Annual Reports to Parliament 2004 on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 995-8210, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2005

Cat. No. IP51-1/2005

ISBN 0-662-68986-0

This publication is also available on our Web site at www.priv.gc.ca, in addition to our 2004-2005 Annual Report on the Privacy Act.

October 2005

The Honourable Daniel Hays, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2004.

Yours sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

October 2005

The Honourable Peter Milliken, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2004.

Yours sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Foreword

The year 2004 saw the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) reach maturity, with the Act extending across the country to all commercial activities, except in provinces with legislation deemed substantially similar. British Columbia, Alberta and Quebec have enacted private sector privacy legislation that has been deemed substantially similar to PIPEDA. PIPEDA applies to federal works, undertakings and businesses across the country, as well as to interprovincial and international transactions.

The maturing of PIPEDA is cause for some celebration. Canadians now have comprehensive rights relating to personal information in the private sector in Canada, in addition to longstanding protections in the public sector through the Privacy Act and its provincial equivalent legislation. That is not to say that either the private sector or public sector privacy laws fully protect the privacy rights of Canadians in every sense. They do not. But much of the essential framework for protecting those rights is now in place. Our Office will continue to enforce and analyze the application of PIPEDA to ensure that Canadians are well-served by it, and that the Canadian private sector understands and respects its obligations under the Act. We will continue to help the business community comply with it, and develop the best practices which will minimize burden and clarify expectations.

Interjurisdictional challenges

As with any relatively new legislation, problems can emerge. Where a province has enacted legislation that is substantially similar to all or part of PIPEDA , confusion may arise about which law — provincial or federal — will apply to certain information-handling practices. In other cases, the laws of two jurisdictions may be involved in addressing an issue. Some elements of the handling of personal information may be subject to a provincial law — the collection of the information within a province, for example — while another element, such as the transborder disclosure of the information, may fall under PIPEDA.

However, the dust is beginning to settle around these jurisdictional issues due to concerted efforts by our Office, our provincial counterparts and industry. We are working with our provincial colleagues to streamline investigations where provincial and federal jurisdictions both apply. It is not our intention to make life difficult for those who must comply with the various privacy laws in Canada, and we clearly do not want to waste the limited resources available to privacy commissioners across Canada by duplicating efforts in conducting investigations and developing policy.

A complex and changing universe

There are many powerful forces in the universe in which we assert our privacy rights — galloping advances in surveillance and data-handling technologies, global competition in business which drives companies to obtain and use more personal information about customers and personnel, and the government imperative to acquire personal information to enhance administrative efficiency and respond to the security concerns of our world. Those of us attempting to protect this fundamental right must call out strongly for a debate that can be at times unpopular and demands a wealth of expertise in ever more complex fields of research. It is a challenge to keep up.

It is important to remember that information is power, and holding the personal information of individuals conveys power to the holder. One complexity that we have been grappling with this year stems from a convergence of two phenomena which are not new by any means, but which have reached a critical point. "Outsourcing" of data processing operations and call centres results in the personal information of Canadian residents or customers of Canadian companies being transferred and processed outside Canada. The thirst of foreign governments, particularly that of the United States and its allies in the war on terror, for access to personal information for "security" purposes means that the outsourced data may be accessed for law enforcement or national security purposes, outside our jurisdiction and the protection of our laws and our Court system.

Transborder data flow has been discussed in Canada since the 1960s. The original report on Privacy and Computers, published in 1972 by the Departments of Communications and Justice, dealt with the matter extensively, including matters of sovereignty. The issue prompted the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to meet and develop the first Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data in 1980, and it drove the European Union to pass its Directive 95/46/EC on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Yet we know very little about the details of transborder flows of personal information about Canadian residents and customers.

The current interest in the USA PATRIOT Act has raised an issue that has been lurking beneath the surface for decades — the extent to which Canadian businesses, and governments in Canada, should share personal information with foreign governments. The discussion is far from over. In fact, it is just beginning. Our Office endorsed many of the recommendations of the B.C. Information and Privacy Commissioner, David Loukidelis, on issues of transborder flows of personal information and we will continue working to ensure Canadians' privacy protections remain in place.

This Office is tasked with protecting privacy in Canada. We cannot do the job alone, we depend on all players in society to contribute to preserving the freedoms and rights which are an intrinsic part of Canada's rich fabric and history. The complexity of the current privacy environment has led our Office to launch a Contributions Program to help develop a national privacy research capacity in Canada. The findings of this first round of research projects will be available in 2005. These research findings will complement the existing policy research function within our Office, and in a modest way help to enrich the community of privacy scholarship in Canada.

Responding to a greater need

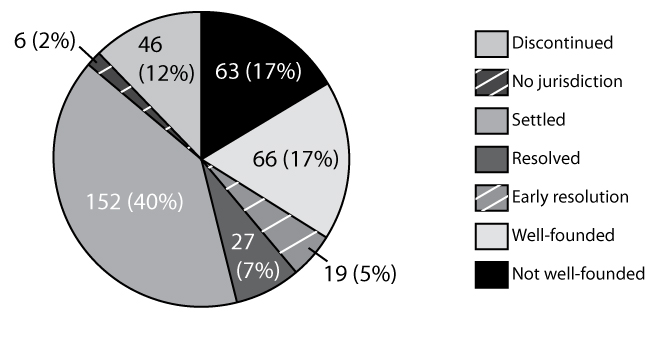

This Office received 723 complaints under PIPEDA between January 1 and December 31, 2004, more than double the 302 received in the previous calendar year. We closed 379 complaints, significantly more than the 278 cases closed in 2003. While the debate about the merits of having the Commissioner continue to operate as an ombudsman versus giving the Commissioner order-making powers remains, it is clear that our Office has accomplished much that is positive using the current ombudsman approach. Some 40 per cent of the complaints closed during the year were settled, and another seven per cent resolved — an indication that suasion, a prominent feature of the ombudsman approach, is an effective tool.

We have introduced a formal procedure of systematic follow-ups to complaint investigations under PIPEDA. We will now be in position to monitor the progress of organizations in implementing commitments they make during complaint investigations and in response to the recommendations our Office issues to them. Equally important, our Audit and Review Branch is strengthening its capacity to audit organizations subject to PIPEDA.

We faced many challenges in 2004, challenges that will only increase in frequency and complexity. This is not a time for those concerned about this fundamental human right called privacy to shrink from speaking out, from debate or from controversy. We will seize the opportunity of the 2006 review of PIPEDA to make recommendations about how to improve and better enforce the two pieces of legislation that we oversee, Although the Act is still very new in application, the dynamic environment of information policy demands that we keep current and try to ensure that the legislation also responds effectively to current threats. We are developing a list of improvements and suggestions for change, and we are confident that in another five years, when the next review is due, there will be more changes necessary. Parliament was wise to insist on periodic review of this legislation, and we will continue to push for review of the Privacy Act and inclusion of such a review mechanism in it.

This year, we have published two separate reports, dividing the Privacy Act from the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). We felt this was more appropriate given that the Privacy Act requires us to report on the fiscal year (2004-2005), while under PIPEDA we are required to report on the calendar year (2004). As well, each Act provides a separate framework for investigations and audits. Both our reports detail efforts we have taken to meet the growing demands on our Office to act as the guardians of privacy for Canadians on behalf of Parliament. There is much overlapping between these reports because many of our activities are not particular to one law or another and, increasingly, the policy issues are common across the two regimes.

Our Multi-Faceted Mandate

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner oversees two laws — the Privacy Act, which applies to federal government institutions, and PIPEDA, which governs personal information management in commercial activities.

Parliament requires our Office to ensure that both the federal public sector and private sector (in most provinces) are held accountable for their personal information handling, and that the public is informed about privacy rights. The mandate is not always well understood.

As an independent ombudsman, we are:

- An investigator and auditor with full powers to investigate and initiate complaints, conduct audits and verify compliance under both Acts;

- A public educator and advocate with a responsibility both to sensitize businesses about their obligations under PIPEDA and to help the public better understand their data protection rights;

- A researcher and expert adviser on privacy issues to Parliament, government and businesses; and

- An advocate for privacy principles involved in litigating the application and interpretation of the two privacy laws. We also analyze the legal and policy implications of bills and government proposals.

Policy Perspective

In 2004, our major preoccupations in the policy area were the heightened demands for personal information in the name of national security, the transborder flow of personal information, and that hardy perennial, privacy invasive technologies. From cell phones in locker rooms to global positioning systems in cars, the need to measure the impact of these new technologies and read the privacy law into their design and application is an ongoing challenge.

Technology

During the past year, the privacy implications of using Radio Frequency Identification Devices (RFIDs) as tracking devices have become increasingly prominent. RFIDs encompass technologies that use radio waves to read a serial number stored on a microchip. The microchip or tag can be placed in military equipment, passports, clothing, currency notes, vehicles, tires, pass cards and just about anything else sold in the marketplace, including food and drink packages. RFID applications include tracking goods from the manufacturer to the retail store, tracking people in a health institution or monitoring the movements of schoolchildren.

Depending on its individual design, an RFID can transmit information over long distances or only a few centimeters. It may hold no personal information or store extensive personal information, including biometrics. An RFID can be "active" or "passive" — active where it has its own power to broadcast information to a reader, or passive in that it lies dormant until awakened by a signal from a "reader."

The combination of tags, (sometimes smaller than a grain of rice or built invisibly into the paper of a product), powerful coding and advanced computer systems has created enormous economic incentives for companies to introduce RFID technology. A recent market forecast predicts that the global value of the total RFID tag market will expand from $1.95 billion in 2005 to $26.9 billion in 2015. Given that each RFID tag may eventually cost only pennies, the potential scale of use is greater than almost any other single technology.

Organizations must think carefully about the legal implications of deploying RFID systems. Amidst the flurry of activity involving RFIDs, very few people fully understand the myriad of privacy implications. We are now encountering many marketplace uses of RFIDs, and expect that we will soon be investigating complaints about tracking the use of RFIDs.

Similarly, although there have been some interesting stories in the press about the use and abuse of global positioning technology, most individuals are unaware of the data that is accumulated by such devices. Fortunately, PIPEDA contains an innovative provision requiring openness with respect to information practices.

Organizations placing global positioning devices in consumer goods or conveyances (rental cars, for example) must identify what the device does, the data it collects, how long the data is kept, and who has access to it.

We are entering a world where computing power will be present in the most ordinary day-to-day devices. If we are not careful, that power will be used to gather or broadcast personal information in ways that greatly diminish our privacy, not to mention our autonomy and human dignity. As transmitting devices are built into roadsides, licence plates, currency and books, we are hard pressed to keep up with the potential privacy invasions and abuses. Canadians need to become more aware of and participate in discussing the privacy issues that flow from these developments. We need to shape our future into something that reflects the rights and freedoms we cherish today. From Reginald Fessenden to Marshall McLuhan, Canadians have shown leadership in the development of communications technologies and in communications theory. We are confident we can now rise to the current challenge, and demonstrate how we can use these powerful devices, in the world of ubiquitous computing and communications, yet maintain respect for that most fundamental of human values, privacy.

Parliament's Window on Privacy

The Privacy Commissioner of Canada is an Agent of Parliament who reports directly to the Senate and the House of Commons. As such, the OPC acts as Parliament's window on privacy issues. Through the Commissioner, Assistant Commissioners and other senior OPC staff, the Office brings to the attention of Parliamentarians issues that have an impact on the privacy rights of Canadians. The OPC does this by tabling Annual Reports to Parliament, by appearing before Committees of the Senate and the House of Commons to comment on the privacy implications of proposed legislation and government initiatives, and by identifying and analyzing issues that we believe should be brought to Parliament's attention.

The Office also assists Parliament in becoming better informed about privacy, acting as a resource or centre of expertise on privacy issues. This includes responding to a significant number of inquiries and letters from Senators and Members of Parliament.

Appearances before Parliamentary Committees

Appearances before committees of the Senate and the House of Commons constitute a key element of our work as Parliament's window on privacy issues. During the period covered by this report, the Privacy Commissioner and other senior OPC staff appeared nine times before Parliamentary committees: six times on bills with privacy implications and three times on matters relating to the management and operations of the Office.

The OPC appeared on the following bills before Parliamentary committees in 2004:

- Bill C-6, the Assisted Human Reproduction Act (March 3, 2004)

- Bill C-7, the Public Safety Act, 2002 (March 18, 2004)

- Bill C-2, An Act to Amend the Radiocommunication Act (May 6, 2004)

- Bill C-12, the Quarantine Act (November 18, 2004)

- Bill C-22, An Act to establish the Department of Social Development and to amend and repeal certain related Acts (December 9, 2004)

- Bill C-23, An Act to establish the Department of Human Resources and Skills Development and to amend and repeal certain related Acts (December 9, 2004)

- Bill C-11, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (December 14, 2004)

Regarding the management and operations of the Office, OPC officials appeared before Parliamentary committees on the following matters in 2004:

- Annual Report and Main Estimates 2003-2004 (November 17, 2004)

- Supplementary Estimates (December 1, 2004)

Other Parliamentary Liaison Activities

The OPC has undertaken a number of other initiatives over the course of the past year to improve its ability to advise Parliament on privacy matters.

In May 2004, we created a dedicated Parliamentary liaison function within the Office to improve our relationship with Parliament. This function resides in the Research and Policy Branch, reflecting the OPC's desire to focus its Parliamentary affairs activities on providing in-depth and accurate policy advice to Senators and Members of Parliament.

Improving on how we assess, monitor and forecast Parliamentary activity has been a priority for us in the past year. The OPC put in place a new and improved system for monitoring the status of bills on Parliament Hill, as well as keeping tabs on new and emerging developments of interest to privacy promotion and protection. Our goal is to build bridges to departments so that we can comment earlier in the legislative process, when our criticisms could be dealt with more effectively. It is often too late when a bill has been introduced in the House of Commons, to rethink approaches to information issues.

The Office has responded to a significant number of inquiries and letters from Senators and MPs this year, and the Commissioner and Assistant Commissioners have also met privately with Senators and MPs who wished to discuss policy matters relating to privacy, or wanted to know more about the operations of the Office.

In late 2004, the OPC in conjunction with the Office of the Information Commissioner, and in collaboration with the Research Branch of the Library of Parliament, held an information session for Parliamentarians and their staff on the roles and mandates of both Offices. This information session was well attended and raised many questions among participants. We believe such information sessions contribute to increasing awareness of privacy issues on Parliament Hill, and look forward to holding more such sessions in the future.

Priorities for the Coming Year

The Office expects to be busy in the area of Parliamentary affairs over the next fiscal year. There are a number of bills of interest to us expected in the upcoming session, and the statutory review by Parliament of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act is expected to start in 2006. The OPC plans to play a constructive role during this review, by providing thoughtful advice to Parliamentarians mandated with studying at how the Act has worked over the course of its first years of implementation, and how it may be modified and improved.

The OPC will continue to follow with interest the Parliamentary review of the Anti-terrorism Act. The Privacy Commissioner appeared twice before committee on this matter in fiscal year 2005-06 — once before a Senate special committee reviewing the Act (May 9, 2005), and on another occasion before a sub-committee of the Commons Standing Committee on Justice (June 1, 2005).

We recognize that to act as an effective Agent of Parliament we need to have good working relationships with federal departments and agencies. The OPC plans to put more emphasis on identifying and raising privacy concerns when government initiatives are being developed rather than waiting until they reach Parliament, as this increases the possibility that privacy concerns will be taken into account.

National Security

In May 2004, the Public Safety Act, 2002 was enacted. The Act, first introduced in November 2001 in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, allows the Minister of Transport, the Commissioner of the RCMP and the Director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), without a warrant, to compel air carriers and operators of aviation reservation systems to provide information about passengers. While this may seem reasonable given the risks that terrorists pose to air transport, authorities are not using this information exclusively for anti-terrorism and transportation safety. The Public Safety Act, 2002 also allows the information to be used to identify passengers for whom there are outstanding arrest warrants for a wide range of lesser criminal offences. In other words, the machinery of anti-terrorism is being used to meet the needs of ordinary law enforcement, lowering the legal standards that law enforcement authorities in a democratic society must normally meet.

The retention and mining of private sector data collections by government sends a troubling signal to private sector organizations trying to comply with privacy legislation. If the government can use data to manage risks from unknown individuals, why can't the private sector? Private sector companies are cutting down on data collection to comply with PIPEDA , but now the government is asking them to retain it so that they can access it for government purposes. PIPEDA sets a high bar for organizations with respect to using and disclosing personal information without consent for the purposes of investigating fraud and other illegal activities that have an impact, while the standards that government must meet under the Privacy Act are much less rigorous.

In 2004, our Office raised concerns about a provision in the Public Safety Act, 2002 that amends PIPEDA. The amendment allows organizations subject to PIPEDA to collect personal information, without consent, for the purposes of disclosing this information to government, law enforcement and national security agencies if the information relates to national security, the defence of Canada or the conduct of international affairs. Allowing private sector organizations to collect personal information without consent in these circumstances effectively co-opts them into service for law enforcement activities. This dangerously blurs the line between the private sector and the state. We comment more extensively on public safety issues in the Privacy Act Annual Report, but this is also an important issue under PIPEDA because of the potential for inappropriate manipulation of private sector data to serve state interests.

The 2001 Anti-terrorism Act contained a provision requiring a review after three years. The Senate has appointed a special committee to conduct its review. The House of Commons review is being conducted by the Subcommittee on Public Safety and National Security, a subcommittee of the Standing Committee on Justice, Human Rights, Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness. However, the Commons Committee is not looking at the many other pieces of legislation that were also enacted or amended in the wake of the terrorist attacks. Many of these laws contain extensive powers to intrude and should be examined as well.

The Official Secrets Act was replaced by the Security of Information Act in 2001. Section 10 of the new Act allows the deputy head of a department, on the issuance of a certificate, to bind members of the private sector to secrecy for life with respect to methods of investigation or special operations. We understand that sometimes it is necessary to deal with threats to our national security and critical infrastructure, but we raise the warning flag when we see new powers without complementary oversight provisions to ensure accountability. We have raised the issue of accountability and oversight in our submission to Parliament on the review of the Anti-terrorism Act , but this particular provision is in the Security of Information Act , and we think it merits public reporting on how often it is being used.

In the war on terror, governments have made it clear that they must have the cooperation of the private sector to ensure public safety and the security of the critical infrastructure. From the perspective of this Office, we must also ask whether we can effectively oversee the private sector and the role it might play in security matters. In the United States, the use of private sector databases and information retention for law enforcement and anti-terrorism continue to attract criticism. We do not know the extent to which such use and retention occurs in Canada, but it is an issue of growing concern to Canadians and we are trying to get answers so that we can respond to their queries and complaints.

In July 2004, Canada began enforcing new marine security requirements under the International Maritime Organization's International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code. To further enhance port security, Transport Canada is proposing to introduce a controversial Marine Facilities Restricted Area Access Clearance Program to screen port workers who have access to restricted areas. This screening process will involve collecting significant amounts of personal and potentially sensitive information about as many as 30,000 port workers. Once again, the extent to which such security checks are dependent on private sector information databases is of interest to our Office.

The issue of data-matching is an old one that has pre-occupied privacy scholars and oversight bodies for over twenty years. Technology has advanced, and we really no longer speak of data-matching but rather data-mining. There are many invisible uses of integrated information systems that collect and analyze significant amounts of personal information related to our travel patterns, our financial transactions, and even the people with whom we associate. Many of these systems would be viewed by consumers as immensely positive, were they to know of them and fully understand them because they provide faster loan approvals, instant recognition of credit card theft, and better customer service. However, these systems also now analyze deep reservoirs of personal information in an attempt to find patterns that might suggest that an individual is a security threat, a money launderer or is engaged in financing a terrorist group.

As law enforcement and national security agencies collect more information from more sources about more individuals, the chances increase that decisions will be based on information of questionable accuracy, or that information will be taken out of context.

When personal information is misused, misinterpreted or inappropriately disclosed it can have serious adverse consequences for individuals, families, and even communities. The problem is aggravated when, because of secrecy provisions and a lack of transparency, we cannot find out where the system broke down or on what basis individuals were wrongly targeted.

Outsourcing and Transborder Flows of Personal Information

The transfer of personal information from Canada into foreign jurisdictions (transborder data flows) is another issue as old as privacy legislation itself. Scholars and government policy experts in the 1960s and 70s anticipated greater flows of data in the future as communications technology improved. Whether they could have predicted the enormity of the global flow of data that we see today is another question.

In 2004, the transborder issue became more visible in Canada when a complaint was raised in British Columbia about the outsourcing of health information processing from the B.C. government to a U.S.-linked company operating in the province. The B.C. Government Employees Union alleged that the information would be available to the U.S. government under the expansive search powers introduced in 2001 by the USA PATRIOT Act. Although there have been many high profile instances of outsourcing in recent years, with occasional concern about the privacy implications, this appeared to be the first where a specific piece of legislation was singled out as a threat. The B.C. Information and Privacy Commissioner, David Loukidelis, took the step of issuing a call for public comment on this issue, and we submitted a brief in response.

Our submission explained that a company holding personal information in Canada about Canadian residents was not required to provide the information to a foreign government or agency in response to a direct court order issued abroad. In fact, the organization in Canada would in many cases violate PIPEDA if it disclosed the information without the consent of the individuals to whom the information relates.

However, there would be no violation of PIPEDA , for example, if the organization disclosed the information under Canadian legislation such as the Aeronautics Act provision that allows Canadian air carriers to disclose passenger information to foreign states.

We also concluded that an organization operating in a foreign country and that holds personal information about Canadians in that country must comply with the laws of that country. This means that when a Canadian organization outsources the processing of personal information to a company in the United States or another country, that information may be accessible under the laws of those countries.

The foreign government could of course request the same information through a mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) and ask the federal Department of Justice to arrange for Canadian law enforcement agencies to obtain the information from corporations in Canada for them — a system of government-to-government cooperation that predates the USA PATRIOT Act.

PIPEDA deals succinctly with transborder data flows in Principle 4.1.3 of the Schedule to the Act. This principle requires that information transferred for processing must be protected at a level "comparable" to that provided by PIPEDA. However, when data is held or processed outside Canada there is a loss of control over what a foreign jurisdiction might do with that information and our Office has no oversight authority.

We urgently need to address these flows of personal information so that we can ensure protection of the personal information we send around the world. A series of news reports in early 2005 concerning security breaches by companies in other countries holding personal information about Canadians has further emphasized the importance of devoting attention to transborder flows of personal information.

Research into Emerging Privacy Issues

On June 1, 2004, our Office officially launched a Contributions Program to support research by not-for-profit groups, including education institutions, industry and trade associations, and consumer, voluntary and advocacy organizations, into the protection of personal information and the ways to protect it. The program represented a milestone in the development of national privacy research capacity in Canada. The program is designed to assist our Office to foster greater public awareness and understanding of privacy.

The 2003-2004 Contributions Program had two key priorities. The first was to examine how and to what extent emerging technologies affect privacy. These included video surveillance, RFIDs, location technology and biometrics. Many of these technologies have their most profound impact on privacy when they are in the hands of government, but they often also have significant privacy implications when used by the private sector.

The second priority of the research program related more directly to the implementation of PIPEDA , especially since new sectors of the economy became subject to the Act in January 2004. This part of the Contributions Program focused on awareness and promotion of good privacy practices as a key component of responsible commercial behaviour.

The projects that were funded for a total of $371,590 include:

Funded Projects

| Canadian Marketing Association Toronto, Ontario |

Taking Privacy to the Next Level Assess and develop privacy best practices to assist businesses in better handling customer personal information under PIPEDA |

$50,000 |

|---|---|---|

|

École nationale d'administration publique (ENAP) |

Study on the use of video surveillance cameras in Canada |

$50,000 |

|

Queen's University Kingston, Ontario |

Location Technologies: Mobility, Surveillance and Privacy |

$49,972 |

|

The B.C. Freedom of Information and Privacy Association |

PIPEDA & Identify Theft: Solutions for Protecting Canadians |

$49,775 |

|

Universities of Alberta and Victoria |

Electronic Health Records and PIPEDA |

$49,600 |

|

University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario |

A review of Internet privacy statements and on-line practices |

$48,300 |

|

University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia |

Location-Based Services: An Analysis of Privacy Implications in the Canadian Context |

$27,390 |

|

Option Consommateurs Montreal, Quebec |

The challenge of consumer identification with new methods of electronic payment |

$17,100 |

|

Simon Fraser University Vancouver, British Columbia |

Privacy Rights and Prepaid Communications Services: Assessing the Anonymity Question |

$14,850 |

|

Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia |

An Analysis of Legal and Technological Privacy Implications of Radio Frequency Identification Technologies |

$14,603 |

The projects are to be completed in 2005. We will post links to the research results on our Web site.

Substantially Similar Provincial Legislation

Our Office is required by section 25(1) of PIPEDA to report annually to Parliament on the extent to which the provinces have enacted legislation that is substantially similar to PIPEDA.

Beginning on January 1, 2004, PIPEDA extended to all commercial activities. However, section 26(2)(b) allows the Governor in Council to issue an order exempting certain activities from the ambit of PIPED A. This order can be issued if the province has passed legislation that is deemed substantially similar to PIPEDA. The order can exempt an organization, a class of organizations, an activity or a class of activities from the application of PIPEDA with respect to the collection, use or disclosure of personal information subject to that legislation that occurs within the province.

The intent of this provision is to allow provinces and territories to regulate the personal information management practices of organizations within their borders while ensuring seamless and meaningful privacy protection throughout Canada.

If the Governor in Council issues an Order declaring a provincial act to be substantially similar, the collection, use or disclosure of personal information by organizations subject to the provincial act will not be covered by PIPEDA. Interprovincial and international transactions will be subject to PIPEDA, and PIPEDA will continue to apply within a province to the activities of federal works, undertakings and businesses that are under federal jurisdiction, such as banks, airlines, and broadcasting and telecommunications companies.

Process for assessing provincial and territorial legislation

On August 3, 2002, Industry Canada published a notice in the Canada Gazette Part 1 setting out how it will determine whether provincial/territorial legislation is deemed substantially similar to PIPEDA.

A province, territory or organization triggers the process by advising the Minister of Industry of legislation that they believe is substantially similar to PIPEDA. The Minister may also act on his or her own initiative and recommend to the Governor in Council that provincial or territorial legislation be found substantially similar. The notice states that the Minister will seek the Privacy Commissioner's views and include those views in the submission to the Governor in Council. The public and interested parties will also have a chance to comment.

According to the Canada Gazette notice, the Minister will expect substantially similar provincial or territorial legislation to:

- Incorporate the ten principles found in Schedule 1 of PIPEDA;

- Provide for an independent and effective oversight and redress mechanism, with powers to investigate; and

- Restrict the collection, use and disclosure of personal information to purposes that are appropriate or legitimate.

"Substantially similar" provincial legislation enacted to date

Quebec's An Act Respecting the Protection of Personal Information in the Private Sector came into effect, with a few exceptions, on January 1, 1994. The legislation sets out detailed provisions that enlarge upon and give effect to the information privacy rights contained in Articles 35 to 41 of the Civil Code of Quebec. In November 2003, the Governor in Council issued an Order in Council (P.C. 2003-1842, 19 November 2003) exempting organizations in that province, to which the provincial legislation applies. PIPEDA continues to apply to federal works, undertakings or businesses and to interprovincial and international transactions.

British Columbia and Alberta passed legislation in 2003 that applies to all organizations within the two provinces, except for (a) those covered by other provincial privacy legislation and (b) federal works, undertakings or businesses covered by PIPEDA. The two laws — both called the Personal Information Protection Act — came into force on January 1, 2004.

Using the criteria set out in the Canada Gazette notice — the presence of the ten principles found in Schedule 1 of PIPEDA , independent oversight and redress and a provision restricting collection, use and disclosure to legitimate purposes (a reasonable person test) — we concluded that the British Columbia and Alberta laws are substantially similar to PIPEDA.

For Alberta and British Columbia, the Governor in Council issued two Orders in Council (P.C. 2004-1163, 12 October 2004 and P.C. 2004-1164, 12 October 2004) exempting organizations, to which the provincial legislation applies. PIPEDA continues to apply to federal works, undertakings or businesses and to interprovincial and international transactions..

Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) came into force on November 1, 2004. PHIPA establishes rules for the collection, use and disclosure of personal health information by health information custodians in Ontario. Our Office has informed Industry Canada that we believe PHIPA as it relates to health information custodians to be substantially similar to PIPEDA. Industry Canada has requested comments on a proposed order declaring the Ontario law substantially similar to PIPEDA , but an Order in Council had not been issued when we prepared this Annual Report.

Jurisdictional Issues

For most of 2004 — beginning January 1 and ending October 12 — the Alberta and B.C. private sector privacy laws were in force, but had not yet been declared substantially similar to federal law. During this period, both the provincial private sector laws and PIPEDA applied. There was concurrent jurisdiction.

In Ontario, PIPEDA applied to personal information in the private sector (except for provincially-regulated employees) beginning on January 1, 2004. Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 ( PHIPA ) came into force on November 1, 2004. Since November 1, both PIPEDA and the Ontario legislation have applied to personal health information in the private sector. As was the case with the Alberta and B.C. private sector legislation until Ontario's PHIPA is deemed substantially similar, both PIPEDA and PHIPA will apply to personal health information in the private sector.

Even a "substantially similar" order may not be broad enough to eliminate concurrent jurisdiction completely. With Ontario, for example, the "substantially similar" order will not apply to some entities regulated by Ontario's PHIPA. The proposed order may apply in respect of the rules governing health information custodians; Ontario's PHIPA would therefore be the sole law applying to health information custodians' collection, use, or disclosure of personal information in Ontario.

But the substantially similar order would not apply to third parties who receive personal information from health information custodians. PHIPA imposes rules on non-health information custodians only about the use and disclosure of personal health information. PHIPA does not regulate other privacy obligations, such as collection, access and safeguards. Therefore, PIPEDA would continue to apply to these activities.

One simple way to avoid the work of Commissioners overlapping in areas of concurrent jurisdiction is to reach informal agreements about who handles what. Our Office will work closely with Ontario, as it has with B.C. and Alberta, to ensure that both Acts are enforced in the most seamless way possible.

Even where a "substantially similar" order exists, not all intraprovincial commercial activity will necessarily be covered by the order, and jurisdictional boundaries are not always clear. Complex jurisdictional issues may still arise and require close collaboration between jurisdictions to deal with them.

For instance, Alberta's Health Information Act ( HIA ) applies to health service providers who are paid under the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan to provide health services. On this definition, HIA does not cover health practitioners, who provide health services privately. While Alberta's Personal Information Protection Act ( PIPA ) does apply to private sector organizations, it does not apply to health information, as defined by HIA, which is collected, used or disclosed for health care purposes. Under this regime, the collection, use or disclosure of personal health information by practitioners working in private practice to provide health services seems to have fallen between the cracks; it is not currently covered by either Alberta Act. Hence, such activity is subject to the federal PIPEDA.

As a postscript, a bill was introduced in the Legislative Assembly of Alberta in March 2005 to amend Alberta's PIPA in favour of bringing the activities of private practitioners who collect, use or disclose personal health information in the course of providing health services clearly within the scope of PIPA. This amendment has since come into force and resolved this jurisdictional problem.

Flows of personal information across provincial boundaries

Another aspect of the jurisdictional issue arises with flows of information across provincial boundaries. An Alberta company may disclose personal information to another company in Saskatchewan in the course of a commercial activity. An individual could complain about this interprovincial transaction to our Office. Alternatively, an individual who wants to complain about the disclosure of personal information by the Alberta company could direct the complaint to the Alberta Information and Privacy Commissioner under Alberta's PIPA. However, if the individual is complaining about the collection in Saskatchewan of their personal information, he or she may direct the complaint to the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, as Saskatchewan does not have substantially similar legislation in place governing its private sector organizations' activities. Whether the complaint is initiated in Alberta, with our Office, or both, our respective offices will work together to coordinate our work where possible.

Sometimes the jurisdictional issue is entangled. In one case handled by our Office, the complainant worked for an organization in one of the western provinces that has substantially similar legislation. The organization provides disability insurance. The individual applied to the insurance company, located in Quebec, for access to her files. Those files are kept in Toronto. The insurance company responded as if PIPEDA regulated the question. Is PIPEDA the appropriate legislation or does it fall to one of the provinces?

In another case, an individual worked for a company in one of the western provinces with substantially similar legislation. Through the company, the individual had an employee assistance program (EAP) in Ontario, and complained about a disclosure by the EAP. Because Ontario does not yet have substantially similar legislation, PIPEDA would apply in Ontario. But is this an Ontario issue — because the EAP is located in Ontario — or is it within the jurisdiction of the western province under that province's private sector legislation?

Streamlining our approach to jurisdictional issues

Federal and provincial Commissioners are working together to resolve jurisdictional challenges. This process has been collegial, not confrontational. Some individuals may raise jurisdictional matters in the courts but these issues can largely be resolved through discussion. Our goal in every case is to establish as simple and clear a mechanism as possible for individuals and organizations.

One way we have sought to streamline our approach to jurisdictional and related investigative issues is to establish a regional private sector privacy forum with Alberta and British Columbia. This forum operates under the authority of the federal and provincial Commissioners and seeks to coordinate and harmonize federal and provincial oversight of the private sector in Canada. Senior investigations and legal staff from each of the Commissioners' offices take part in monthly teleconferences and twice-yearly meetings. The forum serves many functions, but among the most important is to develop procedures for determining jurisdiction, transferring complaints and conducting parallel investigations.

Federal and provincial Commissioners have also been working to develop protocols for handling investigations where there may be overlapping jurisdiction. In March 2004, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada sent a letter of understanding to the Information and Privacy Commissioners of Alberta, British Columbia, and a similar letter to the Ontario Information and Privacy Commissioner in January 2005, to confirm discussions about the handling of complaints relating to organizations in those provinces. In part, these letters of understanding set out how our Office would handle complaints both before and after a finding of "substantially similar" occurs in respect of the provincial laws.

These letters of understanding are available on the Privacy Commissioner of Canada's Web site (www.priv.gc.ca). There is further information about jurisdictional issues, including a fact sheet, on our Web site, as well as on the Web sites of other provincial Information and Privacy Commissioners.

Our Office has had a long-standing relationship with the Commission d'accès à l'information (CAI) in Quebec. Quebec was the first Canadian jurisdiction to adopt private sector privacy legislation in 1994. In order to take advantage of the rich body of jurisprudence accumulated in Quebec since 1994, we have commissioned a document to review and summarize Quebec's experience to date.

In order to ensure that this may be as helpful as possible to all jurisdictions, we established an External Editorial Board to assist in the project. The members are:

Madeleine Aubé, General Counsel, Commission d'accès à l'information du Québec

Jeffrey Kaufman, Fasken Martineau, Toronto

Mary O'Donoghue, Senior Counsel, Ontario Information and Privacy Commissioner's Office

Murray Rankin, Arvay Finlay, Victoria

Frank Work, Q.C., Information and Privacy Commissioner of Alberta

This document was published in August 2005 and is available on our Web site.

The Alberta and federal Commissioners have already cooperated in investigating issues that have both federal and provincial elements — see for example, the case summary relating to a joint federal/provincial investigation of misdirected medical information mentioned below in the section on Incidents under PIPEDA. In another case, Edmonton police conducting an investigation found information used in determining security clearances for Alberta government employees. The information included credit reports. The aspects of the investigation relating to correction of erroneous credit reports fell to the Alberta Information and Privacy Commissioner, while our Office handled the systemic issue of retention of credit reports.

While the constitutional pitfalls may be numerous, we hope a practical approach to the application of the way personal information protection legislation in Canada will yield, overall, effective privacy protection in Canada.

Evolution of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

Statutory Changes

PIPEDA Amendments

The Public Safety Act, 2002Footnote 1 included two amendments to PIPEDA. Their effect is to permit organizations to collect and use personal information without consent for the purposes of disclosing this information when required by law or to government institutions if the information relates to national security, the defence of Canada or the conduct of international affairs.

The Commissioner appeared before the Senate Standing Committee on Transport and Communications on March 18, 2004, to voice her concerns about these amendments.Footnote 2 In her statement to the Committee, the Commissioner pointed out that the amendments will allow organizations to act as agents of the state by collecting information without consent for the sole purpose of disclosing it to government and law enforcement agencies. She asked that the changes to PIPEDA be dropped, and expressed concern that the wording of these changes was so broad that they could apply to any organization subject to PIPEDA, with no limit on the amount of information to be collected or the sources of the information.

The Public Safety Act, 2002, without the changes recommended by the Commissioner, came into force on May 11, 2004.

Amendments to Other Acts

The Federal Court Rules, 1998 were enacted before PIPEDA. Because of this, rule 304(1)(c), which deals with service of a "notice of application", had no reference to PIPEDA. Accordingly, in February 2003 our Office's Legal Branch requested an amendment to rule 304(1)(c) to include notifying the Privacy Commissioner whenever an application is filed under PIPEDA, as well as when one is filed under the Privacy Act.

The Rules Amending the Federal Court Rules, 1998 came into force on November 29, 2004 and were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II of December 15, 2004 as SOR/2004-283. Section 16 of this document amended rule 304(1)(c) to include PIPEDA so that the text of that section now reads:

[...] 304(1)(c) where the application is made under the Access to Information Act , Part 1 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, the Privacy Act or the Official Languages Act, the Commissioner named for the purposes of that Act; and [...]

2006 Review of PIPEDA by Parliament

The Office has been preparing for the upcoming review of PIPEDA by Parliament, scheduled to take place in 2006. The year 2006 may appear a long way off from the vantage point of this 2004 Annual Report, but our experience over the past four years in overseeing the application of the law has convinced us that this a good time to begin preparing, and that our Office is also the right place to begin. This Office will be active in developing policy positions to make the operation of the law simpler and more effective for organizations and individuals alike, and to ensure that the fair information practices at the heart of PIPEDA are translated into practice.

Like any significant new law, PIPEDA has its problems. It is hard to get the first version of any law completely "right", particularly when it is breaking new ground and providing new rights and obligations. We don't have all the solutions for these problems, but we have identified several issues and, in some cases, suggested possible ways to address them.

- Scope

- Does PIPEDA deal effectively with employee information? Many of our complaints arise in the context of the employer/employee relationship. The current PIPEDA doesn't always fit that relationship. Both the B.C. and Alberta private sector legislation deal with employee information under a separate set of rules.

- There are clear overlaps between PIPEDA and the Canada Labour Code and between the mandate of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner and that of labour arbitrators.

- There remains uncertainty about the distinction, if there is one, between "commercial" activity, as defined in the Act, and "professional" services.

- Elsewhere in this report, we describe a case that involved sending unsolicited commercial e-mail to a business e-mail address. The legislated definition of "personal information" excludes certain business information such as address and phone number. Should business e-mail addresses also be excluded?

- Consent

- Consent is at the heart of PIPEDA. It is also one of the most problematic issues under the Act. For example, must an organization obtain the consent of all its customers when it proposes to disclose their information in the context of a business merger or acquisition? That seems to be what the law requires, but it is not always practicable for several sound business reasons. The B.C. and Alberta private sector laws both deal with this issue head-on and establish rules to protect customer information in these circumstances. Should PIPEDA do the same?

- Oversight

- PIPEDA gives the Commissioner the powers of an ombudsman — in other words, no power to issue an order or levy a penalty against an organization violating PIPEDA. While we think that the ombudsman model works well overall (in fact, even in jurisdictions that have order-making powers on privacy matters, the vast majority of cases are settled without an order) we are aware that oversight bodies in other jurisdictions have enforcement powers. Parliament may want to consider the advantages and disadvantages of both models in its 2006 review of PIPEDA.

These are simply a few of the issues that may need to be addressed in the five year review of the Act.

Complaints

In 2004, PIPEDA reached its full extension, to cover all commercial activities in provinces without substantially similar legislation. Over the year, we saw a significant spike in complaints filed under PIPEDA : we received 723 complaints between January 1 and December 31, more than double the 302 received in the previous calendar year. The expansion of the Act's coverage appears to be a considerable factor in the increase. Financial institutions were once again the most frequent object of complaints, as one might expect given the vast quantities of personal information that pass through their hands. They were followed by the telecommunications sector, also a front-runner in years past. But complaints in four areas new to us — insurance, sales, accommodation, and professionals — accounted between them for over 25 per cent of the complaints. It remains to be seen whether we will see further increases, as the Act becomes better known to Canadians.

PIPEDA complaints received between January 1 and December 31, 2004

Sectoral Breakdown

| Sector | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Institutions | 212 | 29.3% |

| Telecommunications | 125 | 17.3% |

| Insurance | 82 | 11.3% |

| Sales | 82 | 11.3% |

| Transportation | 67 | 9.3% |

| Health | 36 | 5% |

| Accommodation | 18 | 2.5% |

| Professionals | 15 | 2.1% |

| Services | 10 | 1.4% |

| Other | 76 | 10.5% |

| Total | 723 | 100% |

The complaints related to the following concerns:

Breakdown by Complaint Type

| Complaint type | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Use and Disclosure | 286 | 39.6% |

| Collection | 172 | 23.8% |

| Access | 112 | 15.5% |

| Safeguards | 40 | 5.5% |

| Consent | 37 | 5.1% |

| Accuracy | 22 | 3% |

| Correction/Notation | 11 | 1.5% |

| Fee | 12 | 1.7% |

| Other | 4 | 0.6% |

| Retention | 6 | 0.8% |

| Accountability | 9 | 1.2% |

| Time Limits | 9 | 1.2% |

| Challenging Compliance | 1 | 0.2% |

| Openness | 2 | 0.3% |

| Total | 723 | 100% |

During the year, we closed 379 complaints. This is an improvement over the previous year, where we closed 278. Nonetheless, in both years we received more complaints than we closed. This presents the Office with the risk of a developing backlog.

We are taking initiatives to address this, including reallocating resources and reviewing the way in which we conduct our investigations. One of the most promising approaches may be a new emphasis, since January 2004, on a category of complaint disposition, "Settled during the course of the investigation." These are cases in which, during the investigation, we have helped bring about a solution satisfactory to all parties.

Complaint Investigations Treatment Times — PIPEDA

This table represents the average number of months it has taken to complete a complaint investigation by disposition, from the date the complaint is received to when a finding is made.

By Disposition

For the period between January 1 and December 31, 2004.

| Disposition | Average Treatment Time in Months |

|---|---|

| Early Resolution | 2.9 |

| Discontinued | 5.6 |

| Settled | 7.2 |

| No jurisdiction | 7.8 |

| Resolved | 10.5 |

|

Not well-founded |

11.0 |

|

Well-Founded |

11.0 |

| Overall Average | 8.3 |

By Complaint Type

For the period between January 1 and December 31, 2004.

| Complaint Type | Average Treatment Time in Months |

|---|---|

| Fee | 3.4 |

| Accuracy | 6.4 |

| Consent | 6.9 |

| Time Limits | 8.1 |

| Use and Disclosure | 8.2 |

| Access | 8.3 |

| Safeguards | 8.4 |

| Correction/Notation | 8.5 |

| Collection | 8.9 |

| Retention | 9.5 |

| Accountability | 12.0* |

| Challenging compliance | 12.0* |

| Overall average | 8.3 |

* The average treatment times for these two complaint types in fact represent one case for each.

Settling complaints in investigation is not new, but our emphasis on it is. In 2003, settled cases represented two per cent of our completed cases. In contrast, of the 379 cases concluded in 2004, 152 — just over 40 per cent — fell in the "settled" category. This was by far the most frequent disposition of our cases.

This new emphasis on settlement is an important element in dealing with the volume of complaints that we face. Over the course of the year, settlement of a complaint took, on average, less time than any other complaint resolution except discontinuance (where, for instance, the complainant may no longer want to pursue the matter or cannot be located) or early resolution, where the issue is dealt with before any investigation takes place.

If we take the figures for the "settled" and "early resolution" categories, we can see that 45 per cent of our complaints are concluded without the investment of resources entailed in a complete investigation. This is welcome news to an organization facing an increasing workload.

That we were able to settle so many of our cases suggests that organizations and individual complainants welcome the opportunity to resolve complaints expeditiously and pragmatically. This fits well with our ombudsman role; we are in this business, after all, to help people resolve problems. At the same time, of course, we have a responsibility to ensure that the public policy intentions of PIPEDA are respected. Our Office, as much as the complainant and the organization, has an interest in any settlement; our view, however, is that enthusiasm for settlement does not mean settling complaints at any cost. Our investigators work closely with the parties in the settlement process to ensure that systemic issues raised in a complaint are addressed.

Complaints closed between January 1 and December 31, 2004: Type of Conclusion

Definitions of Complaint Types under PIPEDA

Complaints received in the Office are categorized according to the principles and provisions of PIPEDA that are alleged to have been contravened:

- Access. An individual has been denied access to his or her personal information by an organization, or has not received all his or her personal information, either because some documents or information are missing or the organization has applied exemptions to withhold information.

- Accountability. An organization has failed to exercise responsibility for personal information in its possession or custody, or failed to identify an individual responsible for overseeing its compliance with the Act.

- Accuracy. An organization has failed to ensure that the personal information that it uses is accurate, complete, and up-to-date.

- Challenging compliance. An organization has failed to put procedures or policies in place that allow an individual to challenge its compliance with the Act, or has failed to follow its own procedures and policies.

- Collection. An organization has collected personal information that is not necessary, or has collected it by unfair or unlawful means.

- Consent. An organization has collected, used, or disclosed personal information without valid consent, or has made the provision of a good or service conditional on individuals consenting to an unreasonable collection, use, or disclosure.

- Correction/Notation. The organization has failed to correct personal information as requested by an individual, or, where it disagrees with the requested correction, has not placed a notation on the information indicating the substance of the disagreement.

- Fee. An organization has required more than a minimal fee for providing individuals with access to their personal information.

- Retention. Personal information is retained longer than necessary for the fulfillment of the purposes that an organization stated when it collected the information, or, if it has been used to make a decision about an individual, has not been retained long enough to allow the individual access to the information.

- Safeguards. An organization has failed to protect personal information with appropriate security safeguards.

- Time Limits. An organization has failed to provide an individual with access to his or her personal information within the time limits set out in the Act.

- Use and Disclosure. Personal information is used or disclosed for purposes other than those for which it was collected, without the consent of the individual, and the use or disclosure without consent is not one of the permitted exceptions in the Act.

Investigation Process under the PIPEDA

Definitions of Findings under PIPEDA

The Office has developed a series of definitions of "findings" to explain the outcome of its investigations under PIPEDA:

Not well-founded: This means that the investigation uncovered no or insufficient evidence to conclude that an organization violated the complainant's rights under PIPEDA.

Well-founded: This means that an organization failed to respect a provision of PIPEDA.

Resolved: This means that the investigation substantiates the allegations, but that the organization has taken or has committed to take corrective action to remedy the situation, to the satisfaction of our Office.

Settled during the course of the investigation: This means that the Office has helped negotiate a solution that satisfies all involved parties during the course of the investigation. No finding is issued.

Discontinued: This means that the investigation ended before a full investigation of all the allegations. A case may be discontinued for any number of reasons — for instance, the complainant may no longer want to pursue the matter or cannot be located to provide information critical to making a finding.

No jurisdiction: This means that the investigation leads to a conclusion that PIPEDA does not apply to the organization or to the activity that is the subject of the complaint.

Early resolution: This is a new type of disposition. It applies to situations where the issue is dealt with before a formal investigation occurs. For example, if an individual files a complaint about a type of issue that the Office has already investigated and found to comply with PIPEDA, we would explain this to the individual. "Early resolution" would also apply when an organization, on learning of allegations against it, addresses them immediately to the satisfaction of the complainant and this Office.

Findings by Complaint Type

Complaints closed between January 1 and December 31, 2004

| Discontinued | Early Resolution |

No Jurisdiction |

Not well-founded |

Resolved | Settled | Well-founded | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | 10 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 20 | 14 | 62 (16%) |

| Accountability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0%) |

| Accuracy | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 (1%) |

| Challenging Compliance |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0%) |

| Collection | 10 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 15 | 30 | 13 | 96 (25%) |

| Consent | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 7 (2%) |

| Correction/ Notation |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (1%) |

| Fee | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 (1%) |

| Retention | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (1%) |

| Safeguards | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 18 (5%) |

| Time Limits | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 (2%) |

| Use and Disclosure | 22 | 10 | 1 | 25 | 5 | 77 | 33 | 173 (46%) |

| Total (# and %) |

46 (12%) |

19 (5%) |

6 (2%) |

63 (17%) |

27 (7%) |

152 (40%) |

66 (17%) |

379 |

Inquiries

The Inquiries Unit responds to requests for information from the public about the application of PIPEDA as well as the Privacy Act. The Office receives thousands of inquiries each year from the public and organizations seeking advice on private sector privacy issues.

In 2004, the Office received 12,132 PIPEDA inquiries, down from 2003, when we received 13,422. The decline may be attributable to greater understanding of PIPEDA among the organizations that are subject to it; in 2003, many organizations were searching for guidance as they anticipated the full implementation of PIPEDA on January 1, 2004.

In the course of the year, staff shortages in the Inquiries Unit coupled with the ongoing heavy volume of work have presented challenges. As a result, it was necessary to reassess the way we respond to public inquiries. We no longer accept or respond to inquiries or complaints by e-mail. We introduced an automated telephone system to answer the public's most frequently asked questions such as those about identity theft, telemarketing and, of course, the social insurance number. And we continue adding information to our Web site to answer the most frequently asked questions. We also temporarily assigned some investigators to help the unit. Lastly, we now invite individuals to telephone during office hours since we can often determine a caller's needs faster and better in person than in a series of e-mails and letters.

Inquiries Statistics

January 1 to December 31, 2004

The following table represents the total number of PIPEDA inquiries responded by the Inquiries Unit.

| Telephone inquiries | 8,861 |

|---|---|

| Written inquiries (letter, e-mail and fax) | 3,271 |

| Total number of inquiries received | 12,132 |

Inquiries Response Times

On average, written inquiries (one quarter of the workload of the Unit) were responded to within three months. Nearly 3/4 of our inquires were received by telephone. The majority of these were responded to immediately; the remainder, which may have required research, were responded to within one to two weeks.

Providing written responses to inquiries is very time consuming and labour intensive. Over the year, the Inquiries Unit accrued a backlog of inquiries which exacerbated the average monthly response times. As we implement new measures, we will monitor the situation to determine whether these changes have resulted in efficiency gains.

Select Cases under PIPEDA

The following cases illustrate the breadth and variety of the cases investigated by our Office. We also posted 29 summaries of findings for 2004 on our Web site.

Medical information divulged through indiscreet choice of words

Even with the best of intentions, and even in such seemingly harmless activities as arranging for a taxi, health professionals must watch what they say to company managers about employees' health situations.

The facts

After completing a substance abuse program, a complainant signed a "last chance" contract as a condition of continued employment with a national transportation company. This contract required him to submit to regular monitoring, as well as random drug and alcohol testing, by the company's health service provider. The complainant was very concerned about confidentiality and for the most part had managed to keep his situation from fellow employees and supervisors.

One day while he was at home on active furlough, he received a call from a nurse, who told him he had to be at the clinic within four hours to give a urine sample. When he told the nurse he had no way of getting there, she said she would call the company and arrange for a taxi. The complainant soon got a call from his supervisor, who told him a taxi would take him "to the lab". The supervisor then asked him whether he was "under contract" — meaning a last-chance contract.

From the supervisor's words, the complainant assumed that the nurse had revealed too much information about him. Angered by what he believed to be a breach of his confidentiality, he later confronted both the nurse and the supervisor in abusive language that the company deemed to be grounds for disciplinary action. An investigation ensued, and the complainant was eventually dismissed for conduct unbecoming an employee (he has since been reinstated).

The supervisor told our Office that he had assumed the complainant's involvement in the substance abuse monitoring program from the nurse's use of the words "test" and "clinic" in his telephone conversation with her. The nurse, on the other hand, told us that she had used the word "appointment", not "test". She claimed to have given the supervisor only the minimum information necessary to make it clear that a taxi was needed and that there was a reasonable basis for the company to pay for it.

At one point, the company's regional superintendent had asked the nurse to document her version of the events relating to the complainant's alleged misconduct. She did so in an e-mail, which was sent to the regional superintendent and later forwarded to two other senior managers. In the e-mail, the nurse stated that the complainant had been required to undergo a "medical test ... to assure his continuing fitness for duty" and that he had had to take the test within four hours after her phone call to him. Believing that this information implied his participation in the program, the complainant objected that it had been conveyed to the parties in question.

The complainant's allegation to our Office was that the nurse had inappropriately divulged his personal information to his supervisor in a telephone conversation and to other senior managers in an e-mail message.

Our findings

With respect to the telephone conversation, though it seemed appropriate that the nurse would have had to provide the supervisor with a reason to justify the taxi request, our investigation could not establish what exactly she had said to the supervisor. Whatever wording she used, it either caused the supervisor to conclude, or confirmed his suspicion, that the complainant was in the substance abuse monitoring program.

Similarly with respect to the e-mail, we did not dispute the need to inform senior managers of the complainant's alleged misconduct, but the problem was the information's content. Since the nurse's purpose had been to document the complainant's behaviour, stating that he had been required to go for a medical test within four hours was superfluous. The words "medical appointment" would have been sufficient to explain the need for a taxi.

The company was therefore found to have inappropriately used the complainant's personal information in contravention of Principle 4.3 of the Act. The complaint was well-founded.

Professor objects to getting spammed at the office

Is a person's business e-mail address fair game for marketers?

The facts

At his university office, a complainant received an unsolicited commercial e-mail promoting season's tickets for a professional team's games. The sales agent in question admitted to having obtained the e-mail address from the university's Web site, and he agreed not to send the complainant further e-mails without his consent. Two weeks later, however, the complainant received a second e-mail solicitation from the same organization, but a different sales agent.

The complainant's allegation to our Office was that the organization had collected and used his personal information without his consent.

The organization did not dispute that it had sent the complainant a solicitation at his office e-mail address on two occasions. The two sales representatives in question were each responsible for a different solicitation "program" — one the "university program", and the other the "lawyer program". The agent responsible for the lawyer program had generated his contact list from the Web site of a law firm with which the complainant was associated. There was no cross-referencing system in place to flag the complainant's previous request that his name be deleted from the organization's marketing lists.

In response to the complaint, the organization removed the complainant's name from all its marketing lists and instituted cross-selling controls to ensure similar treatment of any future objection. The organization has also engaged a new ticketing and sales firm that is more knowledgeable about the requirements of PIPEDA.

The view of the university in question is that the e-mail addresses of its staff are business information. The university generally requires its faculty members to agree to have their business e-mail addresses published, in accordance with its business model and its expectation that employees be easily accessible. However, the university also expects a business or organization to obtain permission before contacting faculty for purposes unrelated to promoting the university's interests.

Section 2 of the Act specifically excludes the name, title, or business address or phone number of an employee of an organization from the definition of personal information, but makes no mention of an employee's business e-mail address. Sections 7(1)(d) and 7(2)(c.1) stipulate that an organization may collect and use personal information without the individual's knowledge and consent if the information is publicly available and specified in the regulations.

The regulations applying to these sections state that publicly available information includes an individual's name, title, address, and telephone number appearing in a professional or business directory, listing, or notice that is available to the public, where the collection, use, and disclosure of the personal information relate directly to the purpose for which the information appears.

Our findings

We determined first that, since section 2 does not specify a business e-mail address as being among the excluded types of information, it must therefore be deemed personal information for purposes of the Act.

The question then to be considered was whether the sports organization could rely on the exceptions to consent set out in sections 7(1)(d) and 7(2)(c.1).