Review of the Personal Information Handling Practices of the Canadian Firearms Program

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Department of Justice Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Final Report

August 29, 2001

| AFO | Area Firearms Officer |

|---|---|

| CCRA | Canada Customs and Revenue Agency |

| CFC | Canadian Firearms Centre |

| CFO | Chief Firearms Officer |

| CFR | Canadian Firearms Registry |

| CFRO | Canadian Firearms Registry Online |

| CFRS | Canadian Firearms Registration System |

| CPIC | Canadian Police Information Centre |

| CPS | Central Processing Site |

| DOJ | Department of Justice Canada |

| FAC | Firearms Acquisition Certificate |

| FIP | Firearms Interest Police |

| FO | Firearms Officer |

| FRT | Firearms Reference Table |

| IT | Information Technology |

| LFO | Local Firearms Officer |

| MOU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| NPS | National Police Services |

| NPSN | National Police Services Network |

| OPP | Ontario Provincial Police |

| ORI | Originating Agency |

| OSR | Operational Statistical Reporting System |

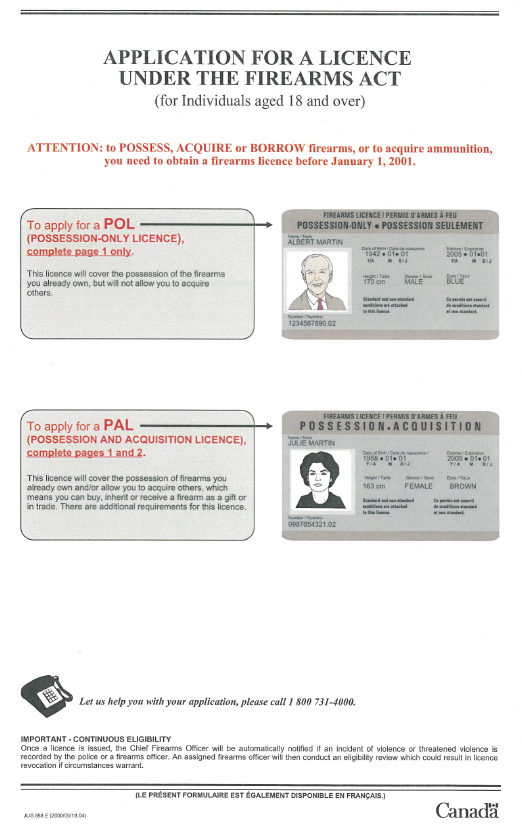

| PAL | Possession and Acquisition Licence |

| POL | Possession-Only Licence |

| PFO | Provincial Firearms Officer |

| PIRS | Police Information Retrieval System |

| QPS | Québec Processing Site |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| RWRS | Restricted Weapons Registration System |

| UCR | Uniform Crime Reporting |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

My predecessor and I have taken a keen interest in the Canadian Firearms Program since it was first proposed. This is because the Program involves the collection and use of large amounts of highly sensitive personal information. We identified a number of potential privacy problems when the concept was first proposed; we made suggestions when the legislation was before Parliament; and we have commented on the subsequent regulations. None of our suggestions was undertaken.

My Office has received a number of inquiries and complaints about the Program since it was first proposed, including some from Members of Parliament. In part to assist our Office in responding to these complaints and inquiries, we decided in September 1999 that it was an opportune time to review the Program. The review had three objectives: to learn how the Firearms Program functions; to assess its compliance with the basic fair information principles as set out in the Privacy Act; and to offer observations and recommendations to improve the operation of the Program from a privacy perspective.

This review, which was initiated in January 2000, was based primarily on visits to the Canadian Firearms Centre, the Canadian Firearms Registry, the Central Processing Site, and three Chief Firearms Officer sites (Ontario, Saskatchewan and Alberta).

The Canadian Firearms Centre web site states:

"The licensing and registration system is a reasonable and minor intrusion on personal privacy when weighed against the greater benefits to Canadian society. All information in the registration system will be strictly controlled and governed by access to information and privacy laws."

While gun control is important to the security of Canadians, the Program inevitably involves a significant intrusion on privacy. It requires the collection of a vast amount of personal information for purposes of the application and screening process. On the whole, our review has not found any egregious violations of the Privacy Act. We have found, however, a number of instances where the privacy of Canadians could be strengthened.

Our main concerns about the Firearms Program and our recommendations for corrective measures relate to three areas.

- Access and correction rights:

Canadians are finding it difficult and time-consuming to exercise their access and correction rights because of the multi-jurisdictional nature of the Program. A single point of access would resolve many of the related problems.

- Collection and use of personal information:

Firearms Officers have very broad powers and discretion to investigate and gather personal information about applicants. Access to police information should be tightened. Firearms Officers should only have access to information that is relevant to their duties.

- Intrusiveness of the questions on the firearms licence application form:

Much of the information collected in the application process-about mental health, job losses, bankruptcies, substance abuse, etc.-is highly intrusive. We have concerns about the breadth of the information captured as well as its usefulness in the decision-making process. In our view, the Program has not provided a "demonstrable need" for some of the personal information being collected on the firearms licence application form.

While our report also raises some issues relating to the disclosure of personal information and security measures, we found that the physical, personnel and information technology security measures are appropriate to the information being protected. With respect to the disposal of personal information collected by the Program, there are outstanding questions about how this will be done since no clear policies and procedures are in place.

In April 1997, following a Parliamentary Committee recommendation, the Minister of Justice undertook to negotiate information sharing agreements that would ensure that the federal Privacy Act would apply in cases where no provincial and territorial privacy legislation exists. However, these agreements are still not in place. Overall co-ordination has been difficult given, among other things, the multi-jurisdictional nature of the Canadian Firearms Program. The absence of information sharing agreements has resulted in ongoing disputes relating to "ownership and control" of the records among the various partners and levels of government involved in the administration of the Program.

By and large, Program officials were helpful and co-operative during the course of the review and expressed interest not only in the review's objective but also in the application of the Privacy Act. In some cases, remedial action has already been initiated.

It should also be noted that this review does not address the following issues that have arisen subsequent to the research and field work that form the basis of this report (see Appendix H):

- the personal information handling practices of the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency;

- the outsourcing issues; and

- any international information sharing agreements.

George Radwanski

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

REVIEW

BACKGROUND

Bill C-68, An Act respecting firearms and other weapons, (the Firearms Act) was introduced in February 1995 and received Royal Assent on December 5, 1995. The Firearms Act is a highly controversial piece of legislation that produces strong emotions among both its supporters and its critics. Our Office's interest in the legislation is simple; the Firearms Program involves the collection and use of large amounts of highly sensitive personal information.

Following the introduction of the Bill, our Office raised several concerns regarding the legislation and the implementation of the Firearms Program. On November 2, 1995 during an appearance before the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, the former Privacy Commissioner indicated that:

- the Bill, or the regulations under it, may well need to impose additional restrictions regarding collection in light of the sensitivity of the information;

- the Bill should state clearly that such information falls under the protective umbrella of the Privacy Act; or at least as part of the Agreements between the federal and provincial governments; and that

- the Bill should state somewhere in the legislation that the Privacy Act applies to all of the information collected no matter where it is held.

Then, on February 6, 1997, the former Privacy Commissioner appeared before the Sub-Committee on the Draft Regulations on Firearms of the Standing Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs and indicated that:

- because of a patchwork of privacy legislation in Canada, provisions should be included in the regulations requiring that all personal information be collected and managed in accordance with the federal Privacy Act;

- there are concerns about former spouses and partners being asked to provide their opinions during the screening, which could lead to the collection of inaccurate information and the improper disclosure of personal information about the spouses;

- the only recourse for a review by a judge could result in the unnecessary disclosure to the public of sensitive personal information; and that

- there could be a retention of prohibition orders beyond the intention of the courts.

The Committee accepted only two of the Commissioner's recommendations. First, the Sub-Committee recommended that Memoranda of Understanding be negotiated with each province and territory outlining that the Privacy Act applies in those cases where no provincial law exists and that rules of application be negotiated for the other jurisdictions. The Sub-Committee also recommended that a mediation mechanism outside of the court process be established. Neither of these recommendations were implemented.

The suggestions made during the drafting of the Firearms Act and the Regulations and during the implementation stages to make the Program more privacy sensitive did not result in any substantial changes to the legislation or to the design of the system. The Privacy Commissioner continues to receive numerous inquiries and complaints about the personal information handling practices of the Firearms Program (see nature of complaints at Appendix B). Our privacy concerns relate to:

- the jurisdictional issues with respect to the management and use of sensitive personal information in terms of protection, access, correction, etc.;

- the patchwork of privacy legislation governing the personal information held by federal, provincial and municipal agencies;

- the requirement to negotiate information sharing agreements, and not just service agreements, with all the partners;

- the open and unrestricted use by Firearms Officers of law enforcement databases;

- the information that populates the Firearms Interest Police (FIP) database;

- the intrusive nature of the questions on the licence application forms;

- the broad wording of section 55 of the Firearms Act relating to the "collection of any information reasonably regarded as relevant to determining eligibility";

- the collection of personal information during secondary and tertiary screening investigations;

- the collection of personal information from and about former spouses, and the possible disclosures of their information;

- the appeal process and the need to institute an internal mediation mechanism; and

- the lack of policies and procedures regarding records retention and destruction.

SCOPE OF REVIEW

The purpose of the review was to assess the Canadian Firearms Program's compliance with sections 4 to 12 of the Privacy Act. These sections of the Act relate to the collection, use, disclosure, retention, disposal, and protection of personal information and to an individual's rights of access and correction of this information (see Appendix C).

The review included visits to the Canadian Firearms Centre in Ottawa, the Central Processing Site in Miramichi, NB, the Canadian Firearms Registry at RCMP Headquarters, and to Chief Firearms Offices in Orillia, ON (provincially-administered) and Regina, SK and Edmonton, AB (federally-administered). Our comments and observations in this report are based primarily on the sites visited and, as such, do not apply to the administration of the Program in Newfoundland or Québec, for example.

In February 2001, the Privacy Commissioner decided to re-assess whether the questions about personal history on the firearms licence application form meet the Privacy Act collection requirements. An addendum has been added to this report as Part II of the Findings and Recommendations.

PROGRAM PROFILE

AUTHORITY and MANDATE

The Firearms Act and Regulations apply to any person (including visitors in Canada) and any business that owns, wants to obtain, or uses firearms or that wants to purchase ammunition. The purpose of the legislation is to promote responsible firearm ownership and to keep firearms out of the hands of those who might misuse them. The legislation has a direct impact on the more than 2.3 million firearm owners in Canada. There are over 7 million firearms in Canada. On December 1, 1998, the Act and Regulations came into force along with the new Part III of the Criminal Code with certain exceptions. The Program is expected to be fully operational by the year 2003.

The legislative changes brought about:

- a new screening and licensing system to replace the Firearms Acquisition Certificate (FAC) system, which had been in place since 1979;

- Criminal Code amendments providing mandatory minimum sentences for certain serious crimes where firearms are used;

- enhanced regulations governing the storage of firearms that have been in place since 1993;

- formal controls on the entry and export of firearms into and out of Canada; and

- more controls over illegal movement of firearms.

The Firearms Act has two main requirements:

- A valid firearms licence is required before a firearm can be registered. The law states that, by December 31, 2000, everyone, including minors, visitors, gun dealers, and employees of a business, will need a licence for "possession only" or "possession and acquisition" of a firearm. Licences must be renewed every five years.

- All firearms must be registered. By December 31, 2002, a Registration Certificate with a Firearm Identification Number will be mandatory for every firearm. When an individual receives a gun or transfers one to another person (as a result of a sale, barter or gift), the ownership must be transferred to the new owner. Registration Certificates are valid for as long as the individual owns the firearm, unless it has been modified and the class has changed. There are three classes of firearms: Non-restricted firearms are mostly rifles and shotguns; Restricted firearms are primarily handguns; and Prohibited firearms are automatic and converted firearms as well as handguns with certain barrel lengths. Until they expire (the last one in 2003), the old Firearms Acquisition Certificates are valid.

The Firearms Act requires extensive background checks on every applicant before a licence is issued and before a firearm is sold. Eligibility screening involves two key components:

- Ensuring that all information required to make a decision has been received; and

- Conducting basic criminal/violence background checks of police and court files as well as character references and spousal notifications. Applicants are checked for certain criminal convictions and incidents of violent behaviour. For the purposes of the Act, violent behaviour is defined as any type of violence-not limited to the use of guns-threatened violence or attempted violence against others or the applicants themselves.

Only the Chief Firearms Officer (CFO) in each province/territory and the delegated Firearms Officers (FOs) have the authority to refuse or revoke licences. The screening process can have as many as three stages, if required:

- Primary screening of applicants, based on the information provided on the application form, is done by staff members at the Central Processing Site (CPS) in Miramichi, NB and at the Québec Processing Site (QPS) in Montréal. After it has been determined that the application is complete and the data has been entered into the Canadian Firearms Registration System (CFRS), batch Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) background checks including FIP are conducted electronically with the assistance of the RCMP Accreditation Unit. At the QPS, the Sûreté du Québec assumes this duty. FOs at the CPS can approve totally "clean" applications - that is, information requirements have been met and there are no hits on CPIC or FIP. (Note: Our review did not cover the specific processing activities at the QPS.)

- Secondary screening, if required, which involves a closer look at regional automated police information retrieval databases and telephone follow-up with spouses (desk work) is done by CFOs and their delegates (FOs and support staff).

- Tertiary screening, if required, conducted by Area and Local Firearms Officers is a more in-depth field investigation that can involve interviews with employers, aboriginal leaders, neighbours, etc.

Licensees are checked for eligibility on an ongoing basis in different ways:

- As soon as a new violent incident is logged in FIP, the system automatically searches existing licence holders in the CFRS for a match and alerts the CFO of this development. This could result in a licence being revoked. (Note: Databases discussed below.)

- Court records of relevance to section 5 of the Firearms Act (i.e. prohibition orders) are manually fed into CFRS on a daily basis by CFO staff. This information is not only used to flag existing licence holders, but it also serves as another primary eligibility check on new applicants coming into the system.

- Also, the CFRS maintains other key information used in the ongoing eligibility screening process such as firearms events and spousal notification tables.

During the course of our review, we referred to the Canadian Firearms Centre's web site for a Summary of Key Statistics on the Firearms licensing and registration program (see Appendix D). For Highlights of the Act and its Regulations, refer to Appendix E.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF PRINCIPAL PARTNERS

The administration of the Program is shared by a large number of partners within the public and private sectors. In addition to different government departments and law enforcement agencies at the federal, provincial and municipal levels, there are private sector organizations that have been contracted to administer certain components of the Program. Nonetheless, the Minister of Justice recently reiterated in the House of Commons that "the Government, and in particular the Minister of Justice, will remain fully accountable and responsible for this Program". Although the Canadian Firearms Centre within the federal Department of Justice is expected to provide a single point of accountability, this is difficult since the key federal partners and those provinces that have opted-in play an almost autonomous role in the administration of the Firearms Act. The multi-jurisdictional division of duties has significant implications for the protection of personal information given that the personal information gathered and used to administer the Firearms Act is housed in separate locations across Canada.

Department of Justice Canada (DOJ)

DOJ has responsibility for the overall management of the national Firearms Program. DOJ funds it entirely, including the salaries and equipment costs of provincial and municipal officers involved in the administration of the Program.

The Canadian Firearms Centre (CFC), within DOJ, was created to coordinate the overall implementation of the Firearms Act, including the development of regulations, systems and infrastructure needed to implement the new firearms licensing and registration system. The CFC, which is located in the National Capital Region, is responsible for the overall co-ordination, management and policy development of the Program. The CFC is also responsible for delivering public information relating to the Act, ministerial correspondence, and responding to inquiries.

DOJ manages the main data input facility, the Central Processing Site (CPS) in Miramichi, NB. The CPS handles data input for all licensing and registration applications in Canada, except for those originating in the province of Québec which are handled by the Québec Processing Site (QPS) in Montréal. In addition to processing applications and providing administrative support, the CPS operates a 1-800 call centre to provide public information. At the time of our review, approximately 300 personnel were employed at the CPS, 280 of who were Human Resources Development Canada employees under contract to DOJ. In May 2001 all term HRDC staff working for the Firearms Program were offered deployments to DOJ and indeterminate HRDC staff were offered one-year secondments.

There are 6 opt-in provinces that administer the Firearms Program themselves and 7 opt-out provinces and territories where the Federal Government administers the Program. The opt-in provinces are British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. At the time of our review, DOJ directly ran the Program in Newfoundland and the Yukon, while the RCMP ran the remaining opt-out jurisdictions in the Northwest Region under contract for DOJ (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut).

In March 2001 the management of the Firearms Program in the Northwest Region was transferred from the RCMP to DOJ. All civilian employees were offered deployments from the RCMP to DOJ and RCMP members were offered secondments. Six provinces and territories (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, the Yukon, Nunavut and the Northwest Territories) were combined to form the Northwest Region headed by the Federal Chief Firearms Officer (FCFO). The entire Northwest Region is now managed and administered by DOJ. As well, the CFO site in Newfoundland continues to be administered by DOJ.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

At the time of our review, the RCMP had two main responsibilities:

- Maintain the Canadian Firearms Registry (CFR). Prior to the passage of the Firearms Act, the Commissioner of the RCMP had responsibility for the maintenance of a registry of restricted firearms only-approximately 1.2 million entries. The CFR is responsible for several tasks including the secondary analysis of firearm registration applications, performing CPIC queries on all licence applications, and operating a verifiers network. Approximately 3,500 volunteer verifiers across Canada ensure the accuracy of the description of the firearm by physically examining the firearm and comparing it to the Firearms Reference Table (FRT). Verifiers also assist the clients to properly identify their firearms and complete the prescribed application forms.

- Perform the CFO role in 5 of the 7 provinces and territories that "opted out" of the Program (specifically Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut). However, as noted above, since March 2001, the entire Northwest Region including the Yukon is now managed and administered by DOJ. The DOJ Federal Chief Firearms Officer Services is based in Edmonton.

Chief Firearms Officers (CFOs)

All of the 10 provinces and 3 territories have CFOs who are responsible for administering the Program within their respective jurisdictions. Some CFOs are federal officials while others are provincial officials depending on whether the province has opted-in or opted-out. The provincially-administered CFOs are under either the Attorney General or Solicitor General provincial ministries, while the federal CFOs are employees of DOJ or the RCMP - some of who have recently been deployed or seconded to DOJ.

Firearms Officers (FOs) are appointed by each CFO. FOs' responsibilities include licence application investigations, approval of transfers, spousal interviews, business and residence inspections, licence approval/revocation, participation in court appeals (re: licence refusals), training of Area and Local FOs, supervising amnesty programs as delegated by the CFO, and public presentations.

Depending on the population and the volume of licensing and registration activity, the number of FOs can vary greatly from one province/territory to another. FOs come from varied backgrounds. In some cases, like provincially-administered Ontario, field investigators wear "two hats"-municipal police officers and Area or Local FOs. In other areas, like federally-administered Alberta, none of the FOs are active police officers. Although many of them are former police officers, others come from other professions such as teaching. The Canadian Firearms Centre has developed an investigation training program for all FOs.

Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA)

Since January 1, 2001, the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA) is involved in the customs declarations component of the Firearms Act. Firearm owners and users visiting Canada have to declare all firearms that they wish to bring into Canada. Firearms Declarations must be made in writing and include basic information about the visitors, their destination in Canada, the reason for bringing the firearm into Canada, as well as descriptive information about each firearm. Background checks, including criminal history search, are conducted. Once approved by Customs Officers, Firearms Declarations act as temporary licences and registrations with prescribed expiry dates. Restricted firearms (i.e. handguns) also require an Authorization to Transport.

At the time of our review, this part of the Act was not yet in force. As such, our review did not cover CCRA's personal information handling practices of this new activity related to the movement of firearms. It is also noted that the effective date for imports and exports of firearms will be 2003.

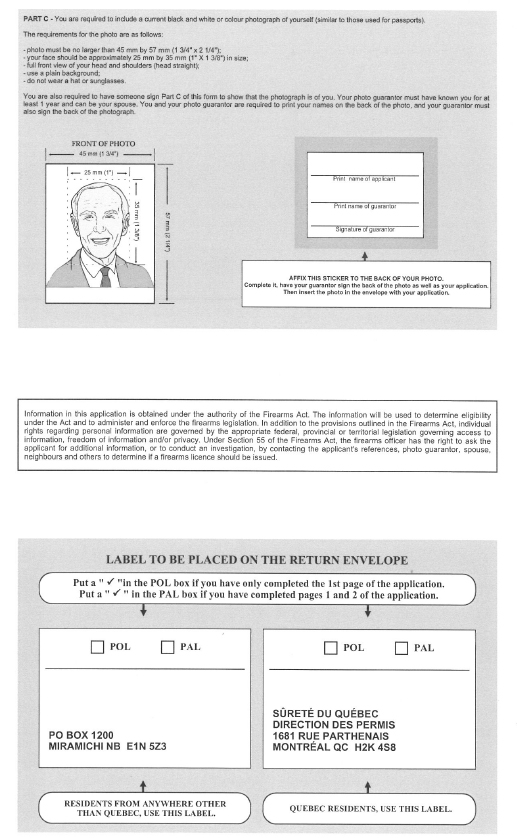

PERSONAL INFORMATION HOLDINGS

The Canadian Firearms Program involves the collection and use of large amounts of personal information. This information includes the applicant's name, date of birth, place of birth, address, gender, eye colour, height, telephone number, and classes of firearms currently owned. For identification purposes, applicants have to provide a photograph, signed by a guarantor, as well as list an official piece of identification (i.e., passport, driver's licence, birth certificate). Applicants also have to answer a series of personal history questions about criminal charges or convictions, suicide attempts, diagnosis or treatment of depression or emotional problems, substance abuse, divorce or separation, bankruptcy, the loss of a job, and whether or not he or she has been reported to the police or social services for violence, threatened violence or conflict in the home or elsewhere. Individuals applying for acquisition privileges are required to provide the name and date of birth of a spouse or common-law partner and the name, date of birth and address of previous (within the last two years) spouses or common-law partners.

All of this information is collected through the application process and all applicants are checked for criminal activity and previously rejected applications. As part of the secondary and tertiary screening, information can be collected from other police databases, current and former spouses or common-law partners, medical practitioners, neighbours, and other community members.

The Program's automated personal information holdings are primarily held in the widely shared Canadian Firearms Registration System (CFRS) with links to the Firearms Interest Police (FIP) database. The CFRS and FIP were created jointly by Justice and the RCMP, solely for the purposes of administering the Program, but the RCMP continues to manage the operation of both information systems. (Note: Databases discussed below.)

While all original application forms are maintained by the Central Processing Site and the Québec Processing Site, the personal information provided on the forms is also captured in the CFRS. The primary screening process is entirely automated, the results of which is recorded in the CFRS. In the event that a licence application requires additional investigation due to a CPIC hit, for example, only the results of the investigation (approved or refused) with limited comments are entered in CFRS. The details about the secondary or tertiary screening investigation (such as police investigation reports and interview reports with spouses, neighbours or community leaders) are maintained by the provincial and territorial CFOs and/or their respective Area and Local FOs.

Canadian Firearms Registration System (CFRS)

The CFRS is a fully integrated, automated information system that is used to enter, analyze, maintain and store all firearms-related information required under the Firearms Act. The CFRS provides administrative and enforcement support to all partners involved in the licensing of firearm owners/users, registration of all firearms, and the issuance of authorizations related to restricted firearms. This network links three areas of responsibility-the Central Processing Site (Justice), the provincial and territorial CFO offices, and the Canadian Firearms Registry (RCMP) by means of a secure national computer network. Data may be entered in one location, electronically processed in another, and access is obtained as required across the entire country.

Depending on the province, the CFRS can be shared among as many as the three levels of government (federal, provincial and municipal). The CFRS is not accessible to the private sector (i.e., gun dealers). The CFRS users include:

- the CPS in Miramichi and the QPS in Montreal for data capture, application processing, exception handling, financial administration, call centre, and records management purposes;

- the 13 CFOs (10 provinces and 3 territories) and their respective FOs for issuing licences and authorizations to carry and transport;

- the Registrar (RCMP) for firearms registrations and import/export authorizations, accreditation and verification; and

- police agencies across Canada for eligibility screening (tertiary field investigations), enforcement support, and recording of found, stolen, lost firearms.

Canadian Firearms Registry On-line (CFRO)

The CFRO (a subset of the CFRS) is a component of the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) designed to provide Canadian police forces with online information about registered firearms in a home or place of business. Police officers can obtain access to registry information from their vehicles or from a communications centre via CPIC. The information is read only and may be queried using name, address, telephone number, as well as the firearm's serial number, authorization number, certificate number, owner number, firearms identification number and licence number. The CFRO system receives an average of 1,800 queries per day.

On a daily basis, information that has been added to CFRS or changed within CFRS is transferred to CFRO. CFRO does not contain all of the information submitted on an application form. If a police officer requires information beyond what is in CFRO for investigation and

subsequent evidence, he or she must contact the Chief Firearms Officer about licence information and the Registrar about firearm and registration information.

Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC)

CPIC is a national automated law enforcement system used for the exchange of information among all 900 plus Canadian law enforcement agencies as well as federal and provincial government departments. CPIC is also linked to the international law enforcement community (the Federal Bureau of Investigation, INTERPOL). CPIC resides within the RCMP's National Police Services Network. While CPIC now contains approximately 3 million files generating over 79 million inquiries annually, not all of them are firearms-related files. Records are entered on CPIC directly by police agencies. The data integrity is controlled by the police agencies and files are audited by approved audit authorities.

The categories of information within CPIC that are routinely queried in the administration of the Firearms Program include Criminal Records/Criminal Name Index, Persons (i.e., prohibitions), Property (i.e., lost or stolen guns), Motor Vehicle Registration and Licence, Firearms Interest Police (FIP), and the Restricted Weapons Registration System (RWRS).

It should also be noted that in the province of Québec, access to CPIC is made by way of a system known as Centre de renseignements policiers du Québec (CRPQ). Our review did not cover the province of Québec.

Police Information Retrieval System (PIRS)

PIRS is the RCMP's automated information management system used to store, update and retrieve information on operational case records/occurrences being, or having been, investigated. This electronic indexing system is used by the RCMP operational units, some municipal police agencies, by Firearms Officers (FO) across Canada, and by other federal partners. PIRS captures data on individuals who have been involved in investigations under the Criminal Code, federal and provincial statutes, municipal by-laws and territorial ordinances. According to the RCMP, in addition to details of an event in a brief synopsis (maximum of 240 characters), PIRS contains limited information relating to investigations and criminal histories. Unlike CPIC, which essentially contains factual information (e.g., charges and convictions), PIRS may also contain information provided by witnesses, victims and other associated subjects that can be highly subjective, as well as the names of the witnesses, victims, and acquaintances of the accused individual. PIRS also differs from CPIC in that it contains information on occurrences and incidents that never resulted in charges.

Operational Statistical Reporting System (OSR) codes identify all occurrences on PIRS in terms of the nature of the event for statistical profile purposes, while the police case number and originating agency (ORI) number are identified in FIP entries for use by FOs.

Provincial and Municipal Police Information Retrieval Systems

Similar to the RCMP's PIRS database, Ontario has a police information retrieval system known as OMPACC, while Calgary has PIMS, Edmonton has PROBE, Regina has IRIS, etc. Formal and informal information sharing arrangements are in place between provincial and territorial CFOs and their police services boards or agencies for the exchange of information in these databases.

Firearms Interest Police (FIP)

The FIP database was created in 1998 to meet the objective of section 5 of the Firearms Act by flagging those individuals who may be ineligible to hold a licence (see 3rd page of Appendix E). The RCMP is the custodian of the FIP database, while the policy and management centre for FIP (collection, quality control, operation, cost and effectiveness) resides with the Canadian Firearms Centre under DOJ. The Chief Firearms Officers across Canada have selected a list of police incident reporting codes that are used to populate the FIP database to satisfy the provisions of section 5 of the Firearms Act. There are over 900 law enforcement agencies across Canada that feed information for flags in FIP via the National Police Services Network. In addition, flags in FIP are sometimes entered by Program officials (e.g. spousal concerns entered by CFOs, FOs, AFOs, etc.). As of December 1999, there were 3,528,751 FIP records.

The FIP system was designed to alert CFOs and FOs, when screening applications for firearms licences, about individuals who have been involved in incidents of domestic violence, threats of violence, harassment, etc.; individuals with warrants for arrest; and individuals who have been refused licences and authorizations or who have attempted to bring firearms into or out of Canada without proper authorization. Any act of violence or threat of violence related to criminal activity, mental illness, or a history of violent behaviour, for example, can be entered into FIP even though it may not have resulted in criminal charges. A FIP entry does not result in an automatic refusal to issue a licence.

The amount of information produced as a result of a FIP hit is minimal. A FIP entry consists of name, date of birth, CPIC Originating Agency (ORI) number and the agency incident number. Police agencies across Canada record activities on FIP using established Universal Crime Reporting (UCR) codes and the RCMP uses the PIRS Operational Statistical Reporting System (OSR) codes. No information is revealed on FIP about the role of the individual or the type of incident. This is deliberate to reduce the potential for the misinterpretation and misuse of the data, since the person making the query has to contact the contributor to discover the facts of the case. FIP is intended to act strictly as a pointer, referring CFOs and FOs to other databases such as PIRS and similar provincial and municipal police databases or to the agency that entered the incident.

Most of the police contributions to FIP are done through the use of locally based, automated programs that extract tombstone data from agency incident systems and forward it to CPIC. However, police can also make a FIP entry manually, using a CPIC terminal, if the agency does not have an automated extract program. The CPIC system retains the entry in the FIP category for five years, after which it is automatically deleted unless the agency deletes the entry prior to the five years. For FIP to be effective in providing early warning signals of potential violence, it is vital that police officers keep their incident reports accurate and up-to-date regarding the status of persons responsible for the incidents covered by section 5 of the Firearms Act.

On a daily basis, the new FIP entries in CPIC are compared to information on persons listed in the firearms licence files in the CFRS, including applicants. If there is no match, then nothing happens. If a person in a FIP entry in CPIC later applies for a firearms licence, the FIP entry will be found during the initial licence screening process. If there is a match, CFRS will send a message to the Chief Firearms Officer of the province or territory in which the incident concerning the licence or applicant took place, indicating there is now a police file that may affect continued eligibility for a firearms licence. Again, this message includes only the name and age or date of birth of the person, as well as the case file number and CPIC ORI number.

A Firearms Officer then conducts what is known as a secondary investigation to ensure the match is valid. If the match is invalid, the event is removed from CFRS. If a positive match is found, the Firearms Officer will further investigate with the police agency involved to obtain more detailed information. This tertiary investigation will result in a recommendation as to whether or not a person should be issued a licence, or whether or not their licence should be revoked.

Though it is the responsibility of each CFO to ensure that all FIP hits against a CFRS client are thoroughly reviewed, FIP records are created by police agencies and data integrity is therefore controlled by the police agencies. This means that the reliability of the FIP database depends on the police agencies entering the data. Proper recording of public safety incidents should ensure that the FIP database is accurate and up-to-date. The RCMP accepts responsibility for only those records entered on FIP by RCMP detachments.

Hardcopy Records

At the time of our review, DOJ maintained hardcopy personal information at:

- the Central Processing Site (CPS) in Miramichi, NB (mostly applications and primary screening records);

- the Canadian Firearms Centre in the National Capital Region (inquiries and ministerial correspondence from clients); and at

- the federally-administered CFO site in Newfoundland and in the Yukon Territory (secondary and tertiary screening records as well as information about safety course results).

While the RCMP maintained hardcopy personal information at:

- the Canadian Firearms Registry (CFR) in RCMP Headquarters (verification and accreditation files, registration certificates, and correspondence of CFRS clients, as well as tombstone identifying information about the 3,500 volunteer verifiers); and

- within the Federal Chief Firearms Officer Services and at each of the CFO sites of the five opt-out Northwest Region jurisdictions - Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Northwest Territories and Nunavut (secondary and tertiary screening records as well as information about safety course results).

With the transfer of responsibilities from the RCMP to DOJ in March 2001, the personal information maintained by the CFOs in all seven "opt-out" provinces and territories (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, the Yukon, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Newfoundland) is now maintained by DOJ.

The remaining CFO sites for the "opt-in" provinces (British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island) maintain all hardcopy program records with the exception of the initial applications and primary screening records that are held at the CPS/QPS. In these opt-in jurisdictions, the CFOs maintain the secondary screening records and safety course results while the tertiary screening files (field investigations) are primarily maintained by the municipal police agencies.

Also, at the time of our review, the Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA) did not yet hold any personal information about the Firearms Program clients since the effective date for custom declarations was January 1, 2001 and the effective date for imports/exports will be 2003.

FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS - PART I

For a List of all Recommendations, refer to Appendix A.

ACCESS & CORRECTION

One of the purposes of the federal Privacy Act is to give individuals a "right of access" to information about themselves held by a government institution. This includes, but is not limited to, a right to request correction of the information. Such a right is considered to be a fundamental element of fair information practices. This right is found in most personal information protection acts, including the new Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

Under section 7(5) of the Firearms Records Regulations, an individual who wants personal information amended shall submit an application in writing to the Registrar or to the CFO in the province or territory in which the record was created. The Firearms Act and the Regulations do not provide individuals an explicit right of access to their information unless it is for the purpose of correcting their information.

In April 1997, a Parliamentary Sub-committee recommended that mediation mechanisms be established, on an administrative basis, to allow applicants the opportunity to challenge allegedly false or inaccurate information without resort to court action. The Government did not accept this recommendation because, in its view, investigative techniques already exist to ensure that decisions are not based on false or inaccurate information. While DOJ agreed to examine the investigative process to see if improvements should be made with a particular focus on privacy, the Government believed that mediation after the fact would not be appropriate and could be incompatible with the overriding safety objectives of the legislation.

The Canadian Firearms Centre Web site (www.cfc-ccaf.gc.ca/general_public/factsheets/privee_en.) states that "Any personal information collected under the new firearms legislation is protected by the basic principles of fair information practices found in the federal Privacy Act and in provincial privacy legislation." Despite this claim, all Canadians cannot easily obtain access to information collected as part of the Firearms Program particularly given the multi-jurisdictional nature of the Program.

In the case of the seven opt-out jurisdictions (AB, SK, MAN, NWT, Nunavut, Yukon and NFLD), all records are administered federally, and thus subject to the Privacy Act. However, the Program records relating to the six opt-in jurisdictions (BC, ON, QC, NB, NS, PEI) are held by three levels of government (federal, provincial and municipal), and thus subject to a patchwork of privacy legislation. Even at the federal level the personal information holdings for this Program are held at various locations.

The dispersed holdings result in an uneven application of access rights. In March 1999, the Federal Chief Firearms Officer Services (FCFO) for the 5 opt-out jurisdictions in the Northwest Region issued its own Access and Privacy Requirements Bulletin and prepared a draft Personal Information Policy Statement. Though the FCFO should be commended for this initiative, no consultation took place with the RCMP/Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) office or with DOJ/ATIP. As a result, ATIP officials from the RCMP and DOJ are not in agreement with some of the policies and procedures outlined in the FCFO Bulletin in terms of what is and what is not considered personal information that a client would be entitled to receive and whether formal or informal requests should be submitted to CFOs or directly to the federal ATIP offices.

At this time, each partner, in responding to access requests, is processing the records in its custody and referring applicants to the other likely holdings (federal, provincial and/or municipal). For example, DOJ/ATIP is only processing CPS and CFC records (including CFRS extracts relating only to licences), and referring requests relating to the registration of firearms to RCMP/ATIP.

In addition, several problems exist with respect to requests for access and correction to records held in FIP. Any requests involving the FIP database are automatically referred to the RCMP for response. However, in turn, the RCMP is only processing FIP records that have been entered by the RCMP. When a request for a FIP printout is received at RCMP/ATIP and the information was entered by another police force, the RCMP exempts all the information referring to that entry as received in confidence because the RCMP does not know the circumstances for the entry, the sensitivity of the information, or other relevant details of the entry. The individual is then referred to the local police agency where a separate additional access request must be made. This results in delays due to individuals being referred from one office to another, and there are no established procedures to cancel, correct or remove unsubstantiated/innocuous FIP hits or those that fall outside of the requirements of section 5 of the Firearms Act.

Also, for example, an Ontario resident who applies for a firearms licence and registration certificate and who has been subject to the three levels of screening (primary, secondary and tertiary) would have to submit separate access requests to DOJ (Central Processing Site and Canadian Firearms Centre), the RCMP (Canadian Firearms Registry and FIP), the Ontario Provincial Police as well as to at least one local police agency. A fifth request may also be required if the CFO or Area and Local FO in Ontario also obtained additional information from a police agency outside the province. This is a tremendous burden on individuals who simply want access to their records collected under the Firearms Act.

Since not all provinces, territories and municipalities come under privacy legislation comparable to the federal Privacy Act, this results in uneven protection of individuals' privacy and rights of access and correction with respect to the Firearms Program records. For example, Prince Edward Island does not yet have any privacy law in place and only a handful of provinces in Canada have extended their privacy legislation to their municipalities (see Appendix F).

The variations in the existing Memoranda of Understanding among the partners and levels of government have led to inconsistencies with respect to the control and ownership of the personal information - thus resulting in different access and correction procedures (see Appendix G).

Personal Information Request Protocol

In April 1997 following Parliamentary Committee recommendation, the Minister of Justice undertook to negotiate information sharing agreements that would ensure that the federal Privacy Act would apply in cases where no provincial and territorial legislation exists. However, there are still no such agreements in place. As a temporary measure, DOJ issued in October 1999 a Personal Information Request Protocol to all provincial and territorial CFOs. The Protocol sets out DOJ's position with respect to ownership and control of Program records and how access requests "should" be processed.

According to DOJ's Protocol:

- though the CFRS is staffed and operated by federal employees, "ownership" of its contents is not possible since the information contained in the CFRS can be entered, modified and retrieved by all federal, provincial and territorial partners;

- a document is under the "control" of a government institution if it is within that institution's power to produce it; the ability to produce a record would encompass not only those records which that institution has custody of or is in direct possession of, but would also include records that are generally available to that institution including any record which that institution may access or retrieve by way of agreement;

- the nature of information sharing and gathering in the CFRS and the provisions of the Firearms Act giving reciprocal rights of access to the CFOs and the federally-appointed Registrar, give every partner the ability to produce the information; therefore everyone potentially has control of the information and is subject to personal information requests;

- all records received by the Central Processing Site (CPS) are stored on behalf of DOJ; the CPS is operated by federal employees and therefore all information within its control is subject to the federal Privacy Act; this includes original applications, primary screening as well as results and limited remarks of secondary and tertiary screening entered in CFRS;

- any other investigative records gathered during secondary and tertiary screening are not under federal control and thus not subject to federal privacy legislation;

- personal information requests received by DOJ are processed in accordance with the Treasury Board Guidelines on Privacy and Data Protection; DOJ consults with all parties concerned before a decision is made to release a record; for example, consultations are held whenever a request is received for information that has been entered into the CFRS by a provincial and territorial partner;

- DOJ informs a requester that the provincial or territorial institution may have information relevant to their request; and

- in cases where a request is received by the province/territory and there are relevant records stored at CPS, the provincial and territorial CFO will request those records directly from the federal CPS site.

Although the Protocol begins to capture the complexity of the ownership and control issues as well as the access problems, it fails to acknowledge the key issues with respect to the personal information holdings, sharing arrangements and actual practices. Among other things, the Protocol needs to:

- recognize the information holdings at the RCMP Canadian Firearms Registry (CFR);

- differentiate between the 7 opt-out jurisdictions (federally-administered) that do fall within the federal Privacy Act and the 6 opt-in jurisdictions (provincially-administered) that do not, especially regarding secondary and tertiary screening records;

- address how individuals residing in PEI can obtain access to their information given that there is no comparable privacy legislation for that "opt-in" province;

- provide guidance to provincial and territorial CFOs as to whether or not tertiary field investigation files held by municipal police agencies should be gathered in response to access requests; and

- it should address all the access and correction issues associated with the FIP records.

The Protocol also raises an interesting point. While the provincial and territorial CFOs can pull records from the federal CPS site for processing access requests received at that level of government, DOJ cannot pull provincial and territorial records to process requests received at the federal level.

Recommendations:

- All the existing Memoranda of Understanding (a.k.a Service Agreements) should be reviewed in order to standardize the control and ownership clauses.

- DOJ should follow through on its promise to negotiate information sharing agreements with the provinces and territories. These agreements should apply to both electronic and hardcopy records and should also apply to the Firearms Interest Police (FIP) database as well as all federal, provincial and municipal police information retrieval systems. This would ensure that the personal information collected for the Firearms Program is protected in accordance with the intent and spirit of the federal Privacy Act and the principles of fair information practices, and that the Act applies in cases where no parallel provincial and territorial privacy legislation exists. In the event of a conflict between the federal Privacy Act and the provincial privacy acts (e.g. no correction rights at the provincial level), the agreements could expressly state that the federal Privacy Act would prevail.

- In the interim, until DOJ puts in place appropriate information sharing agreements, the DOJ Protocol should be revised to:

- recognize the information holdings at the RCMP Canadian Firearms Registry (CFR);

- differentiate between the 7 opt-out jurisdictions (federally-administered) that do fall within the federal Privacy Act and the 6 opt-in jurisdictions (provincially-administered) that do not, especially regarding secondary and tertiary screening records;

- address how individuals residing in PEI can obtain access to their information given that there is no comparable privacy legislation for that "opt-in" province;

- provide guidance to provincial and territorial CFOs as to whether or not tertiary field investigation files held by municipal police agencies should be gathered in response to access requests; and

- it should address all the access and correction issues associated with the FIP records.

- Mechanisms should be in place to ensure that individuals have easy access to FIP records and the ability to correct or place a notation to file relating to disputed FIP entries.

- Consideration should be given to creating a single access and correction point at the federal level. Given that the Program is administered through a federal statute, the provinces are fully funded by the Government of Canada, and that overall accountability for the Program rests with DOJ, individuals should not have to go to as many as 4 to 5 different places to obtain access to their personal information. This should be negotiated as part of the information sharing agreements.

Personal Information Banks in InfoSource

InfoSource is a publication issued by the Treasury Board Secretariat for the purpose of assisting Canadians in identifying and locating their personal information holdings within federal government departments and agencies.

During the course of our review, DOJ provided a draft description of a new personal information bank (PIB) entitled "Firearms Program Records", which was to be issued in InfoSource. It stated:

"This bank contains applications and other information related to: the ownership, registration and use of firearms; the importation, exportation and other movement of firearms; the licensing of businesses and other entities; and the licensing of individuals under the Firearms Act and related Regulations. ...Information is this bank may be maintained in hard copy, on microfilm, and in automated form in the Canadian Firearms Registration System."

This description in this PIB did not begin to capture the extent to which sensitive personal information is being collected (i.e. medical and criminal records). Also, it did not reflect the role of the RCMP and other partners, which could prove quite confusing not only to applicants but to the ATIP community as well.

In September 1999, the RCMP notified the Privacy Commissioner under section 9(4) of the Privacy Act of its intention to update bank CMP PPU 005 - Operational Case Records - to recognize that FOs have access to the RCMP's automated Operational Case Records by way of the Police Information Retrieval System (PIRS). This proposed new "consistent use" is addressed later in this report as there are collection issues with respect to giving FOs full and open access to PIRS data.

In the 1999/2000 version of Info Source, the RCMP listed personal information bank CMP PPU 035 - Firearms Registration/Legislation Records, which covered only its previous responsibilities under the Criminal Code including maintaining the Restricted Weapon Registration System (RWRS) and the old Firearms Acquisition Certificates (FAC). There was no mention of the RCMP's new responsibilities and personal information holdings as a result of the Firearms Act (i.e. CFR, FIP, Verifiers' Network, etc.).

But then, subsequent to our Preliminary Report in September 2000, both DOJ and the RCMP issued new personal information banks in the 2000/2001 publication of InfoSource - JUS PPU 199 Canadian Firearms Program and CMP PPU 037 Canadian Firearms Registration System, respectively. While both departments should be commended for preparing such detailed bank descriptions, some problems remain. For example:

- While DOJ's new PIB indicates that requests related to the Firearms Interest Police database (FIP) should be directed to the RCMP, the RCMP has not created a PIB for FIP (contrary to previous undertakings) nor is there a mention of FIP in its new CFRS bank.

- There is no mention by either DOJ or the RCMP about the personal information gathered relating to the qualifications of verifiers.

- In DOJ's new PIB, it states that "Details of interviews and reports are held by the provinces and territories." But, this is not always the case since DOJ administers the Program for opt-out provinces and territories and maintains the records at the federal level. Only later in the PIB does it talk about the opt-in and opt-out differences. This can be quite confusing as it creates uncertainty as to whether they should apply federally, provincially or municipally, or to all three jurisdictions in order to obtain access to their personal information.

- In DOJ's new PIB, it also states that "For PEI and the opt-out provinces...requests must be made to Justice Canada". But, immediately after it states that information collected by municipal or provincial police forces is not under the control of DOJ. Again, this is contradictory and could prove quite confusing to the average citizen. In addition, it remains unclear as to why all the records held in PEI would be under DOJ's control since this is an opt-in province. Also, this contradicts DOJ's other statements that residents in PEI can obtain access to their personal information at the provincial level.

- In DOJ's new PIB, it also states that requests relating to training records should be sent to Justice. It remains unclear if DOJ has control over all training records - opt-in and opt-out jurisdictions.

- Finally, it remains undetermined what personal information is being collected by CCRA since January 1, 2001.

Recommendations:

- Before DOJ and the RCMP can finalize their personal information bank descriptions for Info Source, they need to resolve a number of issues associated with access and correction rights such as control of both hardcopy and automated records held in the various jurisdictions.

- Any bank(s) in InfoSource should differentiate between DOJ holdings (i.e. CPS, CFC, CFOs in opt-out provinces and territories), those of the RCMP (i.e. CFR and Verifiers' Network), as well as those of the "opt-in" provinces.

- Any bank(s) for the Firearms Program should describe CFRS and CFRO as well as the types of information collected for eligibility screening (i.e. criminal, medical, etc.) including the various sources such as references, guarantors, doctors, spouses, employers, CPIC, FIP, PIRS, etc.

- The RCMP's Operational Case Records bank (CMP PPU 005) should specify to what extent FOs have access to the records via PIRS - an issue addressed as part of this review.

- The Firearms Interest Police (FIP) database must be reflected in InfoSource.

- The personal information relating to the qualifications of verifiers should also be recognized in InfoSource.

- DOJ's bank description should clarify who has control over all training records - for both the opt-in and opt-out jurisdictions.

- The new PIBs should also establish what personal information is being collected by CCRA since January 1, 2001, and refer to another PIB if necessary.

COLLECTION

In addition to the large amount of personal information collected on application forms (see Findings and Recommendations - Part II of this report), the Firearms Act gives FOs very broad powers and discretion to investigate and gather additional information about applicants. Under section 55 of the Firearms Act, FOs have the right to ask applicants for additional information, or to conduct an investigation by contacting the applicants' references, photo guarantor, spouse, neighbours, aboriginal elders or leaders and others to determine if a licence should be issued. This next part of the review focuses primarily on the collection of information during secondary and tertiary screening.

Police Information Retrieval System (PIRS)

PIRS is the RCMP's automated information management system that captures data on individuals who have been involved in investigations under the Criminal Code, federal and provincial statutes, municipal by-laws and territorial ordinances. In addition to details of an event in a brief synopsis (maximum of 240 characters), PIRS contains limited information relating to investigations and criminal histories. Unlike CPIC, which essentially contains factual information (e.g., charges and convictions), PIRS may also contain information provided by witnesses, victims and other associated subjects that can be highly subjective, as well as the names of the witnesses, victims, and acquaintances of the accused individual. PIRS also differs from CPIC in that it contains information on occurrences and incidents that never resulted in charges. Operational Statistical Reporting System (OSR) codes identify all occurrences on PIRS in terms of the nature of the event for statistical profile purposes, while the police case number and originating agency (ORI) number are identified in FIP entries for use by FOs.

Initially, with the creation of the FIP system, PIRS was intended to be used by CFOs and their staff strictly as a pointer directing them to the originating agency's occurrence report, and only following a FIP hit showing a PIRS file. Then, in 1998, the RCMP informed the CFOs that their staff would be provided with full PIRS query access, but with the following conditions outlined in an MOU:

- the PIRS data base is to be used only by authorized personnel with an enhanced security clearance and who have had appropriate training on the use and limitations of the system;

- under no circumstances are eligibility decisions to be based solely on information retrieved from the PIRS data base; the records in PIRS are by no means exhaustive in nature and it is incumbent on each CFO and his/her staff to confirm the contents of any record with the originator prior to considering any action;

- PIRS queries are to be limited solely to information that is necessary for eligibility processing, investigations and proceedings under the Firearms Act, Criminal Code or court order; and

- subject queries should include appropriate subject information such as surname, given names, sex and date of birth, to limit the search to appropriate responses.

However, it was not until a year later (in September 1999) that the RCMP notified the Privacy Commissioner, as required by section 9(4) of the Privacy Act, of its intention to amend the "Consistent Uses" portion of the Operational Case Records bank in Info Source to reflect that FOs were granted full access privileges to the records by way of PIRS.

Providing FOs with full access to PIRS raises a number of concerns:

- PIRS records have data quality problems. The PIRS Policy Centre, within the RCMP, has expressed a concern that decisions are being based on records that frequently contain inaccurate accounts of investigations, including inaccurate subject status codes. Section 6(2) of the Privacy Act requires that all reasonable steps are taken to ensure that personal information used to make an administrative decision about someone is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible.

- Despite RCMP PIRS Policy, the information found on PIRS is not being verified with the contributing agency most of the time. Due to workload requirements, FOs are only checking the contributing agency file if a licence application requires a more in-depth investigation or if the application will be refused based on PIRS data. If the FO is satisfied that the information obtained on the PIRS terminal is not a match to the client, or that the information falls outside of section 5 of the Firearms Act (not a threat to public safety), the originating police agency's file is not verified.

- PIRS contains information about "associated" subjects that are not CFRS clients (e.g., witnesses, victims, etc.). Thus, FOs are routinely privy to considerable personal information that is normally not relevant to their decision-making process.

- Since the RCMP and all police agencies contributing to PIRS already screen operational case files to identify PIRS entries with relevance to section 5 of the Firearms Act for automatic flags in FIP, FOs should only consult PIRS as a result of a FIP hit and by using Screen 20 along with the police case number and originating agency (ORI) code provided in FIP. However, FOs have full and open access to PIRS. Checks that are not a result of a FIP hit are done using screen 22 instead, which only requires name and date of birth.

While the CFOs in the Northwest Region insist that they cannot function without PIRS, the CFO in Ontario does not have a PIRS terminal nor does that CFO see the need for one. Through an informal arrangement, the Ontario CFO has the Nova Scotia CFO check PIRS an average of six times a week. Even though Ontario has a high volume of licence applications the CFO can function well using this intermediary. In response to our Preliminary Report, in January 2001 Justice officials explained that Ontario has a limited need for PIRS because that province has a parallel system called OMPPAC (Ontario Municipal Provincial Police Automation Contact). However, our review confirmed that other provinces, like some in the Northwest Region, also have parallel police information retrieval systems but still insist on using PIRS as well. We are not convinced that PIRS terminals are needed in all of the jurisdictions.

Within the RCMP community the use of PIRS has been an extremely sensitive issue. Some RCMP officers support the FOs' use of PIRS while other RCMP officers are opposed. The RCMP ATIP and IT groups are adamant that tighter controls need to be in place to limit the use of PIRS by FOs, and that all PIRS data should be verified with the originating agency. Some RCMP officers have even indicated that PIRS terminals should be removed completely from CFO sites to ensure that the RCMP does not lose control over the use of this "police" data.

Recommendations:

- PIRS terminals in CFO and FO offices should only be available for those jurisdictions that do not have parallel police information retrieval systems.

- Access to the PIRS database should be tightened by restricting FOs to limited, specific and relevant information only. FOs should not be granted open and full access to PIRS.

- Since the RCMP and agencies contributing to PIRS already screen Operational Case Files to identify entries relevant to section 5 of the Firearms Act for flags in FIP, FOs should request PIRS checks only following a related FIP hit. As such, all searches on PIRS should be conducted using Screen 20 only and with the case number and originating agency (ORI) code as a search tool.

- FOs should be restricted from using Screen 22 (which allows searches by using only the name and date of birth). This screen is used for more general and wider searches by law enforcement agencies. FOs already have access to CPIC for this purpose.

- Since it is technically possible to restrict access to PIRS to certain screens, FOs should be restricted from having access to information about associated subjects (e.g. witnesses and victims) linked to CFRS clients. In those rare cases where information about associated subjects is required, Firearms Officers should request this information directly and in writing from the RCMP.

- All PIRS information used by a FO to make an administrative decision about an individual who has been positively identified as a CFRS client should be verified with the contributing agency-regardless of whether it is an approval, refusal or revocation process.

- Verification should be made to ensure that the PIRS database is used only by authorized personnel with an enhanced security clearance, followed by a refresher course on the appropriate use and limitations of the system.

- Retention and disposal policies should be instituted to extend retention periods of originating agency files as a result of any activity linked to FIP PIRS data.

- Similar to the well-developed CPIC audit functions, the RCMP should establish and implement an automated PIRS audit function to ensure that complete, up-to-date and accurate information is gathered on PIRS and to ensure the proper use and protection of PIRS data by FOs.

- The existing Memoranda of Understanding with each province and territory specific to the use of PIRS data should be amended accordingly, and related national policies and procedures should be drafted.

Provincial and Municipal Police Information Retrieval Systems

Similar to the use of the RCMP's PIRS database, access by FOs to provincial and municipal police information retrieval systems (i.e., Ontario's OMPPAC, Regina's IRIS, etc.) is intended to ensure that all relevant material is available to assist FOs in making informed decisions about CFRS clients. However, caution should be exercised to ensure that only the information that is needed to administer the Firearms Act is exchanged between local police agencies and FOs.

It was also noted that the MOU between the Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General (OPP/CFO) and the Ontario Police Services Board fails to cover the use of the police information retrieval system in Ontario called OMPPAC.

Recommendations:

- Similar to the recommendations made with respect to PIRS, the same access restrictions should be applied relating to all police information retrieval systems in Canada that are used to make decisions about individuals under the Firearms Act.

- Likewise, any Memoranda of Understanding relating to the provincial and municipal police information retrieval systems should be amended accordingly, and the specific databases used by FOs should be covered in the MOUs.

Firearms Interest Police (FIP)

In order to meet the objective of section 5 of the Firearms Act, the FIP database was created in 1998 with five years of back data from police agencies for the purpose of flagging individuals who might not be eligible to hold a firearms licence. These are individuals who have been involved in incidents of domestic violence, threats of violence, harassment, etc.; individuals with warrants for arrest; and individuals who have been refused licences and authorizations or who have attempted to bring firearms into or out of Canada without proper authorization. Any act of violence or threat of violence related to criminal activity, mental illness, or a history of violent behaviour, for example, can be entered as a flag in FIP even though it may not have resulted in criminal charges (see 3rd page of Appendix E).

The problem with FIP is not the amount of information it holds about individuals-the amount is limited and factual (name, date of birth, incident code and number). However, the data captured during the initial inception of FIP varies because different police agencies had different incident reporting codes for similar police incidents. As a result, in some cases, the database contains entries on individuals who should never have been flagged as they do not meet the ineligibility criteria under section 5 of the Firearms Act. A FIP hit sometimes directs the FO to unsubstantiated and derogatory information, unproven charges or allegations, hearsay, records that are older than 5 years, incidents and charges that have been cleared or acquitted, duplicate entries as well as information about witnesses, victims of crime and various other associated subjects. People are unaware that they are being flagged in FIP as possible risks to public safety. Also, inaccurate information on FIP or information that has already been the subject of a previous investigation and cleared, is used over and over.

In January 2001 in response to our Preliminary Report, DOJ indicated that a new software application has since been implemented to reduce the problems associated with the extraction and upload of incorrect data to FIP. DOJ continues to work towards establishing and implementing common police agency extract standards and procedures. For example, as a result of one of our recommendations, the extract codes were recently modified in an effort to ensure that information on subjects who are simply "associated" with FIP files (e.g. witnesses and victims) will no longer be included in FIP. While the problems have been reduced, they are not eliminated due to the five years of back data that was first used for the upload.

Like any other record maintained on CPIC, the originating agency, or contributor, has the capability of manually adding or deleting a record from the FIP file. The audit requirements of the CPIC policy manual dictate that a record must exist in the police agency database to support the FIP entry on CPIC. Police agencies that create an entry in their local police index and subsequently remove the entry because the suspect was cleared, are also obliged to remove the FIP entry from CPIC. Should an error come to the attention of a FO during the course of an investigation, the FO is supposed to contact the originating agency. It is up to the agency to make a determination if the record is no longer relevant and to make the necessary corrections. The RCMP claims responsibility for only those records entered on FIP by RCMP detachments.

At this time, neither the RCMP nor DOJ has a framework or methodology in place to verify how many of the FIP records fall outside of the requirements of section 5 of the Firearms Act. In addition, outside of the formal channels under the Privacy Act, there is no way of knowing how many times a FIP file has been subject to a correction request (formal or informal). Each contributing agency would have to be canvassed to determine how many police occurrence reports have been subject to correction requests and whether any related FIP entries have actually been corrected. There is no way of knowing if all 900 plus contributing agencies are keeping such records.

Recommendations:

- Since DOJ's Canadian Firearms Centre is responsible for issues respecting data quality on FIP and in conformity with section 6(2) of the Privacy Act (accurate, complete and up-to-date information), there should be an auditing framework to verify the validity and accuracy of FIP records.

- The Canadian Firearms Centre FIP Project Team should continue to work towards establishing and implementing common police agency extract standards and procedures, and a copy of the report(s) of improvements should be provided to the Privacy Commissioner.

Social Insurance Number (SIN)

Initially, the Canadian Firearms Centre applications for possession and acquisition of licences required applicants to list two types of identification. The application forms, which are issued by DOJ, provided the following examples to applicants: "passport, driver's licence, health card, birth certificate, social insurance card, citizenship certificate, landed-immigrant document or other similar document". The Canadian Firearms Program is not listed as an authorized user of the Social Insurance Number in the Treasury Board's 1989 Policy on Data Matching and Control of the Social Insurance Number, nor is the use of the SIN authorized under the Firearms Act or its Regulations.

We are pleased to report that, during the course of our review, the forms were redesigned and the reference to "social insurance card" has been removed.

Collection from Credit Reporting Agencies

The FOs' Investigation Guide, prepared by the Ontario Transition Team, indicates that confirming information in the application can include searching or consulting Credit Bureau files. Though the licence applications ask if an individual has experienced a bankruptcy, we question why FOs need to search Credit Bureau files, how frequently these files are being searched and for what specific purpose.

Recommendations:

- Policies and procedures should be implemented regarding the collection of personal information from credit reporting agencies, and a copy should be provided to the Privacy Commissioner.

Telephone Monitoring at the Central Processing Site (CPS)

Employees' telephone conversations are being monitored randomly at the CPS in Miramichi for quality checks and performance appraisal purposes. A report is usually written and then shared with the employees concerned; however, a recording of the actual conversation is not retained. Currently, only DOJ FOs are provided with a written notice that they must sign. The remaining 280 HRDC employees are simply told of the telephone monitoring when they are hired.