qualify as collection of personal information”.

- Ultimately, after consideration of CFCL’s representations, and for the reasons outlined under “Issue 1” below, we determined that CFCL was collecting personal information via its AVA technology, such that we had jurisdiction to investigate this matter.

Geolocation Technology

- CFCL also objected to our Offices’ jurisdiction with respect to its use of geolocation technologies across its properties, on the basis that MAC addresses do not constitute personal information, and that the geolocation is about a device and not about an identifiable individual.

- In order to support its argument, CFCL drew a comparison with license plates on vehicles, and referred to the Alberta Court of Appeal’s decision in Leon’s Furniture v. Alberta (Information and Privacy Commissioner).Footnote 11 CFCL asserted that MAC addresses are analogous to license plates:

“It is the mechanism that allows the vehicle to participate in the network of roads, it is visible and intended to be visible both to other vehicles and owners/operators of the roadways, and it is unique to that vehicle. Importantly, like a license plate, a MAC address is unique to a device, not an individual.”

- In addition, CFCL further supported its position by referring to a past OPC caseFootnote 12 wherein the OPC held that IP addressesFootnote 13 can constitute personal information if they can be associated with or linked to an identifiable individual.

- Our Offices considered CFCL’s arguments as well as its representations, in determining whether CFCL did, in fact, collect personal information in the form of Wi-Fi triangulated geolocation data. As detailed under “Issue 2” below, our preliminary conclusion was that CFCL was collecting personal information via mobile-tracking technologies. However, subsequent to the issuance of our preliminary report, based on clarifications from CFCL and Aislelabs, we determined this not to be the case.

Issue 1: Whether CFCL’s use of the AVA technology, via in-mall directories, resulted in the collection, use and/or disclosure of personal information, and if yes, whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for the collection, use and/or disclosure; and whether CFCL retained such information longer than necessary

CFCL Representations and our Investigation

Overview of CFCL’s AVA Implementation

- CFCL contracted with a third-party company, Mappedin, to provide CFCL with software and support services for interactive digital wayfinding directories, which CFCL installed in many of its retail properties across Canada. Mappedin describes itself as providing an indoor geographical information system. The organization works with nine out of ten of the largest malls in Canada, including some owned by CFCL, and claims that it seeks to help make the indoors more discoverable in stores, hospitals, campuses, and airports around the world. Additional related services under the contract with CFCL include map design, user experience development, and ongoing support and hosting.

- The wayfinding directories all contained optical devices (i.e., cameras) behind protective glass on the periphery of the screen, such that they were not easily noticeable. The cameras were non-operational when first installed because they were not supported by underlying software. CFCL advised that AVA technology, consisting of a particular software package, was first installed by Mappedin on June 13, 2017 on a test basis, and then disabled and removed on December 1, 2017, (“Testing Period”). The AVA technology was subsequently rolled out in 12 malls across Canada (roughly 60% of directories) between May 31 2018 and July 31 2018.Footnote 14 CFCL indicated that they considered this implementation to be a “pilot project”. The AVA technology was operational in wayfinding directories in the following shopping malls:

Property Province CF Market Mall Alberta CF Chinook Centre Alberta CF Richmond Centre British Columbia CF Pacific Centre British Columbia CF Polo Park Manitoba CF Toronto Eaton Centre Ontario CF Sherway Gardens Ontario CF Lime Ridge Ontario CF Fairview Mall Ontario CF Markville Mall Ontario CF Galeries d’Anjou Quebec CF Carrefour Laval Quebec - According to CFCL, during the initial testing and calibration period (as described in paragraph 54), and between May 2018 and July 2018, when the AVA technology was operational, the technology generated data, which was then sent for analysis by Mappedin, which provided CFCL with anonymous, aggregate insights into traffic patterns and directory use.

Further details regarding Mappedin

- According to the latest Master Agreement (the “Agreement”) between CFCL and Mappedin, dated July 20, 2017, all information provided by CFCL remained CFCL’s sole and exclusive property. It further provided that all data produced under the Agreement was shared property between CFCL and Mappedin, and licensed to CFCL for use and distribution to any third party by CFCL (except under the circumstance where such third party was deemed by Mappedin as a competitor). We note that while the Agreement did mention the integration of webcams, it did not make any reference to the AVA technology. Nevertheless, based on the terms of the Agreement, we understand that CFCL remained responsible for information collected by Mappedin on its behalf.

- In representations to our offices, Mappedin advised that it does not use the information obtained in the context of the Agreement for any purposes other than to provide the contracted services. Mappedin further stated that it does not share, and has not shared any such information with third parties.

The AVA Technology

- In its representations to the investigative team, CFCL described the AVA technology as “facial detection software”. It stated that the AVA technology assessed objects coming into the field of view of the camera in real time to determine if there was a human face present. If the underlying software detected a human face present, the software would then produce assessments of the probable gender and age range for that face. CFCL stressed in its submissions that at no time was the AVA technology capturing images or any other personal information since the gender and age range outputs were anonymous, and that “[n]o information other than the anonymous output data is retained.”

- As noted in paragraph 12, during the course of the investigation, CFCL retained the professor to conduct a study of the AVA technology for the investigative team’s consideration. The Third-Party Report was provided to us following the initial site visit. CFCL has maintained that the AVA technology did not have any facial recognition capabilities; however the report contradicts this assertion to the extent that it references the use of a software called FaceNet, which is “facial recognition” software.

- Following our receipt of the Third-Party Report, we reached out to the professor in order to seek more information with regard to the methodology used to conduct the analysis found in the report.

- The professor indicated that his opinion was based on the following materials provided by CFCL’s external legal representatives:

- A “snapshot” of the AVA technology (consisting of parts of the programming code);

- A copy of the “Notification of Site Visit” issued to CFCL by the OPC;

- The Notice of Joint Investigation issued to CFCL by the OPC, OIPC BC and OIPC AB; and

- A copy of a letter provided to the OPC by CFCL, responding to questions posed by the investigative team in the course of the investigation.

- In the Third-Party Report, the professor made the following conclusions:

“It is my opinion that the AVA software does not report any personal information of the customers. The stored gender and coarse age estimates generated by the system are anonymous and cannot be tracked back to a particular customer.”

- Despite the conclusions of the Third-Party Report, our investigation determined that the AVA technology in question operated differently than initially represented by CFCL, and that it indeed resulted in the collection of personal information, as detailed below.

- We established that the AVA technology performs a number of sequential steps in generating and collecting demographic information, from image input to demographic output (age and gender estimation). These steps are, as referred to in the Third-Party Report submitted by CFCL: (i) face detection; (ii) face encoding; and (iii) face tracking.

- CFCL’s initial representations stated that the AVA technology relied on an open-source software called Rude CarnieFootnote 15 in order to generate age and gender estimations. The developers of that software describe the purpose of the software as being able to “[d]o face detection and age and gender classification on pictures”.

- After reviewing the records extracted during our site visit at CFCL’s headquarters, we learned that the AVA technology employed another softwareFootnote 16 named FaceNet, described as a “face recognizer”. As noted in paragraph 31, this was confirmed in our subsequent review of the Third-Party Report. On the software’s webpage, a research paperFootnote 17 provides an in-depth review of the software, describing it as being a “unified system for face verification (is this the same person), recognition (who is this person) and clustering (find common people among these faces)”.

Face detection and tracking

- Our investigation confirmed that the first step undertaken by the AVA technology was facial detection. The technology was trained to detect the visual formation of one or more human faces within the field of view of the camera installed in the wayfinding directory.

- Once the technology detected what it assessed to be a human face, it generated a bounding box around the face, and captured the image therein for conversion and processing. This “capture” resulted in an actual digital image – or photograph – of the face being retained for a period of a few milliseconds. We do note that, save for the testing and calibration period (see paragraph 54), no persistent image was retained after this processing.

- Our investigation further revealed that during the detection process, the technology also has the ability to, and does, differentiate faces from one another should there be more than one face in the field of view of the camera. In order to do so, the technology attributed a unique identifier, a random number, to each face detected.

- Mappedin represented that the software was capable of assigning a unique identifier (“unique identifier”) to each face present in the field of view; however, they indicated that these unique identifiers were “randomly assigned” and “non-identifying”. Both Mappedin and CFCL indicated that this feature was only in place so that the AVA technology could track and differentiate individual faces within the field of view of the camera. As such, should a user exit the field of view and subsequently return, the AVA technology would assign a new random unique identifier. An example of one such unique identifier can be found in the screen capture at paragraph 53 (referenced as “id”).

- Contrary to representations from CFCL stating that only the age and gender demographic information was retained, in the course of our investigation, we discovered that Mappedin, on behalf of CFCL, collected and retained these unique identifiers in its database, along with additional information associated therewith (including, most importantly, numerical representations of individual faces captured - see paragraphs 44 & 53 of this report). When asked the purpose for such collection, Mappedin was unable to provide a response, indicating that the person responsible for programming the code no longer worked for the company.

Face encoding and embedding

- In order for the technology to differentiate and track individual faces interacting with a wayfinding directory, the AVA technology converted and encoded the captured images, which involved the computation of a series of measurements of each face. This process generated a numerical representation, through an embedding process, of each detected face. Once this process was complete, the captured images of faces were overwritten.

Age and gender estimation

- Our investigation confirmed that as the captured images are processed, the AVA technology estimates the probability that the face in question falls into each of eight pre-defined age groups. These are:

0-2 4-6 8-12 15-20 25-32 38-43 48-53 60-100 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 - The assessment captures these probabilities in the form of numerical values. As the sample output below demonstrates, the technology made the determination that there is a significantly higher probability that the subject would fall into age group number 6 (38-43) or 7 (48-53) than any of the other groups:

Figure 1: Sample output from the AVA technology Text version of Figure 1

This screen capture shows a sample output from the AVA technology to help demonstrate the function of age estimation. These values are derived from analysis of a visitor’s face by AVA and indicate the probability that the visitor falls into a pre-defined age group. The highlighted numbers demonstrate that the AVA technology estimates that this particular visitor most likely falls into the range of 38-43 (54%) or 48-53 (33%).

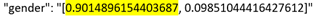

- A similar assessment process occurs for gender estimation, though the values are divided between binary options: male or female. In the sample output below, the AVA technology determined that there was a 90% probability of the face being the first binary option (male):

Figure 2: Sample output from the AVA technology Text version of Figure 2

This screen capture shows a sample output from the AVA technology to help demonstrate the function of gender estimation. These values are derived from analysis of a visitor’s face by AVA and indicate the probability that the visitor is male or female. The highlighted numbers demonstrate that the AVA technology estimates that there is a 90% probability that this visitor is male.

- CFCL and Mappedin both represented that the entirety of the age and gender estimation process summarized above occurs in milliseconds and that each image of a face is only stored in computer memory for the duration of that process. Our investigation confirmed that assertion. However, as noted in paragraph 50, additional information was collected and used in conjunction with the processing of the images.

Additional information sent to Mappedin

- As previously mentioned, CFCL represented that the only information collected and retained through the deployment of the AVA technology was anonymous demographic information. It further provided that Mappedin “simply” analyzed the demographic information to provide CFCL with “anonymous, aggregate insights into traffic patterns and directory usage.” However, as outlined above, our investigation discovered that Mappedin, on behalf of CFCL, collected, used and retained significantly more information than CFCL originally indicated to the investigative team.

- Our forensic analysis of the data extracted from the wayfinding directory during the CFCL site visit revealed that in addition to the demographic information (age and gender), the AVA technology was collecting and/or generating the following information in respect of each face detection event, which was pushed to the Mappedin servers where it was retained on behalf of CFCL:

- A unique identifier for the wayfinding directory in which the collection occurred;

- A unique identifier for the camera used for the collection;

- A unique identifier for tracking and differentiating faces in the field of view;

- A numerical representation of individual faces;

- The property in which the camera is located; and

- A timestamp.

- Following the site visit, we obtained from Mappedin the database of all information it collected, used and retained on behalf of CFCL in relation to the AVA technology. Through forensic analysis of the database, we further confirmed that CFCL, via Mappedin, had been collecting, using and retaining more than the age and gender estimation.

- In total, for the period during which the AVA technology was operating, CFCL, via the AVA technology, collected, used and retained 5,061,324 numerical representations of faces, from an unknown number of individuals.

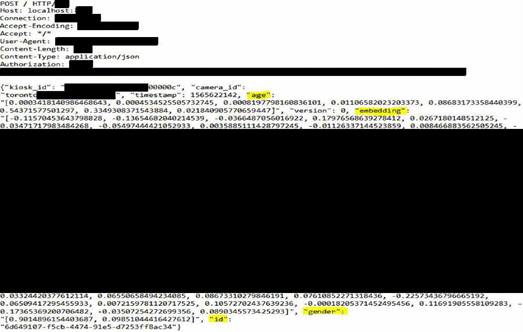

- Below is a screen captureFootnote 18 of the information collected and retained in Mappedin’s database for a single face processed by the AVA technology:

Figure 3: Sample output from Mappedin’s servers Text version of Figure 3

This screen capture shows a sample output from Mappedin’s servers to illustrate the type of information collected and stored by the AVA technology when the image of an individual’s face is processed. This capture includes the age and gender estimate, unique identifier for differentiating the face, and the numerical representation of the visitor’s face. The heading of each set of values has been highlighted. Certain information in this image has been redacted for anonymization purposes, namely: the kiosk and camera identifier pointing to a specific location, authorization code, and some numerical facial representation values (which are in the same format as the values above and below the redaction).

Information Collected During the Testing and Calibration Period

- CFCL advised us that a testing and calibration exercise was undertaken before it deployed the AVA technology. Specifically, CFCL ran the calibration exercise at the CF Toronto Eaton Centre and CF Sherway Gardens, both located in Ontario, on April 29, May 12 and May 13, 2018 (“Calibration Period”). The Calibration Period generated sixteen one-hour videos, which Mappedin retained on behalf of CFCL.

- We note that during our analysis of the videos, we found that in three of the sixteen videos, the audio function had been enabled, which resulted in yet another dimension to the collection, use and retention of personal information via audio recordings.

CFCL’s Privacy Communications regarding AVA

- Notwithstanding the evidence revealed through this investigation, CFCL took the position that since it was not, in its view, collecting personal information via the AVA technology, other than during the testing and calibration period, it was not required to provide notice to its customers regarding the practice.

- We asked CFCL if it had taken any measures to inform individuals that it was conducting testing of the AVA technology, to which CFCL represented: “to the extent any personal information was collected during the testing phase, this is clearly set out CFCL’s Privacy Policy…”.Footnote 19

- CFCL then referred to a passage in its Privacy Policy (last updated July 20, 2016) that reads as follows:

2. IDENTIFYING PURPOSES

“We collect personal information that is relevant for the purposes of providing services to our guests, service providers and clients (which includes retailers and occupants of our properties); securing our properties, websites and mobile applications; meeting our legal obligations; promoting, advertising and marketing our services and, in some cases, the products and services of our clients; and researching and developing new products and techniques to improve our services, business, our properties, websites, and mobile applications.”

[…]

WHAT TYPES OF PERSONAL INFORMATION DO YOU COLLECT AND USE?

“Some of our properties are also equipped with technologies such as ibeacons (sensors) and cameras that we use to monitor foot traffic patterns and may that may [sic] assist us in predicting demographic information about our visitors during your visit to our properties.”

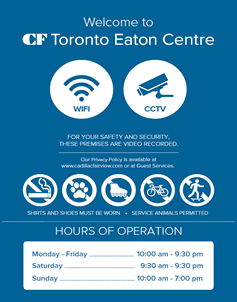

- CFCL further stated that decals on the entrance doors of all shopping malls directed guests to CFCL’s Privacy Policy should they want more information on CFCL’s practices. We note that, as displayed in the figure below, installed at the CF Toronto Eaton Centre from May to June 2018, the only stated purposes of video recording are for “safety and security”.

Figure 4: Decal on the entrance doors of the CF Toronto Eaton Centre Text version of Figure 4

Welcome to CF Toronto Eaton Centre

For your safety and security these premises are video recorded

Our Privacy Policy is available at www.cadillacfairview.com or at Guest Services.

SHIRTS AND SHOES MUST BE WORN | SERVICE ANIMALS PERMITTED

HOURS OF OPERATION

Monday – Friday …………………….. 10:00 am – 9:30 pm

Saturday………………………………….. 9:30 am – 9:30 pm

Sunday…………………………………….. 10:00 am – 7:00 pm

Analysis

Was there Collection, Use and/or Disclosure of Personal Information?

- In our view, CFCL clearly did collect and use, via the AVA technology, personal information, as defined in the Acts, including: captured images of faces, the numerical representation assigned to each face and the assessment of age range and gender. CFCL disagrees with this finding. We also note that while CFCL collected and used numerical representations of faces suitable for facial recognition, we found no evidence that it sought to, or did, use these representations for the specific purpose of identifying individuals.

- Subsection 2(1) of PIPEDA, section 1 of PIPA BC and paragraph 1(1)(k) of PIPA AB all define personal information as information about an identifiable individual. Courts have found in various cases that personal information must be given a broad interpretation as to give effect to the legislation’s intended purpose.Footnote 20 Courts have also found that information will be considered personal where it is reasonable to expect that a person can be identified from the information at issue when combined with information from sources otherwise available.Footnote 21

- We do not accept CFCL’s assertion that the AVA technology worked entirely in real-time. Rather, the captured images of individual faces coming into the field of view of the cameras were kept in memory, albeit for a very short period of time, while the technology processed these images, with the resulting information and analyses to be used thereafter.

- The images of individual faces captured by the AVA technology through the cameras installed on the wayfinding directories are, in and of themselves, clearly personal information. Past cases have consistently found that images or photographs of individuals can and do constitute personal information under PIPEDA,Footnote 22 PIPA BCFootnote 23 and PIPA AB.Footnote 24 As such, while we agree that the captured images were held in memory for a very short period, that practice did represent a collection of personal information.

- Moreover, our investigation found that the images captured by the technology were used to generate additional personal information including numerical representations, age range and gender of individual faces, which were then collected and retained for a much longer time period.

- In particular, we are of the view that the embedding process, which results in the creation of a unique numerical representation of a particular face, constitutes a collection of biometricFootnote 25 information, because that information is uniquely derived from a particular identifiable individual, and could be used, and is used in the context of the AVA technology in this case, to distinguish between different individuals. Based on CFCL and Mappedin’s representations regarding the use of FaceNet software to detect and differentiate faces during the collection process, we have determined that these numerical representations are created by FaceNet to identify a number of facial features, which would normally enable the software to recognize specific individuals.Footnote 26 We do note that consistent with CFCL’s and Mappedin’s representations, we found no evidence that either were using the technology for the purpose of identifying individuals. Nonetheless, the collection, use and retention of approximately 5 million such numerical representations, which we view as sensitive personal information, occurred via the AVA technology.

- As stipulated by the courts, information will be about identifiable individuals when the information in question, together with other available information would tend to or possibly identify them.Footnote 27 “About” is also defined as being information that is not just the subject of something but also relates to or concerns the subject – such as images and/or biometric information.Footnote 28 In that regard, previous Alberta investigations have found biometric information to be personal information.Footnote 29 Similarly, OPC’s guidance on biometrics,Footnote 30 and past investigations, clearly affirm that biometric information is personal.Footnote 31

- The England and Wales High Court of Justice recently held that biometric data, in the form of numerical representations of faces, enables the unique identification of individuals with some accuracy, which is what distinguishes it from other forms of data.Footnote 32 As the court stated:

Like fingerprints and DNA, AFR [Automated Facial Recognition] technology enables the extraction of unique information and identifiers about an individual allowing his or her identification with precision in a wide range of circumstances. Taken alone or together with other recorded metadata, AFR-derived biometric data is an important source of personal information. Like fingerprints and DNA… it is information of an “intrinsically private” character. The fact that the biometric data is derived from a person’s facial features that are “manifest in public” does not detract from this. The unique whorls and ridges on a person’s fingertips are observable to the naked eye. But this does not render a fingerprint any the less a unique and precise identifier of an individual. The facial biometric identifiers too, are precise and unique [emphasis in original document].Footnote 33

- Additionally, given that the numerical representations of individual faces were created from images already captured by the AVA technology, we are also of the view that the creation of such biometric information from the images constituted a distinct and additional collection and use of personal information regardless of the fact that the original images were not retained.

- With respect to the White Paper referenced at paragraph 12 of this report, for the following reasons, we cannot accept CFCL’s submission that the paper supports the assertion that CFCL’s AVA technology did not violate PIPEDA, in that no personal information was “recorded” (other than during the testing and calibration period):

- First, we note that the White Paper was prepared in the context of Ontario’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (“FIPPA”). Subsection 2(1) of that legislation defines “personal information” as “recorded information about an identifiable individual”, while paragraph 2(1)(a) defines “record” as “any record of information however recorded, whether in printed form, on film, by electronic means or otherwise”, including “a photograph”. PIPEDA, PIPA BC and PIPA AB, however, define “personal information” differently, and do not require the information to be “recorded” to constitute personal information. Therefore, compliance with these Acts cannot be resolved by reference to a report prepared in a different legislative context.

- Furthermore, in our view, as outlined above, personal information is “recorded” by the AVA technology in this case, since digital images must be temporarily captured in order for the technology to process them, and then further biometric and other data is derived from those images and retained. As a result, whether realized through a photo or a set of data-points, the characteristics of a face are being recorded.

- We also do not accept CFCL’s assertion that the Morgan v. Alta Flights Inc. decisionFootnote 34 has any application to the facts presented here. That case dealt with a tape recorder that was installed by an employer to make audio recordings of its employees, but the recorder in fact failed to record audio. On that basis, the court held that because the conversation was not actually recorded, there was no collection as understood by PIPEDA in that case. However, neither the Federal Court or Federal Court of Appeal stated that personal information must, in all cases, be recorded in order to constitute a collection under PIPEDA or other private-sector privacy legislation. Furthermore, as our investigation has established, the AVA technology did in fact “record”, and in our view collect, personal information in the form of images and biometrics.

- We accept that the demographic output generated by the AVA technology, such as age and gender assessments, would not, on their own, constitute personal information for the purposes of the Acts. That said, non-identifying information can be “personal information” in context,Footnote 35 and in this case, the demographic output was retained with other information including unique biometric information, location, and a timestamp. It is our view that the combination of this information raises a likelihood, beyond a “serious possibility”, that the individual could be identified. This is the case even though we found no evidence that CFCL attempted to identify individuals from this collected personal information. It is therefore our position that the demographic output also constitutes personal information in this context.

- As such, we cannot accept the conclusions from the Third-Party Report that the “stored gender and coarse age estimates generated by the system are anonymous”. The methodology of that report was limited and failed to take into account the extensive information that had been collected and generated by CFCL, which we were able to obtain in the course of our investigation.

- Finally, we are of the view that the collection of video and audio recordings during the calibration and testing period also constitutes a collection of personal information pursuant to the Acts.

Was there Valid Consent and Notice?

- CFCL did not ensure valid consent and notice, for its collection and use of personal information via the AVA software, as detailed above. In coming to this determination, our Offices considered: (i) the appropriate form of consent for CFCL’s practice; (ii) the meaningfulness of consent in the context at hand; and (iii) the adequacy of the notice provided by CFCL for the purposes of PIPEDA, PIPA AB and PIPA BC.

- Principle 4.3 of Schedule 1 of PIPEDA states that the knowledge and consent of the individual is required for the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information, unless these requirements are specifically exempted under section 7 of PIPEDA. Principle 4.3.4 further provides that the form of the consent sought by the organization may vary, depending upon the circumstances and the type of information. In determining the form of consent to use, organizations shall take into account the sensitivity of the information. Although some information (for example, medical records and income records) is almost always considered to be sensitive, any information can be sensitive, depending on the context. Principle 4.3.5 provides, in part, that in obtaining consent, the reasonable expectations of the individual are also relevant. Finally, Principle 4.3.6 states that the way in which an organization seeks consent may vary, depending on the circumstances and the type of information collected. An organization should generally seek express consent when the information is likely to be considered sensitive.

- Similarly, section 7(1) of PIPA AB requires the consent of the individual for the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information, except where the Act specifies. Section 8 of PIPA AB sets out the various forms of consent, which include the following three possibilities:

- express oral or written consent;

- deemed consent where it is reasonable that an individual would voluntarily provide the information for a particular purpose; and

- ‘opt-out’ consent where the organization must provide easy-to-understand notice to the individual of the particular purposes of the collection, use or disclosure, the individual has a reasonable opportunity to decline or object, and opt-out consent is appropriate for the level of sensitivity of the personal information involved.

- PIPA BC contains similar requirements to the above. In line with section 6 of PIPA BC, consent for the collection, use or disclosure of personal information is required unless an exemption is specifically authorized by the Act. Subsection 7(1) of PIPA BC states that an individual has not consented unless they have been given notice. In consideration of express versus implied consent, section 8(1) of PIPA BC sets out the criteria under which deemed consent for the collection, use or disclosure of personal information is applicable.

- The Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consentFootnote 36 (the “Guidelines”) jointly issued by the OPC, OIPC AB and OIPC BC provide that “organizations must generally obtain express consent” when: (i) the information being collected, used or disclosed is sensitive; (ii) the collection, use or disclosure is outside of the reasonable expectations of the individual; and/or (iii) the collection, use or disclosure creates a meaningful residual risk of significant harm. This is reinforced by a decision made by the Supreme Court of Canada.Footnote 37

- In our view, biometric information is sensitive in almost all circumstances. It is intrinsically, and in most instances permanently, linked to the individual. It is distinctive, stable over time, difficult to change and largely unique to the individual. Within the category of biometric information, there are degrees of sensitivity. Facial biometric information is more sensitive since possession of a facial recognition template can allow for identification of an individual through comparison against a vast array of images readily available on the internet or via surreptitious surveillance.

- Furthermore, mall visitors would not, in our view, reasonably expect CFCL’s collection and use of their biometric information. In fact, a visitor would have no reason to expect that their image was being collected by an inconspicuous camera while searching a mall directory. Nor would such an individual expect that this image would be used to create a biometric representation in support of CFCL’s commercial analytics.

- As such, in order to comply with the Acts, and conduct its practices in accordance with the Guidelines as reinforced by the Supreme Court of Canada, CFCL should have obtained express opt-in consent. That consent should have been obtained at the time of the visitor’s engagement with the map, before CFCL captured and processed their image via the AVA technology.

- Secondly, we cannot accept CFCL’s reference to its Privacy Policy as supporting meaningful consent to the collection and use of personal information via the AVA technology, whether for the video and audio recordings collected and used for calibration and testing, or for the subsequent collection and use primarily at issue.

- Principle 4.3.2 of Schedule 1 of PIPEDA provides that an organization must make a reasonable effort to ensure that the individual is advised of the purposes for which the information will be used and to make the consent meaningful, the purposes must be stated in such a manner that the individual can reasonably understand how the information will be used or disclosed. In addition, section 6.1 of PIPEDA requires that for consent to be valid, it must be reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use, or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting.

- Section 13(1) of PIPA AB requires that before or at the time of collecting the individual’s personal information from the individual, the organization must notify the individual in writing or orally of the purposes for which the information is collected. The notice must also include the name, position, or title of a person who is able to answer on behalf of the organization the individual’s questions about the collection.

- Section 10(1) of PIPA BC requires that on or before collecting personal information about an individual from the individual, an organization must disclose to the individual verbally or in writing the purposes for the collection of the information. The organization must, upon request, also provide the position name or title and the contact information for an officer or employee of the organization who is able to answer the individual's questions about the collection.

- Additionally, the Guidelines provide that individuals should be made aware of all purposes for which information is collected, used or disclosed. These purposes must be described in meaningful language, avoiding vagueness like ‘service improvement’, and should not be buried in a Privacy Policy or terms of use as it serves no practical purpose to individuals with limited time and energy to devote to reviewing privacy information. [emphasis added]

- In this case, individuals would not have understood the nature of the practices in question as they had not been notified, and were otherwise unaware, that CFCL was using the AVA technology. While CFCL’s Privacy Policy states that some of its properties are equipped with cameras that it uses to “monitor foot traffic patterns and [that may] assist [CFCL] in predicting demographic information” about mall visitors, and that personal information may be collected for the purpose of “researching, developing new products and techniques to improve its services”, these statements would not have allowed those mall visitors to reasonably understand that while they were using a mall directory: (i) close-range video and audio recordings were being taken of them during the testing and calibration period; and/or (ii) that their faces were being detected, captured in the form of digital images, and turned into numerical representations by facial recognition software for the purposes of predicting demographic information about them, such as their age range and gender. We also note that this information is embedded approximately 2,300 words into a 5,000-word Privacy Policy, which many users will never read before their image is captured.

- Similarly, CFCL could not rely on the decals installed on mall entrances as sufficient to ensure adequate consent under PIPEDA; nor do they constitute adequate notice under PIPA AB or PIPA BC. As shown at paragraph 59 of this report, the decal only mentions that video recordings are for visitor “safety and security”, and does not indicate any other purposes, such as those associated with CFCL’s use of the AVA technology. Further, the link provided is a link to CFCL’s website homepage, not the actual Privacy Policy. There is no indication that video recordings or cameras are used for any purpose other than “safety and security”, and the wayfinding cameras are inconspicuous in comparison to the more obvious security cameras, such that there is no evident reason or prompt for visitors to search out further information about further uses in a privacy policy. These other uses, which are of a less intuitive and more questionable nature, are in fact conspicuous in their absence from the signage.

- Moreover, the Guidelines provide that in order for consent to be considered valid, or meaningful, organizations must inform individuals of their privacy practices in a comprehensive and understandable manner. This means that organizations must provide information about their privacy management practices in a form that is readily accessible [emphasis added]. We note that CFCL’s wayfinding directories are physical locations, while their referenced Privacy Policy is available on their website, or at Guest Services elsewhere in the mall. Thus, the Privacy Policy is not readily accessible to individuals while they are engaging with a wayfinding map.

- Furthermore, given that mall visitors would be unaware of the AVA technology, or even alerted that video recordings may be used for purposes beyond safety and security, they would have no reason to seek out the Privacy Policy to obtain further information, and it would not be intuitive for them to seek out an online policy to understand privacy practices in a physical shopping environment.

- We further note that with regard to the accessibility of CFCL’s Privacy Policy, we attempted, in the course of the investigation, to obtain a copy of CFCL’s Privacy Policy at its Toronto Eaton Centre’s Guest Service Desk. We noted that the employee seemed confused about the request, and indicated that they did not have a copy of the Privacy Policy. It was only after returning a second time, and additional prompting, that the employee offered to print a copy of the Privacy Policy, which in fact, turned out to be CFCL’s “privacy statement” as opposed to the entirety of the policy.

- To conclude on the question of meaningfulness, it is our view that for the consent to have been meaningful, it should have been supported by a clear and conspicuous explanation of the purposes for which CFCL would capture and use individuals’ personal information, as well as what information would be collected and how it would be used. CFCL provided no such explanation to wayfinding directory users and did not obtain meaningful consent for its AVA practices.

Was Personal Information Retained appropriately?

- As noted in paragraph 52 of this report, during the course of the investigation, our Offices discovered that Mappedin retained, on CFCL’s behalf, 5,061,324 numerical representations of faces and associated information. Given that no purpose for such retention could be identified or explained, our Offices made the decision to expand the scope of the investigation to consider whether CFCL met its obligations pursuant to the provisions of the Acts pertaining to the retention of personal information.

- As previously established, our Offices consider these numerical representations and associated information to be personal information within the meaning of the Acts. We note that principle 4.5.3 of PIPEDA, section 35 of PIPA AB and section 35 of PIPA BC all set out requirements to destroy or depersonalize any personal information when it is no longer needed to fulfill the identified purpose of its collection, or in the case of PIPA BC, one year subsequent to being used to make a decision. We note that when asked, Mappedin could not articulate any purpose for the collection or retention of this information on behalf of CFCL. As such, in addition to the fact that CFCL did not obtain valid consent to collect the original images, CFCL and MappedIn had no identified reason to retain these numerical representations, beyond the very brief period necessary for the AVA software to process the images. While we acknowledge Mappedin’s claim that the server containing the information had been “decommissioned”, this did not in our opinion, meet the requirements of the Acts, as the server was readily re-activated with all personal information accessible. In fact, we have found in breach investigationsFootnote 38 that legacy systems and “decommissioned” data, if not deleted, can quickly find their way into nefarious hands should a cyber attack occur.

- Consequently, we find that CFCL contravened: principle 4.5.3 of Schedule 1 of PIPEDA; section 35 of PIPA AB; and section 35 of PIPA BC.

Recommendations

- In our preliminary report, we recommended that if CFCL decides to pursue the use of the AVA technology in its shopping malls, it should obtain express opt-in consent, in accordance with the Acts and consistent with the Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent. CFCL could, for example, undertake to implement changes to the way visitors interact with wayfinding directories by prompting a message box on the screen as soon as one or more faces are detected. The message should explain, in a simple and comprehensible way, the privacy implications associated with the AVA technology – including the collection and use of biometric information. Users should have the option to opt-in or refuse to provide consent, and should not be required to consent, as a condition to being able to use the wayfinding directory.

- Alternatively, we recommended that CFCL cease the use of the AVA technology.

- In addition to the above, our Offices recommended that CFCL ensure that all facial arrays (i.e., numerical representations) and associated information are deleted, as they were collected without consent and retained for no discernable purpose.

- Finally, our Offices recommended that CFCL ensure that frontline staff are trained and kept apprised of their obligation to provide the entirety of the Privacy Policy upon request at service desks.

CFCL’s Response to our Recommendations

Consent

- CFCL expressly disagreed with our findings. Nevertheless, it confirmed that it had disabled its AVA software on July 31, 2018 and subsequently removed the technology from its wayfinding kiosks, and that it had no current plans to reinstall the technology.

- CFCL also agreed to engage front-line staff in a training program that would help ensure that they are kept apprised of their obligation to provide the entirety of the Privacy Policy upon request at service desks. CFCL advised that this training was completed on July 30th 2020, and that yearly refresher training would be provided.

- We noted that CFCL’s commitments did not preclude the possibility of reimplementing its AVA program in future. We therefore asked CFCL to confirm that should it do so, it would obtain consent consistent with our Offices’ recommendation, as outlined in paragraph 96 above.

- CFCL responded that if in the future it were to pursue the use of the AVA technology in its shopping malls, it would obtain “adequate consent, in accordance with the applicable privacy legislation and consistent with the Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent”.

- CFCL refused, however, to commit to obtaining consent consistent with our recommendations (i.e., to obtain express opt-in consent), asserting that our recommendation was speculative.

Retention

- CFCL has confirmed to us that it has deleted the numerical representations and associated information and any calibration videos in its custody or under its control that are no longer necessary for legal purposes, and that no such data will be retained by CFCL or Mapped in for any other purpose. We therefore consider this aspect of the matter resolved.

Conclusion

- To conclude, we find that CFCL engaged in the collection and use of personal information through the deployment of the AVA technology in its shopping malls without ensuring knowledge, consent or notice.

- Consequently, we find that CFCL contravened: principles 4.3 of Schedule 1, as well as section 6.1, of PIPEDA; section 7(1) and section 13(1) of PIPA AB; and sections 6 and 10(1) of PIPA BC.

- Additionally, we determined that CFCL failed to ensure the timely disposal of personal information in the form of numerical representations of faces – and related information – collected through the deployment of the AVA technology in its shopping malls.

- Based on CFCL’s commitments and facts outlined above, we accept that CFCL is currently in compliance with the Acts. We therefore consider this matter to be well-founded and resolved.

- That said, we wish to remind CFCL that regardless of whether it disagrees with our Office’s findings, we expect that, should it implement AVA technology in its malls in future, it will do so in a manner that respects Canadian privacy laws, as reflected in our recommendations.

Issue 2: Whether CFCL’s use of mobile device geolocation technologies resulted in the collection, use and/or disclosure of personal information, and if yes, whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for that collection, use and/or disclosure?

CFCL’s Representations and our Investigation

- During our investigation, we asked CFCL how geolocation and MAC addresses were used, alone or in combination with other information, in order to determine whether CFCL had collected or used personal information in the context. In addition, we asked questions to determine whether CFCL obtained adequate consent for the collection and use of personal information, where required.

- In order to corroborate the information provided to us, and better understand the practices at issue, we also sought representations from Aislelabs, a third-party service provider under contract with CFCL.

Overview of CFCL’s Geolocation Implementation

- CFCL established and maintains Wi-Fi networks at all of its retail properties in order to offer complimentary internet access to mall visitors.Footnote 39 When a visitor with a Wi-Fi enabled device enters one of CFCL’s properties, their device will be detected by a wireless access point. During communication with the access point, information is collected from the visitor’s device – including its geolocation, which can be defined as information allowing for the estimation of a physical location. In other words, CFCL utilizes Wi-Fi triangulation, using signals sent from visitors’ devices, to calculate their approximate position. If the visitor chooses to connect to the Wi-Fi network, they must log in and provide additional information. CFCL contracted with a third party company, Aislelabs, to analyze the information collected via its Wi-Fi access points on its behalf.

- CFCL described two processes by which it collects information from Wi-Fi enabled devices: (i) “Anonymous Shopper Journey”; and (ii) “Logged In Shopper Journey”.

- "Anonymous Shopper Journey": When an individual with a Wi-Fi enabled device enters a CFCL property, their MAC address is detected, and used to create a randomized unique identifier as described at paragraphs 126 and 127. If the individual does not log in, then this unique identifier and associated geolocation information is the extent of the information collected.

- "Logged In Shopper Journey”: If an individual chooses to log in to CFCL’s Wi-Fi network with a mobile device, the device’s MAC address is detected and collected as described above, and the individual is required to agree to CFCL’s Terms and Conditions and to provide additional personal information, such as full name and email address, in exchange for access.

- According to its submissions, CFCL employs geolocation technologies at all 19 of its retail properties in Canada,Footnote 40 these being:

Property Province CF Market Mall Alberta CF Chinook Centre Alberta CF Richmond Centre British Columbia CF Pacific Centre British Columbia CF Polo Park Manitoba CF Champlain New Brunswick CF Toronto Eaton Centre Ontario CF Sherway Gardens Ontario CF Lime Ridge Ontario CF Fairview Mall Ontario CF Markville Mall Ontario CF Shops at Don Mills Ontario CF Fairview Park Ontario CF Masonville Place Ontario CF Rideau Centre Ontario CF Galeries d’Anjou Quebec CF Carrefour Laval Quebec CF Promenades St-Bruno Quebec CF Fairview Pointe Claire Quebec - When we asked CFCL to explain the purposes for its deployment of the geolocation technologies, it represented that it is for “counting pedestrian traffic and obtaining rough user segmentation to support CF in managing pedestrian flow, and to establish the value of its properties to advertisers and merchants”. In addition, CFCL uses what it described as anonymous, aggregate information to research and develop new products and techniques to improve its services for consumers and retailers.

- CFCL stated that it did not employ geolocation “tracking” in its shopping malls, and instead indicated that the technologies it employs simply locate mobile devices to a general area or zone in its properties. CFCL took the view that it does not identify or track individuals, but mobile devices.

- Information provided by Aislelabs indicated that their indoor geolocation capabilities are based on a Wi-Fi positioning system that can triangulate the location of devices to an area referred to as a “zone”. It represented that each CFCL property consists of multiple zones. For example, the Eaton Centre was described as having 29 zones. Each zone was characterized as having several retail outlets.

Further information regarding Aislelabs

- Aislelabs describes itselfFootnote 41 as a technology company that offers Wi-Fi location marketing and advertising, as well as an analytics platform. For CFCL, it also builds audience profiles for visitors, complete with their behavior, interests and demographics based on information collected via the Logged In Shopper Journey.

- We note that although CFCL indicated that it does not store the information collected by Aislelabs on its behalf, the service agreement between the two parties stipulates that CFCL remains the owner of the information collected by the geolocation technologies:

Aislelabs acknowledges that it obtains no ownership nor proprietary rights of any nature or kind in or to the Content or Your Data or any part thereof under the terms of this Agreement. All right, title and interest in and to the foregoing (including any and all related Intellectual Property Rights, modifications and additions) thereto shall at all times remain with You.

- Based on the terms of this contractual agreement, we understand that CFCL remains responsible for information collected by Aislelabs on CFCL’s behalf.

- In their representations, Aislelabs confirmed that it does not use the information obtained in the context of their agreement with CFCL for any purposes other than to provide the contracted service. It was further stated that Aislelabs does not share any such information with third parties.

Anonymous Shopper Journey

- According to the information provided by CFCL, when a Wi-Fi-enabled mobile device enters one of its properties, the MAC address of the device is detected and collected, enabling Aislelabs’ software to differentiate between first time and repeat visitors, calculate the approximate location of a device inside CFCL’s properties via heat maps, and capture walking paths and “dwell time”.

- Aislelabs, which collects and analyzes the information on behalf of CFCL, provides the latter with aggregated reports based on the collected information, which includes for example, statistics about the number of shoppers, repeat customers, time spent in a zone within a mall, top walking paths and heat maps representing shopper density within designated zones. CFCL is able to access those reports via a web-based dashboard.

- Both CFCL and Aislelabs represented that this process is “anonymous” because Aislelabs’ software uses a technique called hashing, which consists of using a one-way function to assign a unique identifier to the mobile device in lieu of the actual MAC address. This process is completed before the identifier is saved onto Aislelabs’ database. Hashing a unique identifier offers protection against reverse engineering (or other means aimed at recovering the original value) both by the organization collecting and holding the information and by third parties. While it is theoretically possible to reverse a securely hashed value, it is highly impractical. Our Technological Analysts confirmed that based on Aislelabs’ representations, they are using an algorithm currently accepted as cryptographically secure.

- In addition to hashing the MAC addresses, Aislelabs represented that it further replaces each hashed MAC address with a random identifier, so that the hashed MAC addresses cannot be obtained from the value stored on its database. Therefore, outside of Aislelabs systems, the resulting random identifier cannot be linked to the original MAC address, providing an additional layer of depersonalization. This additional step further mitigates the risk of the original MAC address being recovered and associated to the geolocation data, by CFCL, Aislelabs or any unauthorized third party.

Logged In Shopper Journey

- The Logged In Shopper Journey also relies on the collection of MAC addresses, which are subsequently hashed, but CFCL advised that it collects additional personal information, with consent, when a mobile device is used to connect to its complimentary Wi-Fi service. Access to CFCL’s Wi-Fi requires that the visitor sign up for an account. Accordingly, CFCL collects additional information via the account creation process, such as first and last name, email address, and language preference.

- CFCL represented that MAC addresses and geolocation information collected in the Anonymous Shopper Journey “are not, and cannot, be subsequently associated with the Logged In Shopper Journey”. As such, at the time of account creation, no information is associated from previous visits made by the individual. Additionally, if a Wi-Fi user who has logged out of their account subsequently visits a CFCL property without signing in, MAC address and geolocation data will only be collected in the form of the Anonymous Shopper Journey. Information collected during the visit will only be associated to the visitor’s account if they are logged in. CFCL further asserted that the information stored in the two solutions cannot be combined in any way.

- CFCL represented that it obtains express consent for this practice via the Terms & Conditions accessible from the login page, which incorporate the Privacy Policy explaining the practices in question.

- More specifically, according to CFCL, when a visitor wishes to use CFCL’s complimentary Wi-Fi service, they must log in using one of various available methods (i.e.: a social media account or email address), after agreeing to its Terms and Conditions (“T&C” or the “Terms”). The Terms shown on the Wi-Fi login contain the following:

By accessing The Cadillac Fairview Corporation Limited’s Wireless Internet Service you agree to comply with the Terms of Service. If you do not accept the Terms, do not access or use the Service. The following summary of the Terms is provided for your convenience. Please read the full Terms of Service below.

Summary

- You will act lawfully, responsibly and reasonably while using the Service.

- You assume full responsibility for your use of third party websites while using the Service.

- Under no circumstances will Cadillac Fairview be liable as a result of your use or inability to use the Service.

- You agree to indemnify and hold harmless Cadillac Fairview from any all claims, relating to or arising out of your use of the Service.

- There is no guarantee of the privacy or security of any transmission made or received through the Service.

- As a complimentary Service, it is provided without any warranties. Cadillac Fairview does not warrant the availability or reliability of the Service.

- Cadillac Fairview reserves the right to block certain internet websites or services, and may revoke your access to the Service at any time.

- Cadillac Fairview may monitor your activity in connection to the Service and may disclose any information related to, as necessary.

- Personal information will be used as set forth in our Privacy Policy [emphasis added]

- The Service and the Terms may change without notice. You should check back to see the Terms in effect. Your continued use of the Service will constitute your acceptance of the Terms.

Click here to accept and continue to the Wi-Fi.

Click here to read the full Terms and Conditions.

- As highlighted in the above excerpt, the summary says that “Personal information will be used as set forth in our Privacy Policy”, with an embedded link. We note that this link is actually not a link to CFCL’s Privacy Policy, but instead takes individuals to a page titled “CF SHOP! Privacy Statement”. Individuals must scroll to the bottom of the page to view the link to CFCL’s actual Privacy Policy.

- CFCL asserted that when an individual accepts the Wi-Fi Terms, the device user provides their consent to CFCL’s collection and use of their personal information, and that since “Wi-Fi Terms and Conditions expressly reference the Privacy Policy, [they] incorporate it”. Should individuals choose not to accept the Terms, they would be denied use of the complimentary Wi-Fi service. While the summary does highlight provisions relating to limiting CFCL’s liability, and appropriate use of the Wi-Fi service, there is no specific mention of privacy practices, beyond a link to the CF SHOP! Privacy Statement.

- In the full T&C document, CFCL informs users of the Wi-Fi Service (the “Service”) that it may monitor, log and review users’ activities in connection with their use of the Service. Further, it states that “[a]ny personal information you supply to us for the purposes of accessing the Service will be used as set forth in our Privacy Policy, which can be found at http://cfshop.ca/privacy.html and these Terms”.

- Specifically, CFCL pointed to certain sections of the Privacy Policy, including, under the section “Browser and Device Information”