Appendix 3: Cross-border Data Flows and Transfers for Processing - Jurisdictional Analysis

September 28, 2020

1. Cross-border Data Flows

The questions that must be addressed with cross-border data flows are multiple. They include:

- What is the nature and extent of the obligations and legal responsibility of organizations when they transfer data across borders?

- In what circumstances and to what extent should the following factors impact the responsibility of Canadian organizations when data flows across borders?

- The commercial relationship with the organization in the other country

- The measures taken by the Canadian organization to protect the information in the hands of the offshore entity

- The nature of the legal regime in place in the offshore organization’s country

- Where an assessment of another country’s legal system is required, who should carry this out?

- What criteria should guide assessments and what standards should be applied?

- What role does law enforcement/national security access to personal data in the offshore country play in assessing the legitimacy of a transfer?

- What special oversight/enforcement mechanisms might be required?

This section considers how these issues are dealt with under the GDPR, the laws of Australia and New Zealand, Quebec’s Bill 64, and Convention 108+.

i. GDPR

The GDPR’s rules on cross-border data flows are found in Articles 44 to 50. In particular, Article 44 provides that personal data “which are undergoing processing or are intended for processing after transfer to a third country” can only flow across borders if conditions in the GDPR are met by both controller and processor. This also applies to any onward transfer of personal data from the country of processing. Under the GDPR, controllers are responsible for putting in place “appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure and to be able to demonstrate that processing is performed in accordance with this Regulation.”Footnote 1 Any relationship with a processor must be governed by contractual terms that are enforceable by the controller.Footnote 2 Processing is defined broadly to mean:

[…] any operation or set of operations which is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.Footnote 3

Cross border transfers of data for processing are permitted if the European Commission has decided that the country (or a territory or sector within that country) “ensures an adequate level of protection.”Footnote 4 The adequacy of the legal regime in the country of transfer is addressed in Article 45. Where adequacy is found, the transfer does not require any specific authorization.

Article 45 also sets out the factors to take into account in assessing adequacy. These are:

the rule of law, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, relevant legislation, both general and sectoral, including concerning public security, defence, national security and criminal law and the access of public authorities to personal data, as well as the implementation of such legislation, data protection rules, professional rules and security measures, including rules for the onward transfer of personal data to another third country or international organisation which are complied with in that country or international organisation, case-law, as well as effective and enforceable data subject rights and effective administrative and judicial redress for the data subjects whose personal data are being transferredFootnote 5

Also relevant to adequacy are issues of effective supervisory, oversight, and enforcement bodies and their accessibility to data subjects, as well as their degree of co-operation with the supervisory body in the transferor’s country.Footnote 6 The Commission may also take into account the destination country’s international commitments “in particular in relation to the protection of personal data.”Footnote 7

Once the Commission determines that a jurisdiction meets the adequacy assessment, the assessment is subject to periodic review “at least every four years.”Footnote 8 This review takes into account any relevant changes in the jurisdiction’s laws. Because an adequacy finding can be for a country or a particular region or sector within that country, the assessment must specify to what it relates. The Commission has an ongoing monitoring role with respect to developments in other countries.Footnote 9 An adequacy assessment can be revoked or amended if the Commission is of the view that the country/region/sector at issue “no longer ensures an adequate level of protection”Footnote 10 While the adequacy regime can greatly facilitate cross-border data flows under the GDPR, it imposes an ongoing regulatory burden.

An adequacy decision is not the only means by which data may flow from the EU to another country/region/sector. Where there is no adequacy assessment, Articles 46 to 49 of the GDPR provide for alternatives.Footnote 11 One of these is where the entity to which data are transferred in the destination country “has provided appropriate safeguards”.Footnote 12

Article 46(2) sets out a list of appropriate safeguards. Where these safeguards are in place, then data may be transferred without having to seek authorization from a supervisory authority within the EU. The possible safeguards include binding corporate rules,Footnote 13 standard data protection clauses adopted by the Commission,Footnote 14 standard data protection clauses adopted by the national regulator and approved by the Commission,Footnote 15 an approved sectoral code of conduct combined with binding and enforceable commitments of the recipient to apply the appropriate safeguards,Footnote 16 or an approved certification mechanism combined with binding and enforceable commitments of the recipient to put in place appropriate safeguards.Footnote 17 All of these measures require prior Commission or supervisory authority approval. In all cases the availability of enforceable data subject rights is important. Another alternative in art. 46(3), but one which is subject to authorization from the relevant supervisory authority, is the adoption of contractual clauses between the transferor and the recipient.Footnote 18

Where there is no adequacy decision and no appropriate safeguards as per article 46, there is a final set of options provided in article 49 of the GDPR for cross-border data flows. The first of these is based upon the consent of the data subject to the transfer. Where consent is relied upon, it must be explicit, informed, and specific to the particular transfer. It must address the risks associated with the transfer, including that the transfer is being made to a country that “does not provide adequate protection and that no adequate safeguards aimed at providing protection for the data are being implemented.”Footnote 19 Other exceptions require a demonstration of the necessity of the transfer for certain objectives, or the underlying public interest.Footnote 20

The Schrems IIFootnote 21 decision sheds light on how these requirements receive practical application. In Schrems II, the European Court of Justice rejected the adequacy of the EU-US Privacy Shield as a basis for cross-border data transfers. This agreement replaced the EU-US Safe Harbour Agreement which had been invalidated by the Schrems I decision.Footnote 22 The EU-US Privacy Shield was a mechanism whereby companies could self-certify and publicly commit to comply with the privacy framework put in place to ensure an adequate level of protection for personal data (as defined by the GDPR). In invalidating the Privacy Shield, the Court of Justice of the European Union found that “certain programmes enabling access by US public authorities to personal data transferred from the EU to the US for national security purposes, result in limitations on the protection of personal data which are not circumscribed in a way that satisfies requirements”Footnote 23 equivalent to those available under EU law.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly from a Canadian perspective, the Court made two broad findings with respect to the use of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), another GDPR alternative to an adequacy assessment. The European Court of Justice found that such clauses were valid even if they do not bind the authorities of the country to which data is transferred. However, the Court ruled that transfers of data based on SCCs must be suspended or prohibited if SCCs are breached or if it is not possible to honour them. In the case of the US, the Court found that the same requirements of US national security law that doomed the EU-US Privacy Shield were also a barrier to honouring commitments under SCCs. Reliance upon SCCs might be possible, on a case-by-case basis, provided that “US law does not impinge on the adequate level of protection they guarantee.”Footnote 24 Some EU data protection authorities have issued preliminary opinions that the Court’s ruling means that data transfers to the US are no longer possible.Footnote 25 Others have indicated that transfers based on SCCs may still be possible depending upon the parties and the provisions.Footnote 26 Some have indicated that transfers under SCCs are at this point questionable.Footnote 27

A third point is that the Court also found problematic the inability of EU residents to obtain appropriate recourse under US law where data was accessed under national security legislation.Footnote 28 For example, in Schrems II the Court noted that data subjects did not have “actionable rights before the courts against the US authorities.”Footnote 29 This meant that there was a failure to meet the requirement that where data is transferred outside the EU for processing, data subjects have “effective and enforceable rights”.Footnote 30 Under art. 45 of the GDPR, “effective and enforceable data subject rights and effective administrative and judicial redress for the data subjects whose personal data are being transferred” are an essential element of an adequacy finding.

The European Data Protection Board has indicated that although the Schrems II decision does not address other means of facilitating cross-border data transfers, measures such as binding corporate rules are likely also to be affected, “since US law will also have primacy over this tool.”Footnote 31 The impact on other tools remains to be assessed, although the Board indicates that the standard will be one of “essential equivalence”.Footnote 32

Although Schrems II deals with a data transfer to the US, the standards it sets are applicable to data transfers to all countries outside of the EU.Footnote 33 The Court of Justice emphasized that in the absence of an adequacy decision, it was the responsibility of the parties to the data transfer to assess whether the guarantees set out in SCCs or binding corporate rules are capable of being complied with, whether supplementary measures are necessary, and whether, even with supplementary measures, personal information can appropriately be protected.Footnote 34 If it cannot, the transfer cannot take place.

The Schrems II decision makes clear the importance of an adequacy assessment when it comes to dealings with the EU. Such an assessment greatly facilitates cross-border data flows. In the absence of an adequacy assessment, there are other options available to parties. However, they may not be able to overcome the identified deficiencies in the national system of the third country. Even if they are, this may involve considerable effort and expense on the part of the contracting parties.

Using its considerable collective economic clout, the EU has designed a system which relies heavily upon restricting data flows to organizations in jurisdictions where a comparable level of data protection is not available. This comparable level of protection may be achieved by different means. The simplest for organizations is a finding of adequacy. Where there is no adequacy, other options are available, requiring different levels of effort, and considerable involvement of the Commission or national supervisory authorities. As Schrems II makes clear, however, even these measures may be derailed if national security or law enforcement powers in the destination country allow for excessive access to personal data with inadequate recourse for EU data subjects. While such a regime may offer a high level of protection for the personal data of EU residents, it relies upon a level of economic clout that Canada does not have. Further, it is a complex regime that requires substantial government and regulatory resources.

ii. Australia

One of the express goals of Australia’s Privacy Act 1988 (APA)Footnote 35 is to “facilitate the free flow of information across national borders while ensuring that the privacy of individuals is respected.”Footnote 36 The APA addresses cross-border data flows in s. 16C as well as under Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 8 of its Information Privacy Principles.Footnote 37 Like PIPEDA, the APA is framed around the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data. Cross-border transfers are considered to be ‘disclosures’ of personal information.

‘Disclose’ is not a defined term in the APA. However, it has been interpreted by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) to include any act that makes personal information “accessible to others outside the entity and releases the subsequent handling of the information from its effective control.”Footnote 38 The OAIC focuses on the act of disclosure and not the state of mind of the party disclosing. This means that even accidental or unauthorized releases are disclosures.Footnote 39 The OAIC provides examples of disclosures of personal information to overseas recipients. These include where the recipient:

- shares the personal information with an overseas recipient

- reveals the personal information at an international conference or meeting overseas

- sends a hard copy document or email containing an individual’s personal information to an overseas client

- publishes the personal information on the internet, whether intentionally or not, and it is accessible to an overseas recipient.Footnote 40

The OAIC specifies that a disclosure does not take place “until the personal information reaches the overseas recipient.”Footnote 41 In other words, the routing of personal information through offshore servers is a use, not a disclosure.Footnote 42 Further, OAIC guidance provides that offshore cloud storage of personal information is not a disclosure as long as there are binding contracts that limit the cloud services provider and any subcontractors to handling the personal information only for storage purposes, and the Australian entity retains “effective control” over how the information is handled. Such effective control includes “the right or power to access, change or retrieve the personal information”, and to control who can access it and for what purposes.Footnote 43

APP 6 applies to uses and disclosures of personal information. Since a cross border transfer is treated as a disclosure, such transfers must also be compliant with APP 6. In particular, Clause 6.1 provides that “If an APP entity holds personal information about an individual that was collected for a particular purpose [… ], the entity must not use or disclose the information for another purpose.” Thus, a transfer for processing must be for a purpose for which the information was originally collected, unless one of the statutory exceptions to this rule applies.Footnote 44

According to clause 8.1, an “overseas recipient” has to be outside Australia or an external Territory. It explicitly excludes the entity that is disclosing the personal data. This means that transfers from an Australian entity to one of its offices overseas are not subject to the rules for cross border data transfers.Footnote 45 On the other hand, a transfer from an Australian entity to a “related body corporate” will be treated as a transfer to an overseas recipient.Footnote 46

Clause 8.1 of APP 8 provides that in order for a data transfer to take place, an Australian transferor must “take such steps as are reasonable in the circumstances” to ensure that the overseas recipient does not act in a way that leads to a breach. The ‘reasonable steps’ required by Clause 8.1 typically involve enforceable contractual arrangements.Footnote 47 The OAIC does not provide Standard Contractual Clauses for inclusion in any transfer agreement. However, it provides guidance in the form of a list of considerations for contractual arrangements.Footnote 48 In addition, the OAIC has published a list of factors that it will take into account in assessing whether reasonable steps have been taken in any compliance monitoring process such as an audit.Footnote 49 These factors include the sensitivity of the personal information, the risk of harm to individuals, and technical safeguards put in place by the overseas recipient.Footnote 50 While an entity can take into account the burden, time and cost of providing adequate protection, the OAIC cautions that “an entity is not excused from ensuring that an overseas recipient does not breach the APPs by reason only that it would be inconvenient, time-consuming or impose some cost to do so.”Footnote 51

Clause 8.2 provides that clause 8.1 does not apply to cross-border data transfers where the Australian entity “reasonably believes” that certain circumstances exist.Footnote 52 The first of these circumstances is where the recipient is subject to a law or “binding scheme” in their own country that offers at least a “substantially similar” protection to what is available under the APPs and there are mechanisms that data subjects can access to enforce the law or binding scheme. Having a “reasonable belief” is interpreted by the OAIC to mean having “a reasonable basis for its belief, and not merely a genuine or subjective belief.”Footnote 53 It indicates that an Australian entity bears the burden of justifying its reasonable belief and suggests that independent legal advice might be one way to do so.Footnote 54

Clause 8.2(a) has three essential components. First, the overseas recipient must be subject to a law or binding scheme. While the law will in most cases be a data protection law, it is also possible that another type of law might impose information handling requirements that offer substantially similar protection.Footnote 55 The “binding scheme” could be “an industry scheme or privacy code that is enforceable once entered into.”Footnote 56 or it could be a set of Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs).Footnote 57 On this point, the OAIC refers to BCR put in place under the EU’s GDPR. If, for example, an Australian entity was part of a group subject to BCR established under the GDPR it could transfer data to other entities in other countries that were subject to the same BCR. In this way, Australian companies can piggy-back on a scheme implemented under the GDPR and subject to the GDPR’s explicit requirements and regulatory oversight.

The second component of clause 8.2(a) is that the law or scheme to which the recipient is bound must be “substantially similar” to Australia’s APPs. According to the OAIC,

A substantially similar law or binding scheme would provide a comparable, or a higher level of privacy protection to that provided by the APPs. Each provision of the law or scheme is not required to correspond directly to an equivalent APP. Rather, the overall effect of the law or scheme is of central importance.Footnote 58

In its Guidance, the OAIC provides examples of relevant factors in assessing substantial similarity. These include the definition of personal information, notification requirements, data quality and security standards, rights of access and correction, and the general way in which collection, use and disclosure of personal information are governed.Footnote 59

The third component of clause 8.2(a) is the requirement that there be mechanisms in place for the individual data subject to enforce privacy provisions. While this could be a complaints process to a regulator, it can also be “an accredited dispute resolution scheme, an independent tribunal or a court with judicial functions and powers.”Footnote 60 A combination of mechanisms can also be acceptable.

Alternatively, subclause 8.2(b) allows for transfers to proceed without need to comply with clause 8.1 where data subjects have provided express consent, following clear notification, to the data transfer taking place without the protection afforded by Principle 8.1. OAIC guidance requires a very clear notice and consent in these circumstances. When it comes to explaining the potential consequences of the transfer taking place without the protection of the APPs, the OAIC requires the individual to be notified that if they consent and the overseas recipient mishandles the information, the Australian entity will not be accountable and the individual will have no recourse under the APA.Footnote 61 If the overseas entity is not subject to any privacy obligations or if redress overseas is not available for the individual, they should also be informed. Further, individuals should be notified if “the overseas recipient is subject to a foreign law that could compel the disclosure of personal information to a third party, such as an overseas authority.”Footnote 62

Subclause 8.2(c) allows for a cross-border data transfer without consent where it is required or authorized under Australian law, where certain statutory exceptions for disclosure apply,Footnote 63 or where the transfer is required or authorized under an international information sharing agreement.Footnote 64

Section 16C of the APA establishes the responsibility of Australian entities that disclose personal information to overseas recipients. It provides that an Australian entity is considered to have breached the APPs where an overseas recipient “does an act, or engages in a practice, in relation to the information that would be a breach of the Australian Privacy Principles [… ] if those Australian Privacy Principles so applied to that act or practice”.Footnote 65 Accountability follows the structure of APP 8.1 and 8.2. Clause 8.1 essentially requires the Australian entity to take reasonable steps, usually in the form of contractual arrangements to ensure that an overseas entity handles the personal data appropriately. An Australian entity that relies upon 8.1 is held accountable for any breaches of the APP by the offshore entity – whether deliberate or inadvertent.Footnote 66

The situation is otherwise if the data transfer has taken place under clause 8.2. The Australian entity is not held liable if they transferred data offshore in the ‘reasonable belief’ that the offshore entity is subject to a law or binding scheme that offers at least substantially similar protection to that available under the APPs. Compliance with 8.2 requires that there be mechanisms in place that allow data subjects to enforce their rights. The Australian entity will also not be held liable if data subjects have provided express consent to a transfer of data without the usual protections. Thus, under the Australian scheme, ‘adequacy’ or its equivalents allow the Australian entity to shift the burden of accountability to the offshore entity.

Australian law deals with law enforcement or national security access by foreign state actors outside of Australia differently than the GDPR. Essentially, subsection 6A(4) of the APA provides that an act in respect of personal information does not breach the APPs if it is done outside of Australia and is “required by an applicable law of a foreign country.” This means that the Australian entity is not accountable if such access takes place. The OAIC, in its Guidance, uses the specific example of the USA PATRIOT ACT.Footnote 67 Further, there is no legislated requirement to notify individuals of the potential for such disclosures, although OAIC guidance suggests that an entity “could consider” providing notification of the risks that such information sharing may be required under foreign law.

The Australian regime is not explicitly organized around whether a particular cross-border data flow is a ‘use’ or a ‘disclosure’; the term ‘disclosure’ is used for all cross-border transfers. Instead, the regime is structured around accountability. Where data is to be disclosed across borders, accountability lies with either the Australian entity that transfers the data or the offshore company, depending on which clause (8.1 or 8.2) applies. Where enforceable contractual arrangements alone are relied upon to protect the personal data, the Australian entity remains accountable for any breach. Where there is a ‘reasonable belief’ that a substantially similar level of protection is available for the personal data, or where the entity has obtained a very clear and precise consent to a transfer without the usual safeguards, the responsibility for any breach will lie with the offshore organization. In practical terms, this would map onto a Canadian-style use/disclosure dichotomy, since ‘uses’ fall within the agency-type arrangement usually dealt with by contracts; whereas a disclosure, which involves a loss of control over the data by the domestic entity because the recipient plans to use the data for their own purposes, will require something different. In this case, that something different must be assurances that the recipient organization is bound by substantially similar data protection obligations that can be enforced by Australian data subjects.

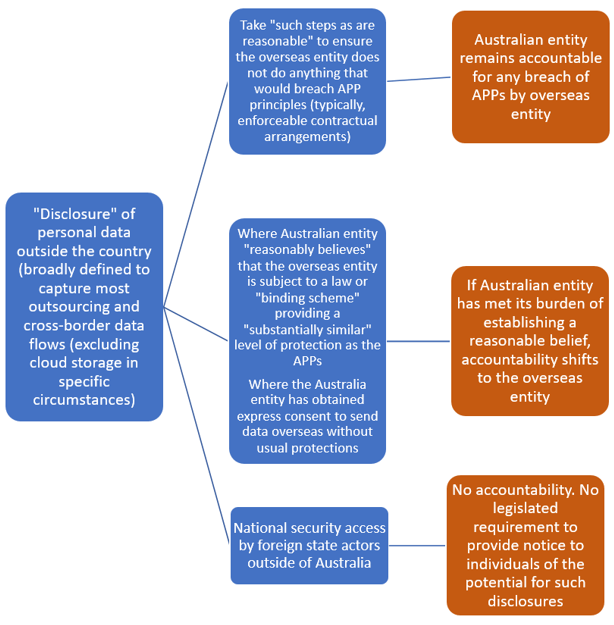

Table I below summarizes how the Australian regime assigns accountability.

Table I: Accountability for Cross-Border Data Flows in Australia

Text version of Table I

Table I: Accountability for Cross-Border Data Flows in Australia

- “Disclosure” of personal data outside the country (broadly defined to capture most outsourcing and cross-border data flows (excluding cloud storage in specific circumstances)

- Take “such steps as are reasonable” to ensure the overseas entity does not do anything that would breach APP principles (typically, enforceable contractual arrangements)

- Australian entity remains accountable for any breach of APPs by overseas entity

- Where Australian entity “reasonably believes” that the overseas entity is subject to a law or "binding scheme" providing a "substantially similar" level of protection as the APPs

Where the Australia entity has obtained express consent to send data overseas without usual protections- If Australian entity has met its burden of establishing a reasonable belief, accountability shifts to the overseas entity

- National security access by foreign state actors outside of Australia

- No accountability. No legislated requirement to provide notice to individuals of the potential for such disclosures

- Take “such steps as are reasonable” to ensure the overseas entity does not do anything that would breach APP principles (typically, enforceable contractual arrangements)

iii. New Zealand

On June 30, 2020, a bill to amend New Zealand’s Privacy Act,Footnote 68 received royal assent, with amendments to take effect on December 1, 2020. Among the changes to the Act are new provisions that will strengthen protection for cross-border data flows. These are described in a Cabinet document as part of a suite of changes “to reflect the needs of the digital age.”Footnote 69 The same report notes that “[p]ublic confidence in cross-border information flows is essential for New Zealand’s effective participation in global markets.”Footnote 70

Prior to the amendments, the legislation contained provisions that governed data that was received in New Zealand from overseas, and that was further transferred abroad. These remain substantially the same in the amended version of the legislation.Footnote 71 Under these provisions, the Commissioner can prohibit the further transfer of overseas personal information outside New Zealand where he or she is satisfied on reasonable grounds that the information will not receive protection comparable to that provided under New Zealand’s Privacy Act in the destination state, and where the transfer “would be likely to lead to a contravention of the basic principles for data protection set out in the OECD Guidelines for the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data.Footnote 72 In addition to the criteria for prohibiting a transfer set out in section 114B(1),Footnote 73 section 114B(2)Footnote 74 directs the Commissioner to take into account other considerations, including whether the transfer might affect any individual, the “desirability of facilitating the free flow of information between New Zealand and other states,” and any international guidelines relating to the free flow of data. These provisions do not apply where the data transfers are required or authorized by law or required by an international convention to which New Zealand is a signatory. The Commissioner is empowered to hold an inquiry into whether a transfer of data should be allowed. A transfer prohibition notice issued by the Commissioner must set out certain details, prescribed in s. 114D,Footnote 75 which include the personal information included in the prohibition, and whether the prohibition is absolute or subject to being lifted if specified steps are taken by the transferor. Any such order is subject to an appeal. Section 114EFootnote 76 allows the Commissioner to vary or cancel a transfer prohibition order should the circumstances warrant it. The law provides for fines against any company that fails to comply with a transfer prohibition notice, although the fine remains capped at a modest $10,000.

Like PIPEDA and the APA, the New Zealand Privacy ActFootnote 77 (NZPA) is organized around the actions of collection, use and disclosure of personal information. However, s. 11 of the NZPA identifies special circumstances where data is transferred from one organization to another without constituting a “disclosure”.Footnote 78 Specifically, if the recipient holds data as an agent for the transferor (e.g. for safe custody or processing) then the data is considered to be held by the transferor and not the recipient.Footnote 79 In such circumstances, neither the flow of data from transferor to recipient, or back again, is considered a use or a disclosure.Footnote 80 The New Zealand Privacy Commissioner has described this provision as applying, for example, in the case of a provider of cloud storage services,Footnote 81 or in cases where data is outsourced for processing.Footnote 82 However, if the recipient uses or discloses the personal information for their own purposes, then the data is considered to have been disclosed by the New Zealand entity. As a Cabinet paper explains, “Once disclosed overseas, the information falls outside the Act’s jurisdiction.”Footnote 83 As a result, a new privacy principle has been introduced which places the onus on the New Zealand organization to ensure that the data will receive an acceptable level of protection in the country of transfer. According to the Cabinet document, “The new privacy principle will give agencies considerable flexibility around what steps they take to ensure the acceptability of privacy standards in relevant foreign countries.”Footnote 84

The reformed New Zealand Privacy Act contains a new Information Privacy Principle (IPP) 12, titled “Disclosure of personal information outside New Zealand” that specifically addresses cross-border data flows.Footnote 85 As noted above, IPP 12 will apply to disclosures of data outside the country. It will not apply where data is outsourced for processing or storage, as long as the recipient is not also using the data for their own purposes. IPP 12 is linked to IPP 11, “Limits on disclosure of personal information.” IPP 11 sets the basic requirements for the disclosure of information, and these must also be complied with for cross-border disclosures. For example, a disclosure must still be consistent with the purposes for which the information was collected and the data subject must have consented to the disclosure. However, IPP 12 permits reliance upon IPP 11 alone for disclosures to a “foreign person or entity” only if certain conditions are met. The first condition is where the data subject has expressly consented to a disclosure in circumstances where the recipient “may not be required to protect the information in a way that, overall, provides comparable safeguards to this Act”. A second possibility is where the recipient, although a foreign company, is carrying on business in New Zealand and the transferor has reasonable grounds to believe that the recipient is subject to the NZ Privacy Act.

In all other cases, Clause 12(1)(c) of IPP 12 permits an overseas disclosure of data where the transferor “believes on reasonable grounds” that the recipient is “subject to privacy laws that, overall, provide comparable safeguards to those in this Act.”Footnote 86 As is the case in Australia, this provision puts the onus on the transferor to assure themselves of the adequacy of another country’s laws. It is not clear what amount of due diligence is required by “reasonable grounds”, nor is it clear how “comparable safeguards” should be assessed. It is anticipated that the Commissioner will provide guidance on these issues.Footnote 87

IPP 12 will also permit disclosures where the NZ organization has “reasonable grounds” to believe that the recipient is participating in a “prescribed binding scheme”. A prescribed binding scheme is one that is specified by regulations.Footnote 88 The regulations will enable the responsible Minister to recommend to the Governor-General that a binding scheme be prescribed, but he or she may only do so where satisfied “that the binding schemes require a foreign person or entity to protect personal information in a way that, overall, provides comparable safeguards” to those in the Act.Footnote 89 The new provisions also allow for the possibility of a made-in-New Zealand adequacy assessment. Clause 12(1)(e) of IPP 12 provides that the transfer may take place if the transferor believes on ‘reasonable grounds’ that the recipient “is subject to privacy laws of a prescribed country.”Footnote 90 A prescribed country is one specified in regulations made under section 214 of the 2020 Act. This provision requires the Minister to consult with the Commissioner in developing regulations for prescribing countries. A country may be prescribed only if the Minister is satisfied that it has “privacy laws that, overall, provide comparable safeguards to those in this Act.Footnote 91 The prescribing of a country may also be limited to a particular type of foreign person or entity to which information may be disclosed, or to the type of information that may be disclosed to a person or entity within that country.Footnote 92

Alternatively, the parties can enter into an agreement, so long as the transferor believes on “reasonable grounds” that the agreement provides “comparable safeguards” to those in the Act.Footnote 93 The New Zealand Privacy Commissioner is planning to publish model contractual clauses that can be used with cross border data transfers.Footnote 94 These clauses will not be mandatory. Instead, the goal is to “create a benchmark for the relevant matters that should be addressed when making sure there are reasonable privacy safeguards when personal information is disclosed overseas.”Footnote 95

Exceptionally, under s. 30 of the NZPA 2020, the Commissioner can authorize a cross-border flow of data that would otherwise contravene IPP 12 in very specific circumstances set out in the legislation. Authorization depends on the Commissioner finding a clear public interest in the disclosure or something that would be of clear benefit to the individual, outweighing any possible harm or detriment.

IPP 12(2) contains an overall exception for cross-border disclosure of personal information for purposes of law enforcement, legal proceedings, or public health or safety in circumstances where it is not practicable for the transferor to comply with the requirements set out in IPP 12(1).

These provisions have yet to take effect, and there is currently no application or interpretation of this new scheme. In its report on the bill, the Cabinet Social Policy Committee noted that the provisions were drafted so as to “give agencies considerable flexibility around what steps they take to ensure the acceptability of privacy standards in relevant foreign countries.”Footnote 96

Under this scheme, New Zealand organizations that outsource data across borders for processing remain accountable for what happens to that data (See Table II below). The data will typically be protected by the terms of the outsourcing agreement and the New Zealand organization can be held to account under the NZPA. By contrast, where information is disclosed outside the country, the organization to which data is disclosed is considered outside the reach of the NZPA. As a result, the New Zealand organization bears the burden of ensuring that ‘comparable safeguards’ are in place. This can include determining that the organization to which data is disclosed is subject to a legal regime that provides comparable safeguards. They can also take the form of a prescribed binding scheme, or an agreement between the parties. Where the New Zealand organization does not take reasonable steps to protect the information as required by the NZPA, it will be liable for any breach committed by the overseas agency. However, if reasonable steps have been taken, it will be exempt from liability.Footnote 97

Although the new scheme is anticipated to increase compliance costs for New Zealand organizations, the Cabinet Social Policy Committee noted that these costs “are mitigated by the exceptions to the principle and the ability of the Commissioner to publish a list of acceptable overseas frameworks.”Footnote 98 The additional costs are also “justified in order to introduce greater protections for individuals.”Footnote 99

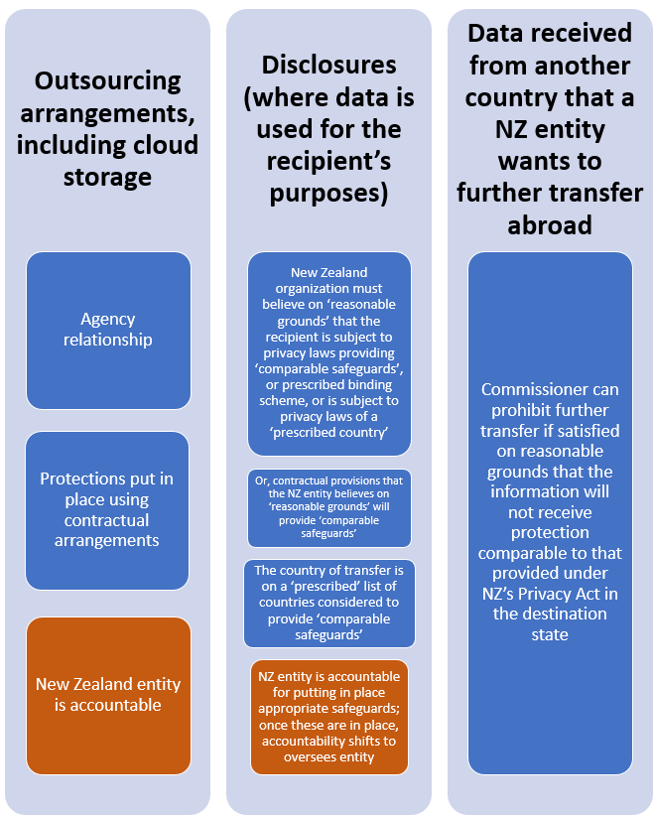

Table II: Allocation of Accountability – New Zealand

Text version of Table II

Table II: Allocation of Accountability – New Zealand

- Outsourcing arrangements, including cloud storage

- Agency relationship

- Protections put in place using contractual arrangements

- New Zealand entity is accountable

- Disclosures (where data is used for the recipient’s purposes)

- New Zealand organization must believe on ‘reasonable grounds’ that the recipient is subject to privacy laws providing ‘comparable safeguards’, or prescribed binding scheme, or is subject to privacy laws of a ‘prescribed country’

- Or, contractual provisions that the NZ entity believes on ‘reasonable grounds’ will provide ‘comparable safeguards’

- The country of transfer is on a ‘prescribed’ list of countries considered to provide ‘comparable safeguards’

- NZ entity is accountable for putting in place appropriate safeguards; once these are in place, accountability shifts to oversees entity

- Data received from another country that a NZ entity wants to further transfer abroad

- Commissioner can prohibit further transfer if satisfied on reasonable grounds that the information will not receive protection comparable to that provided under NZ’s Privacy Act in the destination state

iv. Quebec

Quebec’s Bill 64Footnote 100 contains provisions that would specifically amend its private sector data protection lawFootnote 101 as regards cross border data flows. In the case of Bill 64, the borders in question are those of the province of Quebec. This means that data flows from Quebec to other provinces in Canada – as well as outside the country – will be captured by the new provisions.

If Bill 64 is enacted, a new s. 17Footnote 102 would apply where a Quebec entity ‘communicates’ information outside provincial boundaries. While the focus on this new provision appears to be on ‘communications’ (disclosures) of data, s. 17 also provides that it will also apply where a Quebec entity “entrusts a person or body outside Quebec with the task of collecting, using, communicating or keeping such information on its behalf.” The scope of this provision is potentially quite broad. Unlike New Zealand, where the cross-border provisions apply only outside of agency relationships, s. 17 seems to specifically include agency relationships where the recipient of the data is outside of Quebec.Footnote 103 In addition, not only would it seem to include offshore cloud storage of data, it might capture other uses of digital services. For example, if a police service in Quebec contracts with a US-based provider for facial recognition services that rely upon the provider’s US-based database of images, are they entrusting this company to collect, use and communicate information on its behalf? If so, the organization could not use this service unless there is an agreement in place that meets the requirements of s. 17.

According to Bill 64, the legitimacy of a proposed cross-border flow will depend on a number of factors which include: an assessment of the degree of sensitivity of the personal information, the purposes for which it will be used, the protection measures that will apply to it, and the legal framework in place in the jurisdiction to which the transfer will take place.Footnote 104 The collection, use or communication can only take place if an assessment of these factors establishes that the personal information “would receive protection equivalent to that afforded under this Act.”Footnote 105 There must also be a written agreement that governs the activities in relation to data; that refers to the assessment made; and that, where appropriate, contains “terms agreed on to mitigate the risks identified in the assessment.”Footnote 106 Nothing in the bill suggests that these assessments must be approved by the Commission d’accès à l’information or some other body before data can flow across borders, nor is there a requirement for assessments to be filed with the Commission.

Under the proposed s. 17(4), an organization must assess “the legal framework applicable in the State in which the information would be communicated, including the legal framework’s degree of equivalency with the personal information protection principles applicable in Quebec.” This is a challenging task for an organization, which presumably might have to seek legal opinions on foreign law. A proposed s. 17.1 foresees the potential for the involvement of the Quebec government in carrying out assessments of the adequacy of foreign regimes. It provides that the Minister shall publish in the Official Gazette “a list of States whose legal framework governing personal information is equivalent to the personal information protection principles applicable in Quebec.”Footnote 107

The proposed system in Bill 64 (see Table III below) seems premised on a finding of equivalency that is made either by the government, or that is based on assessments carried out by those seeking to transfer data across borders. Unlike New Zealand, no distinction is made between processing activities where there is an agency relationship and activities that amount to disclosures. Unlike the schemes in the EU, Australia or New Zealand, there are no other alternatives provided (such as SCCs, BCR, or contracts) that could be leveraged to provide an equivalent level of protection even if it is absent at the state level. However, s. 17 seems to provide some wiggle room in that written agreements may contain “terms agreed on to mitigate the risks identified in the assessment.”

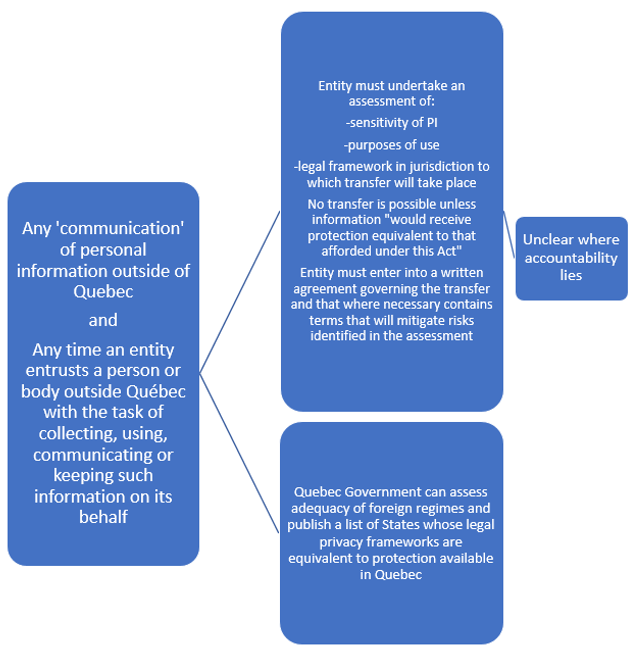

Table III – Overview of Quebec Framework

Text version of Table III

Table III – Overview of Quebec Framework

- Any ‘communication’ of personal information outside of Quebec

and

Any time an entity entrusts a person or body outside Quebec with the task of collecting, using, communicating or keeping such information on its behalf- Entity must undertake an assessment of:

- sensitivity of PI

- purposes of use

- legal framework in jurisdiction to which transfer will take place

Entity must enter into a written agreement governing the transfer and that where necessary contains terms that will mitigate risks identified in the assessment- Unclear where accountability lies

- Quebec Government can assess adequacy of foreign regimes and publish a list of States whose legal privacy frameworks are equivalent to protection available in Quebec

- Entity must undertake an assessment of:

v. Convention 108+

The Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal DataFootnote 108 (Convention 108) is a Council of Europe Treaty that was opened for signature in 1981 and that was the first legally binding international data protection instrument. It addresses data protection in both public and private sector contexts. It entered into force in 1985 with five ratifications. It has since been signed and ratified by a total of forty-seven European countries and has been ratified by an additional eight countries outside of Europe.Footnote 109 Canada has observer status with the Council of Europe in relation to this treaty.Footnote 110 Convention 108+ has been described as “the only legally binding multilateral instrument on the protection of privacy and personal data open to any country in the world.”Footnote 111

In 2018, Convention 108 was amended to create the Modernised Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal DataFootnote 112 (Convention 108+). To date, this revision has been signed and ratified by seven European nations, and signed by a further thirty-five, including three non-European countries. Convention 108+ is particularly notable in that it upgrades the rules relating to cross-border data transfers.Footnote 113 According to Graham Greenleaf, the rules in Convention 108 were unlikely to meet the threshold for GDPR adequacy, but Convention 108+ upgrades the data protection norms to be more in line with the GDPR.Footnote 114 Greenleaf notes that Recital 105 of the GDPR indicates that accession to Convention 108 is a factor to take into account in an adequacy assessment,Footnote 115 although it is not determinative. The upgraded requirements of Convention 108+ increase the likelihood that accession to this convention could go a long way to satisfying a GDPR adequacy assessment. In his view, “Accessions to 108+ coupled with proper enforcement, should ensure that most of the GDPR requirements are met.”Footnote 116

Meeting GDPR adequacy requirements is a key element in ensuring the free flow of data across borders between Canada and EU countries since this is the easiest and most straightforward option to facilitate cross-border data flows. As a general principle, article 14 of Convention 108+ provides that data can flow freely between two countries that are party to Convention 108+ unless “there is a real and serious risk that the transfer to another Party, or from that other Party to a non-Party, would lead to circumventing the provisions of the Convention.”Footnote 117 Transfers may also be permitted if “bound by harmonized rules of protection shared by states belonging to a regional international organization.”Footnote 118 This would, of course, include those states bound by the GDPR. For countries outside the EU, a GDPR adequacy assessment is still of value even with accession to Convention 108+, since Convention 108+ does not guarantee adequacy under the GDPR, and Convention 108+ contains exceptions to the principle of free flow of data among parties where a “serious risk” is identified.Footnote 119 However, as Greenleaf suggests, an adequacy assessment would be considerably facilitated by being party to Convention 108+. To the extent that other countries accede to Convention 108+, this framework provides for adequacy to be presumed with respect to other states party to the treaty.

Where the recipient of data is not subject to the jurisdiction of a state party to Convention 108+, then art. 14(2) provides that the transfer can only take place if “an appropriate level of protection based on the provisions of this Convention” is secured. This can be done by an assessment of the adequacy of the laws of the state where the recipient is located;Footnote 120 by ad hoc contractual arrangements or by approved “standardized safeguards provided by legally-binding and enforceable instruments” (SCCs);Footnote 121 or by consent by a data subject to the transfer with explicit notice of the risks and the lack of appropriate safeguards.Footnote 122 According to the Council of Europe, transfers of data must be assessed based on

Various elements of the transfer should be examined such as: the type of data; the purposes and duration of processing for which the data are transferred; the respect of the rule of law by the country of final destination; the general and sectoral legal rules applicable in the State or organisation in question; and the professional and security rules which apply there.Footnote 123

Transfers may also take place without appropriate safeguards if the “specific interests of the data subject require it in the particular case”, or if there are important prevailing interests such as the public interest and the transfer “constitutes a necessary and proportionate measure in a democratic society”.Footnote 124

Convention 108+ also specifies that the competent supervisory authority must be “provided with all relevant information concerning the transfers of data” that take place under contractual arrangements, whether these are under ad hoc or approved standardized safeguards.Footnote 125 In addition, the supervisory authority should be “entitled to request that the person who transfers data demonstrates the effectiveness of the safeguards or the existence of prevailing legitimate interests.”Footnote 126 Further, the supervisory authority should be able to prohibit or suspend transfers or place conditions on them in order to “protect the rights and fundamental freedoms of data subjects.”Footnote 127 These oversight powers are important, particularly if amendments to PIPEDA are made with a view to becoming a party to Convention 108+ in the future.

Convention 108+ offers an intriguing option for developing an international consensus around data protection norms with some teeth (as opposed to more general guidance such as the OECD or the APEC principles). In Canada, Colin Bennett has suggested that Convention 108+ may provide a partial solution to the challenges faced by Canada when it comes to cross-border data transfers since it has the potential to support a finding of adequacy with countries bound by the GDPR as well as with other signatories.Footnote 128 Greenleaf is also an advocate of accession to Convention 108+ as a means of building a global consensus around data protection. He describes it as providing the “only realistic long-term prospects of a global data privacy agreement.”Footnote 129

However, while accession to Convention 108+ might have some longer-term advantages for Canada, it is not a short-term solution. PIPEDA and the Privacy ActFootnote 130 would require amendment for both adequacy under the GDPR and for accession to Convention 108+. Provincial buy-in would also be required, since amendments to provincial data protection laws would most likely also be needed. A considerable amount of federal/provincial co-operation and co-ordination might be required, although this may ultimately not be so different from what will be necessary to meet an GDPR adequacy assessment. With that in mind, preparation for a GDPR adequacy assessment could be aligned with putting in place the measures necessary to accede to Convention 108+. Being a state party to this convention would make it easier to create a list of countries to which Canadian companies can disclose data.

- Date modified: