Public opinion survey

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Canadian Businesses and Privacy-Related Issues

Final Report

Prepared for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Phoenix SPI

February 2012

Executive Summary

Phoenix SPI was commissioned by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) to conduct quantitative research with Canadian businesses on privacy-related issues. The purpose was to better understand the extent to which businesses are familiar with privacy issues and requirements, and the types of privacy policies and practices that they have in place. A 16-minute telephone survey was administered to 1,006 companies across Canada, stratified by size of business. The results were weighted by size, sector and region using Statistics Canada data to ensure that they reflect the actual distribution of businesses in Canada. Data collection was conducted December 2-19, 2011. Based on a sample of this size, the results can be considered accurate to within ±3.1%, 19 times out of 20. Results are compared to similar surveys conducted in 2007 and 2010 where relevant. The 2011 survey includes updates and additions to the questionnaire and survey approach to better address the current, evolving privacy environment and cannot, in some cases, be compared with the results of previous waves of the survey.

Privacy Practices

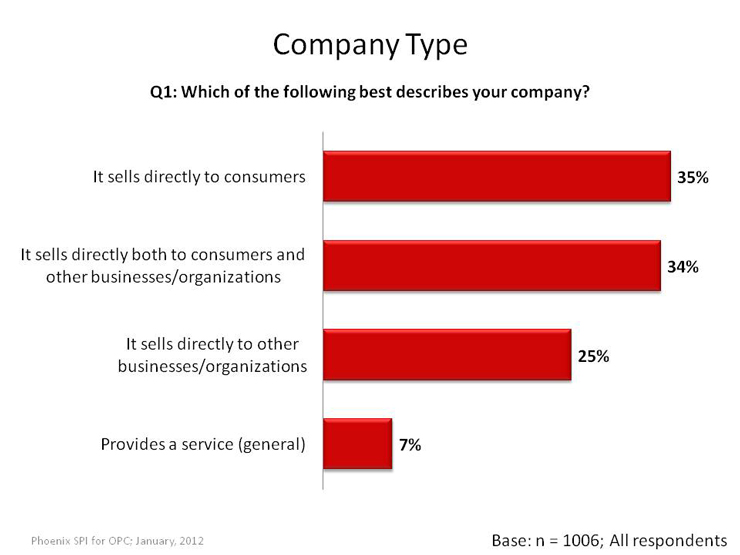

A variety of business 'types' were included in this survey in terms of their target consumer. Thirty-five percent of the companies sell directly to the general public (or subsets of it), while almost as many (34%) sell both to the public and to other businesses/organizations. Almost one quarter (24%) sell only to other businesses/organizations, while 7% provide services that do not fall into any of these categories.

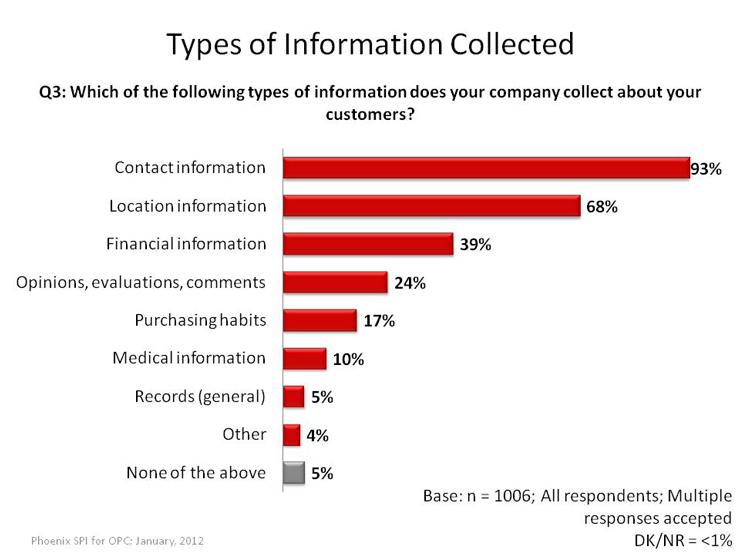

In terms of the types of information collected about customers, the vast majority (93%) collect contact information, such as names, phone numbers, and addresses. More than two thirds (68%) collect location information (e.g. postal codes). Other types of information collected in significant numbers include financial information (39%), opinions, evaluations, and comments (24%), purchasing habits (17%), and medical information (10%). Five percent said they do not collect any of these types of customer information.

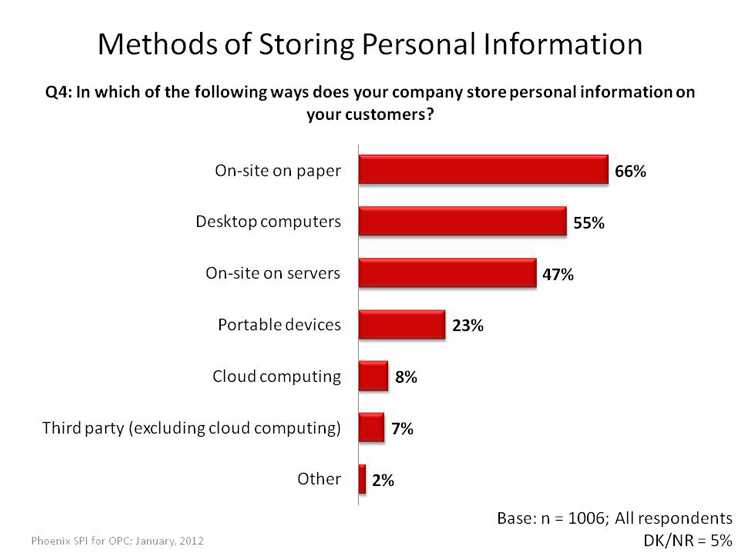

Two thirds (66%) of businesses store their customers' personal information on paper records kept on site. As well, 55% store personal information on desktop computers and 47% use on-site servers. Nearly one quarter (23%) use portable devices (e.g. laptops, USB sticks, or tablets), while smaller proportions use cloud computing (8%) and a third party (excluding cloud computing) (7%). Of those firms that use portable devices to store customers’ personal information, 44% use encryption to protect such information.

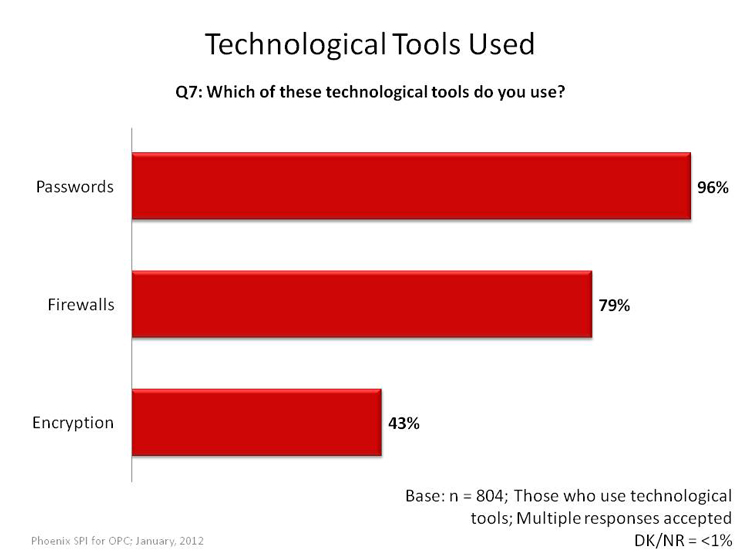

Canadian businesses use a number of methods to protect the personal information of their customers. Almost three quarters use technological tools, such as passwords, encryption, or firewalls (73%), or physical measures, such as locked filing cabinets, restricting access, or security alarms (72%). About half (51%) use organizational controls, such as policies and procedures. Of those that use technological tools to protect the information, fully 96% use passwords, while 79% use firewalls, and 43% use encryption.

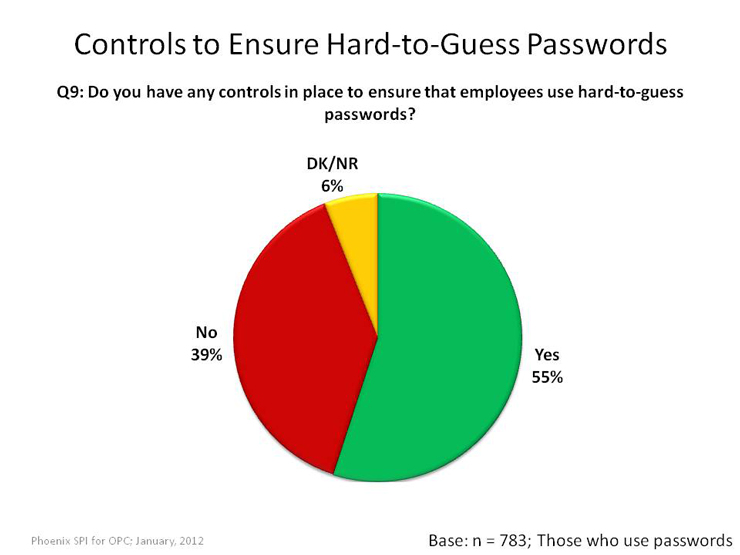

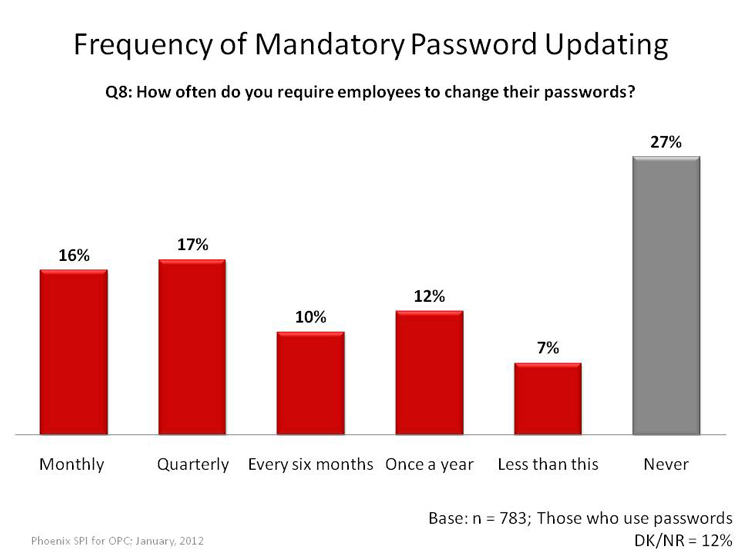

A majority of firms that use passwords (55%) have controls in place to ensure employees use hard-to-guess passwords. Also, most require employees to change their passwords: 16% require this monthly, 17% quarterly, 10% every six months, 12% yearly, and 7% less than this. Twenty-seven percent do not require employees to change their passwords.

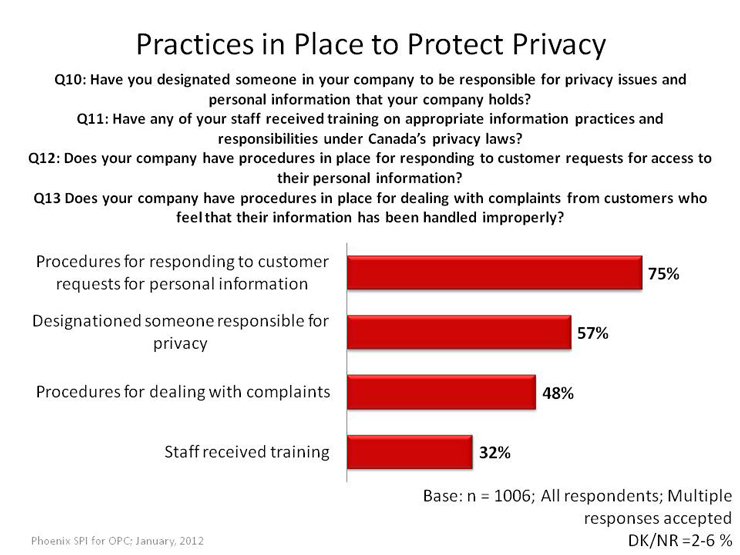

Businesses have in place a mix of mechanisms related to privacy. The mechanism that is most widely used, cited by three quarters, is procedures for responding to customer requests for personal information. This is followed, at a distance, by designating someone responsible for privacy (57%). Almost half (48%) have procedures for dealing with customer complaints, while 32% ensure that their staff receive privacy-related training.

Privacy Policy

In total, 62% of businesses have a privacy policy. Executives of companies that do not have a privacy policy were asked why not. The main reason was a perceived lack of need (45%). Other explanations offered with some frequency include the size of the company (being too small) (17%), that the company does not collect personal information on customers (14%), and that they have never thought about it (10%).

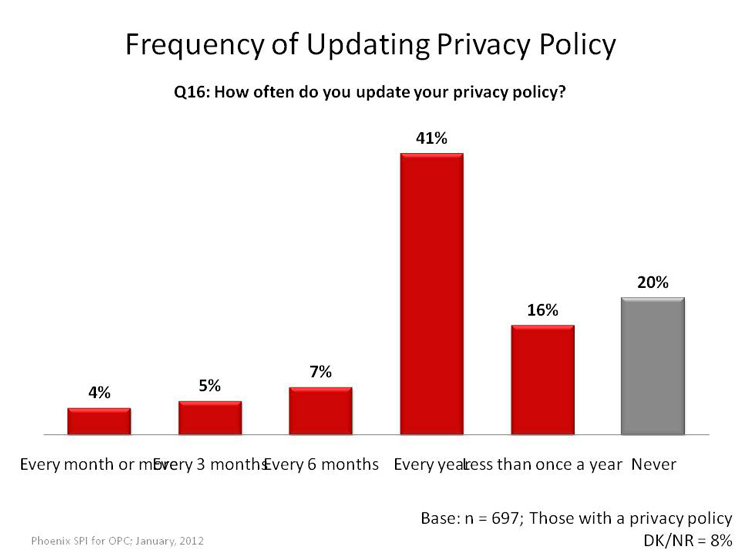

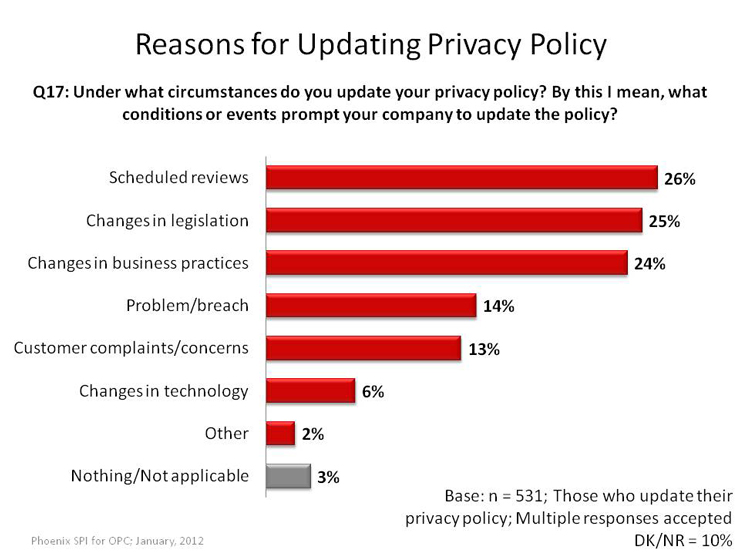

Most companies that have a privacy policy update their policy (57%) at least once a year: 4% do so monthly, 5% every three months, 7% every six months, and 41% every year. Sixteen percent update their policy less than yearly, while 20% have never updated their policy. Executives of firms that update their privacy policy were asked under what circumstances they do so. Roughly one quarter mentioned each of the following: scheduled reviews (26%), changes in privacy legislation (25%), and changes in business practices (24%). Significant numbers also identified the occurrence of a problem or breach of privacy (14%), and customer complaints or concerns (13%). Six percent pointed to changes in the technology used by the company.

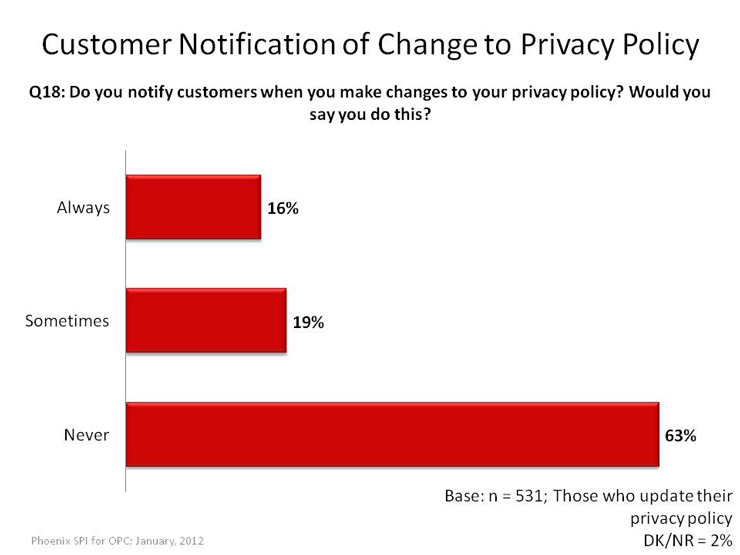

Most of the companies that update their privacy policy (63%) do not notify their customers about related changes. Conversely, just over one third (35%) do notify customers when changes are made to the policy – 16% do this always, while 19% do so sometimes.

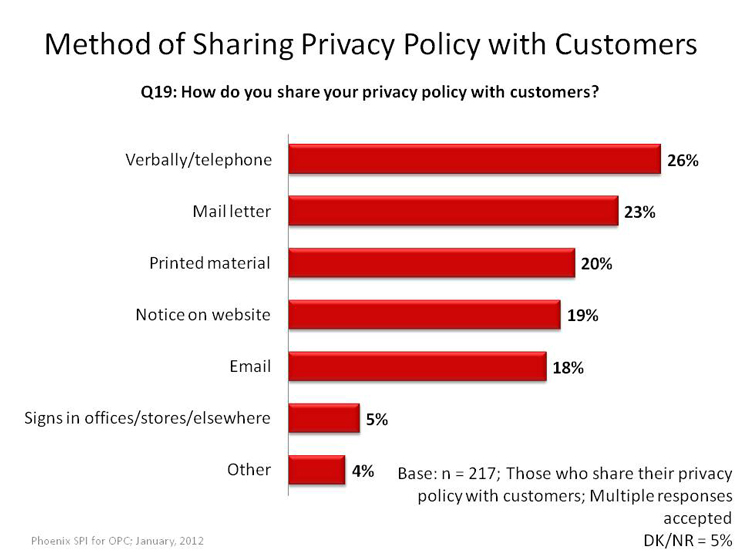

Businesses that share their privacy policy do so in a variety of ways, with no method dominating. The largest proportion (26%) do this verbally, or over the telephone, followed relatively closely by mailing a letter (23%), using printed materials, such as pamphlets and brochures (20%), placing a notice on their company’s website (19%), and emailing customers (18%). Five percent use signs in their offices, stores or other locations.

Privacy as Corporate Objective

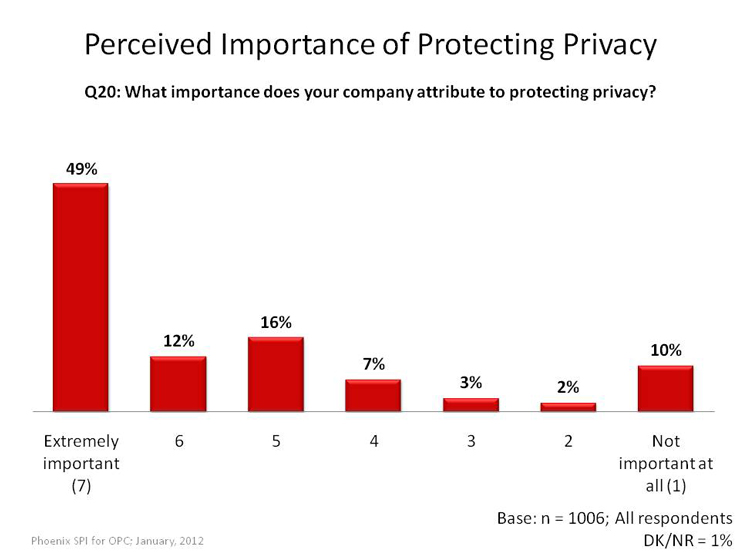

When asked to rate the importance their company attributes to protecting privacy (using a 7-point scale), almost half (49%) rated this as extremely important, while a further 28% rated it as at least moderately important. In total, therefore, 77% of Canadian companies attribute considerable importance to protecting privacy. Conversely, 15% attribute relatively little importance to this, offering scores below the mid-point on the scale.

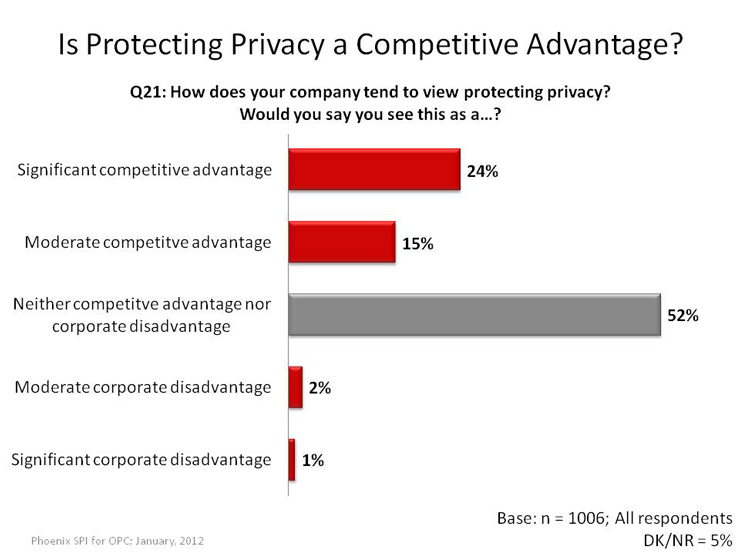

When asked how their company tends to view protecting privacy, 52% said they see it as neither a competitive advantage nor a corporate disadvantage. That said, 39% do view it as a competitive advantage, with 24% seeing it as a significant advantage and 15% a moderate advantage. Few (3%) view protecting privacy as a corporate disadvantage.

Awareness and Impact of Privacy Laws

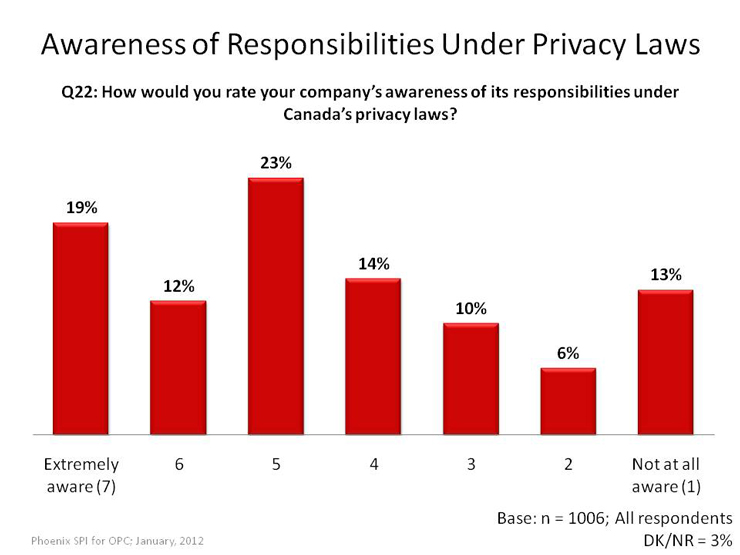

Executives were asked to rate their company’s awareness of its responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws (using a 7-point scale). In response, 19% think their firm is extremely aware of its responsibilities, while a further 35% claimed high awareness (scores of 5-6). In total, a slight majority (54%) offered positive scores above the mid-point on the scale, indicating a relatively high level of familiarity with their privacy responsibilities. At the other end of the spectrum, 29% offered scores below the mid-point of the scale, suggesting a relatively low level of awareness.

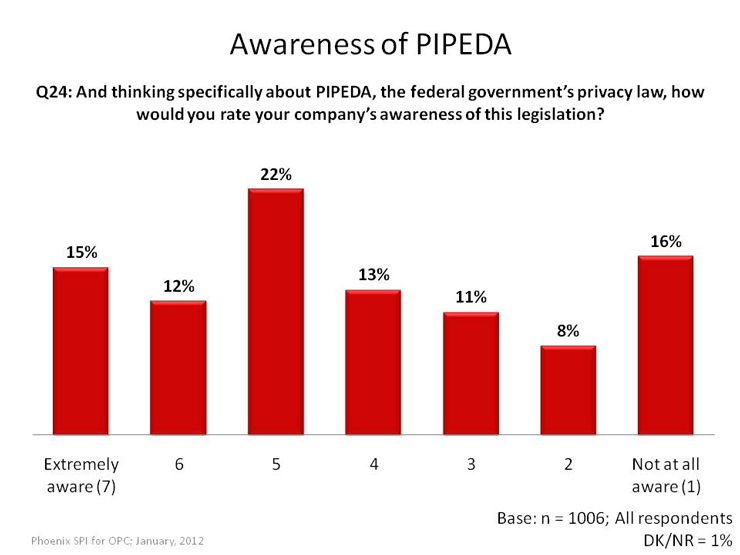

Similarly, executives were asked to rate their level of awareness of PIPEDA, the federal private sector privacy law, using the same scale. The results were roughly similar. Fifteen percent said they were extremely aware of the legislation, while 34% offered scores of five or six. Therefore, almost half (49%) offered positive scores on the scale, once again indicating a relatively high level of familiarity with their responsibilities (35% offered scores below the scale's mid-point). Awareness of PIPEDA specifically is therefore slightly lower than awareness of responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws more generally.

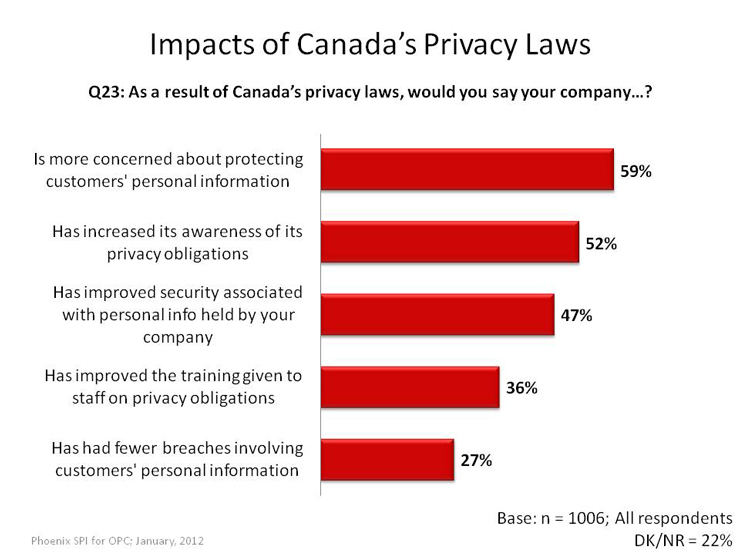

Canada’s privacy laws have resulted in a range of impacts on Canadian businesses. For 59%, such legislation has increased the level of concern in the company about protecting customers’ personal information. A smaller majority (52%) think these laws have increased their company’s awareness of its privacy obligations, while 47% point to improved security for personal information held by their company. In addition, 36% have improved the training given to staff on privacy obligations, and 27% have had fewer breaches involving customers’ personal information.

Compliance, Breaches and Risk Assessment

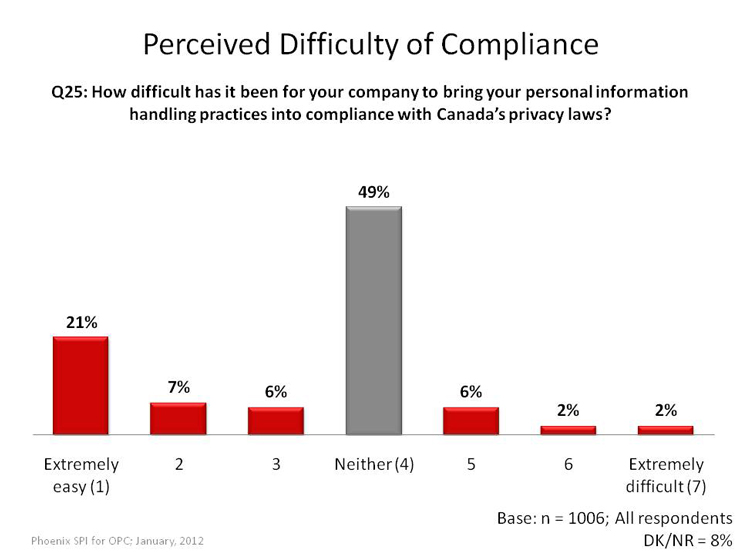

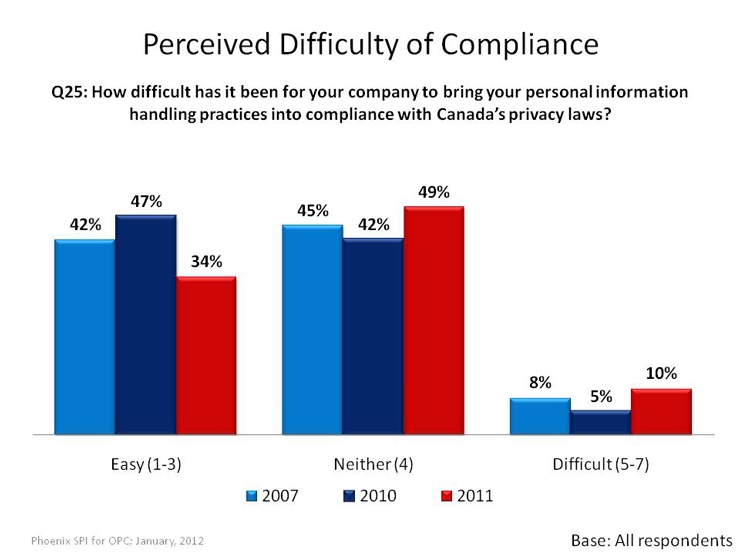

Executives were asked how difficult it has been for their company to bring their personal information handling practices into compliance with Canada’s privacy laws. Almost half (49%) were neutral, viewing this as neither easy nor difficult. Most of the rest (34%) rated compliance with privacy laws as easy, while 10% felt that this was difficult for their firm.

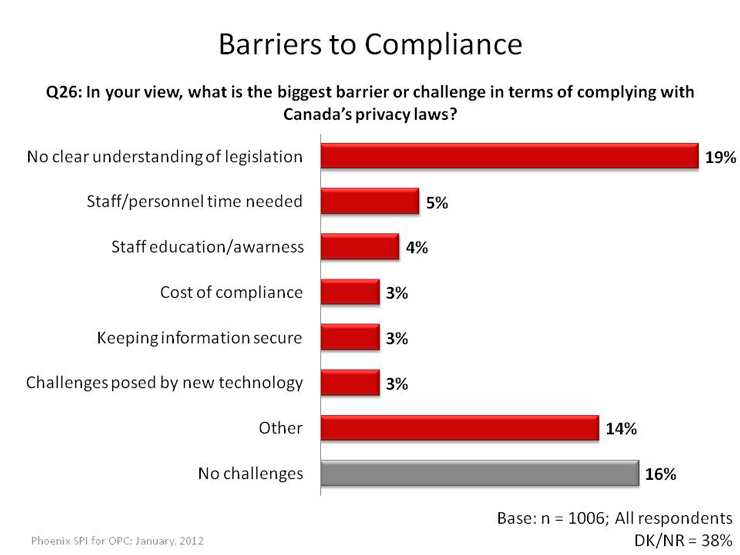

A lack of understanding of privacy legislation was identified most often (19%) as the top barrier or challenge in terms of complying with Canada’s privacy laws. Five percent or less cited a number of other barriers: staff/personnel requirements (5%), staff education/ awareness (4%), cost of compliance (other than staff) (3%), difficulties keeping personal information secure (3%), and challenges posed by new technology (3%). Sixteen percent did not think there were any challenges to compliance, while 38% offered no response.

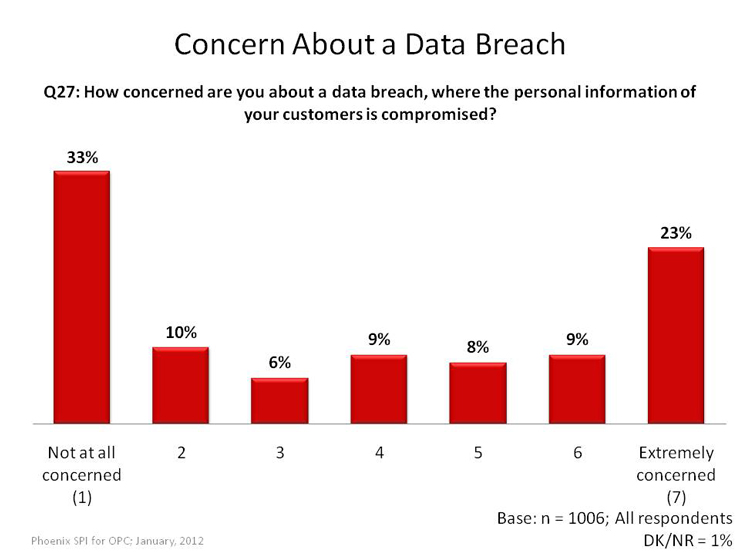

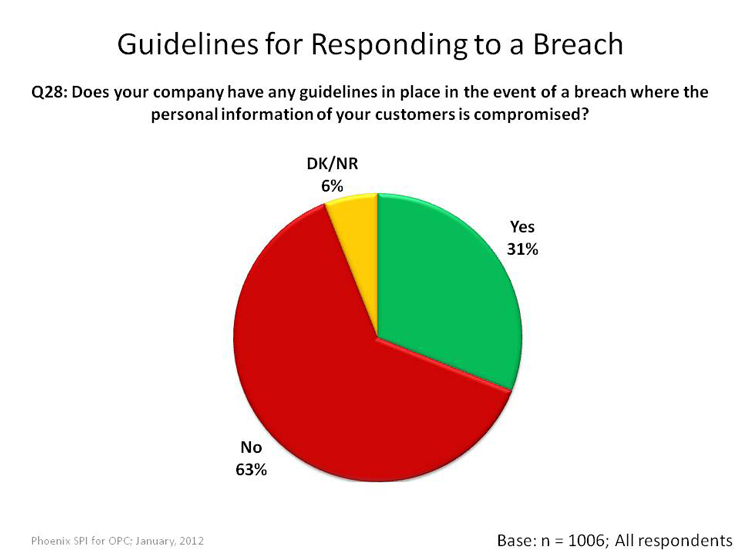

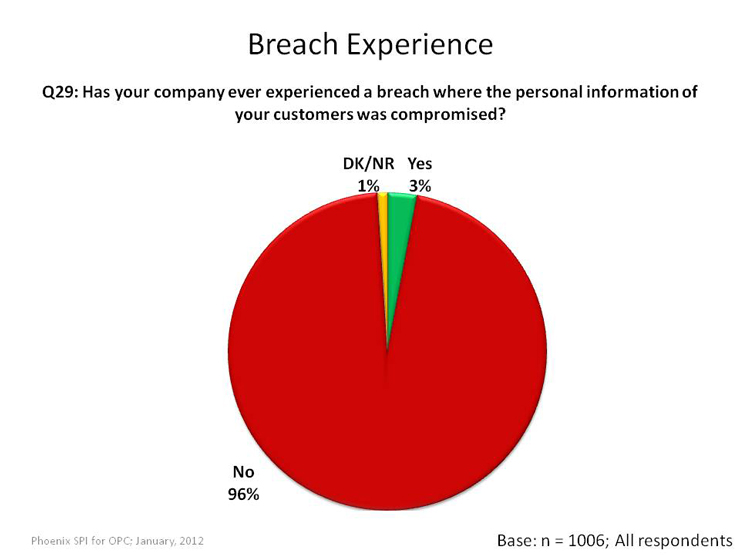

When asked to rate their level of concern about a data breach where personal information is compromised, 40% offered scores above the mid-point of the 7-point scale, suggesting significant concern about a data breach. Thirty-one percent of surveyed companies have guidelines in place in the event of a breach. The vast majority (96%) of businesses have never experienced a breach where customers' personal information was compromised.

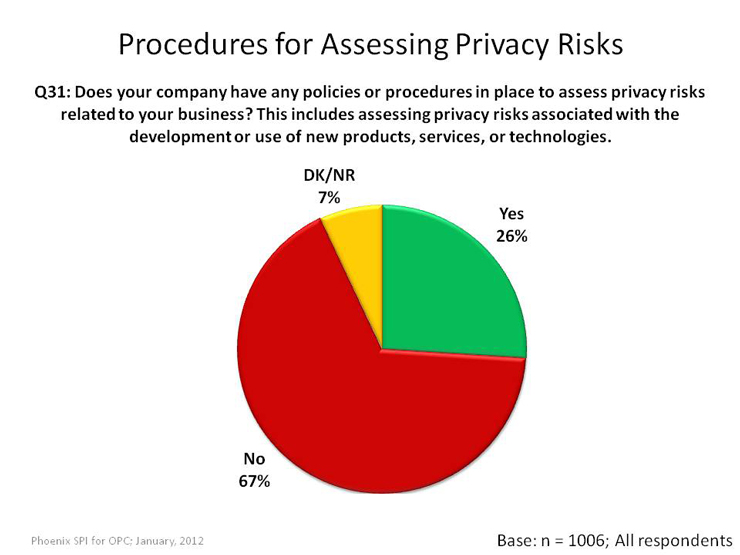

Approximately one quarter (26%) of businesses have policies or procedures in place to assess privacy risks related to their business. This includes assessing privacy risks associated with the development or use of new products or technologies.

Third Parties

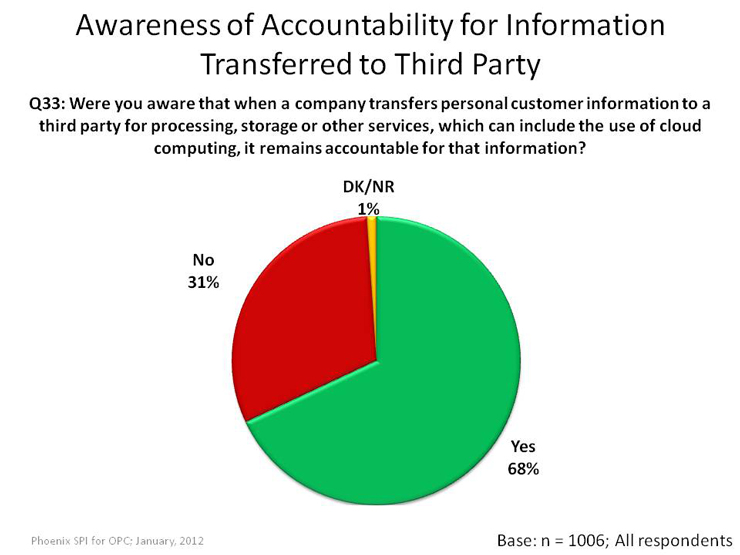

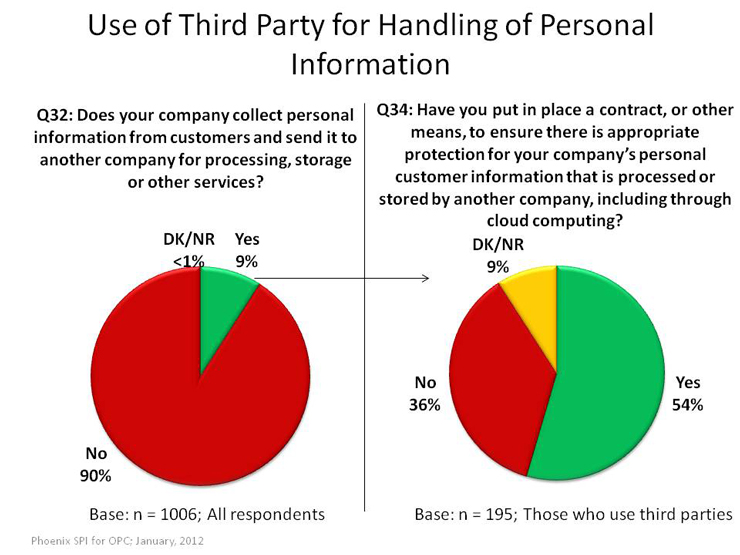

Approximately two thirds (68%) claimed to be aware that when a company transfers personal information to a third party for processing, storage or other services, it remains accountable for that information (this can include the use of cloud computing). Only 9% of businesses collect personal information from customers and send it to another company for processing, storage or other services, and just over half (54%) of these firms have a contract, or some other means, in place to ensure there is appropriate protection for their company’s personal customer information.

Cooperation with Law Enforcement and Government

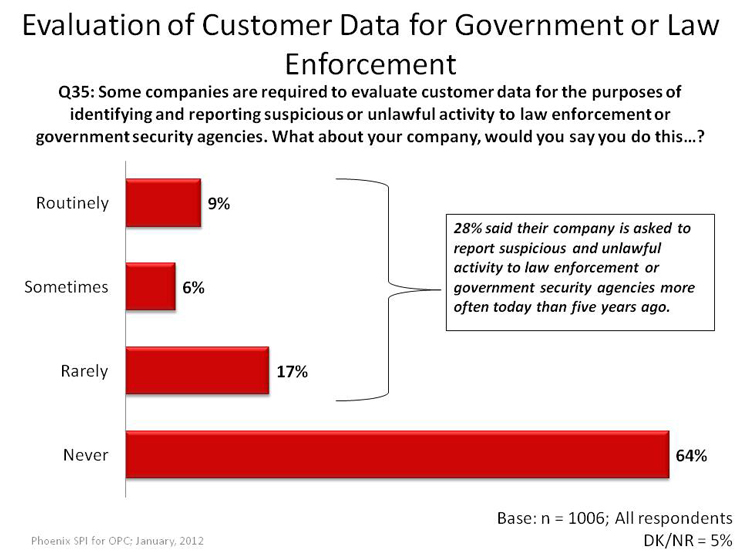

Almost one third of businesses evaluate customer data for the purposes of identifying and reporting suspicious or unlawful activity to law enforcement or government security agencies. Nine percent do this routinely, 6% do this sometimes, and 17% do this rarely. Of the companies that evaluate customer data for this purpose, 28% said their company is asked to do this more often today than five years ago.

Communications

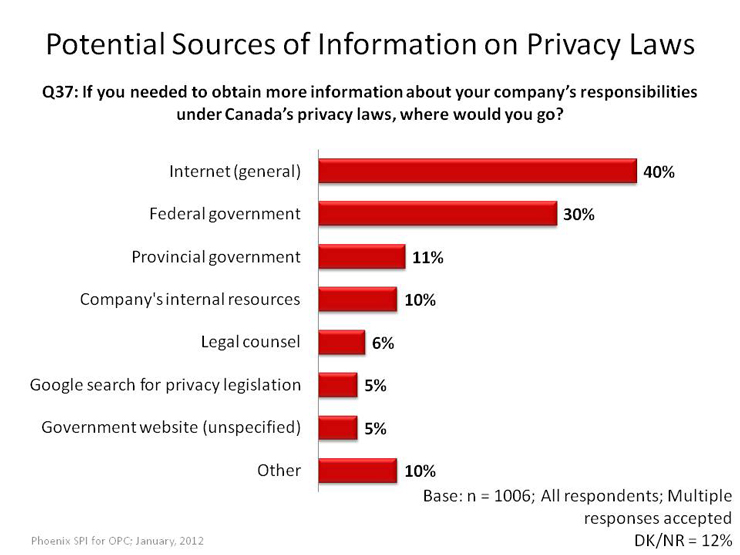

The Internet (40%) is the main place that executives would go if they needed information about their company’s responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws (an additional 5% identified Google specifically). Following this, 30% would turn to the federal government. Other sources mentioned with some frequency include provincial governments (11%), the company’s internal resources (10%), and legal counsel (6%).

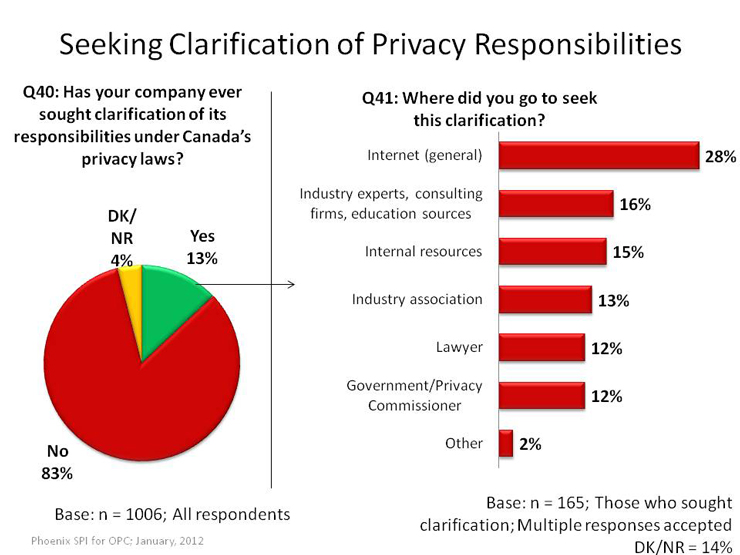

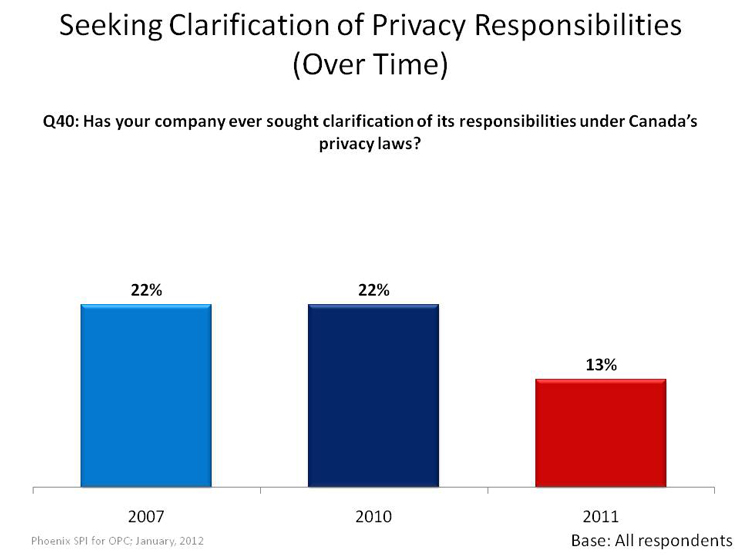

Only 13% of surveyed businesses have ever sought clarification of their privacy-related responsibilities. Of those that did, the top go-to source was the Internet (28%). Other top sources include industry experts, consulting firms, and education sources (16%), a firm's internal resources (15%), industry associations (13%), lawyers (12%), and government, including the privacy commissioner (12%).

Education and Training

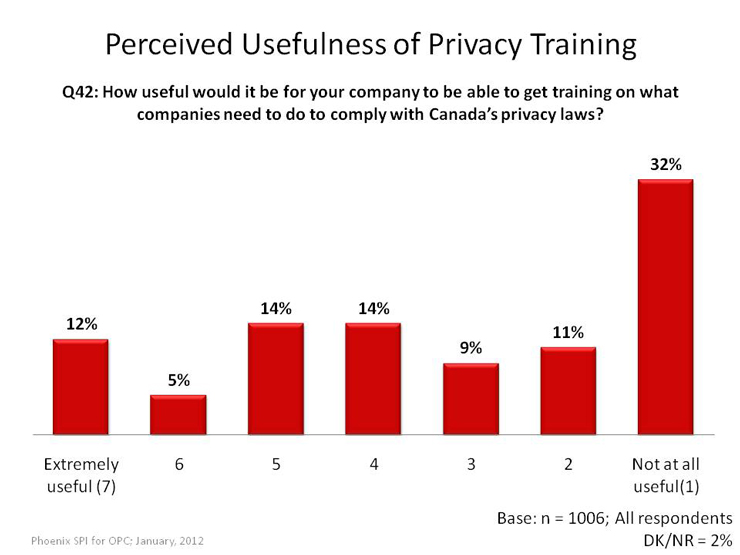

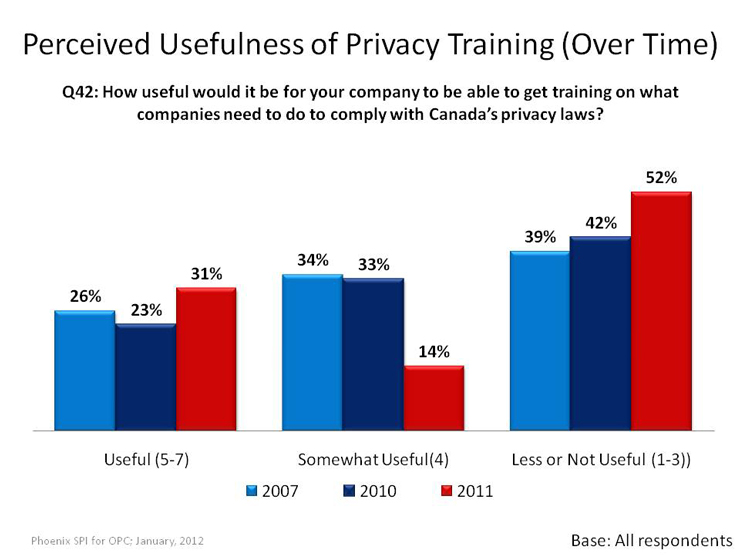

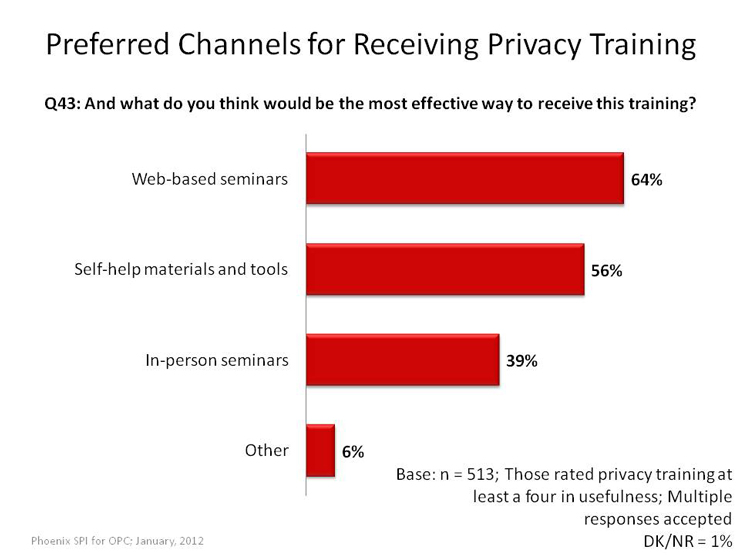

Executives were asked to assess the usefulness of training on what companies need to do to comply with Canada’s privacy laws. In total, 31% rated the usefulness of such training positively, compared with 52% who rated it negatively. Executives who rated privacy training as at least moderately useful for their company were asked to identify the most effective way to receive this training. Almost two thirds (64%) pointed to web-based seminars, followed by 56% who mentioned self-help materials and tools. A strong minority (39%) identified in-person seminars in different cities.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

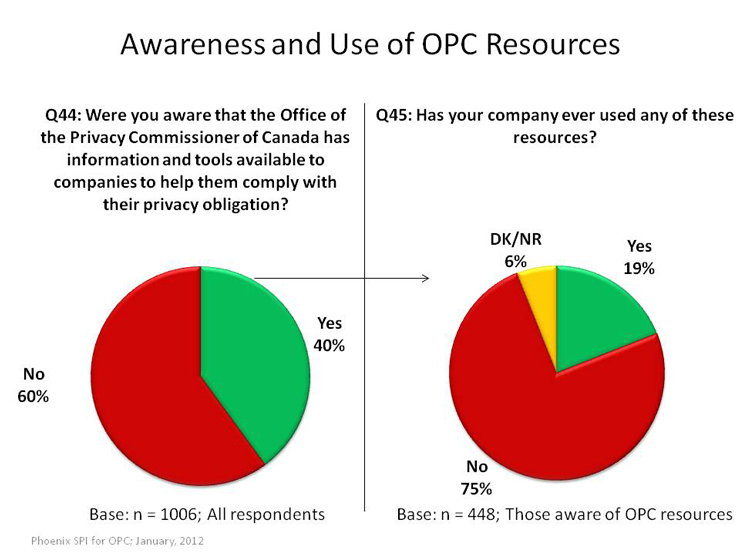

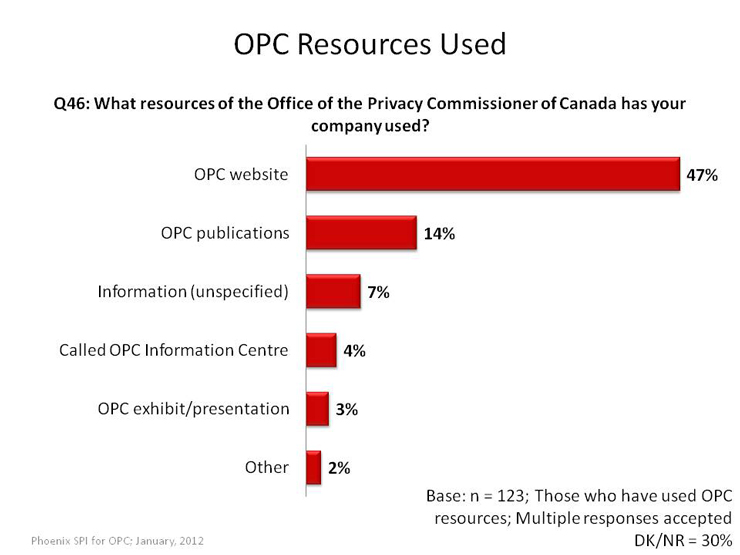

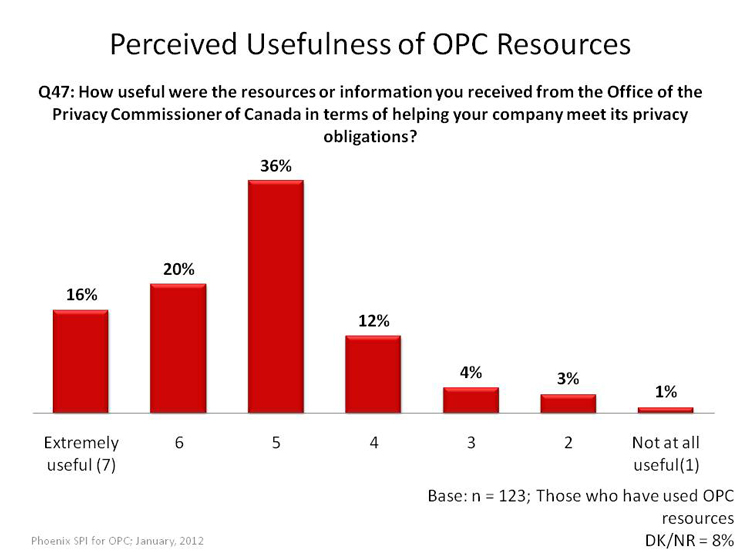

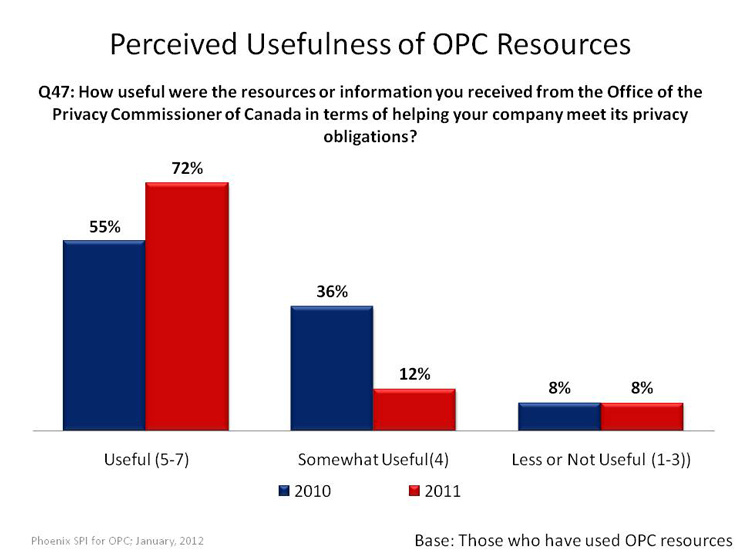

Forty percent of surveyed executives said they were aware that the OPC has information and tools available to companies to help them comply with their privacy obligations. Of those who were aware, 19% said their company has used OPC resources. By far, the most used resource was the OPC website, identified by almost half (47%) of those companies that have used OPC resources. Other resources that were used include OPC publications (14%), general information (7%), the OPC information centre (4%), and an OPC exhibit or presentation (3%). When asked to rate these resources in terms of how useful they were in helping the company meet its privacy obligations, 72% offered positive scores, indicating their view that these resources were at least moderately useful (16% said they were extremely useful). Relatively few (8%) rated the tools as not useful.

Privacy-Related Subgroup Differences

A major distinguishing factor in terms of how businesses address privacy-related issues is company size.Footnote 1 Larger companies are more likely to collect information on their customers, to use various technological, physical, and organizational controls to protect that information, to seek out information about their privacy responsibilities, and to think privacy training would be helpful. In terms of the OPC, larger companies were more likely to be aware that the OPC has resources available to help them with privacy-related issues and to have used these resources. Even so, larger companies were more likely than smaller ones to identify internal resources and legal counsel as sources of privacy information. These tendencies suggest that smaller companies may be most in need of the OPC’s resources (given a lack of internal alternatives), but are least aware of them. That said, smaller companies attributed less importance to protecting privacy than did larger ones. Other factors that significantly aligned with a greater tendency of a company to collect personal information, to have mechanisms to protect that information, and to enhance knowledge about privacy issues through various means included industry type and the number of different locations the company has.

In terms of attitudes and perspectives towards privacy issues, companies that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important are relatively aware of their privacy obligations, perceive compliance with privacy laws to be difficult, and are relatively concerned about data breaches were more likely to collect personal information on their customers, to have in place policies and procedures for protecting the personal information in their possession, and to inform themselves of their privacy obligations.

Introduction

Phoenix Strategic Perspectives Inc. (Phoenix) was commissioned by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) to conduct quantitative research with Canadian businesses on privacy-related issues.

Background and Objectives

The OPC is an advocate for the privacy rights of Canadians with the powers to investigate complaints and conduct audits under two federal laws, publish information about personal information-handling practices in the public and private sectors, and conduct research into privacy issues. As part of this mandate, the OPC is responsible for enforcing the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), which applies to commercial activities in the Atlantic provinces, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and the Territories. Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia each has its own law covering the private sector. Even in these provinces, PIPEDA continues to apply to the federally-regulated private sector and to personal information in interprovincial and international transactions.

Given the rapid rate of technological innovation and the disintegration of borders, issues of privacy are evolving and becoming of greater importance and complexity. In December 2010, Parliament passed amendments to PIPEDA so as to become more responsive to this evolution. In September, Parliament reintroduced further amendments to the Act.

Against this backdrop, there is a need for the OPC to better understand the following with respect to Canadian businesses in their dealing with privacy issues:

- The extent to which businesses are familiar with privacy issues and requirements.

- The type of privacy policies and practices that businesses have in place.

- Businesses’ compliance with the law with respect to privacy.

- Businesses’ awareness and responses in regards to emerging privacy issues and practices.

This research addresses these objectives and will be used to guide the OPC’s approach to fulfilling its mandate with respect to Canadian businesses.

Research Design

To meet the research objectives, a telephone survey was administered to 1,006 businesses across Canada.

The following specifications applied to the survey:

- The target respondent was a senior decision maker with responsibility and knowledge of their company’s privacy and security practices.

- A detailed interviewer briefing note was prepared by Phoenix (and approved by the OPC) to brief interviewers and guide the data collection process.

- A telephone pre-test was conducted in English and French, with 10 interviews in each official language. Interviews were digitally recorded for review afterwards.

- Upon completion of the pre-test, Phoenix listened to the interviews and reviewed the resulting data. The data collected during the pre-test was not included in the final survey dataset because changes were made to the questionnaire as a result.

- Interviews averaged 15.8 minutes and were conducted in the respondent’s official language of choice.

- Calling was conducted at different times of the day and the week to maximize the opportunity to establish contact.

- Up to 10 call-backs were attempted to reach potential respondents before a sample record was retired.

- The sample was carefully monitored throughout the data collection period to ensure effective sample management to keep the study on target and maximize response rates.

- The survey was registered with MRIA’s national survey registration system.

- Sponsorship of the study was revealed (i.e. OPC).

- Data collection was conducted December 2-19, 2011.

All work performed adhered to or surpassed industry standards as determined by the Marketing Research and Intelligence Association (MRIA), the industry association for survey research, as well as applicable federal legislation (PIPEDA). In addition, all work was performed in accordance with the Standards for the Conduct of Government of Canada Public Opinion Research – Telephone Surveys.

Sample Design

A stratified random sampling approach was used for the data collection. The sampling frame was purchased from Dun & Bradstreet (D&B). A random sample frame was generated based on a sample-to-completion ratio of 10:1 for each of the three target business size quotas. The following table presents the number of sample records used to acquire the sample sizes for each business size group.

| Business Size | No. of Sample Records | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Small (1-19 employees) | N=5,998 | N=502 |

| Medium (20-99 employees) | N=2,744 | N=304 |

| Large (100+ employees) | N=1,797 | N=200 |

Additionally, the sample frame was generated in proportion to business population by region within each of the three business size groups. In total, 1,006 interviews were conducted. The interviews were distributed by region as follows:

| Region | Sample Size |

|---|---|

| Atlantic Canada | 66 |

| Quebec | 217 |

| Manitoba and Saskatchewan | 77 |

| Alberta | 140 |

| British Columbia | 155 |

| GTA | 149 |

| Rest of Ontario | 202 |

Weights were applied to the final data to adjust for the sample design. Data was weighted to the national proportion of businesses to ensure representation by size, region and industry. Canadian statistics for the number of businesses by size, region and industry were obtained through the Business Register produced by Statistics Canada.

The weighting scheme was based on three variables: business size, region and industry. The Statistics Canada “Indeterminate” category of businesses was excluded from the business size distributions used to weight the survey data.

Three sets of weights were created for each of: 1) the overall results, 2) the regional results, and 3) the results by business size. The details are as follows:

- For the overall weight, results were first weighted by business size in each region. Three size breaks (1-9 employees, 20-99 employees and 100+ employees) and seven regions (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and the Atlantic provinces) were used. They were then weighted by industry on a national level using the North American Classification System (NAICS).

- For the regional results, a second weight was developed based on region (Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia) and industry (again using the NAICS). As with the overall weight, the regional results were weighted at the national level only by industry.

- For the results by business size, a third weight was developed based on business size (1-9 employees, 20-99 employees and 100+ employees). As with the overall and regional weights, the results by business size were weighted at the national level only by industry using the NAICS.

Final Call Dispositions

The following table presents information about the final call dispositions for this survey, as well as the associated response rate (using the MRIA formula)Footnote 2 :

| Call Disposition Table | |

|---|---|

| Call Disposition | Total |

| Total Numbers Attempted | 10,539 |

| Out-of-scope - Invalid | 1,652 |

| Unresolved (U) | 2,551 |

| No answer/Answering machine | 2,551 |

| In-scope - Non-responding (IS) | 1,978 |

| Language barrier | 42 |

| Incapable of completing (ill/deceased) | 52 |

| Callback (Respondent not available) | 1,884 |

| Total Asked | 4,358 |

| Refusal | 3,111 |

| Termination | 76 |

| In-scope - Responding units (R) | 1,171 |

| Completed Interview | 1,006 |

| NQ - Quota Full - Company Size | 106 |

| NQ - Q1 (NOT FOR PROFIT/DK/REF) | 59 |

| Refusal Rate | 73.13 |

| Response Rate | 13.18 |

Notes to Readers

- Reference is made to findings from similar surveys conducted in 2007 and 2010 among Canadian businesses. Since weighting procedures and, in some cases, question wording differs among the three surveys, comparisons over time should be interpreted with caution.

- All results in the report are expressed as a percentage, unless otherwise noted.

- Throughout the report, percentages may not always add to 100 due to rounding.

- Demographic and other subgroup differences are identified in the report. The text describing these differences throughout the report is put in a box for easy identification. Only subgroup differences that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level or are part of pattern or trend are reported. For more information on subgroup analysis in this report, please see the subgroup analysis section below.

For the analysis of subgroups, characteristics have been grouped as follows:

Demographic Categories

- Core IndustriesFootnote 3:

- Accommodation and Food Services

- Administrative & Support, Waste Management and Remediation Services

- Arts, Entertainment and Recreation

- Educational Services

- Finance and Insurance*

- Health Care and Social Assistance

- Information and Cultural Industries

- Professional, Scientific and Technical Services

- Public Administration

- Real Estate and Rental and Leasing

- Retail Trade

- Transportation and Warehousing

- Utilities

- Non-Core Industries:

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting

- Construction

- Management of Companies and Enterprises

- Manufacturing

- Mining and Oil and Gas Extraction

- Other Services (except Public Administration)

- Wholesale Trade

- Other

- Region:

- Pacific (B.C., Yukon Territory)

- Prairie (includes Northwest Territories)

- Ontario (includes Nunavut)

- Quebec

- Atlantic Canada

- Business size:

- Self-employed (1 employee)

- 2-19 employees

- 20-99

- 100 or more employees

- Region:

- Quebec

- Atlantic Canada

- Alberta

- British Columbia

- Greater Toronto Area (GTA)

- Ontario (including GTA)

- The Prairies (SK,MB)

- Company Business Model:

- Sells directly to consumers

- Sells directly to other businesses/organizations

- Sells directly to both consumers and other businesses/organizations

- Revenues:

- Less than $1,000,000

- $100,000 to just under $10,000,000

- $10,000,000 to just under $20,000,000

- More than $20 million

- Company Location:

- It operates at this location only

- Other locations, but only in province

- Locations in other provinces, but only in Canada

- Other locations, including outside Canada

Attitudinal Categories

- Perceived Importance of Protecting Privacy:

- Unimportant (1-3)

- Neither (4)

- Important (5-7)

- Awareness of Privacy Obligations :

- Unaware (1-3)

- Neither (4)

- Aware (5-7)

- Perceived Difficulty of Compliance:

- Easy (1-3)

- Neither (4)

- Difficult (5-7)

- Concern Over Data Breach

- Unconcerned (1-3)

- Neither (4)

- Concerned (5-7)

Appended to the report are copies of the questionnaire in English and French.

Privacy Practices

This section outlines the practices in which businesses engage as they relate to the protection of customers’ personal information. This includes the types of customers/clients a business has, as well as the type of information they collect, how they use it, and what procedures and policies are in place to protect this information.

Variety of Company Types in Terms of Customers Served

Business representatives included in this survey work for a variety of company types in terms of the company’s target consumer. Thirty-five percent of the companies sell directly to consumers; that is, members of the general public or some subset of the public. A similar proportion (34%) sell both to the general public and to other businesses/ organizations. One quarter (25%) of the companies sell only to other businesses/organizations, while 7% provide services that do not fall into any of these categories.

Contact Information—Most Common Type of Personal Information Collected

In terms of the types of information collected about customers, the vast majority (93%) of companies collect contact information, such as names, phone numbers, and addresses. More than two thirds (68%) collect location information, such as postal codes. Other types of information mentioned by significant numbers include financial information, such as invoices credit cards, or banking records (39%), opinions, evaluations, and comments (24%), purchasing habits (17%), and medical information (10%). Five percent indicated that they collect company or personal records in general.

Information included in the 'other' category are Social Insurance Numbers, tax information, birth dates, credit checks, and identification information. In total, 5% said they do not collect any of these types of customer informationFootnote 4.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- Companies with fewer employees tended to generally collect less personal information about their customers. Self-employed Canadians were the least likely to collect location information (54% vs. 72-75% of others), financial information (18% vs. 43-53% of others), and information relating to purchasing habits (7% vs. 18-31% of others). Conversely, companies with 100 or more employees were the most likely to collect all types of information.

- Companies that sell directly to consumers were less likely than those that sell to other businesses/organizations and those that sell to both consumers and businesses to collect contact information (88% vs. 94-97%), location information (57% vs. 74-78%), and financial information (28% vs. 42-47%).

- Members of non-core industries were more likely to collect contact information (96% vs. 90% of core industries), whereas members of core industries were more likely to collect medical information (16% vs. 2% of non-core industries).

- The likelihood of collecting location information was highest amongst:

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (73% vs. 50-64% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (72% vs. 63% that are unaware).

- Those that view compliance with privacy laws as being difficult (81% vs. 66-69% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (76% vs. 63-71% that are less or unconcerned).

- The likelihood of collecting medical information was highest amongst those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (15% vs. 5-7% of others).

- Companies in British Columbia were the most likely to collect location information (80% vs. 61-74% in other regions), financial information (64% vs. 21-47% in other regions), and medical information (19% vs. 4-12% in other regions).

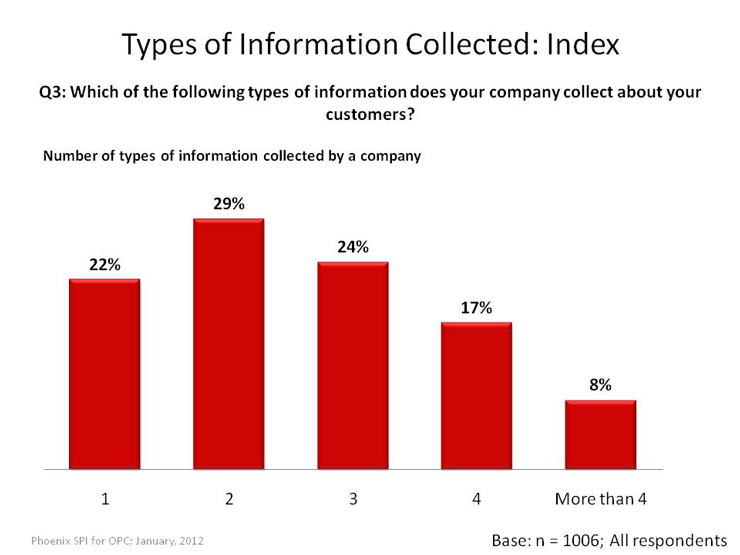

Most Companies Collect Two to Three Types of Information

In terms of diversity of information collected, most companies (53%) collect either two (29%) or three (24%) different categories of information mentioned above. A quarter collect more than that, while 22% collect less.

On-Site Paper Records—Most Common Way of Storing Personal Information

Two thirds (66%) of Canadian businesses store personal information on their customers via paper records kept on site. The next most common ways of storing customers’ personal information was desktop computers (55%), followed by on-site servers (47%). Nearly one quarter (23%) use portable devices, such as laptops, USB sticks, or tablets, while smaller proportions use cloud computing (8%) and a third party (excluding cloud computing) (7%).Footnote 5

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- Companies that sell directly to other businesses were more likely than those that sell to consumers or those that sell to both to store personal information on portable devices (32% vs. 16-22%), on-site on servers (56% vs. 35-52%) and through cloud computing (12% vs. 5-7%).

- Companies that sell both to consumers and other businesses were the most likely to store information on-site on paper (74% vs. 55-65% of others).

- Companies with fewer employees were less likely to store information on-site on servers: 23% of self-employed people do so compared with 49% of companies with 2-19 employees, 68% with 20-99 employees, and 75% with 100 or more employees. This relationship is reversed when it comes to storing information on-site on paper: 76% of self-employed persons do so compared with 65% of companies with 2-19 employees, 60% with 20-99 employees, and 56% of those with 100 or more employees.

- The likelihood of storing information through cloud computing was highest amongst:

- Companies in core industries (11% vs. 5% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than one location (14-15% vs. 6% with only one location).

- Companies that sell directly to other businesses (12% vs. 5-7% of others).

- The likelihood of storing information on-site on servers was lowest amongst those that view protecting privacy as being relatively unimportant (36% vs. 48-49% of others), those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (38% vs. 49-55% of others), and those that are relatively unconcerned over a data breach (39% vs. 50-56% of others).

- The likelihood of storing information on-site on paper was highest amongst those that view compliance with privacy laws as being difficult (79% vs. 64-65% that found it less difficult).

Most Use Multiple Methods of Storing Information

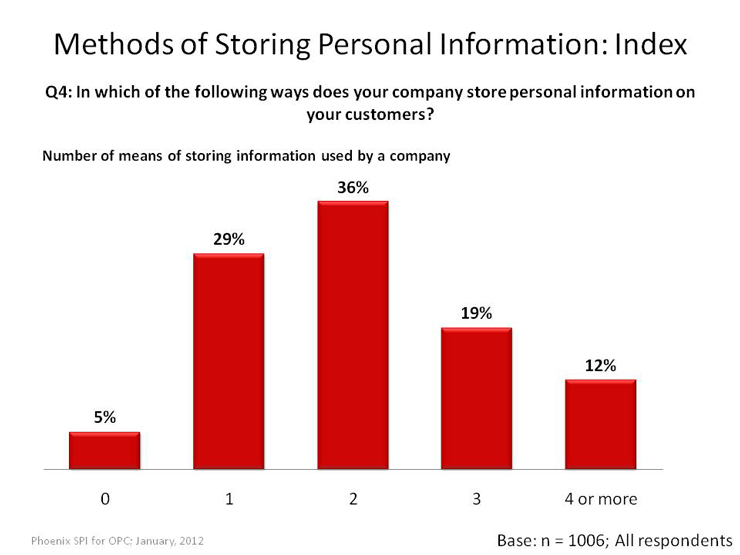

Just over two thirds (67%) of Canadian businesses use more than one method of storing the personal information they collect on their customers. The largest proportion (36%) use two methods. Conversely, 29% use only one method, while 5% do not use any.

Strong Minority Use Encryption on Portable Devices

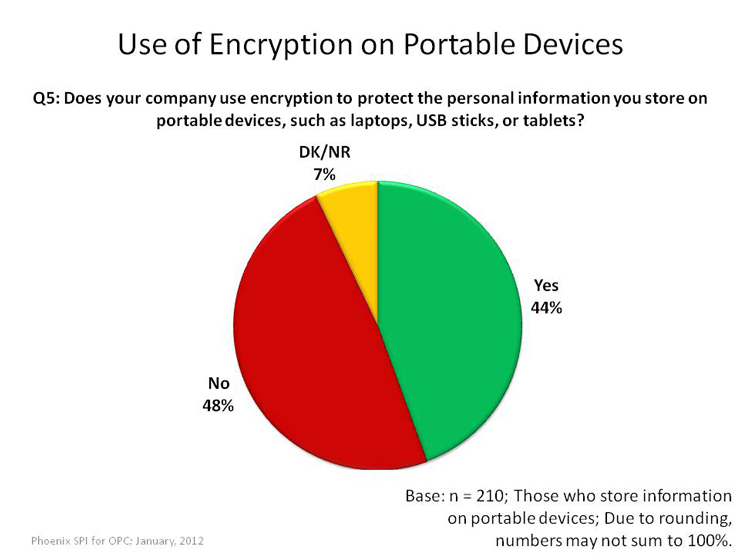

Business executives whose firms use portable devices, such as laptops, USB sticks, or tablets, to store their customers’ personal information were asked whether or not their company uses encryption to protect information stored in this way. Forty-four percent indicated that they did, whereas 48% said they did not. Seven percent were uncertain.

The likelihood of using encryption was highest amongst:

- Companies in core industries (54% vs. 33% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than 100 employees (61% vs. 27-49% of smaller companies).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (49% vs. 22-45% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (56% vs. 27-43% of others).

Most Use Variety of Methods to Protect Customer Information

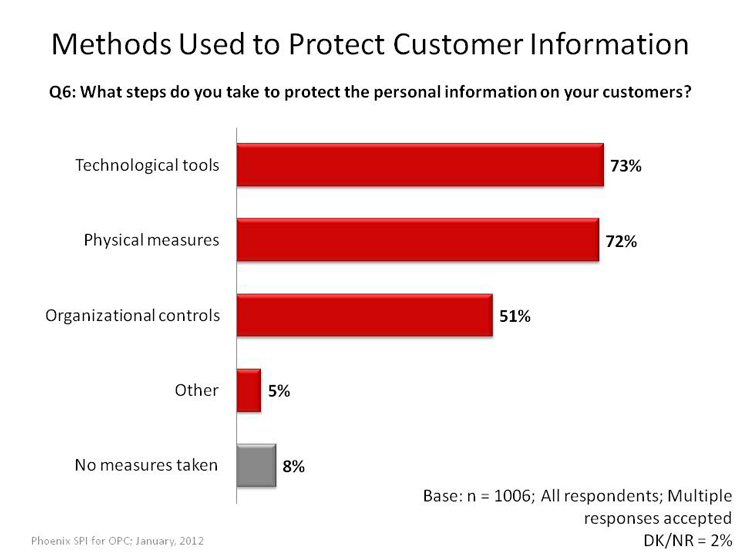

Canadian businesses use a number of methods to protect the personal information of their customers. Almost three quarters use technological tools, such as passwords, encryption, or firewalls (73%), or physical measures, such as locked filing cabinets, restricting access, or security alarms (72%). A slim majority (51%) use organizational controls, such as policies and procedures.

A small number use other methods, such as shredding/destroying information and keeping the information at home. Eight percent said they take no measures.

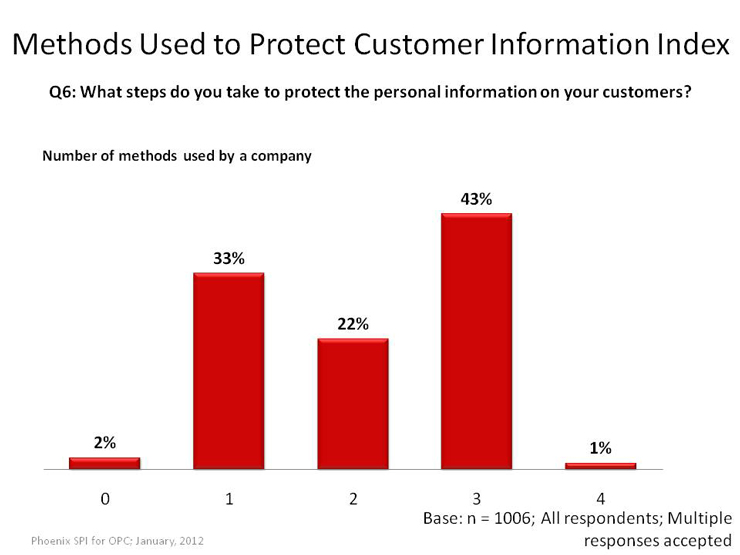

Looked at somewhat differently, 66% of Canadian businesses use more than one method to protect the personal information of their customers. Conversely, 33% use only one.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- Companies that sell directly to consumers were least likely to use technological tools (63% vs. 74-85% of others), physical measures (68% vs. 71-77% of others), and organization controls (42% vs. 55-58% of others).

- The likelihood of using technological tools, physical measures, and organizational controls all increased with the number of employees in a company. Self-employed individuals were the most likely to say they take no measures to protect personal information (16% vs. 1-6% of larger companies).

- Companies with only one location were least likely to use technological tools (70% vs. 75-86% of others), physical measures (69% vs. 73-87% of others), and organizational controls (45% vs. 57-73% of others). Conversely, the likelihood of using all three was highest amongst those with other locations but only in the same province.

- Businesses in Quebec were the least likely to use organizational controls (34% vs. 50-68% in other regions). Businesses in British Columbia, conversely, were the most likely to use them (68%).

- In terms of attitudes towards privacy issues, the likelihood of using technological tools, physical measures, and organizational controls all increased the more companies perceived privacy as important, were aware of their privacy obligations, and were concerned over a data breach. The likelihood of using physical measures was highest amongst those that perceive compliance with privacy laws to be difficult (84% vs. 72-74% of others).

Passwords—Most Common Technological Tool Used to Protect Information

Of those that reported using technological tools to protect customer information, the vast majority (96%) of such companies use passwords. As well, 79% use firewalls, while 43% use encryption.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- The likelihood of using all three technological tools was lowest amongst:

- Companies in Quebec

- Those that sell directly to consumers

- Self-employed individuals.

- Conversely, the likelihood of using all three technological tools was highest amongst companies with 100 employees or more.

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively unimportant were less likely to use passwords (90% vs. 97-100% of others) and encryption (27% vs. 39-46% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned about a data breach were most likely to use firewalls (84% vs. 73-75% of others) and encryption (48% vs. 31-40% of others).

Of businesses that use passwords, 55% have controls in place to ensure that employees use hard-to-guess passwords. Also, most require their employees to change their passwords: 16% require this monthly, 17% quarterly, 10% every six months, 12% yearly, and 7% less than this. Just over a quarter (27%) do not require their employees to change their passwords.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- The likelihood of never requiring employees to change their passwords was highest amongst companies with fewer employees: 33% of self-employed individuals say they never require a change of password compared with 29% of companies with 2-19 employees, 22% of those with 20-99 employees, and 9% of those with 100 or more employees. Larger companies also required employees to change their passwords more frequently.

- The likelihood of not requiring employees to change passwords at all was highest amongst those that perceive protecting privacy as relatively unimportant (42% vs. 25-36% of others) and companies with only one location (31% vs. 20-23% of others).

The likelihood of having controls in place to ensure that employees use hard-to-guess passwords was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (72% vs. 48-56% of smaller companies).

- Companies in core industries (62% vs. 46% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than one location (65-74% vs. 50% with only one location).

This likelihood was lowest amongst:

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as relatively unimportant (30% vs. 49-59% of others).

- Those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (44% vs. 51-61% of others).

- Those that perceive compliance with Canada’s privacy laws as neither difficult nor easy (49% vs. 64-67% of others).

Mixed Experience in Terms of Privacy Practices in Place

Business representatives were asked whether they had in place a series of mechanisms related to privacy practices. These mechanisms included:

- Having designated someone in their company to be responsible for privacy issues and personal information that the company holds

- Having staff receive training on appropriate information practices and responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws

- Having procedures in place for responding to customer requests for access to their personal information

- Having procedures in place for dealing with complaints from customers who feel that their information has been handled improperly

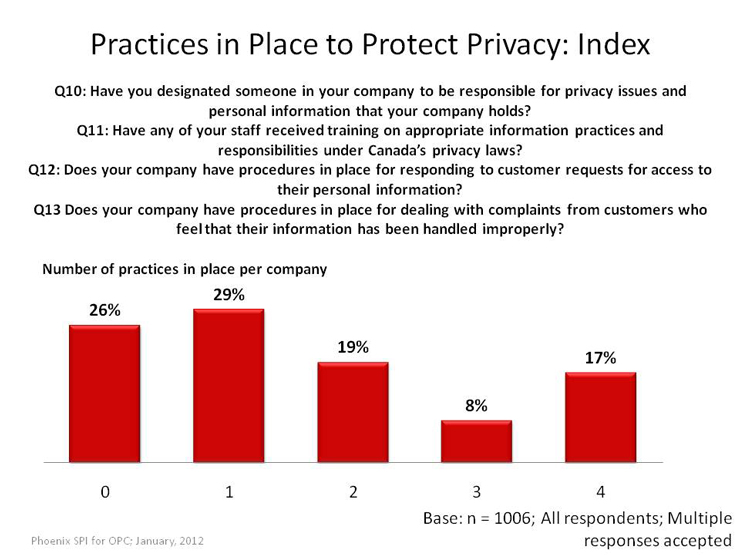

The mechanism that is most widely used, cited by three quarters, is procedures for responding to customer requests for personal information. This is followed, at a distance, by designating someone responsible for privacy (57%). Almost half (48%) have procedures for dealing with customer complaints, while only 32% ensure that their staff receive training.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

Q10:

There was a positive relationship between the likelihood of having designated someone in a company to be responsible for privacy issues and each of the following: the size of a company; the company’s perception of protecting privacy as being important; a company’s reported awareness of its privacy obligations; the company’s perceived difficulty of complying with privacy laws; and a company’s level of concern over data breaches. In accordance with these relationships, the likelihood of having designated someone in a company to be responsible for privacy issues was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (71% vs. 54-63% of smaller companies).

- Companies with locations outside of Canada (74% vs. 56-63% of others).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (62% vs. 35% that consider it relatively unimportant).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (66% vs. 46-51% of others).

- Those that view complying with privacy laws as being difficult (73% vs. 57% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned about a data breach (66% vs. 52% of others).

Regionally, the likelihood of having a designated person responsible for privacy issues in a company was lowest in Quebec (39% vs. 59-71% elsewhere).

Q11:

There was a positive relationship between the likelihood of staff receiving training and the size of a business, the importance a business attributes to the protection of privacy, a business’s awareness of its privacy obligations, the perception of complying with privacy laws as being difficult, and concern over a data breach. More specifically, the likelihood of staff having received privacy training was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (60% vs. 23-43% of smaller companies).

- Companies with more than one location (39-46% vs. 29% with only one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (36% vs. 10-29% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (43% vs. 16-23% of others).

- Those that perceive complying with privacy laws as being difficult (54% vs. 27-35% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned about a data breach (41% vs. 26-28% of others).

- Companies that sell directly to both consumers and businesses (37% vs. 25-30% of others).

- Companies in core industries (35% vs. 28% in non-core industries).

- Companies in Alberta (45% vs. 21-39% in other regions).

Q12:

The likelihood of having procedures in place for responding to customer requests for access to their personal information was highest amongst:

- Companies in core industries (84% vs. 59% in non-core industries).

- Companies in British Columbia (92% vs. 56-79% in other regions).

Q13:

The likelihood of having procedures in place for dealing with complaints from customers was highest amongst:

- Larger companies: 72% of companies with 100 or more employees have such procedures in place, compared with 60% of companies with 20-99 employees, 50% with 2-19 employees and 32% of self-employed individuals.

- Companies in core industries (56% vs. 38% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than one location (56-65% vs. 44% with only one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (54% vs. 19-51% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (61% vs. 29-42% of others).

It was lowest amongst companies in Quebec (30%) followed by those in the Prairies (38% vs. 47-61% elsewhere).

Practices to Protect Privacy Not Extensively Varied

Of the mechanisms outlined above, most companies (55%) either utilize none of them (26%) or else just one (29%). Conversely, 44% have more than one of these mechanisms in place.

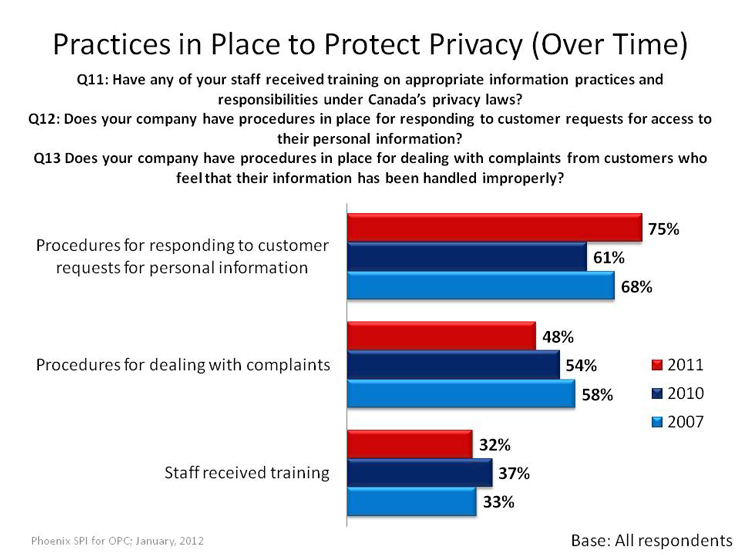

Since 2007, there has been an increase in the proportion of Canadian businesses that have procedures in place for responding to customer requests for personal information, though this increase has not been consistent. In 2007, 68% of businesses had such procedures, while in 2010 this proportion dipped to 61%, then rose again in 2011 to 75%. Conversely, 2011 saw modest declines in the proportion of businesses with procedures for dealing with customer complaints (48% vs. 54% in 2010; 58% in 2007) and having staff receive privacy-related training (32% vs. 37% in 2010 vs. 33% in 2007).Footnote 6

Privacy Policy

This section addresses business’ use of a privacy policy, including reasons for having or not having a privacy policy, frequency of updating the policy, and approaches to sharing the policy with customers.

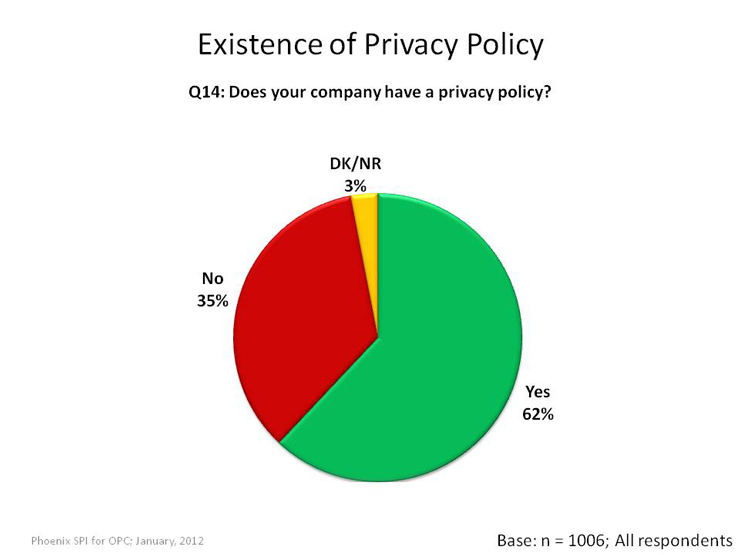

Most Canadian Businesses Have Privacy Polices

Just over three in five business executives said their company has a privacy policy. Conversely, 35% said they did not, while 3% were uncertain.

The likelihood of having a privacy policy was highest amongst:

- Larger companies: 88% of companies with 100 employees or more have a privacy policy compared with 73% of firms with 20-99 employees, 63% with 2-19 employees, and 53% of self-employed individuals.

- Companies in core industries (68% vs. 53% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than one location (72-75% vs. 58% with only one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being of greater importance (68% vs. 36-48% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of privacy obligations (71% vs. 50-53% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (69% vs. 46-59% of others).

Regionally, companies in Quebec were the least likely to have a privacy policy (47% vs. 54-70% elsewhere).

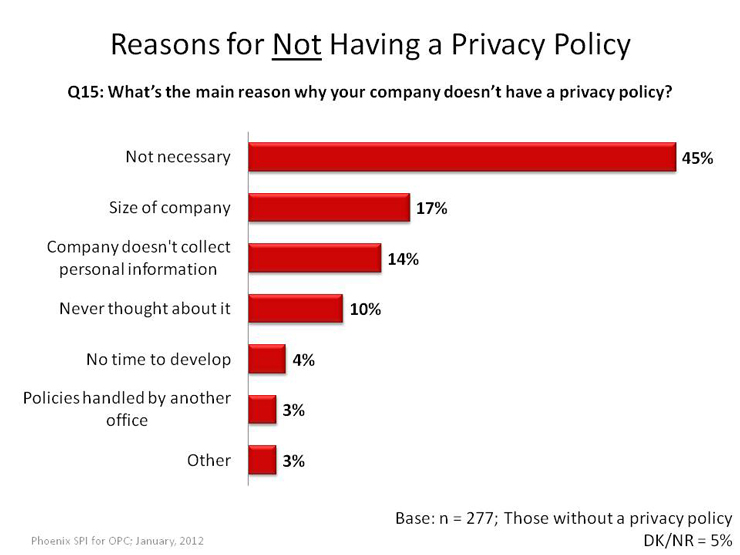

Perceived Lack of Need—Top Reason for Not Having Privacy Policy

Executives who said their company does not have a privacy policy were asked why not. The most common reason was a perceived lack of need (45%). Other reasons mentioned with some frequency include the size of the company (being too small) (17%), that the company does not collect personal information on customers (14%), and that they have never thought about it (10%).

Smaller proportions pointed to not having time to develop a privacy policy (4%), and that policies are handled by another office (3%). Included in the ‘other’ category are being in the process of developing a privacy policy and not knowing how to develop a privacy policy.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- Self-employed individuals were more likely than larger companies to think that having a privacy policy is not necessary (60% vs. 40-41%) and that the size of the company is too small (24% vs. 0-17%).

- Companies that sell to other businesses were more likely to say that the size of their company is too small to need a privacy policy (26% vs. 11-14% of others).

- Identifying never having thought about the issue was higher amongst:

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as neither important nor unimportant (41% vs. 3-8% of others).

- Those that lay midway between extremely aware and not aware at all of privacy obligations (22% vs. 7-8% of others).

- Those that were neither concerned nor unconcerned over a data breach were least likely to cite not thinking a privacy policy is necessary (25% vs. 46-48% of others).

- Those that perceived complying with privacy laws as difficult were the least likely to cite the small size of the company (6% vs. 17-18% of others).

Most Update Privacy Policy at Least Yearly

The majority of companies that have a privacy policy update their policy (57%) at least once a year: 4% do so monthly, 5% every three months, 7% every six months, and 41% every year. Sixteen percent update their policy less than once a year, while 20% have never updated their policy.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- Smaller companies were more likely than larger ones to never update their privacy policy: 28% of self-employed individuals never do so compared with 21% of companies with 2-19 employees, 9% with 20-99 employees, and 5% with 100 or more employees.

- Companies with only one location were more likely than those with multiple locations to never update their privacy policy (23% vs. 4-19%).

- The likelihood of saying they never update their privacy policy was highest amongst:

- Those that are relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (35% vs. 15-19% of others).

- Those that perceive compliance with privacy laws as neither difficult nor easy (23% vs. 10-18% of others).

- Those that are relatively unconcerned over data breaches (24% vs. 15-20% of others).

Variety of Reasons for Updating Privacy Policy

Business executives who said their firm updates their privacy policy were asked under what circumstances they do so. Roughly one quarter mentioned each of the following: scheduled reviews (26%), change in privacy legislation (25%), and changes in business practices (24%). Significant numbers also mentioned the occurrence of a problem or breach of privacy (14%), and customer complaints or concerns (13%). Six percent pointed to changes in the technology used by the company.

The likelihood of identifying changes in legislation was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (41% vs. 24-27% of others).

- Companies with locations in other provinces in Canada (51% vs. 23-24% of others).

- Those that are relatively aware of their privacy obligations (29% vs. 12-19% of others).

Companies that sell directly to both consumers and other businesses were less likely to cite a problem/breach (9% vs. 16-21% of others). They were most likely to cite changes in technologies (11% vs. 3-4% of others).

Those that perceive protecting privacy as relatively unimportant were most likely to cite complaints/concerns from customers (28% vs. 11-17% of others). They were least likely to cite scheduled reviews (3% vs. 28-32% of others).

Those that perceive protecting privacy midway between extremely important and not at all important were most likely to cite a problem/breach (39% vs. 6-13% of others) and least likely to cite changes in business practices (2% vs. 17-26% of others).

Those that consider complying with privacy laws to be neither difficult nor easy were most likely to cite complaints/concerns from customers (16% vs. 2-11% of others).

Majority Do Not Notify Customers of Changes to Privacy Policy

Most of the companies that update their privacy policy (63%) do not notify their customers about changes to the policy. Conversely, just over one third (35%) do notify customers when their company makes changes to the policy – 16% do this always, while 19% do so sometimes.

The likelihood of never notifying customers when they update their privacy policy was highest amongst:

- Companies with only one location (69% vs. 42-58% of others).

- Companies with less than 100 employees (56-71% vs. 40% with 100 employees or more).

- Those that view protecting privacy as relatively unimportant (81% vs. 61-68% of others).

- Those that are relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (76% vs. 58-67% of others).

Numerous Ways of Sharing Privacy Policy with Customers

Businesses that share their privacy policy do so in a variety of ways, with no method dominating. The largest proportion (26%) do this verbally, or over the telephone, followed relatively closely by mailing a letter (23%), using printed materials, such as pamphlets and brochures (20%), placing a notice on their company’s website (19%), and emailing customers (18%). Five percent use signs in their offices, stores or other locations. In terms of other ways of sharing their privacy policy, some said they do so in whatever way customers wish to be contacted, or that they generally keep this information current for all customers.

The likelihood of mailing a letter to customers was highest amongst those that sell directly to other businesses (41% vs. 11-19% of others) and companies with one location only (30% vs. 4-16% of others).

The likelihood of putting a notice on the company website was highest amongst companies in non-core industries (34% vs. 14% in core industries) and companies with locations in other provinces in Canada (64% vs. 12-42% of others).

Privacy as Corporate Objective

This section explores how companies perceive the importance of protecting privacy, as well as whether they consider this to be an area of corporate advantage.

Most View Protecting Privacy as Very Important

Executives were asked to rate the importance their company attributes to protecting privacy (using a 7-point scale: 1 = not important at all, 7 = extremely important). Almost half (49%) rated this as extremely important, while a further 28% rated it as at least moderately important (scores of 5-6). In total, therefore, 77% of Canadian companies attribute considerable importance to protecting privacy.

Conversely, 15% attribute relatively little importance to the protection of privacy, offering scores below the mid-point on the scale.

The likelihood of attributing higher importance (6-7) to protecting privacy was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (77% vs. 59-66% of smaller companies).

- Companies in core industries (68% vs. 53% in non-core industries).

- Those that are relatively aware of their privacy obligations (79% vs. 38-45% of others).

- Those that perceive complying with privacy laws as being relatively easy (70% vs. 57-66% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (75% vs. 52-60% of others).

- Companies in the Atlantic provinces (75% vs. 54-69% elsewhere).

Many View Protecting Privacy as Competitive Advantage

When asked how their company tends to view protecting privacy, about half of surveyed executives (52%) said they see it as neither a competitive advantage nor a corporate disadvantage. That said, 39% do view it as a competitive advantage, with 24% seeing it as a significant advantage and 15% a moderate advantage. Few (3%) view protecting privacy as a corporate disadvantage.

The likelihood of considering protecting privacy as a competitive advantage was highest amongst:

- Larger companies: 58% of companies with at least 100 employees thought this way compared with 42% of companies with 20-99 employees, 40% of companies with 2-19 employees, and 35% of self –employed individuals.

- Companies with more than one location (46-59% vs. 36% with only one location).

- Companies that attribute relative importance to protecting privacy (47% vs. 10-23% of others).

- Companies that are relatively aware of their privacy obligations (51% vs. 24-27% of others).

- Those that perceive complying with privacy laws as neither difficult nor easy (34% vs. 44-47% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a privacy breach (49% vs. 32-37% of others).

Awareness and Impact of Privacy Laws

This section explores executives’ awareness of privacy laws in Canada, as well as how their companies have reacted to the implementation of such laws. Questions in this section were prefaced with the following description of Canada’s privacy laws:

The federal government’s privacy law, the Personal Information and Protection and Electronic Documents Act or PIPEDA sets out rules that govern how businesses engaged in commercial activities should protect personal information. In Alberta, BC and Quebec, the private sector is governed by provincial laws, which are considered to be similar to the federal law.

Moderate Awareness of Company’s Responsibilities Under Canada’s Privacy Laws

Business executives were asked to rate their company’s awareness of its responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws, using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all aware, 7 = extremely aware). Almost one in five (19%) think their firm is extremely aware of its responsibilities, while an additional 35% claimed high awareness (scores of 5-6). In total, a slight majority (54%) offered positive scores above the mid-point on the scale, indicating a relatively high level of familiarity with their privacy responsibilities.

At the other end of the spectrum, 29% offered scores below the mid-point of the scale, suggesting a relatively low level of awareness.

The likelihood of reporting high (6-7) awareness of responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (55% vs. 30-40% of smaller companies).

- Companies in core industries (39% vs. 20% in non-core industries).

- Those that attribute relative importance to protecting privacy (37% vs. 9-10% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (39% vs. 17-27% of others).

It was lowest amongst those that view complying with privacy laws as neither difficult nor easy (22% vs. 40-48% of others).

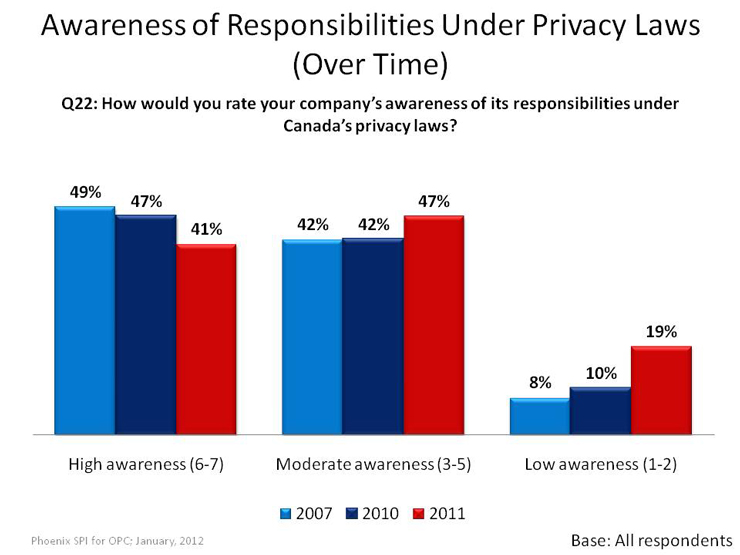

Over time, the reported level of awareness of a company’s responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws amongst businesses has declined modestly. In 2011, business executives were less likely to say that their company’s level of awareness in this regard is very high (6-7), but were more likely to say it was moderately high (3-5) or low (1-2).Footnote 7

Moderate Awareness of PIPEDA

Executives were also asked to rate their level of awareness of PIPEDA, the federal government’s privacy law, using the same 7-point scale. The results were roughly similar. Fifteen percent said they were extremely aware of the legislation, while 34% offered scores of five or six. Nearly half (49%) offered positive scores above the mid-point on the scale, once again indicating a relatively high level of familiarity with their responsibilities. However, 35% offered scores below the mid-point of the scale, suggesting a relatively low level of awareness.

Awareness of PIPEDA specifically is therefore slightly lower than awareness of responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws more generally.

The likelihood of reporting their company’s awareness of PIPEDA as very high (6-7) was highest amongst:

- Companies in core industries (36% vs. 17% in non-core industries).

- Companies with at least 100 employees (50% vs. 26-35% of smaller companies).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as relatively important (33% vs. 5-12% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (48% vs. 2-3% of others).

- Those that perceive complying with privacy laws as difficult (45% vs. 20-35% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (33% vs. 13-26% of others).

Privacy Laws Have Had a Range of Impacts for Companies

Representatives of Canadian business were asked about what kinds of impacts Canada’s privacy laws have had on their respective companies. The largest proportion (59%) said that Canada’s privacy laws rendered their company more concerned about protecting customers’ personal information. A smaller majority (52%) said that these laws have increased their company’s awareness of its privacy obligations.

Forty-seven percent reported that, as a result of Canada’s privacy laws, they have improved security associated with personal information held by their company. In addition, 36% have improved the training given to staff on privacy obligations, and 27% have had fewer breaches involving customers’ personal information.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- There was a positive relationship between company size and likelihood of experiencing the impacts of Canada’s privacy laws outlined in the preceding chart. Companies with more employees were more likely to report experiencing all of these impacts.

- The more a company reported experiencing these impacts, the more likely they were to view protecting privacy as relatively important, be relatively aware of privacy obligations, be relatively concerned over a data breach, and perceive complying with Canada’s privacy laws as difficult.

- Companies with multiple locations but all in the same province were more likely to report that their company has experienced all impacts identified in the preceding chart.

- Companies in core industries were more likely than those in non-core industries to say their company is more concerned about protecting customers’ personal information (63% vs. 55%), has improved security associated with personal information held by their company (52% vs. 40%), and has improved the training given to staff on privacy obligations (42% vs. 38%).

- Companies that sell directly to other businesses were the least likely to say their company has increased its awareness of its privacy obligations (44% vs. 54-58% of others).

- Companies in the Prairies were least likely to report having increased awareness of privacy obligations as a result of Canada’s privacy laws (33% vs. 48-62% elsewhere). This likelihood was highest in Quebec (62%).

Business executives were less likely in 2011 to say their company experienced each of the impacts outlined in the preceding chart than they were in 2010.Footnote 8 Percentage gaps between 2010 and 2011 ranged from 5-10% across the various impacts.

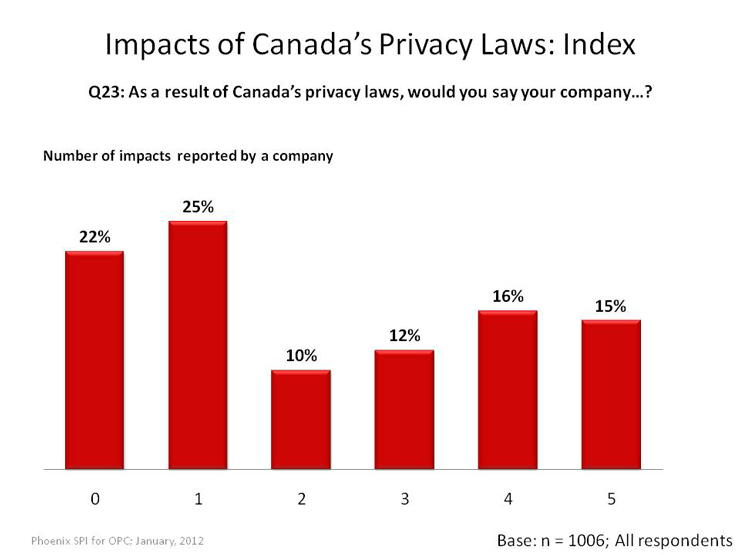

A little over half (53%) of executives reported that their company has experienced two or more of the impacts outlined in the preceding chart. Correspondingly, slightly less than half cited only one of these impacts (25%) or none at all (22%).

Compliance, Breaches and Risk Assessment

This section explores perceptions related to the difficulty of complying with Canada’s privacy laws, barriers to such compliance, issues related to data breaches, and approaches to assessing privacy risks.

Half Assess Firm’s Compliance Experience as Neither Easy nor Difficult

Business executives were asked how difficult it has been for their company to bring their personal information handling practices into compliance with Canada’s privacy laws (using a 7-point scale: 1 = extremely easy, 7 = extremely difficult). Almost half (49%) were neutral, viewing this as neither easy nor difficult. Most of the rest (34%) rated compliance with Canada’s privacy laws as easy, while only 10% felt that this was difficult for their company.

The likelihood of considering complying with Canada’s privacy laws very easy (1-2) was lowest amongst:

- Companies that sell to other businesses (21% vs. 28-32% of others).

- Companies with more than one employee (24-26% vs. 36% of self-employed individuals).

- Companies in non-core industries (23% vs. 31% in core industries).

- Those that view protecting privacy as midway between not important at all and extremely important (11% vs. 25-29% of others).

- Those that are mid-way between not concerned at all and extremely concerned over a data breach (10% vs. 27-31% of others).

The likelihood was highest amongst those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (33% vs. 20-22% of others).

Over time, the perceived difficulty of bringing personal information handling practices into compliance with Canada’s privacy laws has increased modestly, while the perception that it is very easy has decreased.

Lack of Understanding of Legislation—Top Barrier to Compliance

A lack of understanding of privacy legislation was identified most often (19%) as the top barrier or challenge in terms of complying with Canada’s privacy laws. Five percent or less cited a number of other barriers: staff/personnel requirements (5%), staff education/ awareness (4%), cost of compliance (other than staff) (3%), difficulties keeping personal information secure (3%), and challenges posed by new technology (3%). Included in the ‘other’ category, each cited by 2% or less were: keeping up to date with the law; too much paperwork/bureaucracy; barriers to accessing information; difficulties with consistently implementing policy; customer awareness; and the volume of information to protect. Sixteen percent did not think there were any challenges to compliance, while 38% offered no response.

The following subgroup differences were evident:

- The likelihood of citing a lack of understanding of the legislation was highest amongst companies that sell directly to other businesses (26% vs. 15-18% of others), companies with locations in other provinces in Canada (36% vs. 17-29% of others), and those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (33% vs. 12-21% of others). It was lowest amongst those that feel complying with Canada’s privacy laws is easy (12% vs. 22% of others).

- Companies with at least 100 employees were less likely than smaller companies to cite a lack of understanding of the legislation (9% vs. 16-20%), but somewhat more likely to cite staff education/awareness (9% vs. 1-5%).

- The likelihood of saying there were no challenges to complying with privacy legislation was highest amongst companies that sell directly to consumers (19% vs. 11-16% of others) and those that are relatively unconcerned about a data breach (19% vs. 12-15% of those more concerned).

Polarized Levels of Concern Over Data Breaches

Surveyed executives were asked to rate their level of concern about a data breach, where the personal information of their customers is compromised. They were asked to use a 7-point scale (1 = not at all concerned; 7 = extremely concerned).

One third, the largest proportion, said they were not at all concerned about a data breach, while the second largest proportion, 23% said they were extremely concerned. In total, 40% offered scores above the mid-point of the scale, suggesting significant concern about a data breach.

Before being asked this question, executives were provided with the following information:

Sometimes, sensitive personal information that is held by a company about their customers is compromised. This can be due to a range of things, such as criminal activity, a flaw in the company’s security system, or employee error, such as misplacing a laptop or other device.

High levels of concern about a data breach (scores of 6-7) were most likely amongst:

- Companies with locations in other provinces in Canada (50% vs. 22-34% of others).

- Those that attribute relatively greater importance to protecting privacy (39% vs. 10-11% of others).

- Those that report being relatively more aware of their privacy obligations (37% vs. 24% that report being relatively unaware of this).

- Those that view complying with privacy laws as being difficult (60% vs. 27-33% of others).

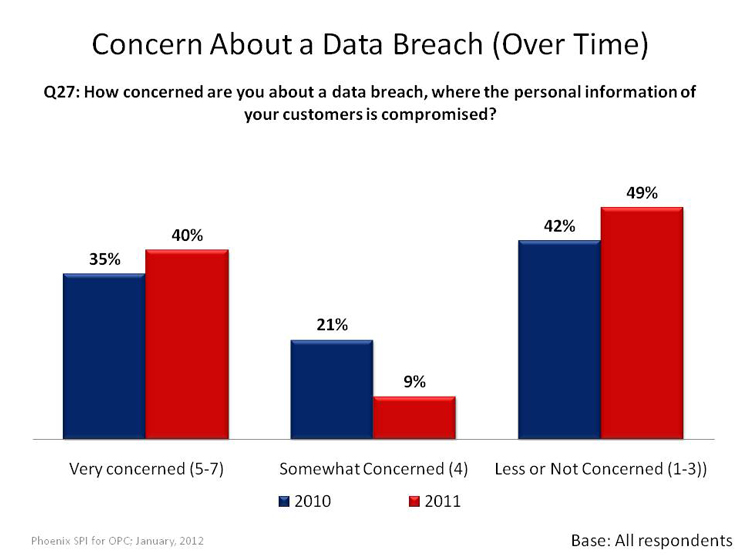

Over time, Canadian businesses have become somewhat more polarized in their level of concern over a data breach. Compared with 2010, 2011 has seen an increase in the proportion of businesses that are very concerned over such a breach (40% vs. 35%), as well as those less or not concerned at all (49% vs. 42%). Conversely, there has been a decline in those that are more moderate in their level of concern over a breach (9% vs. 21%).

Less than One Third Have Guidelines for Responding to Breach

Thirty-one percent of surveyed companies have guidelines in place in the event of a breach where the personal information of their customers is compromised. Conversely, 63% do not. Six percent of surveyed executives were unsure.

The likelihood of having guidelines in place in the event of a breach was highest amongst:

- Larger companies: 53% of companies with 100 employees or more have guidelines compared with 37% of companies with 20-99 employees, 32% with 2-19 employees, and 24% of self-employed individuals.

- Companies in core industries (38% vs. 21% in non-core industries).

- Companies with more than one location (40-49% vs. 26% with only one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively more important (37% vs. 5-19% of others).

- Those that report being relatively more aware of their privacy obligations (44% vs. 14-20% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned about a data breach (43% vs. 21-23% of others).

- Those that view complying with Canada’s privacy laws as being difficult (52% vs. 25-37% of others).

This likelihood was lowest amongst those that see complying with Canada’s privacy laws as neither difficult nor easy (25% vs. 37-52%).

Relatively Few Have Ever Experienced a Breach

The vast majority (96%) of businesses have never experienced a breach where the personal information of their customers was compromised. Conversely, only 3% have (1% were unsure).

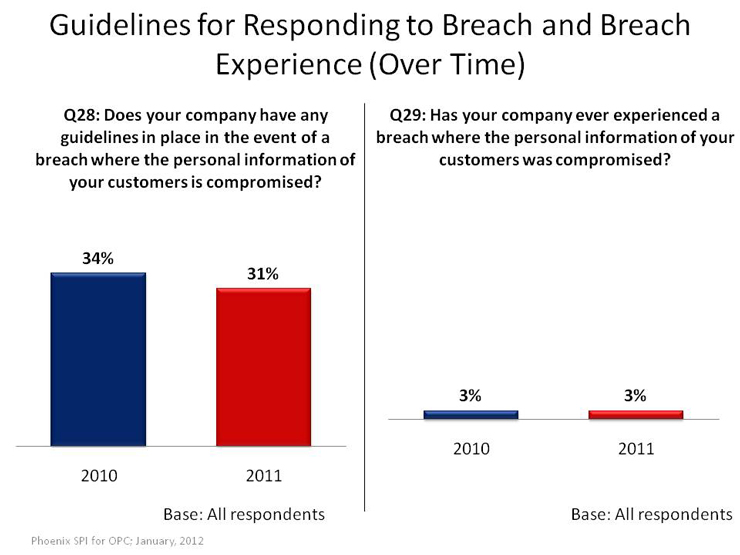

Since 2010, the proportion of companies that have guidelines in place to address a potential data breach, as well as the proportion that have ever experienced a breach, have remained relatively constant.

Business representatives whose companies have experienced a breach were asked what steps their company took to address the situation. The most common response was notifying individuals who were affected (n=16). Other responses included resolving the issue with those involved directly (n=6), notifying law enforcement (n=5), following proper procedure (n=4), reviewing the company’s privacy policy or procedures (n=4), implementing or enhancing a security system (n=4), notifying government agencies (n=4), obtaining legal counsel or taking legal action (n=3), issuing training or re-training for staff (n=2), notifying company’s internal resources (n=1), and obtaining information from government (n=1).

One Quarter Have Procedures for Assessing Privacy Risks

Approximately one quarter (26%) of Canadian businesses have policies or procedures in place to assess privacy risks related to their business. This includes assessing privacy risks associated with the development or use of new products or technologies.

Conversely, 67% of businesses do not have any such policies or procedures.

The likelihood of having policies or procedures in place to assess privacy risks was lowest amongst:

- Smaller companies: 17% of self-employed individuals had such policies and procedures compared with 27% of companies with 2-19 employees, 34% with 20-99 employees, and 56% with 100 employees or more.

- Companies in non-core industries (23% vs. 29% in core industries).

- Companies with one location only (22% vs. 28-49% with more than one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively unimportant (6% vs. 27-30% of others).

- Those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (12% vs. 23-35% of others).

- Those that are relatively unconcerned about a data breach (20% vs. 25-34% of others).

Third Parties

This section addresses companies use of third parties for processing, storage, and other services with relation to customers’ personal information.

Two thirds Aware of Accountability for Information Transferred to Third Party

Approximately two thirds (68%) claimed to be aware that when a company transfers personal information to a third party for processing, storage or other services, which can include the use of cloud computing, it remains accountable for that information. Conversely, 31% were not aware of this accountability.

The likelihood of being aware of accountability for personal information transferred to third parties was highest amongst:

- Companies that sell directly to other businesses (75% vs. 63-70% of others).

- Companies with more than 20 employees (74-82% vs. 67-69% of smaller companies).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively important (72% vs. 49-65% of others).

- Those that report being relatively aware of their privacy obligations (78% vs. 52-65% of others).

- Those that are relatively concerned over a data breach (74% vs. 63-71% of others).

Few Use Third Parties, Half That do Have Means to Ensure Information Protection

Only about one in ten (9%) Canadian businesses collect personal information from customers and send it to another company for processing, storage or other services.

Of those that do make such use of third parties, just over half (54%) reported having a contract, or some other means, in place to ensure there is appropriate protection for their company’s personal customer information.

The likelihood of using third parties was highest amongst:

- Larger companies: 17% of companies with 100 employees or more use third parties compared with 15% of companies with 20-99 employees, 9% of firms with 2-19 employees, and 8% of self-employed individuals.

- Companies in core industries (13% vs. 4% in non-core industries).

- Those that report being relatively more aware of their privacy responsibilities (13% vs. 5-6% of others).

The likelihood of having a contract in place was highest amongst:

- Companies with at least 100 employees (71% vs. 51-57% of smaller companies).

- Companies with more than one location (57-75% vs. 49% with only one location).

- Those that report being relatively more aware of their privacy obligations (66% vs. 34-37% of others).

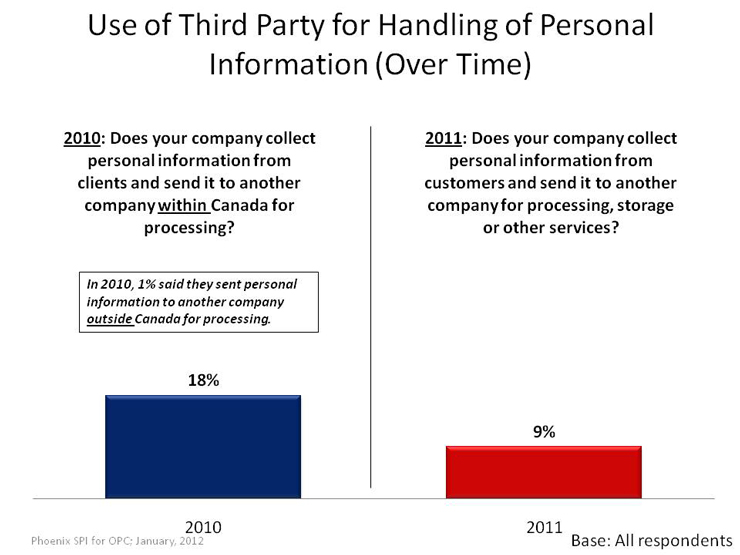

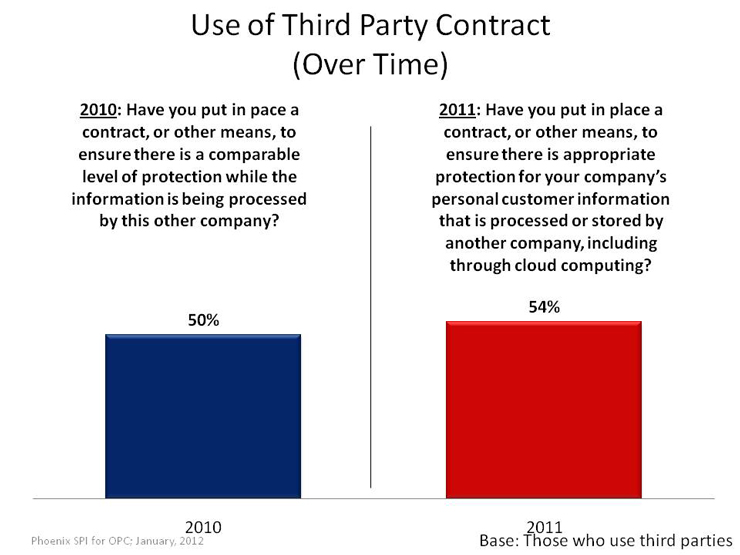

In 2011, a smaller proportion of business executives reported that their company uses third parties with regard to the handling of their customers’ personal information than did so in 2010 (9% vs. 18%).Footnote 9 A slightly larger proportion (54% vs. 50%) have a contract in place to safeguard the information they transfer to a third party.

Cooperation with Law Enforcement and Government

This section addresses issues relating to the extent of companies' cooperation with law enforcement and government in accordance with privacy laws.

One third Evaluate Customer Data to Report Suspicious or Unlawful Activity

Almost one third of businesses evaluate customer data for the purposes of identifying and reporting suspicious or unlawful activity to law enforcement or government security agencies, at least to some degree. Nine percent do this routinely, 6% do this sometimes, and 17% do this rarely. Conversely, 64% said their company never does this.

Of the companies that evaluate customer data for the purposes of identifying and reporting suspicious or unlawful activity, 28% said their company is asked to do this more often today than five years ago.

The likelihood of saying that their company never evaluates customer data for law enforcement or government was highest amongst:

- Smaller companies: 69% of self-employed individuals never do this compared with 63% of firms with 2-19 employees, 54% with 20-99 employees, and 38% with 100 employees or more.

- Companies in non-core industries (70% vs. 59% in core industries).

- Companies with only one location (68% vs. 50-59% with more than one location).

- Those that perceive protecting privacy as being relatively unimportant (78% vs. 60% that view it as relatively important).

- Those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (78% vs. 55-66% of others).

- Those that are relatively unconcerned about a data breach (72% vs. 55-59% of others).

The likelihood of saying that they were no more likely today than five years ago to be asked to report suspicious and unlawful activity was highest amongst self-employed individuals (77% vs. 55-58% of larger companies) and companies with only one location (64% vs. 23-55% with more than one location).

Communications

This section presents participant feedback on the sources and channels their companies use to gather information relating to privacy issues.

Internet—Top Potential Source of Information on Privacy Laws

The Internet (40%) is the main place that executives would go if they needed to obtain more information about their company’s responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws (an additional 5% identified Google specifically). The next largest proportion, 30%, said they would turn to the federal government. Other sources mentioned with some frequency include provincial governments (11%), the company’s internal resources (10%), and legal counsel (6%).

Included in the 'other' category are industry associations, unspecified government resources, telephone, the police/RCMP, and local/municipal government.Footnote 10

The likelihood of citing the Internet was highest amongst:

- Companies that sell directly to other businesses (46% vs. 36-40% of others).

- Companies with more than one employee (43% vs. 23% of self-employed individuals).

- Those that are relatively unconcerned about a data breach (44% vs. 29-37% of others).

The likelihood of citing the federal government was highest amongst:

- Companies in core industries (33% vs. 25% in non-core industries).

- Those that report being relatively unaware of their privacy obligations (37% vs. 20-29% of others).

- Those that consider protecting privacy to be relatively unimportant (39% vs. 17-30% of others).

The likelihood of citing a company’s internal resources and legal counsel increased with the size of the company.

Little Interest in Privacy Information in Other Languages

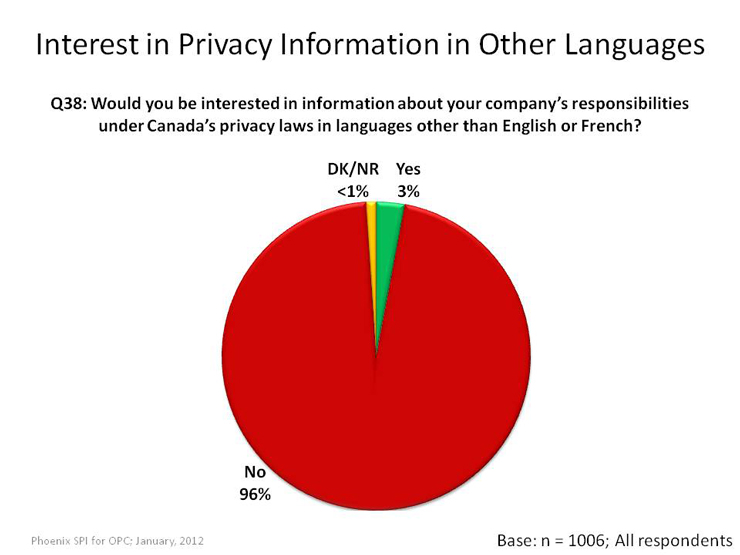

Only 3% of business executives said they would be interested in information about their company’s responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws in languages other than English or French.

The languages that were identified by those executives interested in information in other languages (n = 38), each of which was mentioned by very small numbers, include Chinese/Mandarin, Dutch, Italian, Filipino, Punjabi, Portuguese, and Spanish.Footnote 11

Internet—Top Source for Clarification of Privacy Responsibilities

Only 13% of surveyed businesses have ever sought clarification of their responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws. Conversely, 83% have not done this.