Submission of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020

May 2021

VIA EMAIL

May 11, 2021

Mr. Chris Warkentin, M.P.

Chair, Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics

Sixth Floor, 131 Queen Street

House of Commons

Ottawa ON K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Chair:

Subject: Submission on C-11

Further to my appearance before you on May 10, 2021, please find enclosed our submission on Bill C-11, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020. I hope these materials will assist your deliberations on this important piece of privacy legislation.

As I indicated when I appeared before you in the context of the Main Estimates and your study of Facial Recognition Technology, I believe that C-11 represents a step back overall from our current law and needs significant changes if confidence in the digital economy is to be restored. My submission outlines numerous enhancements that are required to help ensure that organizations can responsibly innovate in a manner that recognizes and protects the privacy rights of Canadians.

My opening message provides an overview of our position, while the rest of the document contains a detailed analysis of the bill and recommendations that we believe are necessary.

I am also including an analysis paper prepared for my Office by Dr. Teresa Scassa on the problems with how Bill C-11 would address the issue of trans-border transfers of personal information. It identifies key provisions of C-11 that relate to trans-border data transfers, critically analyzes the extent to which these provisions would substantively protect privacy and offers a series of recommendations for improvement.

I hope these materials will be useful for the Committee. I remain available to meet with Parliament on this important Bill at its convenience.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Commissioner

encl. (1)

c.c.: The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry

Ms. Miriam Burke

Clerk of the Committee

Commissioner’s message

Bill C-11, which enacts the Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) and the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act (PIDPTA), is an important and concrete step toward privacy law reform in Canada. Arising from the 2019 Digital Charter, and following years of Parliamentary studies, Bill C-11 represents a serious effort to realize the reform that virtually all – from Parliamentarians, to industry, privacy advocates, and everyday Canadians – have recognized is badly needed. It was an ambitious endeavour to completely restructure the existing Act. We are pleased to see that the law reform process appears to be truly underway.

The Bill completely rewrites that law and seeks to address several of the privacy concerns that arise in a modern digital economy. It promises more control for individuals, much heavier penalties for organizations that violate privacy, while offering companies a legal environment in which they can innovate and prosper.

We agree that a modern law should both achieve better privacy protection and encourage responsible economic activity, which, in a digital age, relies on the collection and analysis of personal information. However, despite its ambitious goals, our view is that in its current state, the Bill would represent a step back overall for privacy protection. This outcome can be reversed, and the Bill could become a strong piece of legislation that effectively protects the privacy rights of Canadians, with a number of important amendments under three themes:

- a better articulation of the weight of privacy rights and commercial interests;

- specific rights and obligations;

- access to quick and effective remedies and the role of the OPC.

Why do I say that the Bill as drafted would represent a step back? In general terms, because the Bill, although seeking to address most of the privacy issues relevant in a modern digital economy, does so in ways that are frequently misaligned and less protective than laws of other jurisdictions. Our recommendations would lead to greater alignment.

More specifically, I say the Bill as drafted would be a step back overall because the provisions meant to give individuals more control give them less; because the increased flexibility given to organizations to use personal information without consent do not come with the additional accountability one would expect; because administrative penalties will not apply to the most frequent and important violations, those relevant to consent and exceptions to consent; and because my Office would not have the tools required to manage its workload to prioritize activities that are most effective in protecting Canadians. In fact, the OPC would work under a system of checks and balances (including a new administrative appeal) that would unnecessarily stand in the way of quick and effective remedies for consumers.

Poll after poll suggest there is currently a trust deficit in the digital economy. Improving trust is one of the objectives of the Digital Charter that Bill C-11 seeks to implement. After years of self-regulation, or permissive regulation, polls also suggest this requires more regulation (objective and knowable standards adopted democratically) and oversight (application of these standards by democratically appointed institutions). The regulation required is sensible legislation that allows responsible innovation that serves the public interest and is likely to foster trust, but that prohibits using technology in ways that are incompatible with our rights and values.

Oddly, the government’s narrative in presenting the Bill, while positive in many respects, focused on the need for “certainty” and “flexibility” for businesses and the need for “checks and balances” on the regulator. Unfortunately, it appears this was not a slip of the tongue, as we see that philosophy reflected in several provisions of the Bill.

The OPC welcomes transparency and accountability for its actions, and we agree businesses need some level of certainty and flexibility, within the law. But the focus on checks and balances for the regulator and more certainty and greater flexibility for businesses seems misplaced. It leads to the flaws identified earlier and to an imbalance in the law on the importance of rights and commercial interests.

Better articulation of the weight of rights and commercial interests

Digital technologies are at the heart of the fourth industrial revolution and modern economies. As we have seen in the current pandemic, they can serve the public interest. This includes economic prosperity.

For both good and bad, these technologies are disruptive. They have been shown to pose major risks for privacy and other rights. Data breaches have become routine. There is increasing talk of surveillance capitalism – this, a few years after the Snowden revelations of state surveillance. Biometrics heightens those risks. More recently, the Cambridge Analytica scandal highlighted the risks for democracy. Artificial intelligence brings risks to equality rights. And on and on.

Ultimately, it is up to parliamentarians, as elected representatives of the population, to decide how much weight to give to privacy rights and the interests of commercial enterprises.

My Office has argued for a modernization of laws that would give organizations greater flexibility to use personal information without consent for responsible innovation and socially beneficial purposes, but within a legal framework that would entrench privacy as a human right and as an essential element for the exercise of other fundamental rights.

The Bill maintains that privacy and commercial interests are competing interests that must be balanced. In fact, the Bill arguably gives more weight to commercial interests than the current law by adding new commercial factors to be considered in the balance, without adding any reference to the lessons of the past twenty years on technology’s disruption of rights.

The courts have held that PIPEDA’s purpose clause, without the new commercial factors added in Bill C-11, means privacy rights must be “reconciled” with commercial interests. This is a reasonable interpretation of the direction given to courts and the regulator by Parliament when it enacted PIPEDA in 2000.

Parliamentarians now have a chance to confirm or amend this direction. There is no dispute that the CPPA should both promote rights and commercial interests. The question is what weight to give to each.

In my view, it would be normal and fair for commercial activities to be permitted within a rights framework, rather than placing rights and commercial interests on the same footing. Generally, it is possible to concurrently achieve both commercial objectives and privacy protection. However, when there is a conflict, I believe rights should prevail. The recent Clearview matter is a good example of that principle.

To adopt a rights-based approach would also send a powerful message as to who we are and what we aspire to be as a country. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is an integral part of our character and Canada is a signatory to international instruments that recognize privacy as a human right. We are a bijural country, in which the common law and civil law systems coexist in harmony. In Quebec, existing privacy laws seek to implement the right to privacy protected in the Civil Code and the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. Bill 64 would further protect privacy as a human right. Adopting a rights-based approach in the CPPA, including some elements of Bill 64’s provisions, would reflect Canada’s bijural nature.

Canada also aspires to be a global leader in privacy and it has a rich tradition of mediating differences on the world stage. Adopting a rights-based approach, while maintaining the principles-based and not overly prescriptive approach of our private sector privacy law, would situate Canada as a leader showing the way in defining privacy laws that reflect various approaches and are interoperable.

Our detailed submissions comment further on this and include a new preamble and amendments to sections 5, 12 and 13 of the proposed CPPA.

Specific rights and obligations

Again, I refer you to our detailed submissions for a fuller analysis of this theme. Let me now focus on consent, exceptions thereto and accountability.

(i) Valid vs meaningful consent

The Bill seeks to give consumers more control over their personal information. It does this by prescribing elements that must appear in a privacy notice, in plain language. This is similar to the approach taken in our 2018 Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent, with an important omission. Bill C-11 also makes the same omission of a crucial aspect of meaningful consent under the current law (s. 6.1 of PIPEDA): “the consent of an individual is only valid if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting.” (my emphasis)

By prescribing elements of information to appear in privacy notices without maintaining the requirement that consumers must be likely to understand what they are asked to consent to, the CPPA would give individuals less control, not more.

This is exacerbated by the open-ended nature of the purposes for which organizations may seek consent. PIPEDA currently requires that purposes be “explicitly specified” and be legitimate. This is consistent with the laws of most other jurisdictions, which prescribe that purposes must be defined “explicitly”, or even “as explicitly as possible”. This limitation, which is important for consumers to understand what they are consenting to, is also omitted from Bill C-11. With the result that, conceivably, organizations could seek consent for vague and mysterious purposes, such as “improving your consumer experience”.

Finally on this point, while s. 15(4) of the CPPA would make express consent the rule, this provision would allow an organization to rely on implied consent where it “establishes” (in French, “conclure” or concludes) that this would be appropriate, in light of certain factors. Bill C-11 therefore seems to give deference to an organization’s conclusion that implied consent is appropriate, as opposed to prescribing an objective assessment of the relevant factors. This is another manifestation of the philosophy where businesses would be given certainty and flexibility, rather than be subject to objective standards and oversight. A simple amendment, striking the words “the organization establishes that” in s. 15(4), would solve the problem and would fully implement the recommendation made by the ETHI Committee in 2018.Footnote 1

(ii) Exceptions to consent and accountability

The CPPA would add important new exceptions to consent. We think this is appropriate in a modern privacy law.

Among the lessons of the past twenty years is that privacy protection cannot hinge on consent alone. Simply put, it is neither realistic nor reasonable to ask individuals to consent to all possible uses of their data in today’s complex information economy. The power dynamic is too uneven.

In fact, consent can be used to legitimize uses that, objectively, are completely unreasonable and contrary to our rights and values. In these circumstances, consent rules do not protect privacy but contribute to its violation. This also leads to the trust deficit affecting the digital economy.

Several of the new exceptions to consent brought by Bill C-11 are reasonable. We have two main concerns: some exceptions are unreasonably broad; and the Bill fails to associate greater authority to use personal information with greater accountability by organizations for how they rely on these broader permissions.

Paragraphs 18(2)(b) and (e) of the CPPA are too broad. The first can likely be narrowed but the second should be repealed. We can find no reasonable justification for an exception to consent based on the impracticability of obtaining consent. This would make the rule (consent) completely hollow. There may be some specific activities (for instance those of search engines) that should be permitted for the usefulness of their service even though consent may be impracticable. Or, as recommended in our recent paper on artificial intelligence, the CPPA could include a consent exception for “legitimate business purposes”, but only within a rights-based privacy law.

With Bill C-11, organizations would have much wider permission to collect, use and disclose the personal information of consumers, without consent. Or, put differently, the Bill recognizes that consent is often a fiction and tries to find ways to allow but regulate modern business operations that “(rely) on the analysis, circulation and exchange of personal information” (s. 5), where consent is neither reasonable nor realistic.

Creating newer and broader exceptions to consent means that the law would place less weight on individual control as a means to protect privacy. This form of protection should be replaced by others. Greater permission to use data should come with greater accountability for organizations. There is a consensus on this point in the privacy community, even among industry representatives.

Yet the CPPA would not enhance PIPEDA’s principle of accountability. It would arguably weaken it. In part by defining accountability in descriptive rather than normative terms. Accountability would not be, as in other laws and the OPC guidelines, translated in policies and procedures that ensure (normative goal) compliance with the law, but rather as those policies and procedures that an organization decides to put in place (descriptive) to fulfil its obligations. Again, certainty and flexibility for businesses, rather than standards and oversight.

We have argued for some time that in the current digital economy, based on complex technologies and business models which are difficult if not impossible to understand for consumers, the OPC as expert regulator should have the authority to proactively inspect, audit or investigate business practices to verify compliance with the law, without prior evidence or grounds that the law has been violated. This ability to “look under the hood” of these complex technologies and business models, not arbitrarily but based on our expert assessment of privacy risks, and subject to judicial review, is in our view a necessary element of a modern privacy law.

These provisions exist in the privacy laws of Quebec and Alberta and in those of several foreign jurisdictions, including common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Ireland, and is proposed by the Department of Justice in its latest consultation paper on Privacy Act reform. They would ensure that organizations are held accountable for the way in which they use the increased flexibility to collect, use and disclose the personal information of consumers. For instance, they would ensure that automated decision-making systems and artificial intelligence are developed and applied in a privacy compliant manner. They would also help address the concerns of Canadians that underlie the deficit of trust in the digital economy.

Finally, the CPPA’s provisions on accountability should explicitly include a requirement that organizations apply Privacy by Design, as recommended in ETHI’s 2018 report, and that privacy impact assessments (PIAs) be prepared for higher risk activities. Requiring PIAs for all activities involving personal information would create an excessive burden on organizations, particularly SMEs. But Privacy by Design and PIAs are important for their proactivity in protecting privacy. Compliance with the law cannot rest only on investigations and penalties. Proactive strategies are equally, and in our view more important in achieving ongoing compliance and respect for the rights of consumers.

Access to quick and effective remedies and the role of the OPC

The CPPA would give the OPC order-making powers and allow the OPC to recommend the imposition of very large penalties on organizations that violate the law, but these provisions are subject to limitations and conditions such that consumers would not have access to quick and effective remedies. To achieve this objective would require important amendments to the Bill.

(i) Limits on violations subject to administrative penalties

The most striking limitation on penalties is found in s. 93(1) of the CPPA, which lists only very few violations as subject to administrative penalties. This list does not include obligations related to the form or validity of consent, nor the numerous exceptions to consent, which are at the core of protecting personal information. It also does not include violations to the principle of accountability, which is supposed to be an important counterbalance to the increased flexibility given to organizations in the processing of data.

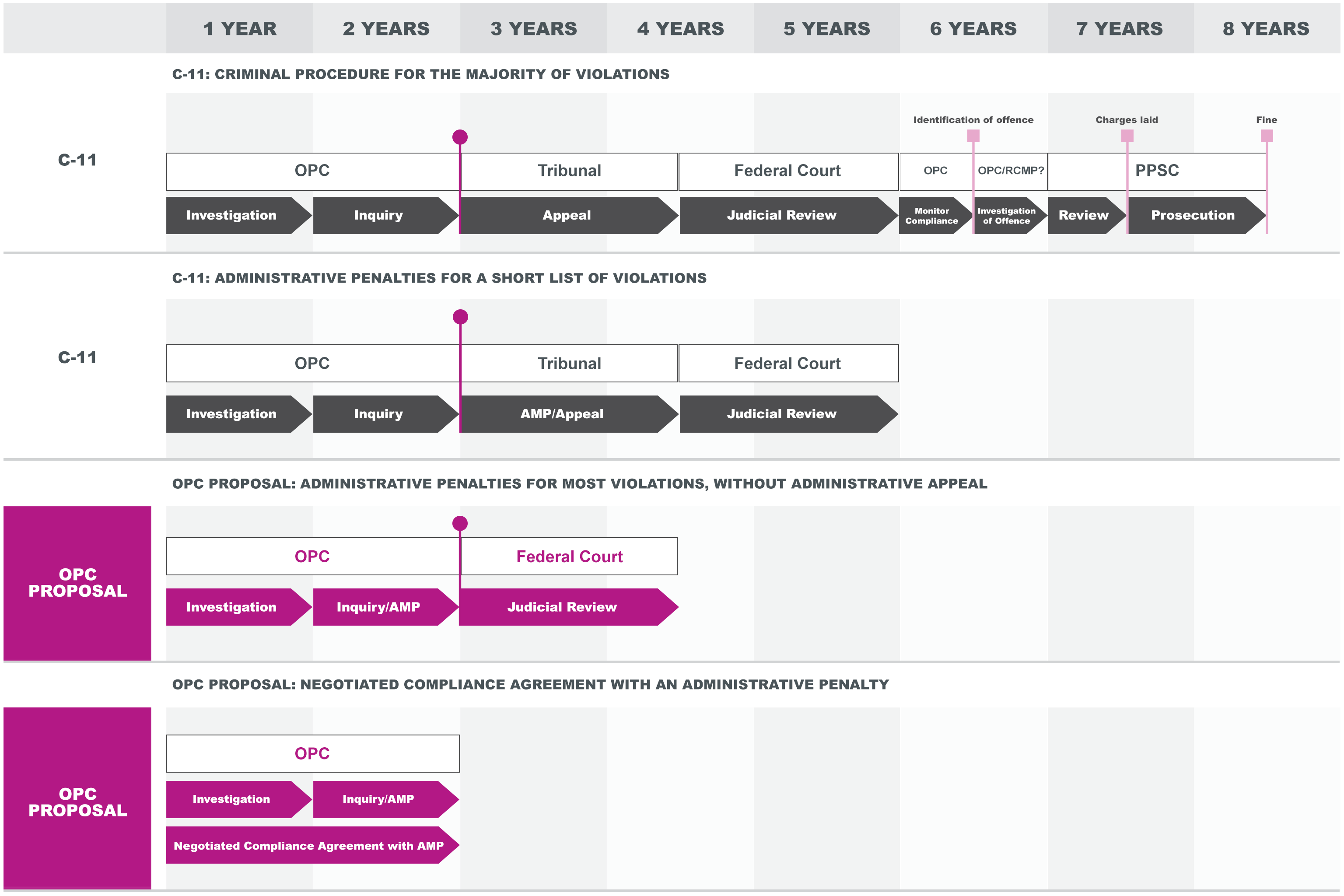

Only criminal penalties would be available for violations of these rights and obligations, following a process that in our view would take seven (7) years on average. This process would include an order made by the OPC and a refusal to comply by the organization. With the amendments we recommend, the process could take fewer than two (2) years. Notably, we recommend that most if not all violations of the CPPA could be subject to administrative penalties, following a notice by the OPC giving the organization a last opportunity to comply with the law. Criminal sanctions would be reserved for the most egregious violations.

(ii) The Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal

Among the checks and balances imposed on the OPC would be the creation of an additional layer of appeal in the form of the Tribunal. According to the government, this would ensure both fairness to organizations and access to quick and effective remedies for consumers.

To reiterate, the OPC welcomes accountability for its actions. We respectfully suggest that the new Tribunal is both unnecessary to achieve greater accountability and fairness (a role already fulfilled by the Federal Court), and counter-productive in achieving quick and effective remedies. We recommend that this new layer not be added to a process that can already be quite long. However, should Parliament decide that the new Tribunal would add value, we recommend that its composition be strengthened and that appeals from its decisions go directly to the Federal Court of Appeal.

While our submissions elaborate on our analysis of this issue, I wish to emphasize a few points here. First, the addition of such an administrative layer between the privacy regulator and the courts does not exist in other jurisdictions. Second, the experience of these jurisdictions, including some Canadian provinces, shows that effective structures can be created within data protection authorities to enhance fairness through the separation of enforcement and adjudicative functions. Third, the OPC is already subject to judicial review, and only once in its almost 40-year history was a decision it had made found not compliant with natural justice.

Fourth and probably most important, the fact that the OPC would not be authorized to impose administrative penalties, and that its orders would be subject to appeal to another administrative structure before reaching the courts, would reduce the incentive organizations have under the model in place in other jurisdictions, to come to a quick agreement with the regulator. In these jurisdictions, where the data protection authority is the final administrative adjudicator and where it can impose financial penalties, organizations have an interest in coming to a negotiated settlement when, during an investigation, it appears likely a violation will be found and a penalty may be imposed. Unfortunately, the creation of the Tribunal would likely incentivize organizations to “play things out” through the judicial process rather than seek a negotiated settlement with the OPC, thus depriving consumers of quick and effective remedies. Sadly, but truly, justice delayed is justice denied.

(iii) Giving the regulator tools to be effective in protecting consumers

Bill C-11 would impose several new responsibilities on the OPC, including the obligation to review codes of practice and certification programs, and advice to individual organizations on their privacy management programs. We welcome the opportunity to work with businesses in these ways in ensuring their activities comply with the law. However, adding new responsibilities to an already overflowing plate means the OPC would not be able to prioritize its activities, based on its expert knowledge of evolving privacy risks, to focus on what is likely most harmful to consumers.

The issue here is not primarily money, although in our view additional resources will be required. The issue is whether the OPC should have the legal discretion to manage its caseload, respond to the requests of organizations and complaints of consumers in the most effective and efficient way possible, and reserve a portion of its time for activities it initiates, based on its assessment of risks for Canadians.

An effective regulator is one that prioritizes its activities based on risk. No regulator has enough resources to handle all the requests it receives from citizens and regulated entities. Yet Bill C-11 adds responsibilities, including the obligation to decide complaints before consumers may file a private right of action, imposes strict time limits to complete our activities, and adds no discretion to manage our caseload. This is not only untenable for us as a bureaucratic organization. It would deprive us of a central tool to ensure we can be effective in protecting Canadians.

We therefore make a number of recommendations under this theme, to ensure we can both be responsive, to the extent our resources allow, to individual requests made by complainants and organizations, and effective as a regulator for all Canadians.

Conclusion

The past few years have opened our eyes to the exciting benefits and worrying risks that new technologies pose to our values and to our rights. The issues we face are complex but the path forward is clear. As a society, we must project our values into the laws that regulate the digital space. Our citizens expect nothing less from their public institutions. It is on this condition that confidence in the digital economy, damaged by numerous scandals, will return.

OPC review of C-11 – context

Prior to presenting our specific comments on the Bill, it will be of value to provide a brief overview of the lens through which we viewed the Bill.

Our overall position on privacy law reform can also be found in the Commissioner’s message from our 2018-19 and 2019-20 annual reports, as well as the Commissioner’s statement before the Quebec National Assembly on Bill 64, An Act to modernize legislative provisions as regards the protection of personal information, and in a September 2020 Hill Times op-ed, titled The value of data, the values of privacy.

Our submission is based in part on our experience as a regulator and our frequent and deep involvement in privacy matters with other data protection authorities in Canada and across the world. Our recommendations are grounded in precedents, best practice, and research, which has been growing rapidly in recent years and thus forms an impressive pool of knowledge from which we can draw. These recommendations are closely aligned with existing legislation, frequently cited in this submission, that domestic and international jurisdictions have adopted. We also refer to work that the OPC has commissioned by leading Canadian researchers such as Ignacio Cofone (on artificial intelligence) and Teresa Scassa (on privacy as a human right and on trans-border data flows).

Finally, the OPC agrees that granting organizations the flexibility to responsibly innovate is essential in a modern, data-driven economy – and that this will require new exceptions to consent. Laws should permit the use of personal information in the public interest, and responsible processing of personal information can serve public goods such as health, economic growth, and better public policies and programs.

Artificial intelligence (AI), for instance, holds immense promise, including helping to address some of today’s most pressing issues. It can detect and analyze patterns in medical images to assist doctors in diagnosing illness, improve energy efficiency by forecasting demand on power grids, deliver highly individualized learning for students, and manage traffic flows across various modes of transport to reduce accidents and save lives. AI also allows organizations to innovate in consumer products as well as in business operations, such as automating quality control and resource management. AI stands to increase efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness – factors that are critical to the economic recovery and long-term prosperity of the country.

However, the benefits of drawing value from data should not come by ignoring privacy or giving it a secondary role as a suggested best practice that can be too easily set aside for other goals. On the contrary, privacy and innovation are not conflicting values and can be achieved at the same time.

This increased flexibility for organizations to innovate should be exercised within a legal framework that entrenches privacy as a human right. At a minimum, the law should provide objective standards, democratically adopted in the public interest, that assure consumers that their participation in the digital world will no longer depend on their “consent” to practices imposed unilaterally by the private sector. Moreover, the granting of greater flexibility in data processing should be accompanied by increased corporate responsibility. It is on these conditions that trust, eroded by frequent violations of the right to privacy, will return.

Our comments, in brief

Navdeep Bains, the Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry at the time the Bill was introduced has stated that there are three pillars to Bill C-11: enhancing consumer control, enabling responsible innovation, and ensuring a strong enforcement and oversight mechanism. Parliament now has a significant job in front of it – including, in our opinion, a need to fully examine whether the Bill appropriately realizes these pillars, and achieves the ultimate end of protecting the privacy of Canadians in the modern, data-centric era.

Despite Bill C-11’s ambitious goals, our view is that in its current state the Bill would represent a step back overall for privacy protection. There are serious problems with this Bill. It seeks to address most of the privacy issues relevant in a modern digital economy, but in ways that are frequently misaligned and less protective than the laws of other jurisdictions. However, with some important amendments, the Bill could become a strong piece of legislation that effectively protects the privacy rights of Canadians, while encouraging responsible economic activity.

This submission thus sets out a series of recommended changes, broken into three themes:

- a better articulation of the weight of privacy rights and commercial interests

- specific rights and obligations

- access to quick and effective remedies and the role of the OPC

Recommended amendments

Theme one: Weighting of privacy rights and commercial interests

Our Office has argued for a modernization of laws that would give organizations greater flexibility to use personal information without consent for responsible innovation and socially beneficial purposes, but within a legal framework that would entrench privacy as a human right and as an essential element for the exercise of other fundamental rights.

Bill C-11 maintains that privacy and commercial interests are competing interests that must be balanced. In fact, the Bill arguably gives more weight to commercial interests than the current law by adding new commercial factors to be considered in the balance, without adding any reference to the lessons of the past twenty years on technology’s disruption of rights.

In our view, it would be normal and fair for commercial activities to be permitted within a rights framework, rather than placing rights and commercial interests on the same footing. Generally, it is possible to concurrently achieve both commercial objectives and privacy protection. This is how we conceive responsible innovation. However, when there is a conflict, we believe rights should prevail.

In this section, we set out a number of potential amendments that would help to achieve a more appropriate weighting of privacy rights and commercial interests.

Human rights framework

In advance of the 2018-19 Annual Report to Parliament, the OPC engaged Dr. Teresa Scassa in an examination of whether and how a human-rights based approach to data protection law could be implemented in Canada.Footnote 2 As described by Dr. Scassa:

A human rights-based approach to privacy is one that places the human rights values that underlie privacy protection at the normative centre of any privacy legislation. Approaching privacy as a human right does not eliminate the need to balance privacy with competing rights and interests (some of which also have constitutional status). Rather, it acknowledges the nature and value of privacy as a human right so as to give privacy its appropriate weight in any balancing exercise.

Dr. Scassa highlights that privacy is clearly recognized as a basic human right in international treaties to which Canada is a signatory including the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (see Article 12) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (see Article 17). Not only has the Federal Court specifically referred to PIPEDA as quasi-constitutionalFootnote 3, the Supreme Court of Canada has also repeatedly recognized the quasi-constitutional nature of privacy rights “because of the fundamental role privacy plays in the preservation of a free and democratic society.”Footnote 4

Beyond this recognition of the status of privacy, approaching privacy through a human rights lens can also allow it to evolve. Initial conceptions of privacy focused on the individual, centering consent as a means of permitting control (at least in theory) over access to and use of personal information.

However, as noted by Dr. Scassa, there is a growing recognition that breaches of individual privacy can produce collective harms. For instance, though mass surveillance impacts individuals, it may cause collective harm through larger-scale behavioural changes or through a widespread lessening of dignity and autonomy. As well, contemporary data analytics can reduce individuals to shared characteristics within groups, potentially leading to both individual and collective harms being experienced when assumptions made about the group’s characteristics are applied to both the group and to those considered part of it. Here, privacy harms are closely tied to the right to equality and to be free from discrimination.

[A further examination of the need for a rights-based framework is available in the aforementioned annual report; we refer you to that document for further discussion.]

A human rights-based framework does not, however, require privacy legislation to come at the cost of innovation. In fact, it should be seen as an opportunity for Canada. In its submission to a review of the Australian Privacy Act, the Office of the Australian Privacy Commissioner writes:

However, balancing privacy rights with economic, security and other important public interest objectives is not a zero-sum game. There are mutual benefits to individuals and regulated entities if the rights and responsibilities in the [Australian] Privacy Act are in the correct proportion. Effective privacy laws support economic growth by building trust and confidence that innovative uses of data are occurring within a framework that promotes accountability and sustainable data handling practices. Increasing individuals’ confidence in the way their personal information is managed will likely lead to greater support for services and initiatives that propose to handle this information. These are essential ingredients to a vibrant digital economy and digital government.

We have made similar arguments, including in our 2018-19 annual report:

The incorporation of a rights-based framework in our privacy laws would help support responsible innovation and foster trust in government, giving individuals the confidence to fully participate in the digital age. We are certain that both private and public sector organizations will be able to continue to innovate and thrive in an environment that both supports and encourages innovation and recognizes and protects the privacy rights of individuals. In fact, a greater focus on privacy rights, responsible practices, and transparency could assist the business community and public sector in ensuring that they remain competitive and relevant on both a domestic and international level given global developments in this regard.

In fact, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella highlighted that trust in personal data use is fundamental to ensuring economic growth, in his comments at the 2020 World Economic Forum:

The one way we can in fact not only have lack of economic growth, we can go backwards, is if you don’t have trust in the very factor of production that’s supposed to fuel the fourth industrial revolution. So, whether it’s cyber, whether it’s privacy…AI ethics or Internet safety, these are all big topics where we will need global norms to ensure that there is trust in technology and we, as the platform creators, will have to do our part in it.Footnote 5

In other words, protecting privacy as a fundamental right is entirely in line with the government’s objective of fostering trust in the digital and information-based economy.

A year prior, in addressing the 41st International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners, Microsoft President, Brad Smith, noted:

Privacy is not just a fundamental human right. It is a foundational right.Footnote 6

Earlier this year, in his remarks at the Computers, Privacy and Data Protection conference, Apple CEO Tim Cook said:

If we accept as normal and unavoidable that everything in our lives can be aggregated and sold, we lose so much more than data …We lose the freedom to be human.Footnote 7

In his testimony given before the House of Commons ETHI Committee Study in May 2018, Jim Balsillie, former co-CEO of Research in Motion and co-founder of the Council of Canadian Innovators stated:

Canadians need to be formally empowered in this new type of economy, because it affects our entire lives … personal information has already been used as a potent tool to manipulate individuals, social relationships, and autonomy. Any data collected can be reprocessed, used, and analyzed in the future, in ways that are unanticipated at the time of collection. This has major implications for our freedom and democracy … It is the role of liberal democratic government to enhance liberty by protecting the private sphere. The private sphere is what makes us free people.

It should also be noted that recognizing privacy as a human right is not incompatible with a principles-based data protection framework and need not result in a law that is overly prescriptive. The prescriptive nature of a law is often related to the level of detail associated with the definition of specific privacy principles. A rights-based framework operates at the same level of generality as a principles-based law. Neither is strictly prescriptive. They are both equally flexible and adaptable to regulate a rapidly changing environment such as the world of technology and the digital economy.

As there is a growing appreciation of privacy as a right that is linked to the exercise of other human rights, a clearer articulation of the meaning, scope and importance of this right is required. Thereby, for example, the challenges of the big data society have made it more urgent to make clear the connections between data protection and the human rights footing on which it rests. The adoption of a rights based framework would maintain flexibility but provide necessary guidance as to the underlying values, principles and objectives that should shape the interpretation and application of the statute, particularly where there may be some ambiguity in those provisions. This approach would offer consumers much better assurance that their rights would be respected by the organizations to which they entrust their personal information.

Having set out our rationale for the inclusion of a human rights-based framework in the CPPA, we make the following recommendations.

Addition of a preamble

Our first recommendation is to once again propose the CPPA include a preamble. We previously proposed a preamble to a revised PIPEDA in our 2018-19 Annual Report and set out proposed wording. Such a preamble would serve to provide guidance as to the values, principles and objectives that should shape the interpretation and application of the CPPA. For instance, the addition of these clauses would make clear to those interpreting s. 12(1) that “appropriate” and therefore permissible purposes under the law are to be assessed with regard to the rights and values mentioned, while recognizing the legitimate interest of organizations to process personal information responsibly.

Some raised objections to this proposal on the basis that it would be inconsistent with the constitutional grounding of the Act in the federal trade and commerce power. However, if the law is in pith and substance about regulating trade and commerce then it can include privacy protections, including privacy as a human right. In fact, a preamble would strengthen the constitutional footing of the legislation by identifying the purpose and background to the legislation.Footnote 8 The absence of a preamble has been noted by the Supreme Court as creating difficulties in carrying out a division of powers analysis.Footnote 9 Given the constitutional doubts that have been raised around PIPEDA, a preamble would provide much needed interpretive guidance to the courts about the law’s objective and constitutional basis.

We therefore propose the following preamble based on the version from our 2018-19 Annual Report with some additions to better capture the constitutional basis of the CPPA in the federal trade and commerce power:

Proposed preamble:

WHEREAS privacy is a basic human right of every individual and a fundamental value reflected in international human rights instruments to which Canada is a signatory;

WHEREAS the right to privacy protects individual autonomy and dignity, and is linked to the protection of reputation and freedom of thought and expression;

WHEREAS privacy is essential to relations of mutual trust and confidence that are fundamental to the Canadian social fabric and economy;

WHEREAS privacy is essential to the preservation of democracy and the full and meaningful enjoyment and exercise of many of the rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms;

WHEREAS the current and evolving economic and technological context facilitates the collection of massive quantities of personal data as well as the use of these data, whether in identifiable, aggregate or anonymized forms, in ways that can adversely impact individuals, groups and communities;

WHEREAS the processing of personal data should be designed to serve humankind and, in particular, must respect the best interests of children;

WHEREAS the digital and information-based economy has the potential to bring economic, social and cultural benefits to the people of Canada;

WHEREAS the objective of this law is to promote and support electronic commerce by ensuring that individuals can engage in the digital and information-based economy with the knowledge that their privacy rights will be respected, thereby ensuring the benefits of this economy can be realized for all;

WHEREAS this law protects the privacy rights of individuals while recognizing the legitimate interest of organizations to collect, use and disclose personal information for purposes that a reasonable person would consider appropriate in the circumstances and in ways that do not represent surveillance;

WHEREAS the right to privacy must be balanced with other fundamental rights such as the right to freedom of expression in circumstances in which the collection, use or disclosure of personal information serves a legitimate public interest;

AND WHEREAS this statute has been recognized by the courts as being quasi-constitutional in nature;

Recommendation 1: That the CPPA be amended to introduce the proposed preamble.

Revised sections 5, 12, and 13

In addition to including a preamble, we believe that amendments to sections 5, 12 and 13 of the CPPA can introduce a more appropriate weighting of privacy rights and commercial interests while strengthening the law’s grounding in Parliament's jurisdiction to legislate in respect of trade and commerce under the Constitution Act, 1867.

The amendments we are proposing build on the existing structure of ss. 3 and 5(3) of PIPEDA, to become ss. 5 and 12 of the CPPA. Within this structure, section 5 of the CPPA already recognizes “the right to privacy of individuals.” We also note that sections 12 and 13 incorporate aspects of necessity and proportionality, concepts derived from human rights law, in order to assess whether an infringement of privacy is reasonable. We are proposing amendments to these provisions to ensure that more appropriate weight is given to the right to privacy, all within a structure previously approved by Parliament and, therefore, likely constitutional.

Section 5

Section 5 – the CPPA’s purpose clause – should be amended to no longer refer to privacy rights in a technical and narrow sense, and instead recognize their true nature as a quasi-constitutional right. It should also provide a more appropriate weighting for privacy rights by adding privacy considerations to balance the new economic factors. Lastly, it should provide a more clear statement of the law’s purpose and constitutional grounding. As with the preamble, these changes will make the law stronger, not weaker, from a constitutional perspective.

Our proposal, which seeks to more clearly state the purpose of the legislation, is set out in the box below.

In the same way that the purpose clause provides new context for the interpretation of business purposes it should provide new context and clarification to the reference to privacy rights.

The reference to fair and lawful we are proposing here mirrors PIPEDA Principle 4, Clause 4.4 (“Information shall be collected by fair and lawful means”), paragraph 7 (Principle 1) of the OECD Guidelines governing the protection of privacy and trans-border flows of personal data (personal data “should be obtained by lawful and fair means and, where appropriate, with the knowledge or consent of the data subject”), as well as Article 5(1)(a) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (“personal data shall be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner”).

Recommendation 2: That section 5 of the CPPA be amended as follow:

In an era in which significant economic activity relies on the analysis, circulation and exchange of personal information and its movement across interprovincial and international borders, the purpose of this Act is to establish rules to govern the protection of personal information to promote confidence and therefore the sustainability of information-based commerce by establishing rules to govern the protection for the lawful, fair, proportional, transparent and accountable collection, use and disclosure of personal information in a manner that recognize

- the fundamental right of privacy of individuals,

with respect to their personal informationthe need of organizations to collect, use or disclose personal information for purposes and in a manner that a reasonable person would consider appropriate in the circumstances, and- where personal information moves outside Canada, that the level of protection guaranteed under Canadian law should not be undermined.

Section 12

Next, we recommend amendments to subsection 12(1).

First, we believe that it would be beneficial to make explicit that an examination of appropriateness requires an assessment of not only the organization’s purposes but also the means by which it seeks to achieve that purpose. This would not be a novel measure, but rather a codification of how the equivalent subsection in PIPEDA (ss. 5(3)) has been interpreted and applied by the Courts and our Office. We have proposed a similar reference in the purpose clause mentioned above.

Recommendation 3: That subsection 12(1) of the CPPA be amended as follows:

An organization may collect, use or disclose personal information only for the purposes and in a manner that a reasonable person would consider appropriate in the circumstances.

Second, subsection 12(2) and the factors it describes should also be amended.

Subsection 12(2) should be amended in two ways. First, a reference should be added to the appropriateness of the manner of collection, use or disclosure, and not only their purposes, to mirror the proposed amendment to subsection 12(1). A proportionality analysis includes an assessment of both purposes and means.

Additionally, the proposed enumeration of factors which must be taken into account in evaluating appropriateness is unduly inflexible and does not reflect the approach of the Federal Court. The Federal Court has held (in Eastmond) that PIPEDA’s s. 5(3) – the precursor to the CPPA’s s. 12 – required an assessment of appropriateness “in a contextual manner looking at the particular circumstances of why, how, when, and where collection takes place … all of which suggests flexibility and variability in accordance with the circumstances.” The Federal Court of Appeal has also recognized that the test of what a reasonable person would consider appropriate must be assessed against the particular circumstances that exist at a given time.Footnote 10

So, whereas Federal Court jurisprudence requires a contextual assessment of appropriateness, s. 12(2) of the CPPA would dictate a consideration of specific factors, some of which may be irrelevant in some circumstances, to the exclusion of others that may well be relevant.

As such, we propose new text for subsection 12(2) which clarifies that the factors to be considered in an assessment of appropriateness will vary by context, and that the enumerated factors are non-exhaustive.

Recommendation 4: That subsection 12(2) of the CPPA be amended as follows:

The following factors must to be taken into account in determining whether the purposes and manner referred to in subsection (1) are appropriate include:

…

(g) any other relevant factors in the circumstances

Lastly, in this section, we also recommend amendments to the factors set out in paragraphs 12(2)(a) to (e). In particular:

First, if subsection 12(2) is not amended to clarify that the application of the factors will vary based on the circumstances of the collection, use or disclosure, we recommend the deletion of the first factor (sensitivity of the information). Without this amendment, there is an implication that the appropriateness of the collection, use or disclosure of information deemed ‘not sensitive’ need not be as closely examined as that of more sensitive information. However, our preference would be to retain this criteria as part of a contextual, non-exhaustive list of factors.

Paragraphs (d) and (e) should also be amended to strike a more appropriate balance between the right to privacy and commercial interests. In the case of paragraph (d) – which speaks to the existence of less intrusive means of achieving a purpose at a “comparable cost and with comparable benefits,” while costs and benefits to the organization are relevant factors to what is, essentially, a proportionality analysis, the notion that slightly higher costs might justify more privacy intrusive measures is plainly inappropriate. Similarly, paragraph (e) – which speaks to whether benefits are proportionate to the individual’s loss of privacy – ends with the consideration of mitigations implemented by the organization, without equally considering aggravating factors with respect to the magnitude of the loss of rights. For both s. 12(d) and (e), we recommend the deletion of the qualifier at the end of the paragraph not due to irrelevance, but to address a lack of balance.

Paragraph (e) is also too narrow in its reference to privacy, in that it does not characterize privacy as a fundamental or quasi-constitutional right. The benefits obtained by an organization should not be weighed solely against a loss of privacy in a narrow and technical sense, but against all fundamental rights and interests such as an individual’s autonomy, dignity or equality rights, that are impacted by a collection, use or disclosure. We have proposed two options for revised language.

First, and our preference, is to weigh broadly the individual’s loss of privacy or other fundamental rights and interests as the counterbalance to any benefits obtained. In the alternative, we would propose language as suggested by the Government of Canada in the Department of Justice paper “Respect, Accountability, Adaptability: A public consultation about modernization of the Privacy Act”, which recognizes the association of privacy with “dignity, autonomy, and self-determination.” While we believe there is significant benefit to the breadth of our first formulation, which recognizes the relationship between privacy and the exercise of other fundamental rights, inclusion of the language found in the Privacy Act discussion paper would nonetheless be a meaningful improvement.

Lastly, we have proposed two additional factors. First, we recommend that if our proposal to refer to the “manner” of the collection, use or disclosure in s. 12(1) and the opening words of s. 12(2) is accepted, then the list of factors in s. 12(2) should include one relevant to means. We suggest that this factor require consideration of whether information was collected, used or disclosed in a fair, lawful and transparent means.

Second, as noted above, a new final factor under (g) – ‘any other relevant factors(s) in the circumstances’ – is being proposed to emphasize that the list of factors is not exhaustive.

Recommendation 5: That the factors set out in subsection 12(2) of the CPPA be amended as follows:

- the sensitivity of the information; [delete if the proposed amendment make to subsection 12(2) non-exhaustive is not adopted]

- whether the purposes represent legitimate business needs of the organization;

- the effectiveness of the collection, use or disclosure in meeting the organization’s legitimate business needs;

- whether there are less intrusive means of achieving those purposes

at a comparable cost and with comparable benefits;and - whether the individual’s loss of privacy or other fundamental rights and interests is proportionate to the benefits

in light of any measures, technical or otherwise, implemented by the organization to mitigate the impacts of the loss of privacy on the individual;[Alternatively, the clause could be amended as: “whether the individual’s loss of privacy, dignity, autonomy and self-determination is proportionate to the benefits.”]

- [if subsections 12(1) and 12(2) are amended as proposed to refer to means] whether the personal information is collected, used or disclosed in a fair, lawful and transparent manner; and

- any other relevant factor(s) in the circumstances.

Section 13

Section 13 incorporates in the CPPA the data minimization principle, an adaptation into privacy law of the necessity analysis under human rights law. In fact, s. 13 uses the word “necessary” in relation to the collection of personal information.

In the laws of other jurisdictions, data minimization requires that only personal information necessary for “specified, explicit and legitimate purposes” may be collected: see for instance article 5(1)(b) of the GDPR. Article 15 of Japan’s Protection of Personal Information Act requires that purposes must be defined “as explicitly as possible.” The current federal law in Canada, in Principle 4.3.3 of PIPEDA, also makes reference to “explicitly specified, and legitimate purposes.”

This requirement that purposes be specific or explicitly specified has been removed in Bill C-11, giving organizations much more discretion in defining the purposes for which they will collect information. With the result that, conceivably, organizations could seek consent for vague and mysterious purposes, such as “improving your consumer experience.”

As such, amending section 13 to require that purposes be specific, explicit and legitimate would both strengthen the necessity analysis and make consent more meaningful by ensuring that the purposes at the centre of consent are understandable.

Recommendation 6: That subsection 13 of the CPPA be amended as follows:

The organization may collect only the personal information that is necessary for the specific, explicit, and legitimate purposes determined and recorded under subsection 12(3).

Finally, with respect to the human rights framework, we will address the issue of key definitions within the CPPA.

Other considerations

Definition of personal information

As discussed in the OPC’s recent publication, A Regulatory Framework for AI: Recommendations for PIPEDA Reform (AI paper) and elaborated in the accompanying paper from Professor Ignacio Cofone, an important measure related to the human-rights approach would be to amend the definition of personal information so that it explicitly includes inferences drawn about individuals.

Inferences refer to a conclusion that is formed about an individual based on evidence and reasoning. In the age of AI and big data, inferences can lead to a depth of revelations, such as those relating to political affinity, interests, financial class, race, etc. This is important because the misuse of such information can lead to harms to individuals and groups in the same way as collected information – a position confirmed by the Supreme Court in Ewert v. Canada. In fact, as noted by the former European Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, “[m]ore often than not, it is not the information collected in itself that is sensitive, but rather the inferences that are drawn from it and the way in which those inferences are drawn, that could give cause for concern.”

General support for the idea that inferences constitute personal information can be found in past OPC decisions and Canadian jurisprudence. For instance, the OPC has found that credit scores amount to personal information (PIPEDA Report of Findings #2013-008, among others), and that inferences amount to personal information under the Privacy Act (Accidental disclosure by Health Canada, paragraph 46). This is also consistent with the Supreme Court’s understanding of informational privacy, which includes inferences and assumptions drawn from information.Footnote 11

However, despite this, there remains some debate as to how inferences are regarded. Some view them as an output derived from personal information, like a decision or an opinion might be, and argue these are outside the purview of privacy legislation. Given that inferences are typically drawn using an analytical process, such as through algorithms, others claim that these are products created by organizations using their own estimations, and that they do not belong to individuals.

In light of these conflicting viewpoints, we believe the law should be clarified to include explicit reference to inferences under the definition of personal information. This would be in accordance with modern privacy legislation such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which explicitly includes inferences in its definition of personal information. The OAIC’s proposed amendments to the Australian Privacy Act also support this approach.

Importantly, even where there is agreement that inferences are personal information, the fact that they could reveal commercial trade secrets is used by some as a basis to deny individuals certain privacy rights, such as to access or correction. Our recommendations for automated decision-making propose a fair way to resolve this contention.

Recommendation 7: That the definition of personal information be amended to expressly include inferred information.

Definition of sensitive information

Under subsection 12(2)(a), one of the factors to consider when determining whether a reasonable person would consider an organization’s purposes appropriate under the circumstances is “the sensitivity of the information.” This is also a consideration that organizations must take into account with respect to the form of consent (s. 15(4)), the development of an organization’s privacy management program (s. 9(2)), the level of protection provided by security safeguards (s. 57(1)), the evaluation of whether a breach creates a real risk of significant harm (s. 58(8)), and other requirements within the CPPA.

While the OPC and the courts have provided some interpretations of sensitive information, it would be preferable to have a legislative definition that sets out a general principle and is context-specific, followed by an explicitly non-exhaustive list of examples (such as those included in article 9 of the GDPR). This would provide greater certainty for organizations and consumers as to the interpretation of the term. For instance, such a definition might read:

Sensitive information means personal information for which an individual has a heightened expectation of privacy, or for which collection, use or disclosure creates a heightened risk of harm to the individual. This may include, but is not limited to, information revealing racial or ethnic origin, gender identity, sexual orientation, political opinions, or religious or philosophical beliefs; genetic information; biometric information for the purpose of uniquely identifying an individual; financial information; information concerning health; or information revealing an individual’s geolocation.

Further, we note that the French version of PIPEDA currently refers to “renseignements … sensibles” contrary to the CPPA which proposes to rely on the term “de nature délicate”. Quebec’s Bill 64 also refers to “renseignement personnel sensible”, while the GDPR uses the term “données sensibles”. To ensure consistency with the current statute and to promote alignment with the laws of Quebec and the EU, we suggest that the French version of the CPPA revert to the term “sensible” as opposed to “de nature delicate”.

Recommendation 8: That a definition of sensitive information be included in the CPPA, that would establish a general principle for sensitivity followed by an open-ended list of examples.

Definition of commercial activity

For what we understand are reasons of clarity, rather than a desire to change the scope of the activities governed by federal private-sector privacy law, the CPPA would add a contextually-dependent approach (adding the words “taking into account an organization’s objectives…”) to characterizing commercial activity. We find this very interesting, but are concerned that this change in structure from the PIPEDA definition may exclude certain activities that are commercial in nature but carried out by organizations that overall do not have commercial objectives. These activities, undertaken by charities, professional associations or non-profit organizations, are currently governed, properly in our view, by PIPEDA.

To ensure commercial activities carried out by non-commercial entities continue to be governed by privacy law, we recommend that the definition be divided in two paragraphs, one referring to commercial activities carried out by any entity, whether commercial or not, and the other referring to any activity, commercial or not, carried out by a commercial organization. This would maximize, within a reasonable understanding of what is “commercial”, privacy protection for all activities related to personal data.

Recommendation 9: That the definition of commercial activity be clarified as follows:

Commercial activity means:

- any particular transaction, act or conduct

or any regular course of conductthat is of a commercial character, whether or not it is committed by an organization whose general objectives are of a commercial character; or - any regular course of conduct that is of a commercial character, including any activity that is part of a regular course of conduct that is of a commercial character taking into account an organization’s objectives

for carrying out the transaction, act or conductand the context in which it takes place, the persons involved and its outcome.

Political Parties

Related to the scope of activities governed by the CPPA, we affirm our position that political parties should be subject to privacy obligations, and that it would be reasonable for federal political parties to be regulated under the CPPA.

The question of whether federal political parties should be subject to privacy regulation – one of the matters discussed in ETHI’s 2018 report, Democracy Under Threat – is, at this point, largely no longer a contentious one. Political parties collect significant amounts of information about voters (as well as volunteers, employees, and candidates) and use this data for micro-targeted political campaigning, among other things. These practices have the potential to have significant privacy impacts and, done improperly, threaten trust in the democratic system. Jurisdictions around the world – including the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), New Zealand, Argentina and Hong Kong, not to mention British Columbia and, if Bill 64 is adopted, Quebec – have privacy laws that govern political parties, and even a decade ago (long before the Cambridge Analytica scandal) an OPC survey found that 92% of Canadians supported the notion that political parties should be subject to some form of privacy regulation.

The question then becomes not whether but how to regulate federal political parties’ collection and use of personal information.

Broadly, there are four options available: inclusion of federal political parties under the CPPA, inclusion under the Privacy Act, amendment of the Canada Elections Act, or introduction of new, standalone legislation. While there are merits to each approach, the timeliness of the first makes it worthy of significant consideration.

While federal political parties do not explicitly fall under the ambit of the CPPA as currently drafted, subsection 6(3) and paragraph 119(2)(c) provide a mechanism by which the Governor-in-Council can list an organization as being subject to the Act. Currently, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has been made subject to the Act in this manner.

That federal political parties are different in nature from commercial organizations must be recognized, but British Columbia and Quebec provide two potential models for accommodating this within a private sector-focused legislation. British Columbia’s Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) does not include any special considerations for political parties, but instead provides an exception to consent for collection of personal information when authorized by law. This, in combination with the BC Election Act, permit (and restrict) the use of voter list information for (and to) the “electoral purposes” for which it was collected. Quebec’s Bill 64, on the other hand, specifically exempts political parties from the application of certain sections of the proposed Act (exemptions which, it should be noted, are not supported by the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec).

We would support a slight variation on the British Columbian approach to regulation. Acknowledging the importance of permitting democratic outreach, an exception to consent could be introduced which narrowly applies to such activities.

Recommendation 10: Subject federal political parties to the CPPA, for example by registering them in the schedule pursuant to subsection 6(3) and paragraph 119(2)(c).

Theme two: Specific rights and obligations

Having considered the overall underpinnings of the legislation, we turn our attention to operational considerations – specifically how this framework will apply in practice. We focus on three particular areas: consent and the exceptions thereto; organizational obligations, and individual data rights.

Valid vs. meaningful consent

One of the proposed pillars of Bill C-11 is to enhance consumers’ control over their personal information. To achieve this, rules governing consent must ensure it is informed and meaningful.

In 2015, section 6.1 was added to PIPEDA to specify that consent would only be considered valid if “it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization’s activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose, and consequence of [the activity to which they are consenting].”

The “understanding” requirement, which is key to the validity of consent, is unfortunately absent from the CPPA. Instead, the Bill seeks to give consumers more control by prescribing elements that must appear in a privacy notice, in plain language. While this seems similar to the approach taken in our 2018 Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent, it is not the case because again, the requirement of “understanding” is missing. Compare our guidelines, which require that purposes for which information is collected must be explained “in sufficient detail for individuals to meaningfully understand what they are consenting to,” with s. 15(3) of the CPPA, which simply requires that consumers be informed of “the purposes for the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information determined by the organization…”

As noted earlier in theme one, under the Bill the purposes “determined by the organization” do not have to be “specific, explicit and legitimate.”

By prescribing elements of information to appear in privacy notices without maintaining the requirement that consumers must be likely to understand what they are asked to consent to, the CPPA does not achieve its goal of giving individuals more control over their personal information; it provides less. This is exacerbated by the open-ended nature of the purposes for which organizations may seek consent.

In our view, this is because the Bill is incorrectly calibrated. We agree that organizations should be able to innovate, to have flexibility in the processing of personal data and to define the purposes for which they wish to collect, use and disclose personal information, but this flexibility should be exercised within a legal framework that provides objective standards, enforced by an independent regulator in the public interest.

As drafted, the Bill places too much emphasis on providing organizations flexibility in defining the purposes for which personal information may be used and in obtaining consumer consent. Legislators should enact objective standards such as the one in section 6.1 of the current Act (the “understanding” factor) and the requirement that purposes be defined in a specific, explicit and legitimate manner, as set out in Principle 4.3.3 of PIPEDA and in the laws of other jurisdictions.

Also relevant to understanding is how information is presented. The CPPA does not speak to format, content structure, or accessibility. Each of these is a factor that contributes to an individual’s understanding of how their personal information is being used. Plain language information that is difficult to find, or presented in a format that makes comprehension difficult, does not lead to understanding (or meaningful consent). Poorly designed or formatted information may ultimately be as inaccessible as poorly drafted language – particularly for individuals who rely on accessibility tools, such as screen readers, or in certain circumstances, minors. As such, we recommend that s. 15(3) speak to the format of information being provided to individuals, in addition to the plain language requirement.

Recommendation 11: That subsection 15(3) of the CPPA be amended as follows:

The individual’s consent is valid only if, at or before the time that the organization seeks the individual’s consent, it provides the individual with the following information, in a manner such that it is reasonable to expect that the individual would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the intended collection, use or disclosure. This information must be presented in an intelligible and easily accessible format, using clear and in plain language.

Next, while the OPC is supportive of subsection 15(4)’s recognition of express consent as the default form of consent, as drafted this provision would allow an organization to rely on implied consent where it “establishes” (in French, “conclure”) that this would be appropriate, in light of listed factors. Bill C-11 therefore seems to give deference to an organization’s conclusion that implied consent is appropriate, as opposed to prescribing an objective assessment of the relevant factors. We recommend that the phrase “the organization establishes that” be removed. As a result, organizations would, of course, continue to determine in the first instance if the objective conditions for implied consent are met, but this assessment would be reviewable independently by the regulator and ultimately the courts, as a matter of law and without improper deference to the organization’s opinion of the law.

Recommendation 12: That subsection 15(4) of the CPPA be amended as follows:

Consent must be expressly obtained unless the organization establishes that it is appropriate to rely on an individual’s implied consent, taking into account the reasonable expectations of the individual and the sensitivity of the personal information that is to be collected, used or disclosed.

Exceptions to consent

Consent, which forms the basis of many data protection laws across the globe, including PIPEDA and the CPPA, is not without its challenges. As outlined in our AI paper, for individuals, long, legalistic and often incomprehensible policies and terms of use agreements make it nearly impossible to exert any real control over personal information or to make meaningful decisions about consent. For organizations, consent does not always work in the increasingly complex digital environment, such as where consumers do not have a relationship with the organization using their data, and where uses of personal information are not known at the time of collection, or are too complex to explain. These shortcomings are more pronounced in certain contexts, such as with AI.

While the CPPA seeks to enhance consent in some respects, it adds important new exceptions to the consent principle. We believe that such an approach is appropriate within the framework of a modern privacy law. Among the lessons of the past twenty years, since PIPEDA was adopted, is that privacy protection cannot hinge on consent alone. In fact, consent can be used to legitimize uses that, objectively, are completely unreasonable and contrary to our rights and values. Additionally, refusal to provide consent can sometimes be a disservice to the public interest when there are potential societal benefits to be gained from use of data.

Several of the new exceptions to consent brought by Bill C-11 are reasonable. We have two main concerns: some exceptions are unreasonably broad; and the Bill fails to associate greater authority to use personal information with greater accountability by organizations for how they will use these permissions.

Business activities (s. 18)

Section 18 permits the collection and use of personal information without the knowledge or consent of individuals for defined business activities, where a reasonable person would expect the collection or use for the activity, so long as it is not for the purpose of influencing an individual’s behaviour or decisions.

For an individual to understand what specific activities may be carried out under paragraphs 18(2)(a) to (f), it is critical that these be defined clearly and be within the expectations of an individual. We do not find that this is the case with respect to 18(2)(b) and 18(2)(e).

Paragraph 18(2)(b) introduces an exception to consent for activities “carried out in the exercise of due diligence to prevent or reduce the organization’s commercial risk.” Without a definition of “commercial risk,” we would note that a plain language interpretation of this term may include any risk to commercial enterprise, such as loss of revenue. This would clearly be unacceptably broad.

If a narrower meaning is intended, such as the possibility of non-payment due to problems such as bankruptcy or insolvency, the language of s. 18(2)(b) should be clarified accordingly.

Recommendation 13: That the scope of the “commercial risk” exception be limited.

More concerning to us, however, is the potential scope of the exception under paragraph 18(2)(e), which relates to activities for which obtaining consent would be impracticable because the organization does not have a direct relationship with the individual.

On one hand, it appears the intent of this provision may be in part to allow for activities such as search engines, but we do not think it achieves this goal. In our opinion, paragraph 18(2)(e) would cover search engines crawling and indexing of the web without consent. However, as this exception relates only to “collection and use,” and not disclosure, it does not appear to permit all aspects of a search engine’s operations such as the display of search results.

The wording of paragraph 18(2)(e) also raises more fundamental concerns. First, we note that the potential scope of activities which could fall under this exception is extremely broad. It is difficult to conceive if there are any real limitations on the kinds of activities which could be pursued by an organization pursuant to this provision. The limit prescribed by s. 18(1)(a), that “a reasonable person would expect such a collection or use for that activity,” utterly fails to provide consumers with any certainty as to how their personal information will be used, moreover, by an organization they likely do not know. This is far removed from giving consumers more control over their personal information.

Among organizations that would appear to benefit from s. 18(2)(e) are data brokers, who could thus have much greater freedom to operate than the organizations with which individuals regularly and directly interact. The business model of data brokers is opaque and creates risks for privacy. They should be more regulated, not granted greater freedom in the use of data without consent.

Lastly, the basis for the exception in paragraph 18(2)(e) simply does not withstand rigorous scrutiny. In general, we note that it would be obvious why the various provisions of s. 18(2) could permit activity without consent. For instance, paragraphs 18(2)(c) and (d) appear intended to enable (in short) network security, and product safety, respectively. Other exceptions to consent in PIPEDA and in the Bill point to specific purposes and activities such as preventing or investigating financial abuse or fraud.

This is not the case with respect to paragraph 18(2)(e). As it is written now, paragraph 18(2)(e) removes the consent requirement from certain activities simply because obtaining consent is impracticable, not because there is an offsetting benefit to justify such an action. In other words, the fundamental principle of consent is put aside for the simple reason that it is impractical to obtain it.