Investigation into the personal information handling practices of “Compu-Finder” (3510395 Canada Inc.)

PIPEDA Report of Findings #2016-003

April 21, 2016

Report of Findings

Complaint under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA” or the “Act”)

Introduction

- On November 28, 2014, our Office initiated a complaint against 3510395 Canada Inc. ("Compu-Finder") under subsection 11(2) of the Act.

- We opened the complaint having reasonable grounds to believe that Compu-Finder was collecting and using e-mail addresses of individuals to send e-mails promoting its business activities, without the consent of the individuals concerned.

- Compu-Finder was notified of the complaint by our Office on February 2, 2015.

- In conducting our investigation, our Office:

- Examined Compu-Finder's various websites;

- Reviewed online media and other public content about the organization;

- Examined submissions and reports sent to the CRTC's Spam Reporting Centre (the "SRC")Footnote 1 about the organization (and associated Internet domains);

- Interviewed 8 of the individuals who made these submissions and reports, and;

- Analyzed representations and documents received from Compu-Finder between March 18 and October 19, 2015.

- On March 5, 2015, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission ("CRTC") issued a Notice of Violation to Compu-Finder pursuant to Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation ("CASL").Footnote 2 Compu-Finder subsequently requested that the CRTC review the Notice of Violation. The CRTC's proceedings with respect to this matter were ongoing as of the date of this report of findings (the "report").

- During the course of our investigation, the CRTC shared information with our Office that was provided to it by Compu-Finder through the CRTC's proceedings. The information was shared under paragraph 58(1)(a) of CASL and the information sharing Memorandum of Understanding agreed between the OPC and CRTC.Footnote 3

- During the course of our investigation, we identified significant concerns about the integrity and comprehensiveness of the information in Compu-Finder's representations.

- Information provided by Compu-Finder appeared to be incomplete in certain instances. Further, certain statements made in representations were found to conflict with statements and documents made in other representations and when asked to provide records to us in support of statements it had made, Compu-Finder was not always able to do so. This is despite the fact that content sent to our Office on March 18 and 25, 2015 was supported by a sworn affidavit from the president of the organization, attesting that the information provided was accurate and complete.

- The results of our investigation led us to conclude that Compu-Finder was not aware of, or did not respect, its privacy obligations under the Act. We identified that in many instances Compu-Finder lacked appropriate consent for the collection and use of e-mail addresses for the purposes of sending out e-mails promoting its training courses. We also discovered an absence of a basic privacy accountability framework and a notable lack of openness regarding its privacy policies and practices.

- Therefore, on August 8, 2015, we issued a preliminary report of investigation (the "preliminary report") which contained nine recommendations to bring Compu-Finder back into compliance with the Act.Footnote 4

- We also recommended that Compu-Finder commission an independent third-party audit of its privacy programs following implementation of its compliance measures, and provide us with a copy of the auditor's report and the organization's response to any audit recommendations.

- In reply, Compu-Finder explained that its earlier submissions to our Office were not intended to mislead. While imprecise in certain aspects, they were provided by the organization in good faith and on a best efforts basis, without the assistance of external legal counsel.

- Compu-Finder added that it had made a concerted effort to prepare for the introduction of CASL on July 1, 2014. It believed that its business-to-business marketing model and activities were consistent with the implied consent provision in CASLFootnote 5 and business-to-business exemption available under the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations made pursuant to CASL.Footnote 6 Compu-Finder referred to "substantive representations" it had made to the CRTC in May 2015, as supporting evidence for its position.

- In addition, Compu-Finder argued that it had obtained implied consent under the Act and that, in any event, the e-mail addresses it had collected from websites and other sources were "publicly available" and therefore consent was not required.

- Compu-Finder asserted that the introduction of the new definition of "business contact information" and section 4.01, carving-out such information from the application of the Act, following the introduction of the Digital Privacy Act, also would support its position.Footnote 7 It claimed that section 4.01 accurately described its primary use of personal information when sending electronic communications to its target audience, i.e. an entirely business-to-business context. It believed that section 4.01 also reinforced the legitimate nature of its approach to the use of non-sensitive business contact information for the purpose of sending commercial e-mails.

- Compu-Finder acknowledged that it had used address harvesting software to collect approximately 170,000 e-mail addresses from websites between November 2012 and February 2014. As such, it argued that our Office was seeking to retroactively apply the "address harvesting" provisions of the ActFootnote 8 to its automated collection of e-mail addresses, which had taken place before these provisions were inserted into the Act on July 1, 2014. However, we note that Compu-Finder continued to use approximately 28,000 of these e-mail addresses to send commercial e-mails after July 1, 2014.

- Notwithstanding the above, Compu-Finder agreed to implement our recommendations on a "without admission" basis. Three of the recommendations were implemented before the issuance of this report. Compu-Finder agreed to implement the remaining recommendations within various timelines from the date of issuance of this report of findings.

- As a result of the above, we have determined that the complaint is well-founded and resolved in part and well-founded and conditionally resolved in part.

- Our Office has entered into a compliance agreement with Compu-Finder, aimed at ensuring its compliance with its privacy obligations, as allowed for under subsection 17.1(1) of the Act.Footnote 9

- This Report of Findings examines Compu-Finder's personal information management policies and practices, identifies the organization's contraventions of the Act, sets out the recommendations made by our Office in the preliminary report and summarizes Compu-Finder's response to the results of our investigation.

Summary of Investigation

Compu-Finder

- Compu-Finder is a federally incorporated company with an office located in the town of Morin-Heights in the province of Quebec.Footnote 10 It is also a registered company in Quebec.Footnote 11

- The organization operates under various names, including "Académie Compu-Finder", "Compu-Finder Inc." and "ACF Management". For the purposes of this report, we refer to the organization as Compu-Finder throughout.

- Compu-Finder promotes itself as an organization providing face-to-face, professional training courses in Montréal and the city of Québec:

[Translation]

Compu-Finder's training courses are predominantly promoted and delivered in French.

Welcome to the Académie

A pioneer and leader in professional training for over 15 years, ACF Management is for managers and executives who want to equip their companies with 21st century management tools.Footnote 12 - When we commenced our investigation, Compu-Finder owned and operated four websites: compufc.com, acfmanagement.com, prosperer.ca and academiedegestion.com. Compu-Finder later relinquished its control of the first two websites and restricted its online activities to the latter two websites (the "prosperer website" and "academie website" respectively).

The e-mails sent by Compu-Finder

- Compu-Finder sends e-mails promoting its professional training courses primarily to employees of organizations operating in the private, public and not-for-profit sectors. During the investigation, it claimed that these e-mails were only sent to such employees and other individuals located in the province of Quebec and the National Capital Region in Eastern Ontario.

- We examined the online submission forms ("submissions") sent by individuals to the SRC through Industry Canada's anti-spam website, along with numerous examples of e-mails forwarded by individuals to the SRC via the dedicated e-mail address spam@fightspam.gc.ca ("reports").

- Our examination revealed that over a period spanning July 1, 2014 to April 9, 2015, the SRC received 1,015 submissions and reports from individuals concerning e-mails sent by Compu-Finder. Compu-Finder ceased sending commercial e-mails on April 9, 2015, on a temporary basis, during the course of the CRTC's and OPC's proceedings.

- The submissions and reports revealed that the e-mails sent by Compu-Finder are usually addressed to individuals' business e-mail addresses, e.g., johndoe@companyxyz.ca. Approximately 5% to 6% are addressed to individuals' personal e-mail addresses, e.g., johndoe@gmail.com. While a similar percentage are sent to generic business e-mail addresses, e.g., info@companyxyz.ca.

- The example e-mails we examined were sent by unidentified titleholders rather than named individuals, e.g., “Team leader”, “Director General” and “Administrator”. Other e-mails appeared to be sent by generic senders using titles such as “New framework”, “Winning bids”, “Workload” and “Human resources” [These are translations of the titles used in the original emails].

- The example e-mails were sent to individuals and organizations from e-mail addresses with constantly changing domain names, e.g., "coursacf", "acfmanagement", formationacf", "objectifscommerciaux", "gestionnaireschan, "laformationsenligne" and "moncourtravailz" to name but a few.

- Compu-Finder provided our Office with a list of 293 Internet domain names currently registered to the organization through three different domain registration companies. We note that the use of generic senders and multiple Internet domains has the effect of obscuring the identity of the original sender and making the e-mails appear as if they come from different entities. Compu-Finder denied that this was its intent.

- Compu-Finder explained that the domains were used by its website, for the sending of e-mails, unsubscribe links and to accommodate the images linked to its advertising. It stated that it registered new domains when launching new services, courses and advertising and claimed that using separate domains assisted it in monitoring the success of each service and marketing campaign. Compu-Finder maintained that some of the domains listed could still be registered but no longer used. Compu-Finder added that it only renewed registrations as needed and let others expire.

- A sample of Compu-Finder e-mails forwarded to theSRC included invitations to training courses entitled:

- Calendrier de formation pour directeurs finance [Training schedule for finance directors]

- Comment construire un budget intelligent [How to create a smart budget]

- Comment exercer son autorité au travail [How to exercise authority at work]

- Devenir un excellent directeur [Becoming an excellent director]

- Devenir un “Super User” des réseaux sociaux [Becoming a social networking “Super User”]

- Nouvelles habilités pour adjointe de direction [New skills for executive assistants]

- Préparez des soumissions gagnantes [Preparing winning bids]

- Despite the e-mails being sent to individuals from different domain names and senders, the e-mails had a common appearance and content (format, font, spacing, use of colour and text). All of the e-mails listed the same Compu-Finder business contact address and many also included the Compu-Finder business telephone number. The e-mails also invariably referred to the same four hotel training venues in Montréal and Québec City. They also contained unsubscribe mechanisms and links directing recipients to the academie website.Footnote 13

- Contrary to Compu-Finder's representations to us, our examination of the submissions and reports made to the SRC also revealed that Compu-Finder's sending of marketing e-mails was not restricted to individuals and organizations located within the province of Quebec and the National Capital Region in Eastern Ontario. Although the majority of e-mails appear to have been sent to recipients in these regions, our review identified a proportion of e-mails sent to individuals located within other regions of Ontario and other provinces including British Columbia, Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador.

- This evidence appeared to be further supported by the extensive list of clients claimed by Compu-Finder on its academie website.Footnote 14 Our examination of the client list identified organizations located across Canada, in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and New Brunswick.

Compu-Finder's collection of e-mail addresses

The e-mail address lists

- Compu-Finder explained that its client base was entirely comprised of Canadian businesses (and their employees) and its marketing model was, therefore, business-to-business rather than business-to-consumer marketing. It added that it pre-dominantly targeted Québec-based businesses with payroll expenditures in excess of $1,000,000 as they are required under Québec provincial law to invest at least 1% of that amount in employee training.Footnote 15 Its e-mail address collection and subsequent marketing was, therefore, largely aimed at such businesses.

- In January 2014, its database contained approximately 475,000 e-mail addresses, which Compu-Finder asserted had been collected by various means.

- Compu-Finder stated that, in anticipation of the coming into force of CASL on July 1, 2014, it deleted a substantial number of the e-mail addresses from its database "removing primarily those addresses obtained from what it considered to be unreliable sources". Between January 2014 and July 2014, the number of e-mail records was reduced to approximately 100,000 addresses.

- Compu-Finder provided the CRTC with two spreadsheets containing lists of e-mail addresses held within its marketing database as of July 2, 2014 and August 25, 2014. The number of email addresses contained within each spreadsheet was approximately 100,000 and 107,000 respectively. It also provided information regarding the methods used to collect such addresses and the forms of consent obtained. The CRTC shared this information with our Office.

- Initially, we understood that the database lists provided by Compu-Finder to the CRTC were comprehensive. However, the e-mail addresses of many of the individuals making submissions and reports to the SRC about Compu-Finder's promotional e-mails between July and September 2014, were not listed in Compu-Finder's database. Yet these individuals were able to prove that they had received e-mails from Compu-Finder during that period by providing copies.Footnote 16 Some examples of individuals who received e-mails from Compu-Finder yet whose addresses were not in Compu-Finder's database are detailed further below.

- Compu-Finder uses three principal methods to collect the e-mail addresses in its database: (1) telemarketing (i.e. collecting e-mail addresses by calling organizations); (2) collecting e-mail addresses directly from individuals, and; (3) collecting e-mail addresses from websites and other sources. Compu-Finder claimed that it did not purchase e-mail lists from third parties. The following subsections of this report look at each of these collection methods in turn.

Collecting e-mail addresses by telemarketing

- Compu-Finder stated that it had conducted several targeted telemarketing campaigns to businesses between 2008 and 2011, and again between April 2014 and March 2015, to collect the e-mail addresses of their managers and employees. In doing so, Compu-Finder claimed that it informed individuals of the purposes of collecting their addresses, i.e., to send them information about the organizations' training courses.

- Compu-Finder stated that, in order to prepare for the coming into force of CASL, it created an internal telemarketing team in April 2014 to contact private, public and not-for-profit organizations to obtain e-mail addresses and promote their training courses. As of March 2015, the size of the team was seven employees.

- In anticipation of commencing its telemarketing operation, Compu-Finder entered into contracts with InfoCanada and the Centre de recherché industrielle du Québec [Quebec Industrial Research Centre] to extract business names, telephone numbers and the names of directors from those organizations' database holdings. The contract with InfoCanada allowed it to extract up to 148,000 contact coordinates within one year. It explained that it selected the companies by their volume of business.

- Compu-Finder stated that once launched, the proportion of calls made by its telemarketing team resulting in the collection of at least one e-mail address was 80%.

- We reviewed the e-mail lists that Compu-Finder stated were compiled exclusively by the new telemarketing team between April 2014, when the team was created, and August 2014, when the lists were provided to the CRTC. We counted approximately 38,000 e-mail addresses collected during this period. With Compu-Finder's cited conversion rate of 80%, the team of seven employees would, therefore, have had to make over 48,000 calls within 4 months.

- At our request, Compu-Finder provided a copy of the script used by their telemarketing team between April 2014 and March 2015:

[Translation]

Hello Sir or Madam, how are you?

My name is ___________________________ from ACF Management.

I have information to send to your director general. Could I have their e‑mail address please?

The name of the DG is…

Does Mr. or Ms. X have an assistant? What is their e‑mail address? Their name?

Thank you and have a good day! - The script did not explain that the purpose for requesting the e-mail addresses is to send individuals promotional e-mails about Compu-Finder's training courses.

- It is only when a person called seeks to ask questions about Compu-Finder and the nature of the information it intends to send, that any additional disclosure is offered:

[Translation]

Questions/answers

Who are you?

From which company? (details)

We are a management training company; we provide training across Quebec.

Information on what?

Information on management and administration methods. - The additional content does not explain that e-mail addresses will be collected and used to send marketing material promoting Compu-Finder's courses.

- It was clear from Compu-Finder's response that many of the e-mail addresses given in response to such calls are invariably collected from reception, administrative or support personnel within organizations, rather than collected directly from the actual individuals who use the e-mail addresses and who ultimately would receive Compu-Finder's promotional e-mails.

Collecting e-mail addresses directly from individuals

- Compu-Finder also provides various methods by which it can be contacted by individuals who may provide their e-mail addresses to Compu-Finder directly. Individuals can: (i) register and attend one of its training courses; (ii) become a member of its "Club Connoisseur"Footnote 17 program through the academie website; (iii) subscribe to its online newsletter through the prosperer website or the academie website; and (iv) submit an inquiry through either website's contact page. Each of these methods may result in the e-mail contact addresses being collected and used to send e-mails promoting Compu-Finder's training courses.

- Individuals visiting the prosperer website and academie website can also sign up to subscribe to Compu-Finder's newsletter by entering their e-mail address in a small box entitled "ABONNEZ-VOUS À NOTRE INFOLETTRE" [SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER].

- Finally, the websites have "contact" pages which enable individuals to submit general inquiries to Compu-Finder by providing their name, e-mail address, the subject of the inquiry and the message, before clicking the "envoyer" [send] button.

- The prosperer website and academie website do not contain general privacy policies which explain the organization's purposes for the collection of personal information, or how such information may be used for marketing purposes to individuals seeking to engage with the websites.

Collecting e-mail addresses from websites and other sources

- Compu-Finder claimed that it also built its database of e-mail addresses by searching lists of businesses on the Internet and manually collecting the most relevant e-mail addresses. Compu-Finder stated that it supplemented these e-mail addresses with others collected from business directories or lists on the Internet and websites of businesses likely to be interested in its courses. It added that it subscribed to the principal chambers of commerce to obtain potential contacts and had also approached certain trade associations.

- We asked Compu-Finder if it used computer programs to collect e-mail addresses contained within its database from the Internet. Compu-Finder asserted that it was not using such programs and had stopped collecting e-mail addresses from the Internet in 2014.

- Notwithstanding this assertion, we noted certain aspects of Compu-Finder's e-mail lists which pointed to the potential use of address harvesting software:

- We found extensive numbers of e-mail addresses of individuals working for the same employers (and using the same domains). It is unlikely that all of these e-mail addresses were collected manually, especially since in many cases they were not listed in a common location on the organizations' websites;

- The volume of e-mail addresses that Compu-Finder claimed that it collected manually from the Internet and other sources appeared unrealistic considering the limited resources available. The addresses included several thousand e-mail addresses which were not associated with employees of organizations, but rather began with generic prefixes such as "administration", "info" and "service", and;

- Certain e-mail addresses were linked to individuals and organizations that were overseas and others located in Canada which were geographically remote from Compu-Finder and its training venues. In one instance, we found an e-mail address within a database which appeared to be an address devoted to assisting students and faculty at a university report unwanted spam e-mails.

In short, we found it improbable that this volume, and these types, of addresses could have been included within the database if they were identified and copied manually. The presence of these e-mail addresses suggested that they were collected, at least in part, by using automated means. - Our conclusions were confirmed when Compu-Finder clarified that its earlier denial of the use of software to collect e-mail addresses from the Internet referred to its practice at the time, i.e., in March 2015. Compu-Finder expressed that its submissions to our Office regarding its collection of e-mail addresses were not intended to mislead, stating that while imprecise in certain aspects, they were provided by the organization in good faith and on a best efforts basis, without the assistance of external legal counsel.

- In its reply to our preliminary report, which was prepared with the assistance of external legal counsel, Compu-Finder acknowledged that it had used both an in-house software tool and commercial address harvesting software to collect 170,000 e-mail addresses from the Internet between November 2012 and February 2014.

- Compu-Finder developed a simple in-house software tool that would seek examples of the "@" symbol within websites of companies it had targeted as potentially being interested in its courses. The tool would then copy the associated e-mail addresses into an Excel spreadsheet to be filtered for quality assurance purposes.

- In terms of commercial address harvesting software, Compu-Finder indicated that it used "Email Extractor Plus", "Atomic Email Hunter", and, very briefly, "Business Email Extractor", all of which can be used to search websites by using key words and location filters.

- The organization explained that by initiating searches using key words such as "annuaire d'entreprises Québec" [company directory Quebec], it obtained "raw" output of URL and e-mail addresses which were then exported to an Excel spreadsheet to also be filtered for quality assurance purposes.

- Compu-Finder stated that of the 170,000 such e-mail addresses collected between November 2012 and February 2014 through address harvesting software, there remained approximately 28,000 addresses in three separate lists within its August 25, 2014 database after it had culled its database in anticipation of the coming into force of CASL.

- Compu-Finder clarified that, as of February 2015, these three lists were no longer in use. However, the addresses remained within its database, since it believed that there were many that could lawfully be used in the future under CASL.

- Compu-Finder maintained that it ceased to use address harvesting software before the address harvesting provisions set out in s. 7.1(2) of the Act came into force on July 1, 2014. Compu-Finder argued that s. 7.1(2) should not be applied retroactively to addresses collected prior to July 1, 2014.

Consent

Express consent

- Compu-Finder explained that its collection of e-mail addresses and the form of consent obtained to use the addresses for the purposes of sending commercial e-mails depended on the method of collection and the time period over which the lists were compiled.

- It claimed that the e-mail addresses that it collected directly from individuals or through telemarketing were obtained through express consent.

- We examined the database lists provided to the CRTC and noted discrepancies between their content and Compu-Finder's written representations with respect to the form of consent.

- Compu-Finder stated that it collected e-mail addresses solely by means of implied consent between April 2012 and April 2014. However, the approximate 29,000 e-mail addresses within the fourteen lists collated over this period were recorded in the database as having been collected by means of implied and express consent.

- We were later informed by counsel that some of the addresses had been mistakenly labeled as collected by means of "express consent" by Compu-Finder where it believed it had implied consent to collect and use such addresses under CASL's provisions, or was otherwise exempt from the need to obtain such consent under the business-to-business exemption available under the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations.Footnote 18

- Our review found that Compu-Finder's database lacked crucial details regarding how consent was obtained in each case. For instance, the database did not indicate the source from which an e-mail address was obtained and did not record details regarding consent, including the date express consent was provided (if applicable) or in which manner consent was obtained.

- To attempt to validate Compu-Finder's claims to have obtained express consent, we sent the organization a list of five e-mail addresses taken from its database,Footnote 19 which it had identified as being collected by means of express consent (e-mail addresses "A" to "E"). We asked Compu-Finder to state how and on what date it obtained the express consent of the individuals concerned and to provide written evidence of such consent.

- Compu-Finder claimed that consent was: (i) obtained for e-mail addresses "A" to "C" through client invoices; and (ii) obtained for e-mail addresses "D" and "E" through telemarketing calls in 2010 and 2014 respectively.

- Compu-Finder was unable to provide any written evidence of express consent being obtained for any of the five addresses. The copies of client invoices it provided in respect of e-mail addresses "A" to "C", while being for the correct third party organizations, were for completely different individuals from those organizations who had attended Compu-Finder training courses.

- No dates or written evidence of express consent was provided for the individuals who were allegedly called in 2010 and 2014. The only evidence presented for the existence of consent for the collection and use of e-mail addresses "D" and "E" supported the withdrawal of consent by the individuals concerned, not the original consent for the collection and use of their e-mail addresses.

- Following Compu-Finder's representations on consent, we interviewed five individuals who had made submissions and reports to the SRC concerning Compu-Finder promotional e-mails and who Compu-Finder claimed had provided express consent for the collection and use of their e-mails. The interviewees included the four individuals who used business e-mail addresses "A", "B", "D" and "E" above (we could not contact the individual using e-mail address "C") plus a fifth individual.Footnote 20

- All five interviewees confirmed that they had no previous dealings with Compu-Finder.

- The individual using e-mail address "A" made seven reports to the SRC between October 1, 2014 and October 7, 2014.Footnote 21 He indicated that Compu-Finder had sent him many unsolicited commercial e-mails before he commenced sending reports to the SRC. He did not recall ever having any dealings with Compu-Finder.

- The individual using e-mail address "B" made forty-five submissions and reports to the SRC between August 2014 and February 2015, which represented approximately 75% of the unsolicited e-mails he received from Compu-Finder. He confirmed that his e-mail address was publicly listed on his employer's website. He stated that he had never dealt with Compu-Finder before and had never attended any of its training courses.

- The individual using e-mail address "D" made two reports to the SRC on September 4 and October 9, 2014. The individual stated that he had received unsolicited e-mails prior to the coming into force of CASL as well. He stated that he had never provided express consent to Compu-Finder to collect and use his e-mail address. He confirmed that his colleagues also received e-mails and all their e-mail addresses were featured on their business' website.

- The individual using e-mail address "E" made two reports to the SRC on August 26 and 28, 2014. He indicated that he had records relating to his receipt of unsolicited commercial e-mails from Compu-Finder dating from February 2014. He stated that he would not avail himself of their courses as he did not understand or speak French. He further explained that in July 2014, he had added a non-solicitation message to his website's contact page clarifying that his e-mail address was provided solely so that customers could contact him and not for other purposes.

- The individual also contested Compu-Finder's assertion that it had obtained express consent to collect and use his business e-mail address through telemarketing in 2010. He explained that this was not possible as he was employed elsewhere and had a different e-mail address at the time. He did not acquire his present e-mail address until September 2012.

- A fifth individual made seven reports to the SRC between August 26 and September 29, 2014. A regional agent for an Ontario office of an insurance company, he indicated that he had never provided his e-mail address to Compu-Finder. On reviewing the individual's presence on Compu-Finder's database, we found he was listed in the July 2, 2014, database but absent from the later one. However, all 7 reports made to the SRC were regarding e-mails sent to him after the purported removal of his e-mail address from the August database.

- We also interviewed three individuals whose e-mail addresses were not in Compu-Finder's database, notwithstanding the fact that they reported receiving e-mails from Compu-Finder during the time period in which the database was in use.Footnote 22

- One individual made three reports to the SRC between October 10 and October 17, 2014. The individual reported that he had received e-mails from Compu-Finder for two to three months. He indicated that he was located in BC, had never had any dealings with Compu-Finder and was unlikely to avail himself of Compu-Finder's courses in the province of Québec.

- Two more individuals collectively made fifteen reports to the SRC between August 21 and September 25, 2014. Both individuals work at the same university in Ontario, although in different faculties. Both indicated that they had never provided their e-mail addresses to Compu-Finder. One individual stated that it was unlikely that he would avail himself of their French-language training courses. Both assumed that Compu-Finder had collected their e-mail addresses from the university's website.

- Compu-Finder explained that in May and June 2014, it sent approximately 100,000 e-mails to the addresses listed in its database. It did so to obtain recipients' express consent to its ongoing mailing of e-mails promoting its training courses. Compu-Finder confirmed that it received consent from approximately 360 individuals as a result of the campaign: a response rate of less than 0.004%.

Implied consent and exceptions to consent

- Compu-Finder indicated that it had also relied upon either implied consent or exceptions to the consent requirement to collect and use e-mail addresses from websites and other sources. Compu-Finder stated that for "most cases" it was relying on the "business-to-business" exemption contained within section 3 of the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations made under CASL, to send e-mails promoting its courses.Footnote 23 Compu-Finder asserted that it was permitted by this exemption to send e-mails to employees if it had a contractual relationship with the employer or if it had a history of correspondence with the recipient.

- Compu-Finder also claimed that organizations had conspicuously published employees' contact information, including e-mail addresses, and that these e-mail addresses were not accompanied by non-solicitation statements. Compu-Finder asserted that in collecting these e-mail addresses and sending its promotional e-mails to individual users of these e-mail addresses, it could rely on paragraph 10(9)(b) of CASL as well as the exception for publicly available information in paragraphs 7(1)(d) and 7(2)(c.1) of PIPEDA.Footnote 24

- Compu-Finder further stated that, pursuant to clause 4.3.6 of Schedule 1 of PIPEDA, it could rely on implied consent to collect the e-mail addresses because the addresses were non-sensitive personal information and were found on publicly available websites. Compu-Finder asserted that its e-mail messages were, in the majority of cases, relevant to the professional activities of the individual recipients of such messages.

- Compu-Finder stated that its interpretation was supported by inclusion of section 4.01 of PIPEDA, which provides that the Act does not apply to business contact information that is collected, used or disclosed solely for the purpose of communicating or facilitating communication with an individual in relation to their employment business or profession.

- Our analysis of the several websites of organizations whose employees' e-mail addresses are contained in Compu-Finder's database in significant numbers identified at least four websites that had non-solicitation statements alongside their staff directories.

- For example, one university website had stated since at least January 2013 that:

This online telephone directory is the exclusive property of McGill University. It may be used by the McGill community and the general public to search for the coordinates of McGill staff. Any unauthorized use of this information, including bulk e-mail activity (spam) or commercial purposes, is strictly prohibited.Footnote 25

- In another instance, a college in Quebec had stated since March 2014 that:

[Translation]

This telephone directory is the property of the Cégep de Sherbrooke. Any use of the directory for the purpose of selling goods or services or for solicitation of any kind is strictly prohibited.Footnote 26 - Although Compu-Finder stated that, in the majority of cases, it sent e-mails that were relevant to a recipient's professional activities, we noted that its marketing databases from July 2, 2014 and August 25, 2014, contained no information about a person's role, title or responsibilities. The excel spreadsheet used to record management e-mail addresses collected by Compu-Finder's telemarketing agents from April 2014, only listed individuals under generic titles, such as "Dir HR", "President", "Assistant/VP" and "Finance" and not their specific role or responsibilities.

- Furthermore, we noted that Compu-Finder sent the same promotional e-mails to individuals regardless of their organization's business, or their specific roles, functions and responsibilities. The same promotional e-mails were also sent to many individuals' personal e-mail addresses and to generic business e-mail addresses, where the recipient's business, roles and responsibilities could not be readily ascertained.

- For example, the individual using e-mail address "A" was sent e-mails promoting training courses on construction and cities and for finance directors, although he was a computer science professor at a university. The individual using e-mail address "B" was sent e-mails promoting training courses on how to measure the profitability of his business despite being a scientist working for a government agency. The individual using e-mail address "D" was sent an e-mail promoting a training course on how to be an excellent group leader although he was a self-employed bookkeeper. The eighth individual we interviewed (see paragraph 87 above) was sent e-mails promoting training courses on how to be a better administrative assistant despite being a social sciences professor at a university.

Compu-Finder's new contact management system

- Compu-Finder admitted that its databases were not adequately structured and that it required manual intervention to find information on specific records.

- It explained that it was in the process of improving its contact management system to include: (i) any exemption applicable concerning the need to obtain consent applicable under CASL or PIPEDA (with supporting documents and notes); and (ii) whether it has obtained express or implied consent (with the type of consent, the date obtained, the completed application with identification of the contact address).

- Compu-Finder was confident that the new contact management system would ultimately contain all the information and necessary documentation needed with regards to obtaining and proving consent and the application of consent exemptions.

Accountability

- During the investigation, Compu-Finder admitted that it did not have a designated individual accountable for the organization's compliance with its privacy obligations under the Act.

- Furthermore, Compu-Finder admitted that it did not have a written privacy policy or equivalent content within its Terms of Service or other material, because it was unaware that it was obliged to have such a policy.

- We also asked for a copy of the organization's internal privacy manual or privacy procedures, including those related to its collection and use of e-mail addresses. Once again, Compu-Finder explained that it did not have any manual or procedures dealing with privacy matters.

Openness

- In addition to the accountability matters noted above, we examined both the prosperer website and the academie website. The prosperer website had no privacy policy. At the bottom of the academie website's home page, we noted a link entitled "Confidentialité" [Confidentiality]. However, upon clicking on the link we were taken to a page of the website with just the heading and no content. We could find no other material within either website that provided access to any privacy-related information for consumers or businesses.

Analysis and Findings

Personal information

- The first issue to consider is whether Compu-Finder is collecting and using personal information. Prior to June 18, 2015, section 2 of the Act defined personal information as information about an identifiable individual, but did not include, the name, title or business address or telephone number of an employee of an organization.

- Our investigation revealed that Compu-Finder collects both individuals' personal e-mail addresses and individual's business e-mail addresses. It used such addresses to send commercial e-mails promoting its training courses until it introduced a temporary moratorium in April 2015.

- In PIPEDA Case Summary #2005-297: Unsolicited e-mail for marketing purposes, the then Assistant Privacy Commissioner concluded that as a business e-mail address was not specified in section 2 of the Act, as it existed at the time, it was an individual's personal information for the purposes of the Act.Footnote 27

- On June 18, 2015, the Digital Privacy Act, amended the definition of personal information in the Act by eliminating the exception for contact information related to employees. As such, under either the old or new definitions of personal information, the e-mail addresses collected by Compu-Finder are considered "personal information" under the Act.

- The Digital Privacy Act also amended the scope of PIPEDA by introducing a new subsection 4.01 such that the collection, use or disclosure of "business contact information" will not be covered under the Act in certain circumstances. Business contact information is defined to include a "work electronic address" such as a business e-mail address. However, the carve-out provided by section 4.01 only applies where an organization collects, uses or discloses business contact information of an individual "solely for the purposes of communicating or facilitating communication with the individual in relation to their employment, business or profession."

- However, our investigation leads us to conclude that many of the commercial e-mails sent by Compu-Finder are not relevant to the employment, business or profession of the e-mail recipients. In particular, as noted in paragraphs 97 and 98, we identified a number of e-mail messages that had been sent by Compu-Finder where the messages were not relevant to the recipient's employment, business or profession. We also note that Compu-Finder's database did not record an individual's position or title so as to allow it to determine whether a message would be "relevant" to that individual's employment, business or profession.

- As a result of the above, we are of the view that Compu-Finder is collecting and using personal information and that PIPEDA continues to apply to Compu-Finder's activities in this respect.

Collection and consent

The relevance of CASL

- In its representations, Compu-Finder referred to provisions of CASL relating to the sending of commercial electronic messages, and regulations made thereunder, as justification for its practices. In our view, these provisions, while similar in some respects to those found in the Act, are not directly relevant to our investigation, which was focused on Compu-Finder's compliance with PIPEDA. We have therefore not considered such provisions further in our analysis, except with respect to the amendments CASL made to the Act regarding address harvesting.

Express consent

- The express consent allegedly obtained by Compu-Finder to collect and use e-mail addresses to send its commercial e-mails raises multiple concerns.

- Principle 4.3 of Schedule 1 of the Act states that the knowledge and consent of the individual are required for the collection, use, or disclosure of personal information, except where inappropriate.

- Principle 4.3.2 states that organizations shall make a reasonable effort to ensure an individual is advised of the purposes for which the information will be used. To make the consent meaningful, the purposes must be stated in such a manner that the individual can reasonably understand how the information will be used or disclosed. Similarly, Principle 4.2 states that the purposes for which personal information is collected shall be identified by the organization at or before the time the information is collected.

- Compu-Finder stated that it informed individuals of the purposes of collecting their addresses, i.e. to send them information about the organization's training courses. Such notification is required by Principles 4.2 and 4.3.2 of Schedule 1 of the Act.

However, the telemarketing script used by Compu-Finder, at least between April 2014 and March 2015, did not adequately inform individuals about the purposes for which it sought to collect their e-mail addresses, even when agents were pressed for more information. Nor did the telemarketing agents direct individuals to where such purposes could be found, e.g. to a website privacy policy (which in fact did not exist). We are of the view, therefore, that Compu-Finder contravened Principles 4.2, 4.3 and 4.3.2. - Principle 4.4 requires that personal information be collected by "fair and lawful means". Principle 4.4.2 states that the requirement that personal information is collected by fair or lawful means is intended to prevent organizations from collecting information by misleading or deceiving individuals about the purpose for which the information is being collected.

- In this case, the script used by the telemarketing team implied that Compu-Finder already had a business-to-business relationship with the manager or director approached, and that the collection of the e-mail address was simply for administrative purposes rather than for use in sending promotional e-mail communications.

- By seeking to collect such information from third parties, e.g. administrative staff, rather than directly from the individuals concerned, and by not revealing the fact that in many instances, the call was to obtain personal information for marketing purposes, we believe that Compu-Finder collected personal information in contravention of Principle 4.4 of Schedule 1.

- Furthermore, when we sought to validate the consent obtained, Compu-Finder's claims of obtaining express consent from specific individuals could not be supported by any documentary evidence whatsoever. Indeed, Compu-Finder's assertions of express consent were directly contradicted and refuted by individuals that we interviewed.

- Compu-Finder claimed that with a small, new, telemarketing team and in the space of only four months it collected approximately 38,000 e-mail addresses through means of express consent. With a conversion rate of 80%, this would mean over 48,000 calls made. We are of the view that this number of calls and the conversion rate are neither credible nor arguably possible. Indeed, in the absence of any privacy procedures or practices, we question whether the Compu-Finder employees seeking consent properly understood and applied the concept as contemplated under the Act.

- In addition, the absence of a written privacy policy on Compu-Finder's websites calls into question the validity of the consent Compu-Finder claims to have when individuals seek to engage it by indicating an interest in its Club Connoisseur program, wishing to receive its newsletter, or making a general inquiry about its services and courses. For consent to be meaningful, it requires that individuals be informed about an organization's purposes for collecting personal information. In the absence of a privacy policy or other easily accessible information about Compu-Finder's practices it is difficult to see how this requirement is met.

- Taking into account all of the above, we are of the view that Compu-Finder has not obtained meaningful express consent to collect and use individuals' e-mail addresses obtained via telemarketing or directly from individuals and is therefore in contravention of Principles 4.2, 4.3, 4.3.2 and 4.4 of Schedule 1 of the Act.

Implied consent

- Principle 4.3.6 states that the way in which an organization seeks consent may vary, depending on the circumstances and the type of information collected. An organization should generally seek express consent when the information is likely to be considered sensitive. Implied consent would generally be appropriate when the information is less sensitive.

- In addition to express consent, Compu-Finder stated that it collected and used e-mail addresses from some organizations as a result of implied consent, due to existing business relationships or the open publication of e-mail addresses.

- Such business relationships can exist between a training provider and an individual, where for example, the individual has attended a training course, sought to register for a course, has made prior inquiries about courses or purchased training course material. Likewise, a relationship between a training provider and an organization can arise for example, where an organization has funded such training for its employees.

- When we asked for evidence of the consent obtained for three individuals, Compu-Finder pointed to its client invoices. The invoices provided were for different employees. By providing these invoices, Compu-Finder seemed to imply that even if a few employees of an organization attended its training courses, its existing business relationship with the organization allows it to send commercial e-mails to all of the organization's other employees without restriction.

- In our view, under PIPEDA, Compu-Finder cannot rely on the mere fact that an individual in an organization may have attended one of its training courses to collect and use the e-mail addresses of other individuals in that organization for marketing purposes. Collecting and using the e-mail addresses of individuals who have had no dealings with Compu-Finder is outside of their reasonable expectations and therefore, cannot form the basis for meaningful consent under principle 4.3.

- Compu-Finder pointed to the fact that many of the e-mail addresses it had collected were available online and that business e-mail addresses were non-sensitive in nature. However, e-mail addresses may be posted online for many different purposes and it cannot be assumed that those individuals or organizations posting addresses would reasonably expect to receive commercial offers.

- By way of example, individuals may solicit feedback from people interested in the subject of a blog they have written, a community group may wish to facilitate contact amongst its members to organize events, and charitable organizations may do so to obtain donations. Commercial organizations may include employee e-mail addresses on a contact page or staff directory to facilitate sales, to provide technical support, to resolve consumer complaints or to obtain customer feedback.

- The Act provides that an organization may collect and use personal information without consent if it is "publicly available" and is specified in the Regulations. Paragraph 7(1)(d) states that an organization may collect personal information without the knowledge and consent of an individual only if the information is publicly available and is specified by the Regulations. Paragraph 7(2)(c.1) states that an organization may, without the knowledge and consent of the individual, use personal information only if it is publicly available and is specified by the Regulations.

- Section 1 of the Regulations states that certain information and classes of information are specified as "publicly available" for the purposes of paragraphs 7(1)(d), 7(2)(c.1) and (3)(h.1) of the Act. This includes , among others:

1(b) personal information including the name, title, address and telephone number of an individual that appears in a professional or business directory, listing or notice, that is available to the public, where the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information relates directly to the purpose for which the information appears in the directory, listing or notice. [Emphasis added]

- In PIPEDA Case Summary #2005-297: Unsolicited e-mail for marketing purposes, the then Assistant Privacy Commissioner concluded that a respondent's collection and use of personal information to market the sales of sports tickets was not related to the purposes for which the employer (a law firm) made its employees' contact information publicly available to its clients and potential clients. Therefore, the Regulations did not authorize the collection and use of this information by the respondent organization without consent.

- During our investigation, we found instances where Compu-Finder sent e-mails marketing its training courses to individuals where their e-mail addresses had been posted for entirely different reasons.

- Individuals we interviewed who were academic staff had received e-mails from Compu-Finder in the absence of any existing relationship or consent to do so. Their e-mail addresses were made publicly available on their university's website for the purposes of being contactable by students and for other university business. In another instance, an insurance agent's e-mail address was publicly posted by his employer, along with other agents' addresses, so that they could be contacted by potential clients and policyholders.

- In addition, we also found examples where organizations had explicitly and prominently stated that the e-mail addresses listed on their websites were not to be used for commercial purposes. Yet, Compu-Finder continued to send promotional e-mails to individuals working for these organizations and did not appear to conduct appropriate due diligence of its database records after the publication of such statements.

- Compu-Finder asserted that, in the majority of cases, its e-mails were relevant to the professional activities of the recipients. However, as noted above, in the e-mails we examined we found that this was not the case and that Compu-Finder did not have a means of knowing when a particular message would be relevant to an individual's activities.

- These examples demonstrate that, in many instances, Compu-Finder is not able to rely on implied consent under PIPEDA, or rely on the Regulations to authorize the collection and use of e-mail addresses without consent under PIPEDA's "publicly available" exemption, in contravention of Principle 4.3.

- Even if the e-mail addresses could be considered "publicly available", we note that Compu-Finder would not be entitled to rely on this exemption for the e-mail addresses it obtained through the use of address harvesting software pursuant to paragraphs 7.1(2) of the Act.

- Paragraphs 7.1(2)(a) and (b) state that paragraphs 7(1)(a), (c) and (d) and (2)(a) to (c.1) and the exception set out in clause 4.3 of Schedule 1 do not apply in respect of: (a) the collection of an individual's electronic address, if the address is collected by the use of a computer program that is designed or marketed primarily for use in generating or searching for, and collecting, electronic addresses; or (b) the use of an individual's electronic address, if the address is collected by the use of a computer program described in paragraph (a).

- In our view, while the collection of e-mail addresses via address harvesting software occurred (and ceased) before s. 7.1(2) of the Act came into force, the 28,000 e-mails collected via this software remained in its database for e-mail marketing purposes after July 1, 2014 and were, according to Compu-Finder, used until February 2015. As a result, pursuant to paragraph 7.1(2)(b) Compu-Finder would not be able to rely on the "publicly available" exemption under paragraph 7(2)(c.1) to send e-mail marketing messages to these particular e-mail addresses going forward.

Accountability

- Principle 4.1 states that an organization is responsible for personal information under its control and shall designate an individual or individuals who are accountable for the organization's compliance with the principles.

- Compu-Finder admitted that it did not have a designated individual within the organization accountable for its privacy compliance obligations.

- Principle 4.1.4 states that an organization shall implement policies and practices to give effect to the principles, including: (a) implementing procedures to protect personal information; (b) establish procedures to receive and respond to complaints and inquiries; (c) training staff and communicating to staff information about the organization's policies and practices; and (d) developing information to explain the organization's policies and procedures.

- Compu-Finder disclosed that it did not have a written privacy policy or any equivalent document containing privacy content. This was confirmed when our Office could not find any privacy policy on the prosperer.ca website and also when we went on the academie website's home page, clicked on the "Confidentialité" [Confidentiality] tab and found an empty page.

- Compu-Finder stated that it would designate a privacy officer and introduce written privacy policies and procedures to comply with the Act, if it was required to do so.

Openness

- Principle 4.8.1 requires organizations to be open about their policies and practices with respect to the management of personal information. Individuals shall be able to acquire information about an organization's policies and practices without unreasonable effort. This information shall be made available in a form that is generally understandable.

- Principle 4.8.2 states that the information made available by an organization shall include: (a) the name or title, and the address, of the person who is accountable for the organization's policies and practices and to whom complaints or inquiries can be forwarded; (b) the means of gaining access to personal information held by the organization; (c) a description of the type of personal information held by the organization, including an account of its general use; (d) a copy of any brochures or other information that explain the organization's policies, standards, or codes; and (e) what personal information is made available to related organizations (e.g., subsidiaries).

- In the absence of any public privacy policy or procedures, any internal policies and procedures which might be disclosed to individuals in the absence of such public-facing documents, or contact details as to how to obtain information on privacy issues, individuals cannot easily and readily acquire access to information about the organization's personal information management practices.

- Further, it is highly unlikely, given the absence of an internal privacy policy and procedures, that Compu-Finder personnel are properly informed in the key privacy concepts, such as consent, to be able to appropriately inform such individuals of the organization's privacy practices in a manner compliant with the Act. The absence of an employee designated as responsible for ensuring the organization complies with its privacy obligations, also means that personnel do not have anyone they can turn to, to assist and guide them when communicating with individuals regarding privacy-related matters. Compu-Finder is, therefore, also non-compliant with principles 4.8.1 and 4.8.2.

Recommendations

- In our preliminary report, our Office made recommendations that Compu-Finder:

- Designate an individual within the organization to be responsible for its compliance with the Act;

- Develop and implement a written privacy policy and procedures regarding the organization's collection, use, disclosure, protection, retention and destruction of personal information, how individuals' can obtain access to the personal information held by the organization and to receive and respond to privacy inquiries and complaints;

- Publish its privacy policy in a form that is easily accessible and generally understandable to members of the public;

- Train employees and communicate to them information about the organization's privacy policy and procedures;

- Amend its telemarketing script to provide: a clearer explanation of Compu-Finder's business; the purpose of its call; why it wishes to collect the e-mail address; to what use such addresses will be put; and how individuals called can obtain more information about their privacy rights;

- Maintain appropriate records and evidence of all implied and express consent it obtains from individuals and organizations and when such consent is withdrawn;

- Only collect and use e-mail addresses of individuals for marketing purposes with proper consent or pursuant to a valid exception under the Act;

- Destroy e-mail addresses in its possession which were collected without obtaining consent or pursuant to a valid exception under the Act; and

- Refrain from collecting any electronic addresses of individuals in the future, through the use of a computer program that is designed or marketed primarily for use in generating or searching for, and collecting such addresses.

- In addition to the nine recommendations above, we further recommended that Compu-Finder commission an independent, third-party audit of its privacy programs after having implemented the compliance measures. We also asked it to provide an unedited copy of the independent auditor's final report and its response to any audit recommendations within nine months of the date of our report of findings.

Compu-Finder's response to our recommendations

- Notwithstanding Compu-Finder's previously stated positions, it agreed to implement measures to address all of the recommendations outlined in our preliminary report on a "without prejudice and without admission" basis.

- Compu-Finder amended its telemarketing script to address the concerns of our Office stated in recommendation e). It now explains more clearly the nature of its business and the purposes for its calls and collects contact details only where an individual or organization specifically requests that Compu-Finder send information regarding its training services via e-mail.

- Compu-Finder also implemented measures to address recommendations a) and b) before the issuance of this report of findings.

- Compu-Finder agreed to implement measures to address recommendations c) and d) within three months of the date of issue of our report of findings and implement measures to address recommendations f) to i) within four months of the date of issuance of our report of findings.

- It also agreed to commission a third-party audit of its privacy programs and provide an unedited copy of the auditor's final report and its response to the audit recommendations within eight and nine months of the date of issuance of our report of findings respectively.

Conclusion

- Taking into account the above, we have determined that the matters relating to recommendations a), b) and e) are well-founded and resolved. The matters relating to recommendations c), d) and f) to i) are well-founded and conditionally resolved.

- Our Office has a continuing interest in ensuring that Compu-Finder implements the measures needed to bring it into full compliance with the Act. As such, our Office will be closely monitoring the organization's implementation of our recommendations and has entered into a compliance agreement with Compu-Finder pursuant to subsection 17.1(1) of the Act.

Appendix A

Example of a promotional e-mail submitted by Compu-Finder to the CRTC on March 13, 2015

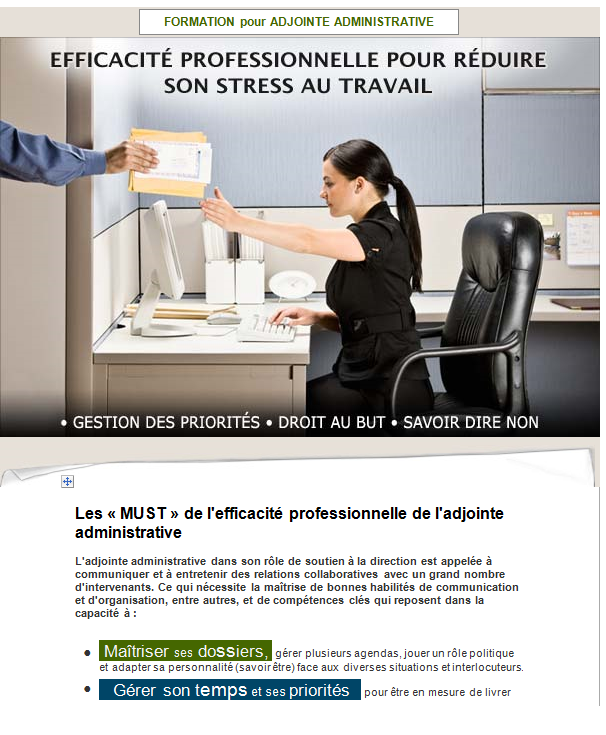

(Note: Image is available in French only. A text version in English is available under the image.)

Text version

This is an example of an electronic message sent by Compu-Finder to individuals promoting the company’s training services.

Image 1

Training for administrative assistants

Professional effectiveness to reduce work stress

- Managing priorities

- To the point

- How to say no

Image 2

The "MUST-DOs" for professional effectiveness for administrative assistants

In their management support role, administrative assistants are called on to communicate and maintain collaborative relationships with a large number of stakeholders. They need to have good communication and organizational skills, as well as the following key competencies:

- Ability to manage files, juggle different agendas, play a political role and adapt their personality (personal style) to a wide variety of situations and clients;

- Ability to manage time and priorities to be able to deliver high-quality work on time and on deadline;

- Ability to maintain effective and professional relationships with everyone they deal with: managers, co workers, clients, suppliers, etc.

- Ability to be productive in their work, in relationships with others (both in the course of their job duties and in meetings or gatherings), in organizing their work and in using appropriate tools and technologies.

Are you often disrupted in your work?

Do you sometimes have difficulty meeting your professional commitments?

Do you feel under-equipped?

Could your relationships be more cordial, and your work environment more relaxed?

How can you reduce pressure and manage your stress more effectively?

This training is for you.

Register now. Spaces are limited.

1-877-726-2238

Dates and locations

Montreal region: February 3, 4 and 5, 2015

Hotel Le Crystal | 1100 De la Montagne Street, Montreal

Quebec City region: February 13, 14, and 15, 2015

Lévis Convention and Exhibition Centre| 5750 J-B-Michaud Street, Lévis

You have received this email by virtue of the position you have within your company.

ACF Management would like to send you relevant information from time to time to help you succeed in your professional and personal projects.

Edit your interests/Unsubscribe

Mailing address: 707 Du Village Road, Morin Heights, QC J0R 1H0

Appendix B

Sample of submissions/reports made against Compu-Finder to the SRC

- July 1, 2014, to September 10, 2014

| E-mail address (Note: Email addresses have been removed from the web copy of this report to protect individuals’ personal information) |

Date of submission or report to SRC | Province of recipient | Entry in Compu-Finder database - July 2, 2014 or Aug. 25, 2014? |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| July 15 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| July 30 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| July 31 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 5 2014 | British Columbia | No | |

| Aug 7 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 7 2014 | Alberta | No | |

| Aug 22 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Aug 25 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 26 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Aug 26 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Aug 29 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 29 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 29 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 29 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Aug 31 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 1 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 2 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 3 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 3 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 4 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 8 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 9 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 9 2014 | Quebec | No | |

| Sep 10 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Sep 10 2014 | Ontario | No | |

| Sep 10 2014 | Quebec | No |

Appendix C

List of email addresses sent to Compu-Finder on April 8, 2015 for which we requested evidence of express consent:

| E-mail address (Note: Email addresses have been removed from the web copy of this report to protect individuals’ personal information) |

Block | Type of consent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 014_7-N | Express | |

| B | N-811-O | Implied & Express | |

| C | N-811-O | Implied & Express | |

| D | 014_9-N | Express | |

| E | Bloc-6_27-28-O | Express |

Appendix D

Compliance Agreement Between: The Privacy Commissioner of Canada and 3510395 Canada Inc.

WHEREAS the Privacy Commissioner of Canada ("the Commissioner") is responsible for the administration and enforcement of Part 1 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (the "Act"), which governs the collection, use or disclosure of personal information by organizations in the course of commercial activities;

AND WHEREAS on July 1, 2014, Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation ("CASL") amended the Act to include provisions specifically targeted at the harvesting of electronic addresses through means of computer programs;

AND WHEREAS 3510395 Canada Inc. ("Compu-Finder") is a federally-incorporated company based in Morin-Heights, Quebec, which offers professional training courses in Ontario and Quebec;

AND WHEREAS Compu-Finder sends e-mails promoting its professional training courses primarily directed to employees in organizations operating in the private, public and not-for-profit sectors in Quebec as well as in other provinces;

AND WHEREAS on November 28, 2014, the Commissioner initiated a complaint against Compu-Finder pursuant to s. 11(2) of the Act, on the basis that there were reasonable grounds to investigate Compu-Finder's collection and use of individuals' e-mail addresses for the purpose of sending e-mails promoting its business activities;

AND WHEREAS the Commissioner, based on his investigation, found that Compu-Finder has contravened several provisions of Division 1 of Part 1 of PIPEDA as follows:

- Compu-Finder does not have a designated individual within the organization accountable for its compliance with the requirements of Part 1 of the Act in contravention of Principle 4.1 of Schedule 1 of the Act;

- Compu-Finder does not have any written policies or procedures to give effect to the principles in Schedule 1 of the Act, in contravention of Principle 4.1.4;

- Compu-Finder has not made available information about its policies and practices with respect to the management of personal information in contravention of Principles 4.8.1 and 4.8.2 of Schedule 1 of the Act;

- Compu-Finder engaged in telemarketing using a script that did not adequately inform individuals about the purposes for which it was seeking to collect their e-mail addresses, in contravention of Principles 4.2, 4.3, 4.3.2 and 4.4 of Schedule 1 of the Act;

- In many instances, Compu-Finder could not establish that it had obtained express or implied consent to collect and use individuals' e-mail addresses (or otherwise adequately ensure that an exemption to such consent requirement was applicable), in contravention of Principle 4.3 of Schedule 1 of the Act;

- Compu-Finder collected approximately 170,000 e-mail addresses through the use of e-mail address harvesting software between November 2012 and February 2014; and

- A subset of such e-mail addresses (approximately 28,000) remain in its database and were used to send commercial e-mails until February 2015 notwithstanding the restrictions imposed by s. 7.1(2) of the Act, as amended by CASL, on the use of e-mail addresses collected by means of address harvesting software.

AND WHEREAS in a report of findings concerning the complaint initiated by the Commissioner on November 28, 2014 ("Report of Findings") the Commissioner made several recommendations to Compu-Finder to ensure Compu-Finder's compliance with the Act;

AND WHEREAS Compu-Finder acknowledges the Commissioner's findings as set out in the Report of Findings and, without any admission as regards the veracity of the claims and arguments set out in the Report of Findings (including those summarized above), agrees to fully implement the Commissioner's recommendations in order to bring itself into compliance with the Act;

AND WHEREAS the Parties agree that while entering into this Agreement is voluntary, once entered into, it binds the parties to the obligations herein and failure to comply can trigger the application of s. 17.2 of the Act;

NOW THEREFORE, pursuant to ss. 17.1 and 17.2 of the Act, the Commissioner and Compu-Finder hereby agree as follows:

I. INTERPRETATION

- For the purpose of this Agreement, the following definitions shall apply:

- "Act" means the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C. 2000, c. 5;

- "Agreement" means this Compliance Agreement entered into by Compu-Finder and the Commissioner pursuant to s. 17.1 of the Act;

- "CASL" means An Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act, S.C. 2010, c.23

- "Commissioner" means the Privacy Commissioner of Canada appointed pursuant to s. 53(1) of the Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21 and his authorized representatives;

- "Compu-Finder" means 3510395 Canada Inc.;

- "Parties" means the Commissioner and Compu-Finder;

- "Report of Findings" means the report issued by the Commissioner to Compu-Finder pursuant to s. 13 of the Act in respect of the complaint initiated by the Commissioner on November 28, 2014.

II. REMEDIAL MEASURES

- In order to address the Commissioner's recommendations contained in the Report of Findings, Compu-Finder shall, in addition to any measures it has already taken:

- ensure that there exists an individual within the organization who has been designated as accountable for Compu-Finder's compliance with the Act;

- develop and implement a privacy policy and procedures regarding: (i) Compu-Finder's collection, use, disclosure, protection, retention and destruction of personal information; (ii) how individuals can obtain access to the personal information held by Compu-Finder; and (iii) to receive and respond to privacy inquiries and complaints within 2 months of the Report of Findings being issued;

- publish its privacy policy in a form that is easily accessible and generally understandable to members of the public within 3 months of the Report of Findings being issued;

- train employees and communicate to them information about Compu-Finder's privacy policy and procedures within 3 months of the Report of Findings being issued;

- for all telemarketing calls involving the collection of e-mail addresses for marketing purposes, continue to use the amended telemarketing script provided to the Commissioner's office on September 25, 2015 and entitled "SCRIPT5_Spécialiste en dévéloppement des compétences_230615" or an alternative script which provides a clear explanation of Compu-Finder's business; the purpose of its call; why it wishes to collect the e-mail address; to what use such addresses will be put, and how individuals called can obtain more information about their privacy rights;

- maintain appropriate records and evidence of all implied and express consent it obtains from individuals (and/or evidence that an exception to the consent rule is applicable under the Act) and, as the case may be, when such consent is withdrawn, within 4 months of the Report of Findings being issued;

- henceforth, only collect and use e-mail addresses of individuals for marketing purposes with proper consent, or pursuant to a valid exception under the Act;

- destroy e-mail addresses in its possession which were collected without obtaining consent or pursuant to a valid exception under the Act, within 4 months of the Report of Findings being issued;

- refrain from collecting any electronic addresses of individuals in the future, through the use of a computer program that is designed or marketed primarily for use in generating or searching for, and collecting such addresses;

- commission an independent, third-party audit of its privacy programs within 8 months of the Report of Findings being issued. In this regard, Compu-Finder undertakes to engage an appropriately experienced, qualified and independent third party to review Compu-Finder's privacy practices and procedures as specified in paragraphs a) to h); and

- provide an unedited copy of the independent auditor's final report and any response by Compu-Finder to the audit's recommendations within 9 months of the Report of Findings being issued.

III. COMPLIANCE REPORTING, MONITORING AND ENFORCEMENT

- Compu-Finder shall confirm in writing to the Commissioner that it has implemented each remedial measure referred to in section 2 within 2 weeks after the measure has been implemented in accordance with the prescribed timeline. Compu-Finder shall include sufficient details and supporting documentary and electronic evidence to establish that it has complied with the Agreement, such as copies of its privacy policies and procedures, training material, and examples of records kept under Compu-Finder's new contact management system.

- The Commissioner may, at his discretion and from time to time, request information and documents from Compu-Finder for the purpose of verifying its compliance with this Agreement.

- The Commissioner may also visit Compu-Finder's principal place of business for the purpose of verifying compliance with this Agreement at any time, subject to providing 10 days notice to Compu-Finder.