2019-20 Departmental Results Report

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

(Original signed by)

The Honourable David Lametti, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2020

Catalogue No. IP51-7E-PDF

ISSN 2560-9777

Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Departmental Results Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020.

It was a challenging year of defending and advocating for the privacy rights of Canadians that ended as the world faced the COVID-19 pandemic. In this year, we implemented the permanent funding increase of 15% received in the 2019 federal budget. This allowed the OPC to expand its capacity to protect the privacy of Canadians, especially in the face of the exponential growth of the digital economy.

It was a challenging year of defending and advocating for the privacy rights of Canadians that ended as the world faced the COVID-19 pandemic. In this year, we implemented the permanent funding increase of 15% received in the 2019 federal budget. This allowed the OPC to expand its capacity to protect the privacy of Canadians, especially in the face of the exponential growth of the digital economy.

For example, we completed advice for individuals on privacy breach notifications. We also completed an extensive update on our guidance to federal institutions on privacy impact assessments.

We also received temporary funding to help us reduce a very large part of our investigative backlog of complaints older than a year. Our Office was able to reduce the overall backlog of complaints older than 12 months by 50% from last year.

Certainly, these new resources helped us bridge the gap between our capacity and delivering what Canadians need to protect their privacy. However, there is still a very significant gap.

We know from our public opinion polls that the vast majority of Canadians are concerned about the protection of their privacy. We also know that Canadians feel they have little to no control over how their personal information is being used by companies and government. Ultimately, our activities serve to increase the level of trust and protection of Canadian’s privacy rights. Survey results show us that there is still a lot of work to do. For example, while we produced guidance on COVID-19 matters and many other issues, most privacy issues are not subject to up-to-date guidance or any guidance at all.

While the injection of funds helped us to better respond to complex and fast-moving social and technological changes that affect Canadians’ privacy, additional resources do not fully respond to the challenges facing privacy.

We also need to make fundamental changes to our laws to protect the rights of Canadians and restore balance in their relationships with global organizations with unlimited resources. Robust privacy laws are key to promoting trust in both government and business and without that trust, innovation and growth can be severely affected.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the gaps in our legislative framework all the more striking – and the need for modernized laws all the more urgent.

Technology is playing an important role as governments and public health officials try to stop the spread of COVID-19, for example, in the development of contact tracing and exposure notification applications. Meanwhile, the pandemic has also accelerated the use of technology for socializing, working, going to school and seeking medical advice.

All of this is happening in a context where our current privacy laws do not provide an effective level of protection suited to the digital environment.

We are facing uncertain and extraordinary circumstances during the pandemic. They reveal just how important it is to have a rights based approach to law reform. Entrenching privacy in its proper human rights context remains not just relevant, but more necessary than ever.

The pandemic has also had an impact on OPC operations – as it did across the federal government and the private sector.

The OPC responded quickly and effectively to the challenge by shifting almost all staff to telework as they maintained operations. We continued to investigate violations of the laws and kept our IT system running smoothly so as to continue to offer our services to Canadians. We continued to review breaches, answer questions from the public and the media and prepare for parliamentary appearances.

We also rose to the challenge of addressing privacy issues raised by the public health crisis. In the final weeks of the fiscal year, our Office developed and released guidance showing how privacy can still be protected while facing the pandemic. We also began work on a contextual framework to help business and government assess the privacy impacts of their responses to COVID-19.

In the early weeks of the next fiscal year, the OPC built on the groundwork done in 2019-20 as it reached out to provincial and territorial privacy commissioners to develop a joint statement on privacy principles used to assess contact-tracing applications. On that basis, the OPC in July 2020 conducted an in-depth privacy review of the federal government’s COVID-19 exposure notification application.

As I look back on the past year – and to the year ahead – I feel fortunate to have such talented, dedicated people working alongside me facing the daily challenges in these unprecedented times.

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Results at a glance and operating context

Results at a glance

In working towards the results below, in 2019-20, the OPC’s total actual spending was $28,547,260 and its total actual full-time equivalents (FTEs) was 193.

Actual spending

$28,547,260

193

Progress on performance indicators, as of March 31, 2020

Targets met or exceeded

Our Office met or exceeded four of its targets. These relate to the usefulness of our information, recommendations on privacy relevant bills and studies adopted, organizations’ knowledge of their privacy obligations, as well as the usefulness of our information and advice to both Canadians and federal and private sector organizations.

Targets not met

While we did not meet our target related to our service standards for responding to Canadians’ complaints, we did make important progress and reduced the gap between our result and the target by almost half over the previous year. Unfortunately, we saw a drop in the rate of compliance with our recommendations by departments and organizations, resulting in our target for the implementation of our recommendations not being met this year.

Targets set for March 2021

We made little progress towards our two targets set for 2021, namely, the development of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their obligations, and information for Canadians on how to exercise their rights. Despite our best efforts, we are unable to provide up-to-date guidance to organizations and Canadians on the vast majority of important privacy issues.

Operating context

The strategic and operating environment of the OPC is constantly evolving, given the rapidity of technological change, the range of new business models and the different means of data collection and processing. Current privacy legislation is ill-suited to meet these challenges. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic served to underline this deficiency.

For many years now, our Office has provided a detailed account to Parliament that Canadians need stronger, more enforceable federal privacy laws. We continue to live in a time of constant technological change. We see an increasing reliance on mass data collection and sharing, automated decision-making and profiling as generators of economic activity. The privacy implications and, by extension, risks to fundamental rights and freedoms, are immense. Technological advances in areas such as data analytics, artificial intelligence, robotics, genetic profiling and the Internet of Things raise novel and highly complex privacy risks.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in Canada in March, the urgency of limiting the spread of the virus posed a significant challenge for government and public health authorities who sought ways to leverage personal information to contain and gain insights about the novel virus and the global threat it presents.

The increase in use of digital technologies to go about our daily lives during the pandemic, as well as the increase in public-private partnerships has highlighted the shortcomings in our laws. The law is simply not up to protecting our rights in a digital environment. Risks to privacy and other rights are heightened by the fact that the pandemic is fueling rapid societal and economic transformation in a context where our laws fail to provide Canadians with effective protection. In light of concerns of this nature, in our last Annual Report to Parliament the Office put forth a blueprint for how to incorporate a rights-based framework into our laws. Incorporating a rights-based framework, along with effective enforcement mechanisms, would provide the necessary conditions to allow for responsible innovation and foster trust in government and business, giving individuals the confidence to fully participate in the digital age.

As part of Budget 2019, the OPC received funding to enhance its ability to deliver on its mandated obligations within the current legislative framework in the face of the exponential growth of the digital economy. This new funding has allowed us to work toward delivering optimal benefits to Canadians, ensuring that advice and guidance was provided to organizations on how to protect privacy. The funding also allowed us to address a very large part of our investigative backlog. These funds have helped, but are not sufficient for the Office to appropriately deal with the full volume/complexity of issues emerging on a daily basis which significantly impact the privacy rights of Canadians.

Finally, we cannot overlook the fact that our Office's operations were disrupted at the end of the year by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizationally, our Office was able to meet the challenge and remained fully functional and operational even though the majority of our employees worked remotely. We were able to cope with the additional workload resulting from COVID-19 response measures, and were able to provide advice and guidance on measures implemented by both government and the private sector to address the pandemic. However, this additional priority work related to the pandemic has required a considerable investment in both time and resources, which may impact the Office’s ability to work on other operational priorities in the coming year.

For more information on the OPC’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section in this report.

Results: what we achieved

This section describes, for each core responsibility, the results that the OPC achieved in 2019-20 and how OPC performed against the targets it set in its Departmental Plan for that year.

Core Responsibility

Protection of privacy rights

Description

Ensure the protection of privacy rights of Canadians; enforce privacy obligations by federal government institutions and private-sector organizations; provide advice to Parliament on potential privacy implications of proposed legislation and government programs; promote awareness and understanding of rights and obligations under federal privacy legislation.

Results

Due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of the year, our Office’s operations were disrupted and we saw a considerable growth in the workload of the Office. For instance, our interactions with public sector and government institutions significantly increased as they sought our advice on the privacy implications of initiatives in response to the pandemic. Our Office released a Framework to assess privacy impactful initiatives in response to COVID-19, and issued a joint statement with provincial and territorial privacy commissioners on privacy principles that should be respected during the use of any contact tracing application.

Beyond these year-end upheavals, the 2019-20 results achieved by the OPC under each of the Office’s Departmental Results are described below.

Departmental result 1: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

While we did not meet our target related to our service standards for responding to Canadians’ complaints in a timely manner, we did make important progress and reduced the gap between our result and the target by almost half (25 % to 14%) over the previous year. Indeed, we closed approximately 61% of our complaints within service standards, compared to 50% the previous year. Our goal is to reach the target of 75%. The combination of internal and external review of compliance processes, as well as streamlining and automation have yielded noticeable improvements to the timeliness in our responses in accordance with our service standards. We are optimistic that with these measures and the funding received, we will be able to reach our target.

Concurrent to our efforts to improve our service standards and with the allocation of additional funds flowing from Budget 2019, our Office was able to reduce the overall backlog of complaints older than 12 months by 50% from last year, and our goal is to reduce it by 90% by the end of 2021.

Our Office also measures the percentage of recommendations accepted and implemented by federal institutions and private sector organizations in a compliance context. In this past fiscal year, we have seen the number of recommendations accepted decline, from 96% to 80%.

This 16% decline from the previous year is, in part, related to the public sector, for which we adopted a stricter enforcement approach for Time Limit investigations, namely the “Deemed RefusalFootnote 1 Initiative.” While this initiative significantly reduces the delays in treating those types of investigations, we note that “deemed refusal” findings are issued in the face of resistance or lack of responsiveness from respondents when our Office recommends a commitment date to release the personal information of requesters under the Privacy Act. This compliance measure also empowers affected individuals to bring their matters before the Federal Court for review. Further, it better illustrates the level of cooperation, or lack thereof, from certain government institutions.

It should be noted that this result only speaks to privacy concerns that our Office is aware of. Our Office maintains that fundamental changes to our laws are required to protect citizens and restore balance in their relationship with organizations. Robust privacy laws are key to promoting trust in both government and commercial activities, and without that trust, innovation, and growth can be severely affected.

With respect to trust in the private sector, with the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica matter (now before the Federal Court), we saw an organization with millions of Canadian users reject our recommendations, which attracted significant public interest. While only a minority of Canadians trust that private sector organizations actually respect their privacy rights, the Cambridge/Analytica matter, as well as repeated and very large privacy breaches affecting tens of millions of Canadians, further erode that trust.

The Office continues to initiate or intervene in litigation cases that have the potential of advancing privacy law in Canada and are capable of having significant impact on the privacy interests of Canadians. In 2019-20 we filed a court application in relation to Facebook’s privacy practices; we continued to pursue the Reference proceeding we initiated in relation to PIPEDA’s application to Google’s search engine service; and were involved as an intervener in a case before the Supreme Court of Canada concerning the constitutionality of the Genetic Non-Discrimination Act, S.C. 2017, c. 3, which prohibits certain harmful practices relating to the collection, use and disclosure of genetic test results.

Departmental result 2: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

In this last year, we continued to produce guidance on a number of topics to inform Canadians on how to exercise their rights, and to guide organizations and federal institutions on how to meet their privacy obligations. In 2019-20 we completed 3 additional pieces of guidance from our list of 30 key privacy issues, including Receiving a privacy breach notification, Staying safe on social media and Expectations: OPC’S Guide to the Privacy Impact Assessment Process. All in all, so far, we have issued guidance on 27% of our planned list. We continue to work towards reaching our ambitious target of 90% by March 31, 2021 despite the fact that the exponential pace of technological change and the need to keep up and produce relevant and timely guidance continue to exceed our capacity.

Even though our guidance plan was developed with a view toward key privacy issues of relevance and currency, as part of our ongoing environmental scanning and external engagement, we keep abreast of new and emerging issues. To ensure that Canadians could rely on accurate and up-to-date information about their privacy rights, we updated 19 guidance documents. We also produced 15 additional guidance documents of various forms aimed at informing Canadians of their privacy rights and organizations of their privacy-related obligations. While they were not part of our list of 30 key privacy issues, these guidance documents were developed to respond to an emerging need (such as guidance on privacy and the COVID-19 outbreak) or to give tips and tools in user-friendly format (such as blog posts and videos) on practical topics affecting the everyday life of Canadians.

The sheer number of privacy issues for which businesses and individuals require the OPC’s guidance continues to multiply at a rapid rate. The challenge for our Office is to keep pace with the speed of technological advancements, when it is in a continual dynamic state of evolution. Unfortunately, despite our best efforts and the infusion of resources, most privacy issues continue to not be subject to up-to-date guidance or any guidance at all.

The OPC website is the primary communications channel between the organization and Canadians. Overall, 71% of those who respond to the web feedback tool found the information to be useful. However, only a minority of web visitors has given feedback. More attention is given to the qualitative feedback, which allows us to better understand Canadians’ needs and to update our webpages accordingly.

Departmental Result 3: Parliamentarians and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

We are pleased to note that this past year, 68% of our recommendations on various bills, studies and issues were adopted by Parliament.While this indicator provides some insight into the impact of our parliamentary work, it does not provide a complete picture. Importantly, it does not consider the absence of a fundamental law reform, advocated for several years now.

That said, we engaged with government officials in their work on law reform priorities. In December 2019, our Office provided recommendations to the Department of Justice as part of a comprehensive submission to its technical engagement on Privacy Act modernization. Following the last election, we also engaged with a number of newly appointed Ministers on privacy issues and law reform priorities.

On the private sector side, our Office carried out a range of compliance promotion activities, including advisory engagements. These activities are meant to engage businesses proactively to help guide them so that they can meet their privacy obligations. In all, our Office conducted 22 advisory engagements mostly with small and medium enterprises. This is obviously a very small number, and we encourage more businesses to seek our advisory services.

Besides the guidance work described earlier in this section of the report, we have also worked to implement our multi-year communications and outreach strategy to increase businesses’ awareness of privacy obligations. The material published on our website aimed specifically at organizations, such as guidance documents, interpretation bulletins and case summaries generated almost one million visits in 2019-20. We exhibited at 29 events and we delivered 74 speeches. These activities were then disrupted by the pandemic.

Furthermore, a telephone survey was administered to 1,003 companies across Canada from November 29, 2019 to December 19, 2019 to measure their awareness and understanding of their privacy obligations. 85% of private sector organizations rated their knowledge of privacy obligations as good or excellent. As in previous years, company size was the strongest predictor of a company’s privacy practices. Larger companies are more likely to have put in place a series of privacy practices, to have policies or procedures in place to assess privacy risks and to have a privacy policy. While a 85% awareness rate is very good, this is a self-reported assessment and we note that Canadians do not trust businesses to respect their privacy. Other results pointed to the need for more attention to privacy. Half of respondents (51%) said they make privacy information easily accessible to their customers. During the year, new information videos, aimed at small and medium-sized firms, were conceived and created to promote understanding of consent and how to deal with breaches of personal information. They are scheduled to be released in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

On the public sector side, our Office continued to review privacy impact assessments (PIAs) submitted by federal government institutions, and increased its consultations and interactions with government institutions outside of the formal PIA review process. Our goal is to provide timely advice that has an impact and improves privacy for Canadians and helps encourage a privacy by design approach to government services. On that front, we released an updated and easier to use guidance document for federal public sector institutions on how to comply with the Privacy Act and effectively manage privacy risks as part of the PIA process.

Overall, our Office strives to produce advice and guidance for federal and private sector organizations that helps them comply with their privacy obligations. We formally measured organization’s satisfaction level with the guidance provided by our Office. For the second year in a row, we have met our target of 70% with a result of 71% of federal and private sector organizations that found the guidance on our website useful.

In addition to the above, our Office continued to innovate and work smarter with the resources entrusted to us. Specifically, we have:

- continued to build internal capacity and invested in the groundwork for better use of data and business intelligence to drive decision-making and resource allocations in the future

- used technology to streamline certain processes, such as our revised online complaint form

- made greater use of risk management frameworks to prioritize work, address capacity issues and innovate in how we deliver quality services and results for Canadians, including exploring new technologies and approaches used in industry and government

- developed a Human Resources Strategic Plan 2020-2023 to effectively support the organization in achieving its mandate to ensure that the current and future workforce has the right skills and competencies to cope with a competitive, changing and rapidly evolving environment without boundaries

Results Achieved

The summary table below provides an overview of the results achieved against our targets set in the second year of implementation of our new Departmental Results Framework. This Framework, which took effect on April 1, 2018, includes a number of new indicators for which results for years prior to 2018-19 are not available. In those instances, actual results have been marked as “n/a.”

| Departmental Results | Performance Indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2017-18 Actual results |

2018-19 Actual results |

2019-20 Actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met. | Percentage of Canadians who feel their rights are respected. | n/a | Baseline year | n/a | 46.5%Footnote 2 | Not a survey year |

| Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards. | 75% | March 31, 2020 | 54% | 50% | 61% | |

| Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations. | 85% | March 31, 2020 | n/a | 96% | 80% | |

| Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights | Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights. | 70% | March 31, 2021 | Not a survey year | 64% | Not a survey year |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | n/a | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 27% (8/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | |

| Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful. | 70% | March 31, 2020 | n/a | 72% | 71% | |

| Parliamentarians, and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights | Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted. | 60% | March 31, 2020 | n/a | 35% (33 recs made, 11 adopted) | 68% (28 recs made, 19 adopted) |

| Percentage of private sector organizations that have good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations. | 85% | March 31, 2020 | 82% | Not a survey year | 85% | |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | n/a | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 27% (8/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | |

| Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance. | 70% | March 31, 2020 | n/a | 73% | 71% |

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2019-20 Main Estimates |

2019-20 Planned spending |

2019-20 Total authorities available for use |

2019-20 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2019-20 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18,104,213 | 18,104,213 | 21,740,131 | 20,573,425 | 2,469,212 |

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2019-20 Planned full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Actual full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 133 | 142 | 9 |

The variance between the planned and actual full-time equivalents in 2019-20 is mainly due to resources received from the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians. It also accounts for normal turnover in staff.

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are:

- Acquisition Management Services

- Communications Services

- Financial Management Services

- Human Resources Management Services

- Information Management Services

- Information Technology Services

- Legal Services

- Materiel Management Services

- Management and Oversight Services

- Real Property Management Services

At the OPC the communications services are an integral part of our education and outreach mandate. As such, these services are included in the Promotion Program. Similarly, the OPC’s legal services are an integral part of the delivery of compliance activities and are therefore included in the Compliance Program.

Results

The OPC’s internal services functions continued to deliver high-quality and timely advice and services across the organization, in support of organizational goals.

In 2019-20, these functions also played a vital role in support of several activities including:

- Supporting the organization in building internal capacity with temporary and permanent funding increases received through the 2019 federal budget

- Promoting a culture of results and reliance on performance and business information to inform management decision-making

- Pursuing the implementation of the OPC’s updated Information Management and Information Technology (IM/IT) strategies

- Continuing the exploration of partnerships with other agents of Parliament to gain effectiveness, share knowledge and implement best practices in areas such as IT, administrative services, people management and human resources programs

- Contributing to TBS/PSPC measures to the HR-to-Pay Stabilization Initiative and also issuing pay to employees

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2019-20 Main Estimates* |

2019-20 Planned spending* |

2019-20 Total authorities available for use |

2019-20 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2019-20 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,610,661 | 6,610,661 | 8,451,286 | 7,973,835 | 1,363,174 |

| * Includes Vote Netted Revenue authority (VNR) of $200,000 for internal support services to other government organizations | ||||

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2019-20 Planned full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Actual full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 48 | 51 | 3 |

The variance between the planned and actual full-time equivalents in 2019-20 is mainly due to resources received from the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians. It also accounts for normal turnover in staff.

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

Actual expenditures

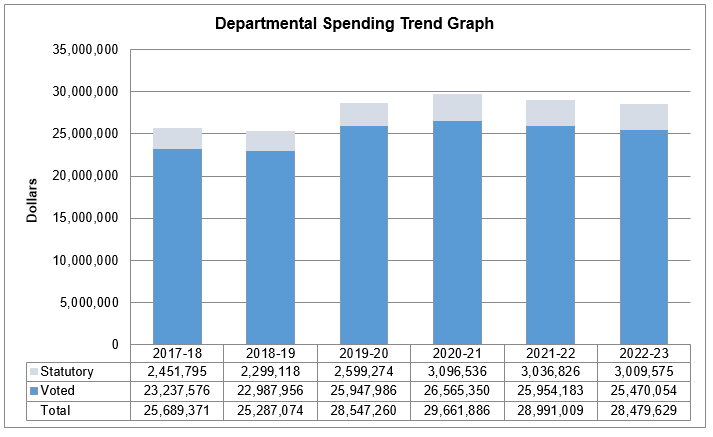

Departmental spending trend graph

The following graph presents planned (voted and statutory spending) over time.

Text version of Figure 1

| Fiscal year | Total | Voted | Statutory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 25,689,371 | 23,237,576 | 2,451,795 |

| 2018-19 | 25,287,074 | 22,987,956 | 2,299,118 |

| 2019-20 | 28,547,260 | 25,947,986 | 2,599,274 |

| 2020-21 | 29,661,886 | 26,565,350 | 3,096,536 |

| 2021-22 | 28,991,009 | 25,954,183 | 3,036,826 |

| 2022-23 | 28,479,629 | 25,470,054 | 3,009,575 |

The graph above illustrates the OPC’s spending trend over a six-year period from 2017-18 to 2022-23. Fiscal years 2017-18 to 2019-20 reflect the organization’s actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts. Fiscal years 2020-21 to 2022-23 represent planned spending.

The overall spending trend in the graph illustrates an increase from 2017-18 to 2019-20. The OPC’s spending in 2019-20 increased by $3.3 million compared to 2018-19. This increase is primarily explained by the new funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians. The Office received funding to enhance its capacity, including its ability to engage with Canadian individuals and businesses, address complaints and respond to privacy issues as they occur.

Starting fiscal year 2021-22, OPC’s planned spending will decrease due to the sunset funding received in 2019-20 and 2020-21 to reduce the backlog of privacy complaints older than one year, and give Canadians more timely resolution of their complaints.

Budgetary performance summary for Core Responsibilities and Internal Services (dollars)

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2019-20 Main Estimates |

2019-20 Planned spending |

2020-21 Planned spending |

2021-22 Planned spending |

2019-20 Total authorities available for use |

2017-18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2018-19 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2019-20 Actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Compliance | * | * | * | * | * | 12,112,252 | * | * |

| 1.2 Research and policy development | * | * | * | * | * | 3,797,155 | * | * |

| 1.3 Public outreach | * | * | * | * | * | 2,770,740 | * | * |

| Protection of privacy rights | 18,104,213 | 18,104,213 | 21,700,691 | 21,076,464 | 21,740,131 | * | 18,504,642 | 20,573,425 |

| Subtotal | 18,104,213 | 18,104,213 | 21,700,691 | 21,076,464 | 21,740,131 | 18,680,147 | 18,504,642 | 20,573,425 |

| Internal Services | 6,610,661 | 6,610,661 | 7,961,195 | 7,914,545 | 8,451,286 | 7,009,224 | 6,782,432 | 7,973,835 |

| Total | 24,714,874 | 24,714,874 | 29,661,886 | 28,991,009 | 30,191,417 | 25,689,371 | 25,287,074 | 28,547,260 |

| * In 2018-19, the OPC started reporting under its core responsibilities reflected in the Departmental Results Framework. | ||||||||

For fiscal years 2017-18 to 2019-20, actual spending represents the actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts of Canada. Fiscal years 2020-21 to 2021-22 represent planned spending.

The net increase of $5.5 million between the 2019-20 total authorities available for use ($30.2 million) and the 2019-20 planned spending ($24.7 million) is mainly due to funding received for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians as well as the operating budget carry forward exercise, compensation related to the new collective bargaining and adjustments to the employee benefit plans.

Total authorities available for use in 2019-20 ($30.2 million) compared to actual spending ($28.6 million) resulted in a lapse of $1.6 million. This amount represents the operating lapses reported in the Public Accounts of Canada by the OPC.

Actual human resources

Human resources summary for Core Responsibilities and Internal Services

| Core Responsibility and Internal Services |

2017-18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Actual full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Planned full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Actual full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Planned full-time equivalents |

2021-22 Planned full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection of Privacy Rights | 123 | 123 | 133 | 142 | 159 | 153 |

| Subtotal | 123 | 123 | 133 | 142 | 159 | 153 |

| Internal Services | 50 | 50 | 48 | 51 | 54 | 54 |

| Total | 173 | 173 | 181 | 193 | 213 | 207 |

| * In 2018-19, the OPC started reporting under its core responsibilities reflected in the Departmental Results Framework. | ||||||

The increase in full-time equivalent (FTE) in 2019-20 and future years is mainly due to resources received from the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians. The variance between the actual FTEs in 2019-20 and planned FTEs for future years is due to the ramping up of staffing to implement Budget 2019 measures, as well as normal turnover in staff.

The OPC took measures to ensure staffing processes were launched as quickly as possible following the funding approval. We used accelerated staffing strategies and leveraged from existing pools when possible. By the end of the third quarter of fiscal year 2019-20, the OPC had increased its staff complement to expected levels and is in a good position to meet its targets for future years.

Expenditures by vote

For information on the OPC’s organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2019-20.

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of the OPC’s spending with the Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available in the GC InfoBase.

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The OPC’s financial statements (audited) for the year ended March 31, 2020, are available on its website.

Financial statement highlights

The financial highlights presented below are drawn from the OPC’s financial statements, which are prepared on an accrual accounting basis while the planned and actual spending amounts presented elsewhere in this report are prepared on an expenditure basis. As such, amounts differ.

Condensed Statement of Operations (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2020 (dollars)

| Financial information | 2019-20 Planned results |

2019-20 Actual results |

2018-19 Actual results |

Difference (2019-20 Actual results minus 2019-20 Planned results) |

Difference (2019-20 Actual results minus 2018-19 Actual results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 28,840,874 | 32,595,096 | 28,615,898 | 3,754,222 | 3,979,198 |

| Total revenues | 200,000 | 193,662 | 173,665 | (6,338) | 19,997 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers |

28,640,874 | 32,401,434 | 28,442,233 | 3,760,560 | 3,959,201 |

In 2019-20, actual expenses were higher than the 2018-19 actual expenses primarily due to the new funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians. The increases in expenditures are related to salary expenses due to the additional staffing and salary increases following the ratification of collective agreements. It is also explained by the increase in guidance work, investments made during the implementation of OPC’s updated IM/IT strategies, staffing support services, additional software licenses and acquisition of informatics technology equipment.

The OPC provides internal support services to other small government departments related to the provision of IT services. Pursuant to section 29.2 of the Financial Administration Act, internal support services agreements are recorded as revenues. In 2019-20, the actual revenues were higher than the 2018-19 actual revenues due to increased services provided to current clients.

Condensed Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) as of March 31, 2020 (dollars)

| Financial information | 2019-20 | 2018-19 | Difference (2019-20 minus 2018-19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 5,655,324 | 5,886,223 | (230,899) |

| Total net financial assets | 3,806,741 | 4,327,911 | (521,170) |

| Departmental net debt | 1,848,583 | 1,558,312 | 290,271 |

| Total non-financial assets | 2,182,293 | 2,468,377 | (286,084) |

| Departmental net financial position | 333,710 | 910,065 | (576,355) |

The decrease in net liabilities of $0.2 million is mainly explained by a reduction in the year-end accounts payable as a result of the OPC continuing to improve its processes and internal controls for timely processing and a decrease of transactions towards year-end due to the COVID-19 crisis.

The decrease in net financial assets of $0.5 million is mainly due to a decrease in the Due from Consolidated Revenue Fund (the result of the decrease in liabilities), which represents amounts that may be disbursed without further charges to the OPC’s authorities offset by an increase of accounts receivable and advances.

The total non-financial assets of $2.2 million consists primarily of tangible capital assets. The decrease of $0.3 million is mainly attributable to the annual depreciation expense, which was greater than the acquisitions made during the year for additional informatics hardware and leasehold improvements.

Additional information

Organizational profile

Appropriate MinisterFootnote 3: David Lametti

Institutional Head: Daniel Therrien

Ministerial portfolioFootnote 4: Department of Justice Canada

Enabling Instrument(s): Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21; Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C. 2000, c.5

Year of Incorporation / Commencement: 1982

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

“Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do” is available on the OPC’s website.

Reporting framework

The OPC’s Departmental Results Framework and Program Inventory of record for 2019-20 are shown below.

Core Responsibility: Protection of Privacy Rights

Departmental Result: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel their privacy rights are respected

- Indicator: Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards

- Indicator: Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations

Departmental Result: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful

Departmental Result: Parliamentarians, and federal- and private-sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted

- Indicator: Percentage of private sector organizations that have a good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities

- Indicator: Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance

Program Inventory

- Compliance Program

- Promotion Program

Internal Services

Supporting information on the program inventory

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the OPC’s website.

- Departmental sustainable development strategy

- Gender-based analysis plus

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures. This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs. The tax measures presented in this report are the responsibility of the Minister of Finance.

Organizational contact information

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

Canada

Telephone: 819-994-5444

Toll Free: 1-800-282-1376

Fax: 819-994-5424

TTY: 819-994-6591

Website: www.priv.gc.ca

Appendix: definitions

- appropriation (crédit)

- Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

- budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

- Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

- core responsibility (responsabilité essentielle)

- An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a core responsibility are reflected in one or more related departmental results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

- Departmental Plan (plan ministériel)

- A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a 3-year period. Departmental Plans are usually tabled in Parliament each spring.

- departmental priority (priorité)

- A plan or project that a department has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired departmental results.

- departmental result (résultat ministériel)

- A consequence or outcome that a department seeks to achieve. A departmental result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

- departmental result indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

- A quantitative measure of progress on a departmental result.

- departmental results framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

- A framework that connects the department’s core responsibilities to its departmental results and departmental result indicators.

- Departmental Results Report (rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

- A report on a department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

- experimentation (expérimentation)

- The conducting of activities that seek to first explore, then test and compare the effects and impacts of policies and interventions in order to inform evidence-based decision-making, and improve outcomes for Canadians, by learning what works, for whom and in what circumstances. Experimentation is related to, but distinct from innovation (the trying of new things), because it involves a rigorous comparison of results. For example, using a new website to communicate with Canadians can be an innovation; systematically testing the new website against existing outreach tools or an old website to see which one leads to more engagement, is experimentation.

- full-time equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

- A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person year charge against a departmental budget. For a particular position, the full-time equivalent figure is the ratio of number of hours the person actually works divided by the standard number of hours set out in the person’s collective agreement.

- gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS+])

- An analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and gender-diverse people experience policies, programs and services based on multiple factors including race ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.

- government-wide priorities (priorités pangouvernementales)

- For the purpose of the 2019-20 Departmental Results Report, those high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the 2019 Speech from the Throne, namely: Fighting climate change; Strengthening the Middle Class; Walking the road of reconciliation; Keeping Canadians safe and healthy; and Positioning Canada for success in an uncertain world.

- horizontal initiative (initiative horizontale)

- An initiative where two or more federal organizations are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

- non-budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

- Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

- performance (rendement)

- What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

- performance indicator (indicateur de rendement)

- A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

- performance reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement)

- The process of communicating evidence based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

- plan (plan)

- The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally, a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead to the expected result.

- planned spending (dépenses prévues)

- For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts presented in Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports. - program (programme)

- Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

- program inventory (répertoire des programmes)

- Identifies all the department’s programs and describes how resources are organized to contribute to the department’s core responsibilities and results.

- result (résultat)

- A consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

- statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives)

- Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

- target (cible)

- A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

- voted expenditures (dépenses votées)

- Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an appropriation act. The vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.

Alternate versions

- PDF (766 KB) Not tested for accessibility

- Date modified: