Review of passport protection practices of four federal institutions

June 30, 2021

Investigation under section 37 of the Privacy Act (the “Act”)

Description

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is accountable for the Passport Program, which issues Canadian passports in collaboration with partner institutions. Every year, our office receives reports of passports lost or stolen from federal institutions. This prompted us to examine the measures that IRCC has put in place to protect passports. We also examined the practices of 3 other partner institutions involved in the issuing of passports – Employment and Social Development Canada, Global Affairs Canada and Canada Post Corporation. We found that the 4 institutions generally had reasonable measures in place to prevent unauthorized disclosures of passports. However, we identified a few areas for potential improvement in relation to incident detection, remediation for affected individuals, and subsequent lesson-learning after passport breaches have taken place. IRCC and its partners agreed to implement our recommendations.

Takeaways

- Where an institution is responsible for an unauthorized disclosure (or potential disclosure) of a passport in contravention of Section 8 of the Privacy Act, it should take reasonable measures to reduce the risks to the individual from the contravention - including notifying the individual in a timely way, and offering concrete assistance, such as credit monitoring, where applicable.

- Appropriately and consistently assessing the risks presented to individuals from contraventions or potential contraventions of the Act is an important base step in properly remediating the risks to individuals.

- Institutions should have sound systems in place to assess security incidents involving passports for potential trends that could indicate malicious incidents. They should conduct analysis to learn from incidents that do occur, in order to protect against recurrence of contraventions of Section 8 of the Privacy Act.

Executive Summary

What we reviewed

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) manages a number of programs that facilitate the arrival of immigrants, provide protection to refugees and grant citizenship. The institution is also accountable for the Passport Program, which issues Canadian passports and travel documents, which it executes in collaboration with partner institutions.

- Section 8(1) of the Privacy Act prohibits the disclosure of personal information under the control of a government institution, without the consent of the individual to whom it relates, except under specific circumstances described in Section 8(2). None of the circumstances in section 8(2) would apply to accidental disclosures to unintended individuals (via losses or theft). In this context, we expect institutions to have in place robust protections to prevent such unauthorized disclosures. Institutions should also remediate the risks to individuals if such breaches do occur.

- Given that we receive reports of passports lost or stolen from federal institutions each year, we examined the extent to which IRCC and its partners, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Global Affairs Canada (GAC), and Canada Post Corporation (CPC) have implemented adequate controls for the protection of passports issued to prevent unauthorized disclosures in contravention of section 8 of the Privacy Act. We also examined their measures to detect and remediate such disclosures when they occur. For clarity, this report focused on passports lost or stolen before individuals receive their passport; thus, it excludes passports that have been reported lost or stolen once in possession of individuals. In this context we launched this review, under section 37 of the Privacy Act, in order to further examine and assess the severity of the issue, and if warranted, identify measures that IRCC and its partners could adopt to reduce the frequency of such contraventions of section 8 of the Privacy Act and appropriately address them when they occur.

Why this review is important

- Passports contain a range of sensitive personal information including the passport number, full name, date of birth and place of birth. In the wrong hands, a passport can represent a risk of harm to individuals from unauthorized use of a passport in their name. Stolen Canadian passports have a reportedly high black-market price, reflecting their potential value for domestic or international identity theft and/or unauthorized international travel in an individual’s name.Footnote 1

- Since Treasury Board Secretariat (“TBS”) made reporting material breaches to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (“OPC”) mandatory in 2014, our office has consistently received breach reports relating to passports lost or stolen while being processed or mailed out by the Canadian Government. Such breaches represent confirmed or potential contraventions of section 8 of the Privacy Act. Further, in 2017-2018 our office conducted a review of personal information related data breaches in the federal government. While this exercise did not focus on passport breaches, one of its observations was that there were different interpretations between institutions as to the assessment of privacy risks to individuals from lost passports. This affects what remediation steps are taken after such incidents, as is discussed in further detail below.

What we found

- Based on our examination of documents and controls relevant to the management of passports by the Passport Program, as well as interviews with officials of the four institutions, we found no indications of inadequacies in the institutions’ measures in place to prevent unauthorized disclosures of passports. Overall the volume of passports lost or stolen while under the control of the institutions is not high as a proportion of the number of passports issued.

- However, we identified a few areas for potential improvement in relation to incident detection, remediation for affected individuals, and subsequent lesson-learning after passport breaches have taken place. IRCC and its partners agreed to implement our recommendations.

Introduction

Institutions Involved

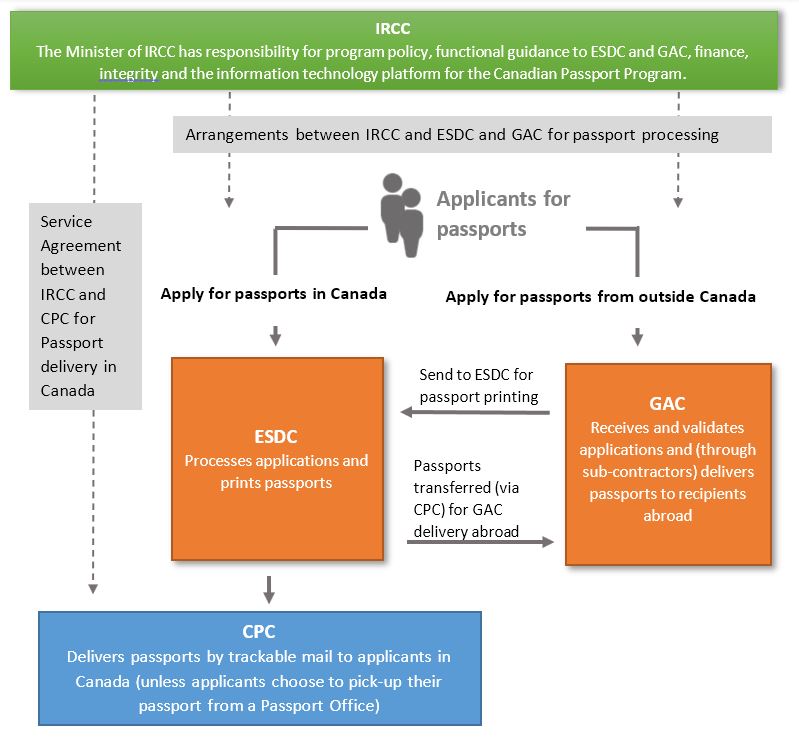

- IRCC is the lead department with regards to the Canadian Passport Program, with other institutions playing important roles. Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) is responsible for domestic service delivery, including in-person and mail intake, examination, processing, printing and call center services. Further, Global Affairs Canada (GAC) plays a role with respect to the delivery of passports abroad, through its Consular service network. In addition, the delivery of passports is primarily managed by the Canada Post Corporation (CPC) through a Memorandum of Understanding between CPC and IRCC. See figure 1 and descriptions below.

Figure 1 – Summary of roles of the institutions

Text version of Figure 1

Figure 1 – Summary of roles of the institutions

IRCC :

The Minister of IRCC has responsibility for program policy, functional guidance to ESDC and GAC, finance, integrity and the information technology platform for the Canadian Passport Program.

Arrangements between IRCC and ESDC and GAC for passport processing.

Service Agreement between IRCC and CPC for Passport delivery in Canada.

CPC

Delivers passports by trackable mail to applicants in Canada (unless applicants choose to pick-up their passport from a Passport Office)

Applicants for passports

- Apply for passports in Canada

- ESDC :

- Processes applications and prints passports

- Passports transferred (via CPC) for GAC delivery abroad

- ESDC :

- Apply for passports from outside Canada

- GAC :

- Receives and validates applications and (through sub contractors) delivers passports to recipients abroad

- Send to ESDC for passport printing

- GAC :

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada: IRCC has full functional authority for the Passport Program, which includes: responsibility and accountability for program management, the administration of the Canadian Passport Order (CPO), and the provision of full program and policy support for program delivery. The department is also responsible for processing applications for diplomatic and special passports, refugee travel documents, certificates of identity, and complex/high-risk applications for regular passports. IRCC has negotiated Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) with both ESDC and GAC for the delivery of the Passport Program.

- Employment and Social Development Canada: ESDC, through SC, is the provider of passport services in Canada for regular passports. ESDC also manages the program’s customer outreach and communication channels, including social media and the Passport Program call centres. At the time of the report, in-person passport services in Canada were mainly delivered through a network of 34 SC Passport Offices and 315 Service Canada Centres (SCC) across Canada. Service Canada also supports processing and printing of passports for applicants in the US and printing of passports from abroad.

- Global Affairs Canada: GAC is the provider of passport services internationally for regular and temporary passports, as well as emergency travel documents. At the time of the review, GAC offered 203 points of service through a network of Canadian missions abroad in support of the delivery of the Passport Program.

- Canada Post Corporation: CPC is the primary transporter of passports and passport mail in Canada and abroad (through Priority Worldwide). CPC is also responsible for tracing shipments, investigating and providing timely notification of delayed, lost, stolen or damaged shipments, providing proof of delivery or providing a letter indicating the details of incidents to the Passport Program. CPC’s mail services include pick-up and delivery of outgoing mail items and deliver addressed mail between processing centres and passport offices.

Scope and approach

- The review was conducted pursuant to section 37 of the Privacy Act (the “Act”), which empowers the Privacy Commissioner to carry out investigations in respect of personal information under the control of government institutions to ensure compliance with sections 4 to 8 of the Act.

- In carrying out our review, we examined breach reports received by our office from IRCC, ESDC and GAC over the last four years, as well as relevant records, policies, procedures and agreements of the institutions involved. This document review was supplemented with interviews with departmental officials from these three institutions and CPC, as well as the institutions’ written representations.

- In assessing the passport protection measures in place by the four institutions we also considered passport protection practices in other countries, particularly in relation to the most common cause of passport breaches reported to our Office, namely, those occurring as part of the mailing process as described in further detail below.

Criteria

- Section 8(1) of the Privacy Act prohibits the disclosure of personal information under the control of a government institution, without the consent of the individual to whom it relates, except under specific circumstances described in Section 8(2). None of the circumstances in section 8(2) would apply to accidental disclosures to unintended individuals (via losses or theft). In this context, we assessed the protections in place to prevent such unauthorized disclosures. We also examined measures in place to remediate the risks to individuals if such breaches occur.

- A number of relevant Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) policy instruments detail expectations for protective and remediation measures. These include the: Policy on Government Security, the Interim Directive on Privacy Practices, Guidelines for Privacy Breaches, Guideline on Service Agreements: An Overview, and Guideline of Service Agreements: Essential Elements.

- The assessment criteria for our review was therefore derived from section 8 of the Privacy Act and informed by pertinent TBS policy instruments related to the management and protection of personal information listed above.

Scale of Risks to Individuals

- Two key types of risks can flow from a lost or stolen passport. First, there is a risk that the passport could be used for illicit travel across borders in the individual’s name. Such use could leave a false narrative about an individual’s activities abroad that could pose a risk to them. Second, there is a risk that the passport could be used, potentially in concert with other personal information or social engineering techniques, to impersonate someone in another context – to commit identity theft or gain access to an individual’s financial or other accounts.

- Initially, before the loss or theft has been detected and reported to the authorities, both types of risk are present. Once a lost or stolen passport is reported to authorities, a process is triggered to cancel the passport and report it as lost or stolen to Interpol. Once this step has taken place, the risk of illicit travel in an individual’s name using the passport is significantly reduced, though it may remain high for illicit travel to countries which do not use Interpol records for entry and exit requirements.

- However, even after a lost or stolen passport has been detected, cancelled and flagged to Interpol, the second type of risk remains. As official government identification, a passport is still a valuable tool for a criminal attempting to impersonate someone. Private sector organizations in Canada and abroad do not have a way to know that a passport has been cancelled. So a passport represents a very useful tool for impersonating someone until after it expires – up to 10 years for most Canadian passports.

- Actual cases confirm that these risks stemming from passports lost or stolen, before or after being received by individuals, are real. CBSA advised our office that between 2017 and 2019, 19,354 individuals from across the world were intercepted for suspected fraud when trying to enter Canada travelling via airlines. This number includes 2,093 cases involving fraudulent or altered Canadian or foreign passports. Similarly, there were 1,074 cases involving an impostor using a fraudulent or a valid unaltered passport, Canadian or foreign one.

- In order to provide context regarding these risks, we compiled information for the past few years on passports lost or stolen while under the control of federal institutions.

| Year | Lost (reported to OPC as lost in transit, or misplacedFootnote 2) |

Misdirected (reported to OPC as misdirected or mis-delivered) |

Stolen (reported to OPC as stolen) |

Total (total reported to OPC) |

Total as percentage of approximate number of passports issued per year (and total reported to OPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 206 (24) | 18 (4) | 6 (1) | 230 (29) | 0.005% (0.0006%) |

| 2017 | 321 (4) | 9 (8) | 6 (0) | 336 (23) | 0.006% (0.0004%) |

| 2018 | 281Footnote 3 (23) | 35 (12) | 11 (2) | 327 (37) | 0.009% (0.0010%) |

| 2019 | 247 (36) | 2 (17) | 6 (4) | 255 (57) | 0.010% (0.0022%) |

| Total | 1,055 (87) | 64 (41) | 29 (7) | 1,148 (146) |

- We note with concern that while the overall proportion of passports lost, misdirected or stolen as percentage of passports issued remains low, it has increased year over year since 2016.Footnote 4

Observations and recommendations

Prevention of unauthorized disclosures of passports

- We reviewed a sample of privacy breach reports that we received from IRCC, ESDC and GAC. These reports mainly concerned incidents involving the domestic delivery of Canadian passports. For example, when a document was delivered to the wrong individual or when it was lost in transit. Other reports involved incidents that occurred within government of Canada premises in Canada or abroad or while being transported between them.

- We acknowledge that it would not be reasonable to expect a safeguards system for the volumes of transactions involved in passport handling by the government of Canada to prevent all unauthorized disclosures. We therefore examined the causes of these incidents, looking for patterns that could suggest particular gaps with respect to compliance with the elements described in the Criteria section above as they relate to preventing unauthorized disclosures of passports.

Inter-Agency Governance Framework

- Given the number of different involved stakeholders across multiple institutions, we examined whether the governance framework in place between the stakeholders appropriately addresses protection of passports across the institutions’ different roles.Footnote 5

- We reviewed the agreements between IRCC and its partners, and found that they clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the participants, including governance, accountabilities, service delivery, policy and program design and monitoring, performance measurement and evaluation, risk management, and financial management. This includes clauses dealing with the security and protection of information and procedures to follow in case of incidents or breaches of information. Further, the Passport Program has developed detailed process mappings in support of the governance framework.

Losses during processing of passports

- A relatively small proportion of Canadian passport breaches reported to our office occurred during the processing at IRCC, ESDC, and GAC. With respect to these incidents, we reviewed the breach reports and related policies and processes for processing of passports, supplemented by interviews with the institutions. Based on our review, we found no indications of any apparent systemic causes of those incidents that occurred prior to being mailed out.

Passports lost or stolen in transit in Canada

- Based on discussions with ESDC and the statistics presented in figure 2 above we understand the majority of the passports identified as lost or stolen, relate to passports stolen or lost (or misdirected) in the mail. In this context we examined the protections in place during transit in more detail.

- Applications for new or renewed Canadian passports made abroad represent only about four percent of the total number of such applications. We found no indications that incidents involving these passports were disproportionate, and therefore, our analysis below focuses on passports in transit within Canada.

- For passports shipped in Canada, IRCC has an agreement with CPC for the delivery of Passport Program mail to individuals. CPC uses a special tracking number type for passport mail, which contain passports, or in some cases, other Passport Program related documents.

- With respect to the prevention of theft in the mail, CPC confirmed that they currently have security controls which include alarms, safes, security cameras, access control and visitor management, and that they do regular audits of their facilities to review these controls and ensure compliance to their processes as well follow up audits on deficiencies identified. It also conducts annual Threat and Risk Assessments on selected offices based on a risk approach.

- No postal services could reasonably be expected to eliminate all losses in transit, including occasional theft of batches of mail that include passports. However, as noted above, stolen passports have value and there is consequently the potential that what appear to be losses could disguise intentional theft.

- In this context, our review compared the reported rate of lost passports (between approx. 0.005% and 0.010%) with the average rate of loss for trackable mail. We noted that the rate of loss for passports was significantly lower than the overall rate of losses for trackable mail, therefore not suggesting hidden systemic theft of passports.

Passports delivered to wrong recipients

- As noted in Figure 2 above, between 2016 and 2019 64 passports were identified by IRCC as misdirected mail. We understand this includes instances where mail was mis-addressed and where mail was correctly addressed but delivered to an unknown individual.

- With respect to mis-addressed mail, our review found that the Passport Program uses reasonable measures to ensure the accuracy of mailing addresses. Specifically, Passport Program employees print mailing labels using the address available in its Integrated Retrieval Information System (IRIS) – the main passport processing system, when labeling the envelops. If applicants fill in the passport form on line and then print it, IRIS will capture the address by scanning the barcode included in the printed form. Only where applicants complete the form manually do passport agents enter this data into IRIS by hand, with a related risk of transcription errors.

- With respect to delivery to unknown individuals, we found that in a number of incidents CPC had delivered passports via trackable mail to the address on the envelope, obtaining a signature acknowledging receipt, but the passport bearer did not receive his or her passport. CPC noted that in general, its mandate is to deliver to addresses rather than individuals.

- Canada Post does offer a proof of identity service, whereby mail can only be picked-up at a post-office with proof of identity. The use of such a service would have the ability to prevent breaches due to both mis-addressed mail (as long as the name was correct) and mail delivered to unknown individuals. However, requiring passport recipients to pick up passports in person would involve trade-offs in terms of convenience, and potentially, for certain individuals, challenges to accessibility due to geography or other factors. Therefore, in assessing whether the current practices provide reasonable assurance that assets are adequately protected, we benchmarked against practices in other countries with respect to passport delivery.

- While some foreign jurisdictions deliver passports via mail, including Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom, there are many who require in person collection of the new passport, including Germany, France, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, and Brazil. Further, in certain countries, including Mexico and Peru, all paperwork to obtain a passport is done in person at a government office after booking an appointment and the applicant leaves the government office with his newly issued passport.

- Currently, the Passport Program offers the option of in-person pick-up only at a passport office. Canada’s particular geography makes in-person pick-up of passports a greater challenge than in many countries, despite a large network of Service Canada locations. Given this, and that the overall rate of losses is not high, we are not recommending a general change to the method of delivery employed by the Passport Program. However, certain individuals may be at greater risk of an unauthorized disclosure of their passport in the delivery process, due to their living arrangements or other individual-specific risk factors. We would therefore encourage IRCC to consider offering individuals greater access to in-person passport delivery options such as pick-up at a location close to them (with proof of identity required) as an additional alternative to picking up at a passport office or delivery via trackable mail.

Detection of potential unauthorized disclosure of passports

- Timely detection of breaches, so that remediation measures can be taken quickly, is important to reducing the risk to individuals from lost or stolen passports.

- Our review of privacy breach reports showed that when incidents occurred, in the vast majority of cases, it was individuals who detected the lost or stolen passport. Most often this occurred when there was a delay in them receiving an expected passport, or in a few cases, individuals who received someone else’s passport erroneously reported it. This approach to detection appears reasonable in the circumstances, as a passport not received is unlikely to go undetected by the individual.

- However, it may take some time before an individual becomes concerned enough about a delay to report it. Our review of recent privacy breach reports submitted to our office showed that the average time length between the occurrence of the breach and the cancellation of the passport is approximately one month. In certain cases, we noted delays, for example, in a breach reported by ESDC to our office in June 2020, while the incident occurred in August 2018, Service Canada cancelled the passport in September 2019. The main reason for delays in cancelling passports is the timing of when the client contacts the Passport Program inquiring for his or her passport, which triggers a process generally leading to the cancellation of the passport.

- Our research found that, to mitigate such risks, certain countries advise the applicant when his or her passport has been dispatched. For instance, the Australian and New Zealand passport offices send an email advising the applicant that his or her passport has been mailed. Other countries such as Israel send SMS (text messages) to the applicant at various stages in the passport delivery process, including one with a tracking number to track the status of the delivery by the domestic postal service.

- We also noted countries that have measures in place to track the correct delivery of a passport. For example, in the United States applicants are encouraged to contact the passport office if they have not received their passport by mail after ten days of being mailed out. Applicants can know the status of their application by phone or using an online tool.

- Currently, GAC, IRCC and ESDC do not, as a general practice, notify individuals when their passport has been put in the mail to them - whether for a new passport or a passport being returned to them after processing. Given that the majority of the passport breaches reported to us by institutions took place in the mail, notifying individuals when their passport has been mailed to them, and instructing them on what to do if not received, would likely reduce the detection time at a relatively low cost. We would therefore encourage the institutions to consider a practice of notifying individuals when their passport has been mailed to them, and instructing them on what to do if not received within a defined time frame - in order to more quickly detect potential contraventions of Section 8 of Act to allow for timely remediation.

- In response to the above, the institutions told OPC they will review options to implement a new notification mechanism to help affected parties track passport packages and notify the Program more quickly of lost or stolen packages. IRCC, in collaboration with Passport Program partners, will review the feasibility of implementing a client notification mechanism for mail delivery into the existing complex service delivery model with support from CPC and ESDC. The target completion date is September 30, 2022.

Remediation of risk to affected individuals

- In our view, where an institution is responsible for an unauthorized disclosure (or potential disclosure) in contravention of Section 8 of the Privacy Act, it should take reasonable measures to reduce the risks to the individual from the contravention. In alignment with this, the TBS Guidelines for Privacy Breaches, and the supporting TBS Privacy Breach Management toolkit call on institutions to assess the risk from a breach to individuals, provide timely and helpful notifications to individuals where warranted to help them protect themselves, and consider other mitigation measures that may be appropriate.

- Given the risks raised following a passport breach, one key remediation activity is cancelling a passport (triggering it to be reported to Interpol as lost or stolen). Once cancelled, the first type of risk we identified above, of illicit cross-border travel in an individual’s name, is substantially reduced. In the cases we examined, we found that, once a loss or theft was detected, passports were cancelled relatively quickly.

- However, as noted above, the second type of risk, that the passport could be used to impersonate an individual in another context, such as for identity theft or accessing the individual’s financial or other accounts, persists. This is because private sector organizations in Canada and abroad do not know whether a passport has been cancelled, so a physical passport, as official government identification, remains very useful for impersonating an individual as long as the passport is not expired (up to 10 years).Footnote 6 We therefore assessed the steps taken by the institutions to remediate these longer term risks to individuals.

- Our review identified a number of concerns with the remediation undertaken, outlined in further detail below. These included (i) under-assessment of the severity of the risk to individuals from lost passports, (ii) delays in notifications to individuals, and (iii) not offering concrete assistance, such as credit monitoring, to individuals to manage the risk of identity theft.

Under-assessment of the severity of the risk to individuals from lost passports

- Appropriately assessing the risks presented to an individual from a contravention or potential contravention of the Act (such as a potential or confirmed unauthorized disclosure) is an important base step in properly remediating the risk to the individual flowing from that contravention. This is reflected in the TBS Guidelines for Privacy Breaches, under which institutions are responsible for assessing whether any particular privacy breach represents a ‘material’ breach. Material breaches are defined as ones that involve sensitive personal information and could reasonably be expected to cause serious injury or harm to the individual and/or involves a large number of affected individuals. Risk of identity theft or related fraud is specifically identified as an example of serious harm. This assessment then informs the next steps: (i) institutions must report breaches deemed ‘material’ to the OPC and TBS, and (ii) institutions are strongly encouraged to notify affected individuals, particularly if the same criteria relating to potential harm to individuals is met.

- In our view, considering the potential risks outlined above from the inappropriate disclosure of a physical passport, all lost passports (that have not been found after a search) involve sensitive personal information and could reasonably be expected to cause serious injury or harm to the individual. Therefore, in our view, they constitute material breaches.

- In this context, we were concerned to find that most incidents involving passports were not reported to our Office, and that not all institutions deemed lost or stolen passports (alone) to be material breaches. We learned that while GAC historically considered any lost or stolen Canadian passport to be a material breach, in the last few years it changed its stance and now considers such breaches material only if other documents or information were lost or stolen along with the passport at the same time. GAC contended that this is because passports lost outside of Canada present a significantly lower level of identity theft risk than for passports lost within Canada because private sector organizations overseas are more likely to require a second piece of identification. Notwithstanding this explanation of GAC, we are of the view that even if it could be confirmed that a passport alone was stolen, given its inherent sensitivity and the potential for injury or harm, we maintain it should be viewed as a material breach.

- Conversely, ESDC, which is responsible for the bulk of processing of physical passports under the Passport Program, told the OPC that historically, it did not consider a lost or stolen passport alone to be a material breach. In January 2019 they changed their policy and now does consider each breach material. Similarly, IRCC indicates that it has historically, and does currently, consider lost or stolen passports alone to be material breaches.

- ESDC and GAC did not provide us with written policies with respect to how ‘materiality’ is determined for lost or stolen passports by the respective ATIP Units. Rather, they indicated that the decisions are made by their ATIP Units based on their interpretation of the general guidance on “materiality” in the TBS Guidelines for Privacy Breaches.

- As shown in figure 2 (in paragraph 23 and reproduced below for ease of reference), over the past four years, only a quarter of passports identified as stolen were reported to OPC, and only 12% of passport related losses overall. The inconsistencies evident below, and the low overall reporting to OPC with respect to passports, raises concerns about the institutions’ assessment of the severity of the risks from passport breaches to affected individuals.

| Year | Lost (reported to OPC as lost in transit, or misplacedFootnote 7) |

Misdirected (reported to OPC as misdirected or mis-delivered) |

Stolen (reported to OPC as stolen) |

Total (total reported to OPC) |

Total as percentage of approximate number of passports issued per year (and total reported to OPC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 206 (24) | 18 (4) | 6 (1) | 230 (29) | 0.005% (0.0006%) |

| 2017 | 321 (4) | 9 (8) | 6 (0) | 336 (23) | 0.006% (0.0004%) |

| 2018 | 281Footnote 8 (23) | 35 (12) | 11 (2) | 327 (37) | 0.009% (0.0010%) |

| 2019 | 247 (36) | 2 (17) | 6 (4) | 255 (57) | 0.010% (0.0022%) |

| Total | 1,055 (87) | 64 (41) | 29 (7) | 1,148 (146) |

Delays in notifications to affected individuals and a lack of concrete assistance

- Consistent with TBS policy, institutions should notify individuals promptly when a potential contravention of section 8 of the Privacy Act occurs which presents a risk of harm to the individual - in order to help them take informed action to protect themselves as warranted.Footnote 9

- As noted above, most of the incidents of lost or stolen passports were identified by affected individuals themselves, so in most cases they were aware of a potential issue early on. Nonetheless, individuals would not, without a notification from the institution, have the benefit of additional information and assistance to help them take informed steps to protect themselves from risks such as identity theft, unless they proactively sought out this information themselves.Footnote 10

- From the sample of privacy breach reports we reviewed, the vast majority from ESDC, we noted that affected clients were notified of incidents by ESDC, on average, more than four months after the incident took place.

- Likewise, TBS and our Office were informed of incidents by ESDC, on average, more than five months after the occurrence of the incidents. In approximately half of these cases, the reports indicated that despite the passage of time, the department had not yet written to the individual notifying them of the breach and providing them with the information indicated above. Such delays are unacceptably long, rendering the notification far less effective in empowering individuals with information to protect themselves.

- Further, we found evidence that these delays occur not just in instances where the breach has been detected by the affected individual. We highlight, for example, the arrest of individuals in Saskatoon in 2019 who were stealing mail, including passports and passport applications, to commit identity fraud to open bank accounts, obtain and misuse credit cards and for purchasing products online. While the Saskatoon Police advised ESDC of these incidents in September 2019, notification to affected individuals only occurred in July 2020.

- In certain cases, ESDC noted that delays could be due to delays in discovery or to allow for investigation. However, it explained that these delays occur mainly due to the significant backlog of its Incident Management and Legislative Disclosures division, which assists the Passport Program in notifying clients affected by a breach of their personal information. While we acknowledge that resource constraints exist in many federal institutions, it is important that established procedures are followed.

- In terms of providing assistance to affected individuals to reduce their risk, we reviewed templates and sample letters of notification to affected clients used by ESDC, GAC and IRCC. We found that ESDC and GAC both include risk mitigation advice for identity theft and fraud, but that IRCC’s letters do not. Further, none of the letters included any offers to affected individuals to provide concrete assistance to manage such risk – like covering the cost of credit monitoring for a period of time. In our view, in cases where passports have been stolen or lost and not subsequently found, given the risks in question, providing concrete assistance, such as credit monitoring, is appropriate.Footnote 11

Recommendations

- OPC therefore recommended that GAC, IRCC and ESDC should jointly establish and implement: i) consistent written guidance on how to assess the “materiality” of passport related breaches which reflects the persistent risk to individuals from a lost or stolen passport; ii) reasonable service standards for timely notification to affected parties of lost or stolen passports, and, iii) include appropriate advice and consistently offer mitigation measures, such as credit monitoring, to help protect affected individuals from the longer term risks of identity theft.

Institutions’ response

- The institutions agreed to implement the three elements of the recommendation.

- With respect to i) the institutions agreed to implement the recommendation by a target completion date of November 30, 2021. The institutions’ joint response noted that IRCC will work in collaboration with Passport Program partners to develop written guidance on how departments assess the ‘materiality’ of passport related breaches and risk to individuals from a lost or stolen passport. The institutions confirmed that this will include reassessing the position on the ‘materiality’ of cases where only a passport is lost abroad, in light of this report.

- With respect to ii) the institutions agreed to implement the recommendation by a target completion date of March 31, 2022. The institutions’ joint response noted that all departments recognize the importance of notifying individuals of breaches in a timely matter and the risks associated with delays. GAC, IRCC and ESDC will continue to work together to review the current processes and reasonable service standards associated with notifying affected parties of lost or stolen passports.

- With respect to iii) the institutions agreed to implement the recommendation by a target completion date of September 30, 2022. The institutions’ joint response noted that IRCC, ESDC and GAC will review notification letters of all Passport Program partners and ensure consistent advice is provided to individuals affected by passport related privacy breaches. Passport Program partners will also review options to offer additional mitigation measures to help protect affected individuals from long term risks of identity theft.

Lessons Learned from Passport Breach Incidents

- Given both the sensitivity of passports from a privacy perspective and the meaningful incentives for theft of passports, institutions should have a sound system in place to assess security incidents involving passports for potential trends that could indicate malicious incidents, and conduct analysis to learn from incidents that do occur, in order to protect against recurrence of similar contraventions of Section 8 of the Privacy Act.

- This is aligned with the TBS Policy on Government Security which requires that institutions ensure that security incidents are assessed, investigated, documented, acted on and reported to the appropriate authority and to affected stakeholders. Further, the TBS Guidelines for Privacy Breaches states that when a security incident results in a privacy breach, institutions should conduct an investigation to identify deficiencies in security procedures or processes and should make recommendations where appropriate or when necessary to do so.

- As noted above, ESDC reports most passport-related breaches – the majority being ones which occur during transit by CPC. The ESDC notification letters we reviewed stated: “We [ESDC] take this incident very seriously and have discussed the matter with CPC in order to prevent this type of situation in the future.” However, in our interviews with ESDC, the institution was unable to corroborate the latter part of the statement. We were advised that CPC does not provide information on any specific measures to prevent future incidents. In this context, ESDC could provide no indications that they collect information to try to reduce specific risks of recurrence that may arise.

- For its part, CPC indicated that when a passport is reported as undelivered it conducts a search for the missing mail and reports to ESDC whether it was able to find the mail or not. However, it did not indicate whether it conducts investigations into their causes except in cases of confirmed thefts of CPC assets that include passports, where its Security and Investigations Services investigate and provide recommendations to prevent recurrence. It is unclear what of this information, if any, is shared with ESDC and/or IRCC.

- The IRCC Passport Program, in its leading role, tracks all passport related incidents. Detailed procedures have been established whereby CPC, ESDC and GAC inform the Passport Program when such incidents happen. IRCC contended in our review that it monitors passport incidents reported to it, and when there is a marked deviation from the normal, it reviews the incidents to determine if there is a trend/rationale and reports to senior management if necessary. However, given that ESDC, which reports the majority of the breaches, could provide no indications it collects information aimed at trying to reduce specific risks of recurrence in relation to incidents in transit, it is unclear how post-event analysis by the IRCC Passport Program is informed, and how the results are disseminated to relevant stakeholders to reduce the risks of recurrence of these unauthorized disclosures.

Recommendation

- We recommend IRCC ensure that the current incident assessment and investigation processes are robust enough to properly assess the causes of, and risk from, incidents while passports are being handled by ESDC, GAC, and CPC – to identify potential suspicious patterns and share lessons learned with all relevant stakeholders.

Institutions’ response

- The institutions agreed to implement the recommendation by a target completion date of March 31, 2022. The institutions’ joint response noted that Passport Program partners recognize the importance of safeguarding personal information of clients and ensuring measures are in place to proactively prevent privacy breaches. CPC is continuing to review their existing processes for further enhancements. In addition to the investigative process completed by CPC, IRCC agrees to review existing processes to further enhance, where possible, incident assessments and investigations.

Conclusion

- Our review found that overall, the proportion of passports issued that were disclosed in contravention of section 8 of the Privacy Act is not high, and found no indications of systemic issues in systems designed to prevent these inappropriate disclosures.

- However, given the risk that the unauthorized disclosure of passports presents to individuals, when such incidents occur, it is important that they be addressed appropriately to remediate the impact on individuals and reduce the likelihood of recurrence. In this respect, we identified a number of areas where IRCC and its partners could take measures to improve the detection, remediation and lessons learned. We are pleased that IRCC and its partners have agreed to implement our recommendations above.

- Date modified: