Canadian adware developer Wajam Internet Technologies Inc. breaches multiple provisions of PIPEDA

PIPEDA Report of Findings #2017-002

August 17, 2017

Complaint under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (the “Act”)

Executive Summary

- On June 12, 2016, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada initiated a complaint against Wajam Internet Technologies Inc. (the "respondent") under subsection 11(2) of the Act.

- The respondent is the developer of software known as “Wajam” or “Social2Search” (“the software”). Once installed on an individual’s computer, the software is designed to track the individual’s online search queries and to overlay, onto existing search engine results, search results derived from content shared by an individual’s “friends” and others known to the individual on social media. The software also displays ads based on the individual’s online search queries. It is distributed and installed primarily via third party distributors that bundle the software as an add-on to other unrelated software that individuals can download.

- The Commissioner opened the complaint having reasonable grounds to investigate the following matters with respect to compliance with the Act:

- whether the respondent was obtaining meaningful consent from individuals to the installation of its software;

- whether the respondent was not permitting users to withdraw consent to the ongoing collection, use and disclosure of their personal information, by making it difficult to delete its software; and

- whether the respondent was not adequately safeguarding users' personal information, by, for instance, uploading user information to its servers in plain-text form and through unencrypted channels.

- The respondent was notified of the complaint by our Office on September 6, 2016.

- In examining the respondent’s privacy practices, we: (i) analyzed representations and documents received from the respondent between October 7, 2016 and July 11, 2017; (ii) conducted technical testing of the software by creating our own "dummy" user accounts; and (iii) conducted a site visit at the respondent's head office on January 18 and 19, 2017.

- The results of our investigation lead us to conclude that the respondent did not have a privacy accountability framework in place and was, therefore, unable to provide evidence to demonstrate that it had policies and procedures in place to give effect to its obligations under the Act.

- Our investigation revealed that the respondent’s practices resulted in the installation of the software and the collection and use of personal information without meaningful consent, as required under the Act. Given that the software comes bundled as an unsolicited add-on with other unrelated software and that it results in the collection and use of individuals’ search queries upon installation, we expected that the installation process and consent screens presented to individuals would be extremely clear and transparent.

- However, our investigation revealed failings regarding the installation methods and consent screens used by the third party distributors of the software. These problems included the silent installation of the software by certain distributors, contrary to the terms of the respondent's Distribution Agreement (the “Agreement”) and Distribution Guidelines (the “Guidelines”). They also included problems with the consent screens displayed during installation of the software, including problems with “decline” buttons, confusing options during the installation process, missing or outdated text in consent screens and the use of consent screens that had not been authorized by the respondent. We also discovered problems with multiple offer consent screens which did not clearly present information to individuals regarding the software. While the respondent took certain limited steps to monitor and enforce its contractual agreements with distributors, these steps did not sufficiently protect against the software being installed without consent.

- Our investigation revealed concerns with outdated (and as a consequence misleading) information on the Wajam and Social2Search websites regarding the functionality of the software, and inaccurate and incomplete information about the collection, use, safeguarding and retention of personal information in its Privacy Policy.

- In addition, we noted barriers encountered by certain users and in our own testing when attempting to uninstall the software, which resulted in the continued collection of personal information and the retention of unique user identifiers on users' computers and devices even after the software was supposed to have been uninstalled.

- During uninstallation, our user accounts were periodically presented with unsolicited ads, potentially unwanted programs, or directed to fake software, on the Wajam uninstall landing page. The ads and programs were served through a third-party ad network. Our investigation revealed that the respondent's source code called-up the ad network to issue this material. Where a user clicked on an ad and/or installed such programs, third-parties could potentially collect user personal information through malicious means and without consent. While the respondent did not deny such activity happened, it denied prior knowledge of it and of the particular ad network and agreed to immediately disable the code responsible. If true, from a security monitoring perspective, it is highly troubling that the respondent did not have prior knowledge of this coding and the ad network within its own website and uninstallation workflow.

- We also found that all original, “raw”Footnote 1, data collected from users by the respondent and held within its primary database was being kept in unencrypted form, even though this data contained substantial volumes of personal information that was attributable to specific users.

- In addition, the respondent informed us that the raw user data held within its primary database was retained on an indefinite basis, even after users had uninstalled the respondent's software.

- Our Office issued a Preliminary Report of Investigation (the “preliminary report”) to the respondent on June 19, 2017. The preliminary report identified several contraventions of the Act by the respondent, as they pertain to the accountability, consent, limiting retention, safeguards and openness principles and made twelve recommendations to bring the respondent back into compliance with the Act.Footnote 2

- During the course of our investigation, the respondent indicated its intention to discontinue its operations and to sell its assets, including the software, to a recently-created company based in Hong Kong, called Iron Mountain Technology Limited ("IMTL"). In addition, the respondent indicated that the software would no longer be distributed in Canada, although it would continue to be distributed by IMTL in other countries.

- In response to the preliminary report, the respondent indicated that the sale of its assets to IMTL was complete and it no longer had an interest in, or control over, IMTL. As such, it stated that it was no longer accountable for IMTL’s practices under the Act. The respondent argued that it was, therefore, not in a position to be able to comply with the OPC's recommendations.

- Wajam agreed to the secure destruction of its hard drives, including all personal information of users remaining within its possession. We expect this destruction to be executed forthwith, with Wajam notifying us upon completion.

- Given the transfer of ownership to IMTL and the respondent’s inability to implement our recommendations, we conclude that the accountability, consent, limiting retention, safeguards and openness matters examined during our investigation are well-founded.

Summary of investigation

The respondent and its software:

- The respondent is a federally incorporated company with its head office located in Montreal. Prior to the transfer to IMTL, the respondent's core product was a social searchFootnote 3 engine application called "Wajam" or “Social2Search”.Footnote 4 Wajam was launched in October 2011 and Social2Search in May 2016. Although they have distinct websites, logos and brands, both Wajam and Social2Search operate in effectively the same manner and for the purposes of this report are treated as the same software, unless otherwise noted.

- At the time our investigation was initiated, Wajam was no longer being distributed, although it still functioned on computers on which it was previously installed and the Wajam website (wajam.com) continued to promote Wajam. The respondent indicated that Social2Search continued to be distributed in 40 different countries via third party distributors.

- Now owned by IMTL, the software operates using Internet browsers such as Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and Microsoft Edge. The software is installed via plug-ins, browser extensions and other techniques.

- The software is designed to capture a user's Internet communications, and in particular online search and shopping queries and social media content. The software interacts with, modifies and injects content into these communications. In particular, the software captures the keywords of a user's search engine and shopping website searches. It then routes them through the software's servers and, if the user has chosen to link their Wajam or Social2Search account to his/her social media accounts, the software is designed to append search results derived from content shared by a user's "friends" and others known to the user on social networks.

- The Wajam and Social2Search websites claimed that the software shares social network content to ease and better validate Internet searching:

"Social2Search is a social search engine that gives you access to the knowledge of your friends…When you search, you get a personalized layer of your friends' comments, likes and recommendations.

The browser extension lets you bring social search with you everywhere you browse the web. Search in places like Google, Bing, Yahoo!, Amazon, Yelp, Trip Advisor, YouTube and Ebay, and get recommendations from your friends without having to change your search behavior."Footnote 5

- In order for the software to be able to access a user’s social media, a user must take the additional step after the software has been installed of linking their social media accounts to the software. According to Wajam and Social2Search’s websites, users can log-in to the software using their Twitter or Facebook accounts. Once users have logged-in, the websites indicate that users can add Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn and Facebook as "friend" sources of social media content.

- Once installed and linked to a user’s social media accounts, the respondent claimed that when an individual searches in Amazon, Bing, Expedia, Facebook, Google, Instagram, Kijiji, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Tumblr, Twitter, YouTube or other “supported” websites (89 in total), the software will place the most relevant results from the social networks at the top of the user's search results, based on the search keywords used. The user will apparently see information about which friend shared the item, comments made about it and other friends who also shared that piece of content (see fig. 1):

Fig. 1: Wajam search results with social network “friends” content resulting from a Google search.

Fig. 1: Wajam search results with social network “friends” content resulting from a Google search.Text version

Screen capture of a Google engine search, with Wajam search results appearing at the top of the page directly above the Google search results on the same subject.

The Wajam search results show information relating to the user’s social network "friends", including which friend shared the item, comments made about it and other friends who also shared the content.

- However, during our investigation it became apparent that the information on the Wajam and Social2Search websites regarding the software’s functionality was outdated and inaccurate and had been for some time. Notwithstanding the claims on the websites, the respondent informed us that the ability to link to Google+ was removed in 2012, to LinkedIn in 2013 and to Facebook in 2014. Finally, the respondent indicated that the software’s integration with Twitter ceased in January 2017. As a result, at the time our investigation was initiated, the software was only available for use with Twitter and was no longer able to link to or search any of the other social media sources listed on the Wajam and Social2Search websites.

- The respondent confirmed that it generated revenue predominantly through the display of contextual advertisingFootnote 6 to individuals who had installed its software.

- The ads served to users may be:

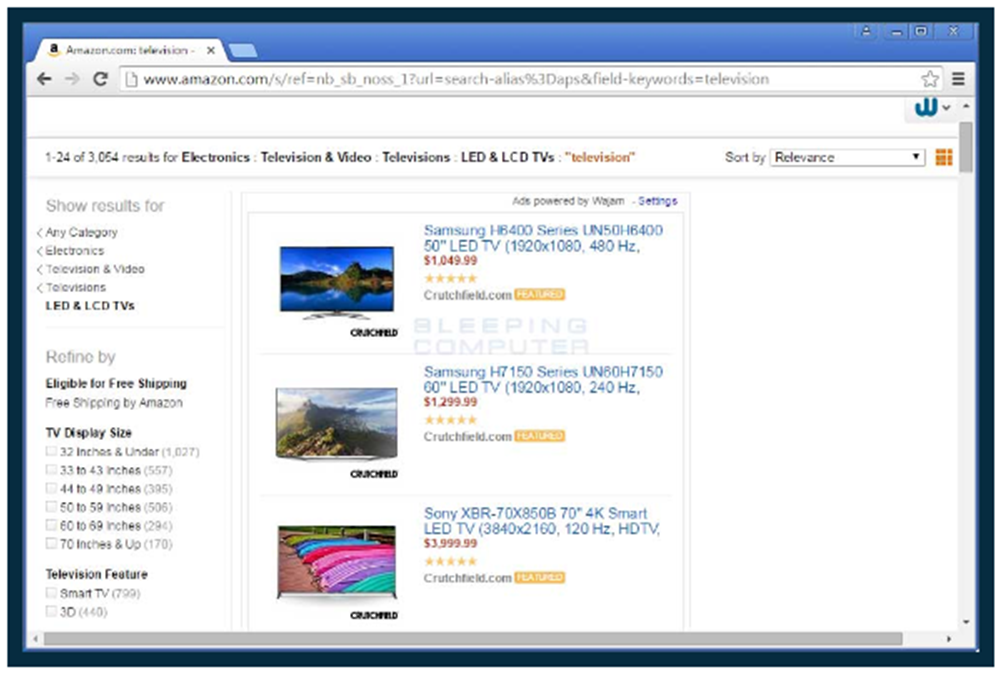

- based on a user's Internet search engine or online shopping site query in real time (or if there is no ad available for a query, an ad may be served for a historical search query). The ads are placed above or beside the search results and are labeled "Wajam Ads" or "Social2Search Ads” in respect of search engine queries and “Ads powered by Wajam” or “Ads powered by Social2Search” for shopping site queries (see fig. 2 below); and

- banner ads or in-image ads placed on other content websites being viewed by a user. The ads are based on the website category, e.g. sports, entertainment, news, etc. and not the user's search queries. These are labeled as "Ads by Wajam" or "Ads by Social2Search".

Fig. 2: “Ads powered by Wajam” inserted into a search for LED and LCD televisions on the amazon.com website.

Fig. 2: “Ads powered by Wajam” inserted into a search for LED and LCD televisions on the amazon.com website.Text version

Screen capture showing search results for LED and LCD televisions on amazon.com, a shopping site. The featured televisions on the screen are within a box entitled “Ads powered by Wajam”.

- The software begins to collect and transmit personal information upon installation and displays ads once users navigate to a supported website. This occurs without requiring that the software be linked to a user’s social media accounts.

- With respect to the process, once installed, the software automatically detects when a user browses on one of the supported websites. The software collects the keywords entered by the user and submits these to the respondent’s servers. The keywords are used by the respondent to display contextual ads. This process does not require that an individual log into or create an account with the software or link the software to their social media accounts. In other words, once it has been installed on an individual’s computer, the software collects search queries, displays ads, and generates revenue for the respondent without any further action from the individual being required.

Distribution of the software

- Since 2011, the respondent distributed the software through third party distributors (“distributors”). These distributors "bundle" Social2Search (and previously Wajam) with free software downloaded by individuals from the distributors’ websites or independent free software websites. For instance, when an individual downloads and installs a free software product such as an anti-virus program, pdf converter, or media player from a free software website (the “primary software”), the installation program may unexpectedly request that the individual install a number of other additional and unrelated programs, including Social2Search.

- Distribution of the software by third-party distributors was governed by a Distribution Agreement signed with the respondent. The Agreement provided that the respondent will compensate the distributor for each unique user which installs the software. As such, distributors had a strong financial incentive to achieve as many installations of the software as possible. As of November 2016, the respondent had in place agreements with 19 distributors. In total, the respondent entered into agreements with over 50 different third party distributors between 2011 and 2016 for the purpose of distributing the software.

- Until late 2014, individuals could also directly download the software from the main www.wajam.com website. As noted further below, the respondent claims it was forced to remove its software from the Wajam website to ensure that the website would continue to appear in search engine results.

- The software distribution model adopted by the respondent appears to have been highly successful. The respondent indicated that there have been "hundreds of millions of installations" of the software to date. Approximately 1.0% of installations were by individuals located in Canada. The respondent stated that in the month of July 2016 alone, there were over 75,000 installations of the Social2Search software in Canada and in August 2016, over 50,000 installations.

Changes to the software and its distribution as a result of actions by others

- The respondent claimed that from 2014, it faced challenges from online platform providers and competing free software developers, which affected the accessibility of its websites and software. The respondent alleged that one major search engine blocked the Wajam software. The respondent claims that it had to remove its Wajam software from its website to allow the website itself to be searchable.

- The respondent also alleged that when anti-virus programs changed from being largely subscription-based software, to free software, they became competitors in the same distribution space and started to flag, block or otherwise disrupt its software.

- Our research identified IT blogs, articles and anti-virus programs that classified the Wajam and Social2Search software as AdwareFootnote 7 or Potentially Unwanted Programs ("PUPs")Footnote 8:

“Wajam is an adware program that tracks user's Internet browsing and generates online advertisements. Most common adware or potentially unwanted applications infiltrate users' Internet browsers through free software downloads. Internet users should know that nowadays most of the free software download websites are using download clients to manage their free software download process. Unfortunately, some of the mentioned download clients don't properly disclose the fact that advertised browser plug-ins or toolbars will be installed together with the free program that users have decided to download.”Footnote 9

“Wajam…is an adware program that injects advertisements onto web pages while browsing the web. When you browse the web while this adware is installed, Wajam will display intrusive and unwanted ads onto websites that make it difficult to read the content of the site. To make matters worse, you will also find that this adware will cause your computer to act more sluggish or for your web browser to freeze…These ads are aimed to promote the installation of additional questionable content including web browser toolbars, optimization utilities and other products, all so the Wajam publisher can generate click-per-view revenue.Footnote 10

- The respondent contested these characterizations of its software. It claimed that such IT blogs were not an authoritative source of information and were both unfair and biased. It asserted that some PC security websites targeting its software were designed to look as if they originated from independent experts, but were in fact used to generate revenue from readers downloading free anti-virus or anti-malware software on the sites. The respondent claimed that it issued cease and desist letters to several parties, contesting their views of its software. It provided a copy of one letter to our office.

- We reviewed the respondent's registration and use of Internet domains. Between 2007 and 2016, the respondent registered 234 domains. Of these, 4 were opened between 2007 and 2013 and 221 opened between 2014 and 2016 (with 9 domains undated). The respondent stated that it opened the new domains when its existing websites and software started to be blocked and damaged by competitors.

- During our investigation, we also noted frequent, sometimes daily, updates of its software. Certain releases were linked to software changes, security updates, or the fixing of bugs. However, the respondent stated that other versions were released to create new software “signatures”. As with the new domains, the respondent claimed that this helped the software avoid detection and damage by anti-virus programs and what it claimed were software competitors.

- Similarly, the respondent stated that it launched Social2Search because of changes to major web browsers which prevented it from continuing to allow Wajam to be installed as an executable file. To circumvent these restrictions, the respondent stated it created Social2Search and continued marketing Wajam as a browser extension only. Despite the fact that it seems to have been designed as a replacement to Wajam, the Social2Search website makes no reference to Wajam.

- Despite these efforts to detect and thwart the software's installation, the respondent has been successful in having the software installed millions of times, including by many thousands of Canadian users.

Changes in the respondent’s operations following notification of investigation

- In response to the notification of our investigation, the respondent asked its third party distributors to cease distribution of the software in Canada as an interim measure until the investigation was complete. Although these instructions to distributors were issued in September 2016, we were able to download the software from certain distributors during our testing in December 2016. However, we later confirmed that the software appeared to no longer be distributed as part of software bundles in Canada.

- Shortly after the investigation started, the software also ceased displaying ads (the respondent’s primary personal information monetization method) to all Canadian users. The respondent indicated that while it continued to collect information from Canadian users on whose computers the software was previously installed, it would no longer use the data for advertising or other purposes. It would also implement a process to ensure no data would be collected from Canadian users going forward.

- In December 2016, we were notified that the respondent's principal shareholders and directors had decided to cease the respondent's operations and find another company to purchase the respondent’s assets, including the software.

- On February 14, 2017, we were informed that the respondent’s assets, including the software, would be transferred to IMTL, a company based in Hong Kong. According to the respondent, IMTL agreed to purchase the Social2Search and Wajam intellectual property, source code, domain names, certificates, and all relevant contracts (including contracts associated with non-Canadian users of the products).

- The respondent stated that it would not be transferring any personal information of Canadian users to IMTL and that it understood that IMTL did not intend to promote the software to Canadians.

- Wajam explained, however, that it would be transferring limited information about non-Canadian users to IMTL. The transfer would be confined to an MD5 hash value for each user, each user's installation date, as well as aggregated, non-identifiable, level information. Wajam further clarified that the aggregated information was analytical data contained within its business intelligence database, such as ad performance information by date, affiliate, country, search engine or browser, e.g., the number of ads clicked per day or per country. Wajam confirmed that the information was not linked to any user IDs or other identifiable information about its users. The information would be transferred to IMTL via a Virtual Private Network in encrypted form.

- The respondent confirmed that all user personal information remaining in its possession would be securely held by a third party and then purged after the transfer of ownership was completed, subject to any retention requirements by our Office.

- Notwithstanding the formal transfer of ownership, which was ongoing during much of our investigation, it was unclear to us whether the two organizations were entirely separate entities. We noted that IMTL was incorporated in November 2016 while our investigation was ongoing and its sole director specializes in among other things, providing business relocation and corporate services to businesses wishing to establish a presence in Hong Kong. We also noted that IMTL was to pay consulting fees to former employees, consultants and a shareholder of the respondent. In addition, the purchase price for the respondent’s assets was to be paid out of the IMTL’s profits from the software and IMTL was to pay the respondent for transition services.

- We further noted that sometime between February and March 2017, the Wajam and Social2Search websites (wajam.com and social2search.com respectively) had changed to list IMTL as the copyright owner of the sites. Furthermore, the End User Licence Agreement (“EULA”) on the sites indicated IMTL as the company with whom users were contracting. The content of the websites, including the description of the software and how it operates, appeared to be unchanged.

- In response to our preliminary report, the respondent indicated none of the current or former owners of Wajam were a shareholder, director or officer of IMTL, the sale of its assets to IMTL was complete and a final invoice for transitional services had been issued. As such, the respondent stated it no longer had any interest in, or control over, IMTL. The respondent provided no further information about IMTL’s creation, where IMTL’s day-to-day operations would be based or who owned and/or had effective control of IMTL.

- Subsequent to the issue of our preliminary report, we re-examined the wajam.com and social2search.com websites. We noted that when accessed from Canada, the websites each displayed a single page stating that the software was no longer available. However, when we used a US IP address the full content of the websites was accessible.

Section 1 - Accountability:

- The respondent confirmed that it uses a privacy consultant in Israel, to act as its privacy officer and support compliance with its technical and privacy-related obligations. We interviewed the privacy officer via videoconference during our site visit.

- In a Questionnaire sent to TRUSTe in October 2015, the respondent claimed to have policies and procedures on: (i) the receipt and resolution of access requests; (ii) the accuracy and correction of personal information; (iii) compliance with the Information Privacy Principles; and (iv) the receipt, investigation and response to privacy-related complaints. However, apart from pointing to a Privacy Policy, the respondent was unable to provide any evidence to demonstrate that these privacy mechanisms and procedures existed or were followed.

- It also claimed that its employees consulted the privacy officer on a regular basis, in particular prior to any new product launches, and received informal privacy training. However, it was unable to produce copies of any privacy communications or training material transmitted to or from staff, except for a template of a "Data Privacy Table".

- We examined the template and noted that it was primarily for use in developing products. While it included a list of key privacy considerations and questions for employees, there was no supporting guidance on how to complete it or make use of it. The respondent acknowledged that the tables were not completed for the launch of its Wajam or Social2Search software.

- The respondent stated that its systems administration and business intelligence employees received extensive security training, which included protecting its systems and databases. We asked for copies of the material used. The respondent stated that such training was informal and it was unable to produce any documentation or evidence that it took place.

- We requested a copy of the respondent's data retention and destruction procedures and schedule. The respondent provided a checklist containing disposition rules on purging information in two of its four databases. However, employees were unable to explain why the dates cited in the rules had been set and confirmed that raw user data held in the respondent's primary database was in fact retained indefinitely. We were told that there was no overall data retention and destruction policy and procedure adopted.

Section 2 - Consent:

The installation process

- For Wajam or Social2Search to be installed via a distributor, an individual must first elect to download a piece of software (“the primary software”) with which Wajam or Social2Search has been bundled. In the examples we reviewed, individuals were not informed prior to selecting the primary software that it comes bundled with the option to install Wajam or Social2Search. In addition, the primary software is often unrelated to Wajam or Social2Search (e.g., a pdf converter or media player program). However, the respondent maintained that when installing the primary software individuals were presented with consent screens that informed users about Wajam or Social2Search and ensured that individuals give their informed consent for it to be installed.

- The respondent maintained that these consent screens were presented to users in one of two ways: (i) a single offer process, and (ii) a multiple offer process.

Single offer process

- The most common form of distribution for Wajam and Social2Search software by the respondent was the single offer process. This process requires an individual to first consent to install the free software they selected, and then consent to install each additional piece of unsolicited software (e.g. Wajam or Social2Search) within a bundle through a series of separate consent screens:

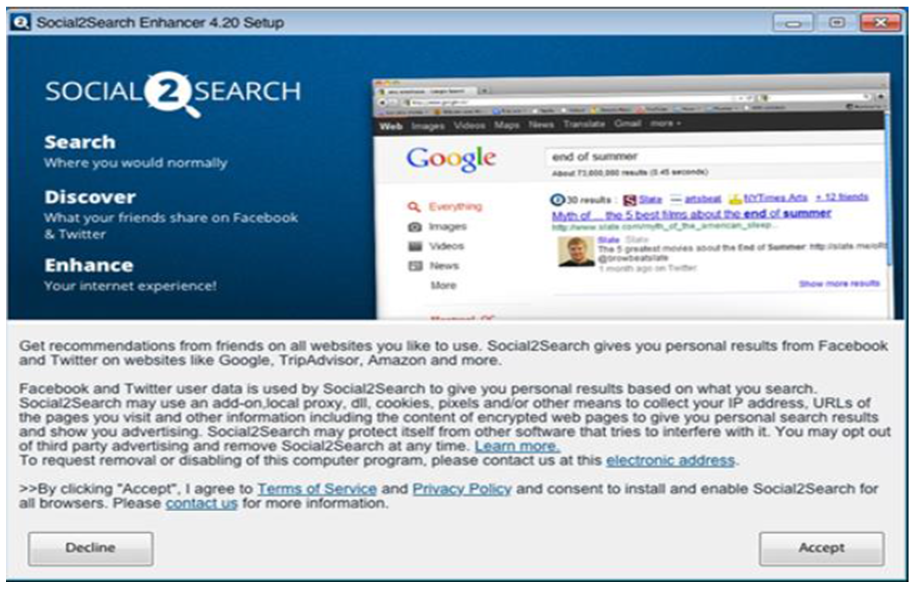

Primary software Social2Search Software C Software D… Consent screen Consent screen Consent screen Consent screen Accept/Decline Accept/Decline Accept/Decline Accept/Decline - The respondent provided us with copies of its standard image-based and text-based consent screens used in single offer processes (see fig. 3) and sent us examples of several image-based and text-based consent screens used by different distributors.

Fig 3: Example of standard Social2Search image-based, single-offer, consent screen.

Fig 3: Example of standard Social2Search image-based, single-offer, consent screen.Text version

Screen capture of a Social2Search consent screen. The first half of the screen capture promotes the Social2Search software alongside an image of a Google engine search. The second half of the screen contains consent text that reads as follows:

“Get recommendations from friends on all websites you like to use. Social2Search gives you personal results from Facebook and Twitter on websites like Google, TripAdvisor, Amazon and more. Facebook and Twitter user data is used by Social2Search to give you personal results based on what you search. Social2Search may use an add-on, local proxy, dll, cookies, pixels and/or other means to collect your IP address, URLs of the pages you visit and other information including the content of encrypted web pages to give you personal search results and show you advertising. Social2Search may protect itself from other software that tries to interfere with it. You may opt out of third party advertising and remove Social2Search at any time. Learn more. To request removal or disabling of this computer program, please contact us at this electronic address. By clicking accept, I agree to Terms of Service and Privacy Policy and consent to install and enable Social2Search for all browsers. Please contact us for more information”

The words “Learn more”, “electronic address”, “Terms of Service”, “Privacy Policy”, and “contact us” are hyperlinked.

The button on the bottom left of the screen says “decline”, while the button on the bottom right says “accept”. 3.

- Our testing found that some distributors whose installation bundles we examined displayed consent screens consistent with the versions provided by the respondent. The buttons and links, including those to the respondent’s Privacy Policy, worked as stated.

- However, our testing did identify concerns with certain distributors' consent screens:

- During the installation of one free software program, we were presented with a consent screen for Wajam containing outdated text from an August 2012 Wajam Privacy Policy. The respondent explained that this likely occurred as the distributor was offering an older version of the software;

- On installing another software program via the same distributor, there appeared to be a failure in the retrieval of the primary software, which led to confusing options being presented. When the installation failed, we were asked if we wanted to try the installation again. When we chose to "cancel", we were presented with an "Abort installation" box (see fig. 4). The first two options were greyed-out and appeared unavailable, but were in fact active options. Therefore, the only option that appeared to be available was the "Continue" button, which, when we clicked on it, resulted in Wajam being installed. We noted that the dialog boxes also obscured our view of the Wajam consent text.

Fig 4: Consent process seen on installing Pixel Degrees free software using Better Installer.

Fig 4: Consent process seen on installing Pixel Degrees free software using Better Installer.Text version

Screen capture shows an installation page for Pixel Degrees which contains consent text for the bundled Wajam software program. The installation page and consent text are in grey.

Superimposed over the page is a dialogue box entitled “Abort installation”. The dialogue box reads as follows:

“To cancel the installation click abort. To install without bundled offers click skip. Otherwise click continue to proceed.”

There is a checked checkbox that reads “resume download on next windows startup”.

There are three buttons at the bottom of the dialogue box. The left two buttons are in grey and read “abort” and “skip”. The button on the right is green and reads “continue”.

- In another case involving a different distributor, it was not clear how to decline the installation of Wajam. The Wajam consent screen appeared with greyed-out text (see fig. 5). A box was pre-checked and the user could click “Back”, “Next” or “Cancel”. However, there was no description beside the pre-checked box or an explanation as to how one could proceed with the installation of the primary software without installing Wajam:

Fig 5: Wajam consent seen on installing “Dumpper” free software using Install Monster.

Fig 5: Wajam consent seen on installing “Dumpper” free software using Install Monster.Text version

Screen capture of a Wajam consent screen with consent text which are both coloured grey.

The consent text reads as follows:

“Get recommendations from friends on all websites you like to use. Wajam gives you personal results from Facebook and Twitter on websites like Google, TripAdvisor, Amazon and more. Facebook and Twitter user data is used by Wajam to give you personal results based on what you search. Wajam may use an add-on, local proxy, dll, cookies, pixels and/or other means to collect your IP address, URLs of the pages you visit and other information including the content of encrypted web pages to give you personal search results and show you advertising. Wajam may protect itself from other software that tries to interfere with it. You may opt out of third party advertising and remove Wajam at any time. Learn more. To request removal or disabling of this computer program, please contact us at this electronic address.”

There is a pre-checked box with no text beside it.

The text continues on the next line, and reads as follows:

“By clicking “Next”, I agree to Terms of Service and Privacy Policy and consent to install and enable Wajam for all browsers. Please contact us for more information”

The words “Learn more”, “electronic address”, “Terms of Service”, “Privacy Policy”, and “contact us” are hyperlinked.

Multiple offer process

- In a multiple offer process, an individual consents to install both the primary software they selected and all the potentially unsolicited programs within the bundle offered by the distributor, by means of a single consent screen:

Primary software Single consent screen Social2Search Express/Customized installation Software C Software D… - The respondent explained that it experimented with a multiple offer process to distribute the Social2Search software between August and November 2016. The respondent stated that it did this to remain competitive in countries which accept this as a common and acceptable form of user consent to install software. It stated that it had advised distributors to be consistent with what well-known brand software had implemented.

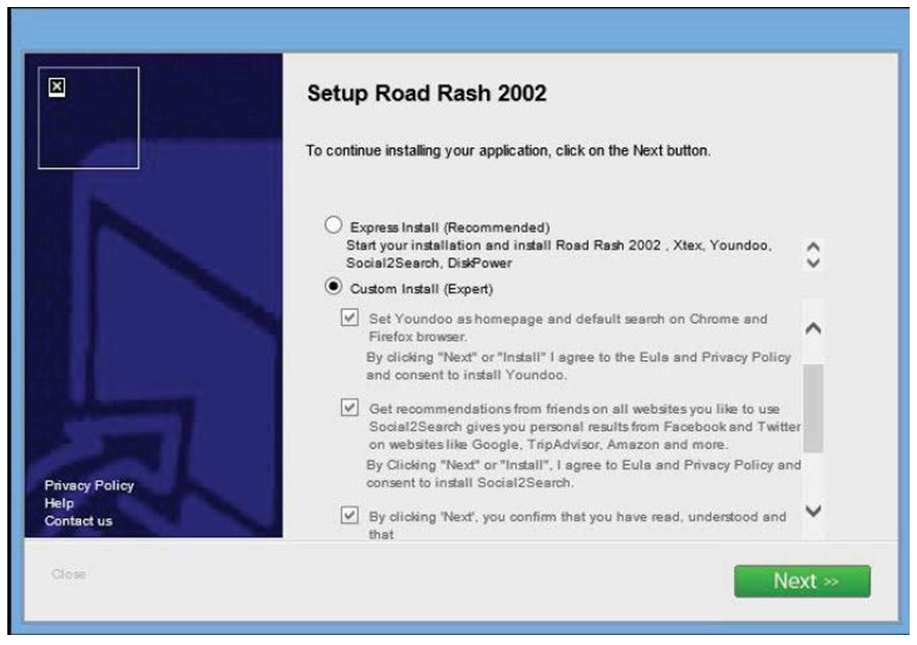

- The respondent provided us with examples of multiple offer consent screens. We also saw others during our testing. The multiple offer consent screen in fig.6, highlights some of the concerns we found:

Fig. 6: Social2Search and other software offered during an installation of “Setup Road Rash 2002“ free software offered.

Fig. 6: Social2Search and other software offered during an installation of “Setup Road Rash 2002“ free software offered.Text version

Screen capture of an consent page for a program called « Setup Road Rash 2002 » and four additional bundled software programs.

The consent page offers an individual two choices:

The first choice is for an individual to “express install” the Setup Road Rash 2002 and the four other bundled software programs, which include the Social2Search software. This is marked as a “recommended” choice.

The second choice is for an individual to “custom install” the Setup Road Rash 2002 program and then select one or more of the four additional bundled programs they want by checking a box for each program. This is marked as an “expert” choice.

Individuals are then asked to click on a “Next” box which will install the selected programs.

- The pre-checked box is the “Express Install (Recommended)” option, which automatically installs the primary software and all bundled software;

- The “Close” button text is greyed-out and in a very small font compared to the “Next” button. It could be easily missed or dismissed as a non-active option;

- The links to access relevant privacy policies or other material describing the four additional unsolicited software programs, including Social2Search, appeared not to be clickable;

- To opt out of installing Social2Search, an individual needs to select custom install option labeled "Expert", which could dissuade individuals from selecting this option. Once the option is chosen, check boxes appear for each piece of software. The boxes are pre-checked in a similar manner to an express install option and the text is greyed-out as if changes are not possible, and;

- Only two of the four additional software programs are fully shown on the screen. An individual would need to move the scroll bar to find more information on the last two programs. If the "Next" button is used in error, all four additional software programs are immediately installed.

Third-party distributors

Quality assurance

- To evaluate and monitor third party distributors, the respondent established a Quality Assurance ("QA") team. At the time of our site visit, the QA team was comprised of a supervisor and an analyst. The respondent stated that its QA team communicated compliance obligations to distributors and required distributors to obtain prior approval of their proposed consent processes to ensure they are compliant with its Distribution Agreement. Finally, the QA team monitored distributors' ongoing activities and provided intelligence to senior management highlighting instances of distributor non-compliance.

Pre-approval of consent process

- Potential distributors were provided with a Wajam or Social2Search Partner Guide ("Partner Guides"). Partner Guides provided distributors with technical and compliance information as to how they should integrate offers for Wajam or Social2Search software into larger software bundles and provided examples of acceptable consent practices.

- The respondent stated that each distributor had to provide a working demonstration of how the respondent's software will be promoted online. This was tested and the results recorded in a "Bundle QA Report" (the "QA report"), an example of which was provided to our Office. The QA report assessed whether the images, text, links and user interfaces in the consent process were clear, compliant and functioned as expected. If any criteria were deemed a "fail", the distributor had to make modifications until the installation process is approved.

Distribution Agreements

- As noted above, each distributor signed a Distribution Agreement. Within each agreement, a distributor was required to comply with the respondent's Distribution Guidelines and applicable law. The Guidelines required that the distributor follow installation protocols, consistent with those contained in its Partner Guides and certain sections of TRUSTe's Trusted Download Program requirements.

- The Guidelines prohibited certain methods of distribution, including, in part: (i) silent installations (i.e., without notification or consent from a user); (ii) collecting personally identifiable information through the use of a keystroke logging function; (iii) inducing the user to provide personal information by intentionally misrepresenting the identity of the person seeking the information; (iv) misrepresenting the nature or purpose of the download; (v) removing, disabling or rendering inoperative a security, anti-spyware or anti-virus technology installed on the computer, and; (vi) offering the software to individuals using incentivized installations.

- The Guidelines set out limits that distributors had to adhere to when distributing Wajam or Social2Search with other software, e.g., Wajam or Social2Search was not to be bundled with software categorized as adware, spyware, person-to-person file sharing, or Torrent software, or contain or promote a list of prohibited subjects, products or services.

Monitoring distributors' activities

- The respondent stated that the QA team monitored how the respondent's software was distributed to users. However, the respondent claimed that distributors did not always disclose the names of the websites or download portals they used or the names of the primary software with which they bundled Wajam or Social2Search. According to the respondent, this made the task of policing the bundles “daunting” and a process of “trial and error”. In effect, the respondent had to try and find a bundle that contained its software and this could take “hours and/or days”.

- To assist in narrowing down the QA team's search efforts, the respondent collected a user's browsing history for a period of 4 hours prior to installation, up to a maximum of the last 20 URLs.Footnote 11 The QA team then retraced the web pages visited by the user to try and identify bundles containing Wajam or Social2Search and assess the installation process experienced by the user. However, because of differences in how distributors offered software bundles, the respondent was required to test the collected URLs again and again using different geographic locations and times in order to be able to eventually find bundles containing its software.

- Once it found a bundle containing the software, the QA team screen-captured its monitoring and assessment of distributor installation of its software. Where evidence of non-compliant installation was found, the respondent stated that it was escalated to senior management for follow-up with the distributor. This screen-capture content was included with warning communications sent to distributors requesting corrective action. The respondent provided several examples of this follow-up with distributors to our Office.

- The respondent stated that its QA team also conducted trend analyses of installations, clicks and uninstallations to detect potential compliance problems with distributors. The respondent explained that a monthly trend analysis report highlighting these problems was sent to senior management and provided an example of a recent report.

Evidence of non-compliance issues and follow-up by the respondent

- Despite the above measures, we noted evidence of significant compliance problems with distributors. We reviewed 21 sets of e-mail correspondence sent by the respondent to 18 distributors between November 2014 and February 2016. These e-mails cited problems concerning the failure of distributors to comply with the terms of the respondent's Distribution Guidelines. Examples included: (i) the unauthorized silent installation of the software; (ii) the software being offered without an active "decline" option; (iii) a "decline" link being offered instead of a "decline" button and the button not being of equal size and prominence as the "accept" button; (iv) the offer screen used missing key text, and; (v) the software being offered as part of an express installation of several software programs, i.e., included in a multiple offer process without the respondent's knowledge or agreement. As noted above, our own testing revealed similar problems with distributors with respect to the consent screens being used.

- The respondent stated that when it detected non-compliance it would immediately contact the distributor responsible. In certain communications we reviewed, the respondent told the distributor to pause the offer until it was corrected. In other instances, the respondent sought to withhold, or reduce, installation payments from non-compliant distributors. It also claimed to have ceased doing business with four distributors. However, it was not always clear from the records examined what corrective action was taken by the distributors, or whether corrective action was verified by the respondent, to ensure the issues were fully addressed.

- Further, notwithstanding the respondent's claim to have terminated business relations with four distributors, there was written evidence of only one agreement being terminated. This was in December 2016, long after we had notified the respondent of the commencement of our investigation. There was also no indication that the respondent, once it discovered that its software had been installed in contravention of its policies, attempted to contact those individuals affected or to cease collecting personal information from them.

User complaints - lack of consent to install

- The Wajam and Social2Search websites recognized that some individuals may have inadvertently installed the software. In particular, a FAQ on the websites acknowledged that “…we have received some complaints when users were unaware of clicking the consent button … we apologize if you have unintentionally consented to downloading our social search technology.” The FAQ also explained that the software is sometimes bundled with other software but that “…Our product is not allowed to be installed unless you have given consent to do so. Social2Search is never secretly added or forced upon the user…In every case you have the opportunity to opt-out of the download.”Footnote 12

- We examined the contents of the respondent’s Wajam and Social2Search Community Manager's mailboxes for the period January 2015 to December 2016. The mailboxes contained thousands of communications (referred to by the respondent as "interactions"). The respondent explained that while this appeared to be a high number, the interactions represented a tiny fraction of Wajam and Social2Search users.

- On closer analysis, many of the communications appeared to be unsolicited communications, e.g., marketing promotions from third parties. Nevertheless, we found hundreds of instances where users claimed they had not consented to the installation of the software:

“hi, today I started to notice your ads all over my browser. i never installed this to begin with and there's no sign of this in programs or my browser extensions. iv [sic] even tried the downloadable installer and still can't get rid of it. Why is this happening?”Footnote 13

“Somehow your invasive ad machine has installed itself on my school computer. I have tried to uninstall, but of course, to no avail. Just as I am sure you intended. How dare you invade someone's computer with your ridiculous ad machine. I am unable to even enjoy browsing anymore because of the crap your site puts on my screen.”Footnote 14

- In response to the above, the respondent stated that it often received complaints about software wholly unrelated to Wajam and Social2Search, since its software and contact information was readily available to users and never hidden, unlike the contact information of some other software providers which it did not name.

- While the FAQ suggested users may have inadvertently given their consent to install the software, we saw that during the same time period, the respondent was raising several concerns with distributors about non-compliant consent processes, including instances of alleged silent installations of its software (i.e., that is installations that occur without users having been presented with a consent screen).Footnote 15 Also, as noted above, our own testing revealed problems with the consent screens used by certain distributors.

The information provided to individuals about the software

- As noted above (see paragraph 26), we found that information on the websites incorrectly stated that the software could link to users' social media accounts such as Google+ and Facebook, when in fact, apart from Twitter, this had not been the case for some time. Despite this, the respondent continued to heavily promote and market the ability to link the software to these social media sites during the course of our investigation, long after the links had ceased to function for all except Twitter accounts.

- The respondent’s standard consent screen contained a link to its Privacy Policy which described how the respondent collected, used and disclosed personal information. We noted a number of discrepancies in the information provided in the Policy.

- The Privacy Policy described the information which the respondent collected for each user. Of significant concern, the Privacy Policy described some of this information as “Non-Personal Information” despite the fact that it was linked to an individual user, including: (i) a user’s Internet service provider; (ii) IP address; (iii) the type and ID of the computer or device; (iv) the operating system and its version; (v) the date and time of installation; (vi) the default browser; (vii) a list of all add-ons installed on a user’s browser; and (viii) all applications that are installed on the computer or device. The respondent subsequently stated that it did not in fact collect item (i) above, despite this being stated within the Privacy Policy.

- We also noted that the respondent would assign each user a unique identifier. The respondent stated that the identifier was an MD5 encrypted hashFootnote 16 created automatically by the software on the user's computer and based on the user's mac address and hard-drive serial number. This was used to identify and track each user for analytical purposes yet this was neither disclosed nor explained in the Privacy Policy.

- The Privacy Policy did not fully describe all of the personal information that the respondent collected, or the purposes for which the information was used. In particular, we noted that the respondent collected and used a user's geolocation (country or region) at installation and during later user browsing sessions, as well as limited user browsing history prior to installation.Footnote 17 The respondent explained that geolocation affected the ads displayed to users and that prior browsing history was used to track compliance by distributors and for other quality assurance purposes.

- The respondent's Privacy Policy also contained inaccuracies and was not up to date. In particular, it stated users are required to provide their social media log-in credentials for certain features of the software to work. However, the respondent clarified that, until its integration with Facebook and Twitter ceased in 2014 and 2017 respectively, its software used Facebook and Twitter APIsFootnote 18 to allow users to log on to their respective user accounts and enable it to collect the social media content. The respondent added that it did not collect social media content by any other means, nor did it collect, use or retain users' log-in credentials. The respondent acknowledged that this aspect of its Privacy Policy was outdated and no longer accurate, and needed to be revised.

- With respect to the display of ads, the Privacy Policy explained how users could opt-out of receiving advertising, but did not explain that the respondent's servers continued to collect certain browsing information and search query data from users that had opted out. The software's integration with supported websites, and serving of ads to such websites could be partially controlled through the respective Wajam and Social2Search settings pages. The default settings, which were numerous, were pre-checked or “switched on”. The respondent claimed that the settings allowed users to use the full functionality of the software from installation and was appropriate as the software did not use sensitive keywords to serve ads (see fig. 7). Unchecking the boxes disabled ads but did not stop the collection of a user's browsing history and search queries on the unselected websites.

Fig. 7: Social2Search settings and opt-out page.

Fig. 7: Social2Search settings and opt-out page.Text version

Screen capture showing user settings and opt-outs for Social2Search, including a section for Frequently Asked Questions, Ads Settings, Shopping Settings, Language preference and “Search Engine Options”. All settings boxes are pre-checked by the company.

If users wish to opt-out of any settings on the page they must “un-check” the relevant boxes.

There are 91 featured websites and check-boxes which appear in the section entitled “Search Engine Options”.

- Finally, we examined a TRUSTe "Trusted Download Program ("TDP") Findings Report" of the Wajam software dated August 18, 2016. In the TDP report, recommendations were made to the respondent to provide additional information to users, including inserting additional text in its EULA and Privacy Policy regarding how the software functions. The respondent claimed that the changes requested by TRUSTe were not made to the documents, as it was awaiting the outcome of the OPC's investigation.

- The respondent stated that it had voluntarily started to update its privacy material and build a privacy program, but had then decided to terminate its TRUSTe certification agreement and to sell its assets to IMTL. As a result, the work had ceased.

Withdrawal of consent - uninstalling the software

User complaints – difficulties in uninstalling the software

- Our research identified multiple users’ online comments about the difficulty of uninstalling the software:

“…After messaging them regularly they finally are addressing the issue. Previously their responses were more or less an apology mixed with promoting their product. Even though I told them repeatedly I already uninstalled, their only solution was how to uninstall, avoiding the fact that that despite that I have done so, it keeps installing. Maybe later that day, or 2 weeks later, but it keeps coming back.”Footnote 19

- We also found many complaints about the difficulty in uninstalling the software within the Wajam and Social2Search Community Manager's mailboxes:

"…I have followed all your steps on how to uninstall your program. All attempts have failed. Through my control panel to uninstall programs, I have attempted to uninstall your software and my computer indicates your software is uninstalled. However it is not removed from my programs list. Your software is still active on my computer, even after going to your website and following all directions on how to uninstall your software. I am requesting assistance on actually removing your annoying software from my computer."Footnote 20

"I have followed every single suggestion to remove your unwanted, un-ordered, unauthorized ads from my computer. I have tried to remove from every single source and still your unwanted ads are ruining my life! I am about to post a rip off report and google negative ads and yahoo negative ads and bing negative ads as well as any other place I can place negative ads about your unwanted, unwarranted, unauthorized ads that are ruining my computer…"Footnote 21

- The respondent's Community Manager sent a standard response to all such complainants which included a short description of the software and a link to the respondent's Privacy Policy. Each response contained a link to the respondent's uninstaller program with instructions on how to uninstall the software. If the uninstallation did not work and complainants came back to the Community Manager, they were either sent instructions for a secondary uninstallation method involving an executable file or they were advised to temporarily disable their anti-virus software, if it appeared the software’s uninstaller was being blocked, so as to allow the uninstaller to work.In our examination, these additional uninstallation methods worked.

Uninstalling the software – methods and results

- The respondent claimed that its software could be deleted quickly and easily from a user's device. Instructions on how to remove the software was available on the Wajam and Social2Search websites, including video instructions to walk users through the uninstallation process on Wajam (see fig. 8 below):

Fig. 8: How to remove/uninstall at Wajam.

Fig. 8: How to remove/uninstall at Wajam.Text version

Screen capture entitled “How to remove/uninstall”, with step by step instructions for the user on how to remove or uninstall Wajam using three different methods: ‘Wajam Uninstaller, Windows Control Panel, and Chrome Extension.

There is also a note on cookies at the bottom of the page.

There is a video on the right hand side of the screen, with an image below related to the uninstallation instructions for the Wajam Chrome extension.

- We tested two uninstall methods: (i) the “Add/Remove” function using the built-in uninstaller program included in the software, and; (ii) the stand-alone uninstaller program downloaded from the website. In each case, our user accounts were taken through an uninstallation process which removed the software.

- However, after the uninstallation process was complete, we observed that sections of the software code could remain on a user's computer within their browser's data cache.Footnote 22 Web pages that were previously cached by a browser could, in turn, trigger a user’s browser to continue to contact the respondent’s servers, and lead to the new collection of personal information and the ongoing display of ads by the respondent. The respondent claimed that this activation of the software was inadvertent and limited in nature. It would only occur until the cached web page content involved was reloaded and updated on the web page's hosting server.

- The respondent further explained that it took steps to prevent such reactivation of its software both through its distribution agreements which specifically precluded distributors from enabling such activityFootnote 23, and through its “How to uninstall” page which directed users to clear their browser cache to ensure that no remaining information from the software was present on their computer.

- While we noted that the warning text inserted by the respondent directed users to clear their browser caches, the text was linked to one uninstallation option only, rather than included as a general statement applicable to all uninstallation processes, like the text on cookie removal. We also noted the respondent did not provide instructions on how to perform the clear data cache function.Footnote 24

- The respondent's unique user identifiers were also retained on users' computers after uninstallation appeared to be complete. The respondent claimed that the identifiers should have been removed from users' own computers or devices during the uninstall process and that the failure to remove the identifiers was either a result of a software bug, or the result of an incomplete uninstall.

Uninstalling the software – unsolicited ads and fake offers

- During our testing, we found that our user accounts were presented, in approximately 10% of uninstallations, with unsolicited ads, potentially unwanted programs, or directed to fake software. The ads and programs were served through a third-party ad network which was called-up to issue the material by the respondent's source code. This could enable third-parties to potentially collect user personal information through malicious means and without consent, should the user interact with the ads or programs. This activity was triggered by user visits to the post-uninstallation web page (see fig. 9), which in turn automatically generated pop-up windows promoting the unwanted content.

Fig. 9: Post-uninstallation web page at Social2Search.

Fig. 9: Post-uninstallation web page at Social2Search.Text version

Screen capture of the Social2Search post-uninstallation web page showing the text « You’ve successfully uninstalled Social2Seach from your browser. We’re sorry to see you go.”

There is an empty text-box with the following text to its left: “If you have any suggestions on how we could improve Social2Search we would love to hear your thoughts”. There is a grey button below the empty textbox that reads “Send Feedback”.

- Offers served by the ad network included, but were not limited to, anti-virus software claiming our test computers were infected and fake Adobe flash software that was not associated with Adobe.

- We brought these incidents to the attention of the respondent's senior management and technical staff who indicated that they had never seen this activity before. During the site visit, we conducted a test to demonstrate our experience on the website uninstallation page. An ad appeared which was confirmed as coming from the ad network called-up by the respondent's own source code. The respondent stated it had no agreement with the ad network supplying the ads and agreed to immediately disable the code, so that no further calls for ads would be made after the uninstallation process.

Section 3 – Retention of personal information:

- The respondent's Privacy Policy stated, in part:

"User Rights

PLEASE NOTE THAT UNLESS YOU INSTRUCT US OTHERWISE WE RETAIN THE INFORMATION WE COLLECT FOR AS LONG AS NEEDED TO PROVIDE THE SERVICES AND TO COMPLY WITH OUR LEGAL OBLIGATIONS, RESOLVE DISPUTES AND ENFORCE OUR AGREEMENTS."Footnote 25

- The majority of the information collected by the respondent was transmitted to its servers in the form of “events”. For each “event”, the information captured by the respondent included: (i) the unique user identifier assigned by the respondent; (ii) the website visited; (iii) the search or shopping query initiated by the user (keywords or query entered); (iv) the number of ads successfully delivered to the user, and; (v) the identifier of the ad that was clicked.

- At the time of our site visit, the primary database contained all events submitted to the respondent's servers since the launch of Wajam in October 2011 and Social2Search in May 2016. The information stored in this database was being kept in a raw, unparsed format and contained personal information which could be attributed to individual users, including sensitive search keywords. The respondent indicated that the database contained approximately 400 terabytesFootnote 26 of information, which is a massive amount equivalent to the storage capacity of approximately 8,000, 50 gigabyte dual–layer Blu-Ray discs.

- The raw user information in the primary database was not subject to any written rules, procedures or schedules governing its retention and destruction, whether automatic or manual. The content, including unique user identifiers, was retained even when a user uninstalled the software. The respondent indicated that the information in this database was not used directly. The respondent claimed that it retained user identifiers to prevent fraud, specifically the payment of extra installation fees to distributors where multiple installations and uninstallations took place in quick succession.

- The search queries performed by users were parsed and copied from the primary database into three other databases: (i) the business intelligence database; (ii) the business database, and; (iii) the non-persistent memory database.

- The respondent explained that information copied to and residing in the business intelligence database was in aggregate and depersonalized form, i.e., it was not linked to any specific users. Rather, it was used to analyze trends, generate reports and compile metrics. Our examination of this database during the site visit found that the content was consistent with the respondent's claim. The respondent added that the retention of this data was subject to disposition rules and was kept for a few hours up to 90 days.

- The information residing in the business database was again depersonalized. The behavior of the Wajam or Social2Search software on users' machines depended on this database, as the respondent's servers utilized the information found here to retrieve ads, deliver “social media enabled search results” to the user or collect event data transmitted by the software. The retention of this information was subject to disposition rules and was kept for 1 month up to 18 months.

- Finally, keywords or search queries stored in the non-persistent memory database remain linked to particular users. They supported the re-targeting of ads where a user performed a search that did not immediately generate an ad. Re-targeted ads rely on historical keywords retained here. This database was automatically flushed when the server hosting it was switched-off or restarted. While this data was therefore not retained indefinitely owing to this restart function, it was also not subject to any fixed destruction schedule.

- The respondent later informed our Office that it would not be transferring any personal information of Canadian users to IMTL. The transfer of information of non-Canadian users would be limited to MD5 encrypted hash values, user installation dates and aggregated (i.e. non-identifiable) analytical information contained within its business intelligence database.Footnote 27

- The respondent advised that all user information contained within its hard drives would be held by a third party data management corporation for the duration of the investigation and then securely destroyed.

Section 4 – Safeguards:

Use of encryption

- The respondent's May 2016 Privacy Policy stated:

"How do we safeguard your personal information?

Wajam makes best efforts to use security methods and encryption when handling sensitive data (i.e., handle the user data securely, including transmitting it via modern cryptography)…"

- Contrary to the above assurances, our testing found that the respondent did not encrypt user information collected and transmitted to the company's servers following initial installation of its software. Rather, the respondent immediately began collecting information from a user (as described in paragraph 89) and transmitting it to its servers through regular unencrypted (HTTP) channels.

- Our initial testing also found that the respondent did not encrypt user keywords for search engine and shopping website queries. Subsequently, the respondent’s practice changed so that user keyword searches were collected and transmitted to the respondent in both encrypted and unencrypted form, depending upon the security profile of the source website from which a user conducted a search or query.

- In one test, we conducted a search query through a well-known search engine. The query was encrypted by the search engine and was duly transferred in encrypted form (HTTPS) to the respondent's servers. In a second test, we conducted a similar search query through an e-commerce website. The query was unencrypted by the e-commerce website and transmitted in unencrypted form to the respondent's servers.

- We followed up with the respondent to understand its policy on encryption. In particular, its claim that it did not collect sensitive information from users and yet it collected all user keyword searches (which could clearly include sensitive search terms).

- The respondent confirmed that information “at rest” in its primary database was not encrypted, even though it contained all user information in “raw” format. The information was attributable to specific users and included potentially sensitive search keywords.

- The respondent clarified that while user information in its non-persistent memory database comprised keyword searches linked to specific users, they were vetted to exclude sensitive categories and keywords consistent with the filters used by its ad providers. The information while personal was used for quality assurance purposes and the re-targeting of ads and the information was regularly purged.

- While keywords in the respondent's business intelligence and business databases could include sensitive keywords, they were depersonalized and not associated to any users. They were also subject to deletion after set periods of time.

- The respondent added that it had implemented additional physical, technical and administrative safeguards that it believed were appropriate to protect the information in its custody. These were reviewed during the site visit by OPC technical staff and included access controls and logs, limited access to servers and other confidential measures.

Findings

Section 1 - Accountability

- Principle 4.1.4 of Schedule 1 of the Act states that organizations shall implement policies and practices to give effect to the principles, including: (a) implementing procedures to protect personal information; (b) establish procedures to receive and respond to complaints and inquiries; (c) training staff and communicating to staff information about the organization's policies and practices; and (d) developing information to explain the organization's policies and procedures.

- Despite claims made by the respondent to our Office under sworn affidavits, claims made to TRUSTe in a questionnaire in October 2015Footnote 28, and additional claims made to us verbally during a site visit, the respondent was unable to produce evidence that it had appropriate written policies and procedures to give effect to the privacy principles under the Act. In fact, there was an apparent absence of written processes, procedures or templates to support compliance with the privacy principles. This includes the protection of users' personal information and the retention and destruction of personal information.

- Taking into account the above, we are of the view that the respondent contravened principle 4.1.4 (a) of Schedule 1 of the Act.

- We also note that the respondent was unable to produce supporting evidence that it had issued any privacy-related communications, or provided any relevant privacy training to its employees regarding its privacy policies or procedures, in contravention of principle 4.1.4 (c) of Schedule 1 of the Act.

- Overall, it was clear that the respondent had no demonstrable privacy management framework in place, notwithstanding the volume of sensitive personal information, including certain browsing information and search queries, that it was collecting to support its business model. We note that our office issued guidance in 2012 on the importance of having such a framework and implementing accountability procedures and controls.Footnote 29

Section 2 - Consent

- Principle 4.2 of Schedule 1 of the Act states that the purposes for which personal information is collected shall be identified by the organization at or before the time the information is collected.

- Principle 4.3 of Schedule 1 of the Act states that the knowledge and consent of the individual are required for the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information, except where inappropriate.

- Principle 4.3.2 of Schedule 1 of the Act requires "knowledge and consent". Organizations shall make a reasonable effort to ensure that an individual is advised of the purposes for which the information will be used. To make the consent meaningful, the purpose must be stated in such a manner that the individual can reasonably understand how the information will be used or disclosed.

- Section 6.1 of the Act provides that the consent of an individual is only valid if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting.

- Principle 4.3.5 of Schedule 1 of the Act states, in part, that in obtaining consent, the reasonable expectations of the individual are also relevant and that consent should not be obtained through deception.

- We also note that Canada’s Anti-spam Legislation (CASL) amended PIPEDA to severely restrict the circumstances in which an organization can collect and use personal information without consent via software that has been installed on an individual’s computer.Footnote 30 Although this provision is not directly at play in this investigation because the respondent does not rely on an exception to consent, CASL, and the amendments to PIPEDA made by CASL, highlight the importance of software developers obtaining meaningful express consent for the installation of their software that results in the collection and use of personal information.

- Individuals selecting free software programs need to take appropriate care in reading and availing themselves of information about the software and any bundled software that comes with it, before giving their express consent to install. Software developers and distributors also have a responsibility to be open and transparent with individuals about how their programs work and individuals' options during the installation and consent process.

- This is especially so where the software is unsolicited and comes bundled with offers to install other unrelated software. In such instances, individuals are often not aware what software programs will be presented to them for download until they begin the installation process. A clear and transparent process was crucial in this case given that installation of the software could result in the collection and use of a large amount of personal information (a massive amount when aggregated over time), including online search queries, even if an individual took no further steps to log-in and create an account and did not use the software’s social search functionality.

- During our investigation and testing we identified multiple concerns with how the respondent was meeting its obligations to obtain consent under the Act. Our concerns were not inconsistent with the online comments and consumer complaints that we reviewed. These concerns fell under four broad headings: (i) problems with third-party distributors, (iii) problems with multiple-offer screens, (iii) problems with the information provided to individuals about the software, and (iv) problems with uninstalling the software.

Third-party distributors

- While the respondent appears to have attempted to vet and monitor the activities of the many distributors who distributed its software, there were clearly problems with this method of distribution.

- The respondent used a third-party distribution model which financially incentivized distributors to push as many installations as possible. As the respondent itself acknowledged, it was difficult and time consuming to actually monitor whether distributors were in fact complying with its Distribution Guidelines, which created a significant risk that non-compliance would go undetected.

- In the 15 month period that we examined, the respondent's QA team identified problems with 18 separate distributors using installation processes that did not comply with its Distribution Agreement and Guidelines. Examples included silent installation of its software, incomplete consent text and non-working consent options. Our own testing also identified several concerns with the installation processes adopted by distributors to distribute the respondent's software, including: (i) the distribution of out of date versions of the software (along with out of date versions of the Privacy Policy); (ii) the greying out of decline or close buttons, which could be perceived as non-functional, and; (iii) the use of confusing options that could potentially mislead users to install the software such as error messages or pre-checked boxes.

- The above, coupled with the respondent's findings through its own testing and complaints from users, highlights that the respondent was aware for some time that the practices of several distributors were leading to the installation of its software and the collection and use of personal information, without meaningful consent.

- There was evidence that the respondent communicated the consent problems it observed to distributors and requested prompt action to resolve the issues. However, this was at best an ex post measure and does not appear to have significantly addressed the problem of non-compliance. Furthermore, based on the records presented to us during the investigation, the extent of the respondent's follow-up with certain distributors was inconsistent and disappointing. In certain instances, the respondent checked with distributors to ensure that corrective action was taken. In other instances, evidence of communications between the respondent and distributors appeared incomplete and inconclusive.