Veterans Affairs Canada

Section 37 of the Privacy Act

Final Report

2012

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

Follow us on Twitter: @privacyprivee

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2012

Cat. No. IP54-44/2012

ISBN 978-1-100-52495-5

Main Points

What we examined

In October 2010, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada released the results of an investigation into a complaint alleging Veterans Affairs Canada (the Department) mishandled an individual’s personal information. The Commissioner concluded that the Department was not compliant with the Privacy Act and lacked adequate controls to safeguard Veterans’ personal information.

The Department offers a wide range of programs and services to Veterans, their dependents and survivors. This requires the collection and use of sensitive personal information. We looked at how this information is managed.

We reviewed the Department’s personal information management policies, procedures and processes, program records, guidelines, privacy impact assessments, security reviews, training materials, information sharing agreements and contracts with third party service providers. We also examined the controls in place to protect the personal information stored in electronic and hard copy format. In addition, we looked at a sampling of Veterans’ files.

Finally, we examined the way in which Veterans Affairs Canada assigns privacy responsibilities, manages privacy risks and ensures compliance with its obligations under the Privacy Act.

Why this issue is important

Veterans Affairs Canada provides programs and services to over 200,000 clients. It maintains a large repository of personal information. The data holdings are not only voluminous, they are also highly sensitive. In addition to biographical data (names, dates of birth, marital status, etc.), Veterans’ files may contain military service records, employment and educational histories, and financial and medical information.

The unauthorized use and disclosure of personal information could have a significant impact on Veterans, their dependents and survivors. This could include financial loss resulting from identity theft or fraud, humiliation or damage to reputations, or risk to personal safety.

Veterans Affairs Canada has a legal obligation to ensure that policies, procedures and controls are in place to protect the personal information collected under its mandate. This is essential in order for the Department to maintain Veterans’ confidence in its ability to preserve the confidentiality of information that has been entrusted to it.

What we found

Veterans Affairs Canada takes its obligation to protect Veterans’ privacy seriously. Senior management is committed to ensuring departmental practices for the handling of personal information comply with sections 4 through 8 of the Privacy Act, and has been actively involved in monitoring the efforts made to address the deficiencies highlighted by the Privacy Commissioner in October 2010.

Key elements of a comprehensive privacy management program are in place. An internal governance structure has been formalized to foster a culture of privacy throughout the organization, and to provide a coordinated and consistent approach to managing privacy in day-to-day operations. Information management and privacy experts have been engaged to examine and identify opportunities for improving the Department’s personal information management practices. Investments have also been made in monitoring access to Veterans’ files, refining system access controls, increasing employee awareness, and developing new policies, procedures, processes and guidelines to respect Veterans’ privacy.

The principle that personal information should only be collected if there is a legitimate and authorized need is fundamental to privacy protection. Under the Privacy Act, the collection of personal information must be directly related to an operating program or activity. Veterans Affairs Canada collects personal information to administer the various benefits, programs and services under its legislative mandate. We found that the Department’s collection activities are relevant and not excessive, and that Veterans’ personal information is used for authorized purposes.

Although we found no evidence of systemic non-compliance with the disclosure provisions of the Privacy Act, there is room for improvement in terms of how Veterans’ consent is managed. As a general rule, the Department obtains consent prior to releasing a Veteran’s personal information to a third party (e.g., external service provider, family member, etc.); however, we observed consent forms that did not specify the third party or the information the Department was authorized to release. Further, we noted that disclosures had been made but the corresponding consent was not included in the file. Similarly, we found that details surrounding consent were not always entered in the Client Service Delivery Network, the primary electronic repository for Veterans’ records. A concerted effort is needed to ensure consent is consistently and sufficiently recorded on file. Otherwise, there is a risk the Department may mistakenly disclose Veterans’ personal information.

With respect to retention, the Department has schedules that set out how long personal information may be retained before it is destroyed. We found that an extremely large number of hard copy (paper) files have been kept beyond their established retention period—primarily because, in 2008, Library and Archives Canada changed the designation of the files to non-archival. This has had a significant impact on the Department; over 100,000 boxes of files must be reviewed to determine which records can be destroyed. Work is underway in this regard. We also found that the Client Service Delivery Network does not have the technical capability to dispose of records. As a result, information residing in the database is kept indefinitely.

Ensuring that access to personal information is restricted to those with a legitimate need is a key privacy safeguard. The results of the Privacy Commissioner’s investigation in 2010 prompted Veterans Affairs Canada to undertake a review of employee access rights for the Client Service Delivery Network. All positions were examined as part of the exercise. Managers were required to submit the rationale for each access level deemed essential for employees to perform their duties. The submissions were reviewed by a departmental committee and either accepted or rejected, often after questioning the rationale provided. As a result of this review, system access privileges were removed for many employees and access levels were reduced for 95 percent of the remaining positions.

Veterans Affairs Canada has identified areas for improvement in its overall information technology (IT) environment and progress has been made in addressing them; however, the Department’s IT systems have not been subjected to a formal certification and accreditation process, as required under Treasury Board policy. This exposes the Department to a risk that systems may have undetected security weaknesses, which may affect the integrity of the personal information residing in them.

The Department has contracted a third party, Medavie Blue Cross (MBC), to manage the processing of Veterans’ health care claims and certain services. As part of the arrangement, MBC implemented the Federal Health Claims Processing System (FHCPS). Although processes and procedures are in place to manage employees’ access to the FHCPS, the Department has not conducted a review to ensure access privileges are in keeping with the “need to know” principle. Our review of 26 user accounts of departmental staff found that over one-third had access to information that was not required for their defined roles. Moreover, we found that certain user activities are not recorded. While changes to a Veteran’s file are captured in system audit logs, read-only access is not. Logging user activity is crucial to determining whether access rights have been appropriately exercised. Without full activity logging, data residing in the FHCPS may be accessed with no means of detection.

With the exception of two regional offices and one district office, the Department has outsourced the disposal of Veterans’ records to private shredding companies. Approximately one-third of the arrangements are not governed by written contracts, with terms and conditions that satisfy Government of Canada security requirements. There is also an absence of systematic monitoring to verify that records are destroyed in a secure manner.

In October 2010, Veterans Affairs Canada launched a mandatory privacy awareness program for all employees. The program is supplemented by privacy-related bulletins and other resources that are accessible on the Department’s intranet site. While the various training initiatives have been successful in underscoring the importance of maintaining client confidentiality, employees would benefit from an enhanced awareness of core privacy principles.

Veterans Affairs Canada has sent a clear signal that privacy is vital to its operations. With committed leadership, structures and control mechanisms in place, the Department is moving from reacting to privacy issues to proactively addressing them.

Veterans Affairs Canada has responded to our findings. The Department’s responses follow each recommendation throughout the report.

Introduction

Background

1. In October 2010, the Privacy Commissioner released the results of an investigation into a complaint filed by an individual who alleged that Veterans Affairs Canada had mishandled his personal information.

2. The investigation confirmed that two ministerial briefing notes about the complainant contained personal information that exceeded what was necessary for the stated purpose of the briefings. Inquiries also revealed that information was inappropriately shared with departmental officials, indicating a lack of controls to protect personal information from being disseminated to those with no legitimate need to view it. The Commissioner recommended that Veterans Affairs Canada:

- develop an enhanced privacy policy framework to regulate access to personal information within the Department;

- revise information management practices and policies to ensure that personal information is shared within the Department on a need-to-know basis;

- ensure that the consent for the transfer of personal information has been obtained and that the information shared is limited to that which is necessary; and

- provide training to employees on how to handle personal information.

3. In response to the Commissioner’s report, and at the request of the former Minister of Veterans Affairs, the Department developed its Ten-point Privacy Action Plan to address the above recommendations. As part of this Plan, the Department: implemented a privacy governance structure; developed policies, procedures, processes and guidelines for managing Veterans’ personal information; established mandatory privacy training for employees; and instituted proactive monitoring of the Client Service Delivery Network, the primary electronic repository for Veterans’ personal information.

About the audit entity

4. The Veterans Affairs portfolio consists of the Department, the Veterans Review and Appeal Board, and the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman. The Department’s mandate is derived from laws—such as the Department of Veterans Affairs Act—and regulations.

5. Veterans Affairs Canada offers a wide range of programs and services to support its clients. These clients include traditional war service Veterans from the Second World War and the Korean War, and former and serving members of the Canadian Forces and eligible family members. The Department also administers disability pensions and health care benefits for certain serving and former members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

6. In 2006, the Government of Canada enacted the Canadian Forces Members and Veterans Re-establishment and Compensation Act, commonly referred to as the New Veterans Charter. The Charter introduced a new suite of programs and services for modern (post-Korean War) Veterans and their families. The Charter has two key elements. The first is an integrated case management process to address Veterans’ needs. The second is a dual award approach that separates compensation payments for the non-economic effects of a disability attributable to military service, from financial support to compensate for the impact that a service-related or career-ending disability has on a Veteran’s ability to earn income.

7. Veterans Affairs Canada has approximately 3,900 employees. It operates out of three regional offices, 35 service points across Canada and Ste. Anne’s Hospital in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue. The Department has also established 24 Integrated Personnel Support Centres with the Department of National Defence. These centres are designed to provide individuals with support throughout the transition from military service to civilian life. More information about the Department is available on its website at www.veterans.gc.ca

Focus of the audit

8. The audit focused on the management of personal information about Veterans.Footnote 1 The objective was to assess whether the Department has implemented adequate controls to protect Veterans’ personal information, and whether its policies, procedures and processes for managing such information comply with the fair information practices embodied in sections 4 through 8 of the Privacy Act.

9. The audit did not include a review of the Department’s management of personal information about its employees or contract personnel. Moreover, we did not examine the personal information handling practices of the Veterans Review and Appeal Board, the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman, the Bureau of Pension Advocates, Ste. Anne’s Hospital or the Department’s third party service providers.

10. As reported above, Veterans Affairs Canada administers disability pensions and health care benefits for certain members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The personal information management practices related to these programs and services were not reviewed.

11. Although the review included an assessment of the IT safeguards surrounding the primary client database, the audit did not examine the Department’s overarching IT security infrastructure. Information on the scope, criteria and approach can be found in the About the Audit section of this report.

Observations and Recommendations

Compliance with the Code of Fair Information Practices

12. The Privacy Act sets out the rules governing the management of personal information held by federal government institutions. Sections 4 through 8, commonly referred to as the Code of Fair Information Practices, restrict the collection of personal information and limit how that information, once collected, can be used and disclosed. The Actalso addresses the retention and disposal of personal information. It balances the legitimate collection and use requirements essential to government programs with an individual’s right to a reasonable expectation of privacy.

13. To assess the extent to which the Department is meeting its obligations under the Privacy Act, we looked at how Veterans’ personal information is managed. We expected to find that:

- the collection of Veterans’ personal information is limited to what is necessary to administer programs and services;

- the information is used and disclosed for authorized purposes; and

- ensure that the consent for the transfer of personal information has been obtained and that the information shared is limited to that which is necessary; and

- records are retained and disposed of in accordance with established schedules.

Collection practices do not extend beyond legislative mandate

14. The life cycle management of personal information begins with its collection. Within the federal context, section 4 of the Privacy Act establishes criteria for the collection of personal information. Specifically, the collection must relate directly to an operating program or activity of the government institution. The institution must also have controls in place to ensure it does not collect more personal information than necessary. We expected to find that the Department’s collection activities were both relevant and not excessive.

15. Veterans Affairs Canada collects the personal information required to administer the various benefits, programs and services under its mandate. In addition to biographical data (e.g., names, addresses, dates of birth, marital status, military service numbers), financial, medical, education, employment and military service information is often obtained.

16. Personal information may be collected directly from the Veteran or indirectly from external sources such as the Department of National Defence, community health care professionals, provincial health authorities, third party service providers and family members. Standardized applications, medical referrals, assessment templates and consent forms—authorizing the Department to collect informationFootnote 2—are routinely used for this purpose.

17. Employees who assist Veterans must exercise discretion when determining what information should be collected to address a Veteran’s needs and manage the individual’s case. The Department’s privacy policy instructs staff not to accept personal information about or from a Veteran solely because it is offered or the information may be required at a later date.

18. We reviewed the various forms used to collect personal information, interviewed staff and examined a sampling of Veterans’ files. We found the information collected on application forms and assessment templates is limited to that which is required for the purpose of assessing Veterans’ entitlements. Similarly, we found no evidence during our examination of Veterans’ hard copy and electronic files to suggest the Department is collecting personal information that it does not need to deliver its programs and services.

19. We did note however, that information relating to one financial benefit is routinely collected prior to being required. The Earnings Loss (EL) benefit is payable to a Veteran in recognition of the economic impact of a military career-ending or service-related disability on the individual’s ability to earn income. The EL benefit is intended as an income replacement provided to the Veteran during his or her participation in the Rehabilitation Program.Footnote 3 The EL benefit is also provided to a Veteran if, following the approval of a rehabilitation or vocational assistance plan, it is determined the individual is unable to work due to a permanent disability.

Financial Benefits

"Rehabilitation Program clients may also be eligible for income support through VAC's Financial Benefits Program. The Earnings Loss Benefit guarantees you will have a monthly income equivalent to 75% of your monthly military salary. It is important [emphasis added] for you to make an application for the Earnings Loss Benefit when you apply for the Rehabilitation Program."

Exhibit 1: Excerpt from the Rehabilitation Program Client Information Guide

20. We found that a completed EL benefit application and supporting documentation are collected before eligibility for the Rehabilitation Program has been determined. In essence, the information is collected with the presumption that the Veteran’s eligibility will be confirmed.

21. The Rehabilitation Program Client Information Guide provided to Veterans encourages them to submit an application for the EL benefit when they apply for the Rehabilitation Program (see Exhibit 1). The Department explained that, if the personal information required for the EL benefit was collected after eligibility for rehabilitation or vocational assistance was determined, the Veteran would face an extended delay in receiving financial assistance. While the current process may have merit from a practical perspective (i.e., reducing the turn-around-time to process the EL application), it is not in keeping with section 4 of the Privacy Act. Should the Veteran’s application be denied, the Department has, in effect, collected personal information prior to having the authority to do so.

22. It is important that Veterans be fully informed of the Department’s rationale for collecting the EL benefit application before their eligibility for the Rehabilitation Program has been established. This will enable Veterans to apply for the benefit in advance—should they choose to do so—while ensuring the Department’s collection practices satisfy the requirements of the Privacy Act.

23. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should ensure that Veterans understand they are under no obligation to submit the Earnings Loss benefit application before their eligibility for the Rehabilitation Program has been confirmed.

Department’s response:

Agreed. In an effort to make program accessibility seamless for Veterans, the Department currently includes an application for Earnings Loss with each Rehabilitation application package. To address this recommendation, the Department is now advising all applicants that they are under no obligation to apply for Earnings Loss when they apply for the Rehabilitation Program. Applicants are also advised of the benefits of applying for both programs at the same time.

Policies and practices related to the use of Veterans’ information respect privacy

24. Section 7 of the Privacy Act governs the use of personal information. Generally, a government institution may use personal information only for the purpose for which the information was obtained or compiled, or for a use consistent with that purpose. With respect to consistent uses, the Treasury Board Secretariat has provided the following guidance:

For a use to be consistent, it must have a reasonable and direct connection to the original purpose(s) for which the information was obtained or compiled.

A test of whether a proposed use is “consistent” may be whether it would be reasonable for the individual who provided the information to expect that it would be used in the proposed manner. This means that the original purpose and the proposed purpose are so closely related that the individual would expect the information would be used for the consistent purpose—even if the use is not spelled out.

25. We expected to find that the Department is using Veterans’ personal information for authorized purposes. We examined policies, procedures and processes, interviewed staff and examined a sample of Veterans’ electronic and paper files.

26. The Department requires personal information to determine eligibility and entitlements, disburse benefits, and provide services under the Department’s various programs. We found no evidence of Veterans’ personal information having been used for a purpose other than that for which it was obtained, or for a use inconsistent with that purpose.

Guidelines to limit personal information in ministerial briefing notes have had a positive impact

27. The Minister of Veterans Affairs is routinely briefed on departmental matters. The types of briefings vary and will depend on the purpose of the communication. Some briefing notes are for information purposes only, while others seek a decision on a proposed course of action.

28. The Minister also receives correspondence from Veterans and individuals acting on their behalf. These are referred to as ministerial inquiries. In addition to a draft reply, the Minister is provided with a background report containing information deemed relevant to the issue(s) raised in the correspondence.

29. In response to our 2010 investigation, Veterans Affairs Canada acknowledged that the inclusion of excessive personal information in ministerial briefing material was an issue. As part of its Ten-point Privacy Action Plan to address this and other issues, the Department established new procedures for preparing briefing notes and other documents for internal use. These procedures (guidelines) were implemented in October 2010. They are comprehensive, setting out the requirements for the inclusion, handling and sharing of personal information in briefing documents. The guidelines emphasize that briefing material should contain only personal information that is absolutely necessary [emphasis added] to meet the objective of the briefing. Employees are also instructed to consider whether this objective can be achieved without including personal identifiers, such as Veterans’ names.

30. In the fall of 2011, the Department established centralized work units to process ministerial briefing documents, and the employees involved in drafting client-specific briefing notes and background reports have received training on the new guidelines. We verified that a quality assurance process is in place to ensure the content of ministerial briefings is limited to the information the Minister needs to respond to Veterans’ concerns.

31. We reviewed a sampling of 88 client-specific ministerial briefing documents that were prepared between April 1, 2011 and March 1, 2012. We found that approximately 98 percent of them adhered to the “need to know” principle—that is, the personal information contained in the records was limited to what was necessary to fulfill the purpose of the briefing. While two briefing documents contained information that extended beyond what was strictly required, it should be noted that the briefing documents were prepared prior to the establishment of the quality assurance process.

System modified to require employees to indicate reason for accessing client database

32. Generally, an individual’s right to privacy includes control over the use of his or her personal information. In the context of this audit, this refers to a Veteran’s right to know how his or her information is used and for what purpose(s).

33. The Client Service Delivery Network (CSDN) is an integrated system that supports the delivery of disability pensions and awards, economic support, and health care benefits and services.

34. When Veterans contact the Department with questions, concerns or requests, the information is logged in the CSDN. We were informed that in 2011-12, the Department received 800,000 inquiries from Veterans and the CSDN processed over eight million interactions. An interaction may require staff in various geographical locations and different parts of the organization to access a Veteran’s file for the purpose of responding to the inquiry or facilitating the provision of a service or benefit. Moreover, a Veteran may have complex issues that require support from a number of departmental officials. Consequently, a Veteran’s CSDN file may be accessed on multiple occasions by different employees, each with a legitimate reason for doing so.

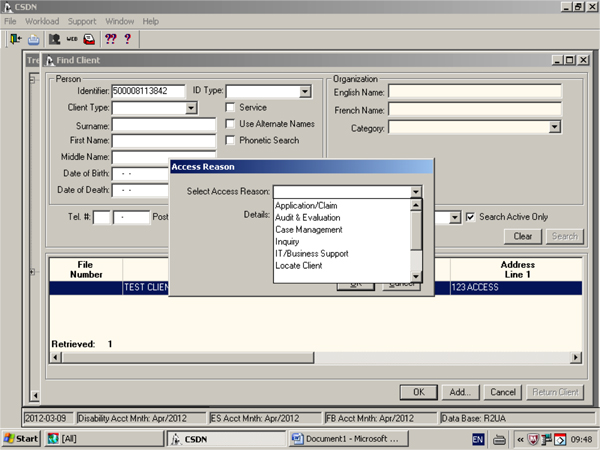

35. Although the CSDN creates a record when a Veteran’s file is opened and the information it contains is updated, staff did not consistently record the reason the account was accessed. In April 2012, a new drop-down “Access Reason” menu was introduced to capture this information and enhance the records that support the rationale for accessing a file (see below).

Exhibit 2: Client Service Delivery Network Access Reason window

36. Once the user inputs a client identifier (e.g., Veteran’s name or service number), the Access Reason window appears. The drop-down menu contains nine categories (reasons) for accessing a file. If the “Inquiry” category is selected, the user must add details about the specific nature of the inquiry. If no selection is made, or the user does not provide the additional information required, an error message appears and the user is denied access to the file.

37. This enhancement is important from a privacy perspective; it allows the Department to readily identify when a Veteran’s file has been accessed, by whom and for what reason. And, by extension, it provides valuable data in terms of monitoring system access and analyzing whether Veterans’ personal information is being used for authorized purposes.

Management of Veterans’ consent needs to be strengthened

38. As previously reported, government institutions can use personal information for the purpose for which it is collected, or for a use consistent with that purpose. They may also disclose the information for the same purposes. There are other circumstances in which personal information may be disclosed (released) without the individual’s consent. These exceptions are set out in subsection 8(2) of the Privacy Act. Such disclosures are discretionary, meaning that even if the disclosure is permissible under the Act, an institution exercises its discretion and decides whether or not to release the information.

39. We expected to find that the Department’s disclosure practices complied with the Privacy Act. We examined its policies, procedures and processes, interviewed staff and examined Veterans’ files. Although we found no evidence of systemic non-compliance, we did observe weaknesses in how consent is managed.

40. As a general practice, the Department obtains the Veteran’s consent prior to releasing his or her personal information to a third party (e.g., external health care professional, community service provider). Consent may be obtained at the time the Department collects the Veteran’s information for program use, or subsequently when the requirement for disclosure arises. The consent form contains the Veteran’s name and service number, the third party to whom the Veteran authorizes the release of the information, and the nature of the information that may be shared.

41. During our review of Veterans’ files, we found signed consent forms that did not specify the name of the third party or the nature of the information the Department was authorized to release. Moreover, we noted numerous instances of disclosure where the corresponding consent was not captured on file. It is important that consent be consistently and sufficiently recorded on file. In the absence of such sound record keeping practices, the Department cannot be assured that all disclosures are appropriate.

42. Veterans Affairs Canada receives thousands of telephone inquiries monthly. In 2004, the Department centralized its phone service, introduced a toll-free line, and established client contact centres. With operations in Kirkland Lake, Halifax, Montreal and Winnipeg, the National Contact Centre Network (NCCN) usually serves as the first point of contact for the Department. NCCN analysts receive inquiries from various sources, including Veterans and third parties acting on their behalf, community health care providers, elected officials and the public. An inquiry may be general in nature (e.g., information regarding a program or service) or it may relate to a specific Veteran.

43. Procedures are in place to guide NCCN analysts in responding to requests for personal information. If a call is received from a Veteran about his or her file, the analyst must authenticate the individual’s identity. A series of security questions are used for this purpose. When identity is confirmed, the analyst will access the Veteran’s electronic records in the CSDN and respond to the inquiry or refer it elsewhere within the Department. If the Veteran is unable to answer all of the authentication questions, the analyst is prohibited from disclosing personal information from the file.

44. The Department also receives inquiries from third parties acting on Veterans’ behalf, including family members, neighbours and representatives of the Royal Canadian Legion. We were informed that NCCN analysts will only release information if the third party holds an official power of attorney for the Veteran, or if the Veteran has identified the third party as an authorized contact—and thereby has consented to the disclosure.

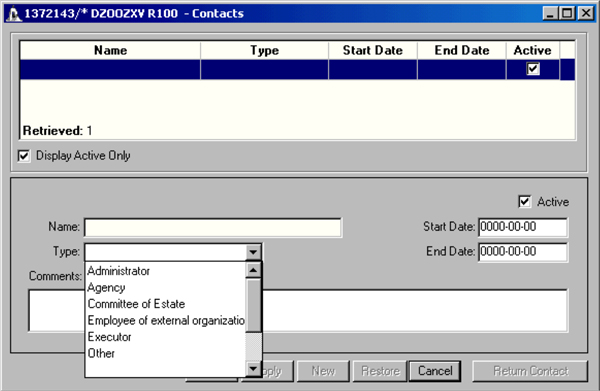

45. NCCN analysts consult the Contacts screen in the CSDN to make this determination. The screen has data fields for the authorized contact’s name, the duration of consent (start and end dates), and the information the Veteran has authorized the Department to release (recorded in the Comments field).

Exhibit 3: Client Service Delivery Network Contacts screen

46. Although not a standard practice, a Veteran’s verbal consent may be accepted to facilitate certain disclosures to third parties. For example, a family member may contact the Department regarding a specific issue. Prior to responding, the NCCN analyst will ask to speak to the Veteran, authenticate his or her identity and obtain their authorization to release the information to the family member. We were told that a verbal authorization is considered a one-time consent for a specific issue, and the circumstances of the disclosure are documented on the Veteran’s file. A written consent must be submitted if the Veteran wishes the Department to provide personal information to a family member on an ongoing basis.

47. The CSDN Contacts screen is a tool designed to mitigate the risk of an unauthorized disclosure of Veterans’ personal information. To be effective, the data it contains must be current and complete. We found a number of deficiencies in this regard: authorization end (expiry) dates were not recorded in approximately 60 percent of the electronic files examined, and the nature of the consent was absent in over one-third of the cases. While few in number, we also observed files that did not specify whether the power of attorney was for financial matters, health care or both, or whether it had been invoked.

48. Veterans have the right to withdraw or revoke their consent at any time. While the Department’s consent policy instructs staff to enter a note in the CSDN when a Veteran exercises this right, the policy is silent in terms of ensuring the Contacts screen is updated accordingly. Moreover, the employees we interviewed were generally unaware of the process for withdrawing consent, or who was responsible for ensuring such withdrawal was recorded in the Contacts screen. The current practice records a revocation of consent in a client note where it may be buried among numerous other notes; this increases the likelihood that it will be overlooked by employees unless they specifically search for it.

49. In the absence of complete and current data appearing in the CSDN Contacts screen, there is a risk that employees will disclose Veterans’ personal information inappropriately on the basis of inaccurate or outdated information.

50. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should ensure that Veterans’ consent is consistently recorded on file and easily accessible for verification.

The Department should also establish mechanisms to provide assurance that consent is accurately reflected in the Client Service Delivery Network.

Department’s response:

Agreed. Veterans Affairs Canada has recently introduced a new departmental policy on the use of privacy notices and consent. This new policy will help ensure that Veterans’ consent is consistently recorded on file.

The Department will further support its new policy through a number of changes to the Client Service Delivery Network, which will ensure consent is accurately and consistently reflected. An interim system change has been implemented on the Client Service Delivery Network, while the full system change will be complete by September 2013.

Files have been kept longer than necessary

51. Federal institutions develop retention and disposal schedules to manage their records. These schedules establish how long records will be kept before they are destroyed or transferred to the control of Library and Archives Canada. The Librarian and Archivist of Canada issues Records Disposition Authorities (RDAs) for this purpose.Footnote 4

52. We expected to find that Veterans Affairs Canada had established retention and disposal schedules for Veterans’ files, with complementary processes and procedures. Although an RDA had been issued to allow for the disposal of records that the Department no longer requires, we found that it had not been applied to a large number of eligible files.

53. Prior to 2008, all Veterans’ files in regional offices were deemed to have archival value. Consequently, the records were retained indefinitely. In 2008, Library and Archives Canada re-evaluated the Department’s information holdings and changed the designation of over 100,000 boxes of files to “non-archival” with a retention period of seven years after the death of the Veteran (or last known dependent) or, if the date of death is unknown, 100 years after the Veteran’s date of birth. This change in designation has had a significant impact on the Department as each box must be reviewed to determine which records can be destroyed. Work is underway in this regard; we were informed that 10,000 boxes of files have been processed in the last two years. The Department is exploring options to expedite the processing of the remaining files.

54. We also verified that the Client Service Delivery Network does not have the technical capability to dispose of information. Therefore, information is kept indefinitely in the database, which departmental officials acknowledge as being non-compliant with information and privacy requirements. We were told that extensive analysis is required before data can be safely deleted.

55. A records retention and disposal schedule is important from a privacy perspective. It provides a mechanism for ensuring that personal information is destroyed when it is no longer required. Any further retention exposes the information to potential misuse.

56. Recommendation

In addition to the work underway, Veterans Affairs Canada should implement processes to ensure electronic and paper records are disposed of upon the expiration of their established retention periods.

Department’s response:

Agreed. The Department has revised its retention and disposition practices for key departmental information. This involves the review of more than two million paper files. The disposal work is underway and will be fully completed by March 2015.

Due to the complexity of the Department’s primary electronic system (Client Service Delivery Network), extensive analysis will be required to assess and determine appropriate disposition of electronic data. This initial analysis and assessment will be completed by April 2013.

Safeguarding Veterans’ Personal Information

57. Sound security practices are an essential component for meeting the protection requirements established under the Privacy Act. Appropriate measures and controls must be present to ensure personal information is not subject to unauthorized access, use, disclosure, alteration or destruction.

58. Treasury Board policy establishes baseline (mandatory) security requirements to protect and preserve the confidentiality and integrity of government assets, including personal information. Federal departments and agencies are responsible for conducting their own assessments to determine whether safeguards above baseline levels are necessary.

59. We expected to find appropriate safeguards in place to protect Veterans’ personal information. We examined departmental procedures, processes, system access controls and contracts with third party service providers. We also conducted physical inspections during our visits to regional and district offices.

Risks associated with the primary client database have not been fully assessed

60. Information technology (IT) security is the process of preventing and detecting unauthorized use of computer systems. Evolving technology presents threats that may affect the confidentiality and integrity of personal information. To prevent unauthorized access to any part of a computer system, institutions must protect data through the use of appropriate safeguards. IT systems should also be subject to ongoing monitoring, as well as routine vulnerability assessments and testing.

61. Although the audit was not designed to examine the Department’s overarching IT security infrastructure, we did look at the measures in place to protect its operational systems. We found that the Department has implemented administrative, physical and technical safeguards that adhere to standard industry practices. These include firewalls, intrusion detection systems, network zoning and effective change management. The IT systems are housed in secure areas with restricted access.

62. Veterans Affairs Canada has identified areas for improvement in its overall IT environment and progress has been made to address them. A more rigorous threat and risk assessment (TRA) process has been implemented and vulnerability assessments have been performed on public-facing applications. While threat and risk assessments are prepared for new systems, they have not been conducted on all existing systems. The Department was in the process of conducting a TRA on the Client Service Delivery Network (CSDN) at the time we completed our audit.

63. Treasury Board Secretariat’s Operational Security Standard: Management of Information Technology Security requires federal organizations to certify and accredit an IT system prior to approving it for operation. Certification verifies that mandatory security requirements for an IT system have been applied. It also verifies that controls and safeguards to protect data are functioning as intended. Accreditation signifies that management has authorized operation of the system and has accepted any residual risk.

64. The Department’s IT systems, including the CSDN, have not been subjected to a formal certification and accreditation process, as required by Treasury Board’s security standard. This exposes the Department to a risk that systems may have undetected security weaknesses that could affect the integrity of the personal information residing in them.

65. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should establish a formal certification and accreditation process and ensure that all IT systems that retain personal information are subjected to it.

Department’s response:

Agreed. In consultation with the Chief Information Officer Branch of the Treasury Board Secretariat, Veterans Affairs Canada will establish a process for Certification and Accreditation of all its IT systems that retain personal information. This process will be in place by December 2012. The Department’s largest and most critical electronic system, the Client Service Delivery Network, will be the first system subjected to this process.

Employee access rights to electronic data have been modified to respect the “need to know” principle

66. Controlled access to an IT system represents a key safeguard because it restricts the use of personal information to those who have a legitimate need. An effective method of mitigating the risk of data being compromised is to limit access rights to the system. We looked at:

- how the Department determines who needs access to the CSDN and to what information within the system; and

- the administrative processes and procedures in place for ongoing management of this access.

67. Approximately 70 percent of the Department’s employees provide direct service to Veterans. Access to information within the CSDN is based on an employee’s position and the requirements of that position. Many employees may have the same position; for example, the Department employs 246 case managers.Footnote 5 The CSDN has several access levels; each level establishes the type (subset) of information that an employee can view and the functions the employee can perform within the system.

68. In November 2010, the Department established a committee to review access to the CSDN. All positions were examined as part of this exercise. Questionnaires to validate access requirements were developed and sent to all units. Managers and supervisors were required to submit the rationale for the CSDN access levels deemed essential for employees to fulfill their job functions. The submissions were reviewed and either accepted or rejected, often after questioning the rationale provided. Once CSDN access levels for a position were approved, the access levels of all employees occupying that position were revised accordingly. This process was completed in February 2012.

69. We confirmed that CSDN access has been removed for 45 positions (499 employees). Moreover, access levels were reduced for 95 percent of the remaining positions. This is a positive development from a privacy protection perspective; the Department has exercised due diligence in reassessing who should have access to the system, as well as the level of such access.

70. We also found that the Department has processes and procedures to grant, remove and manage access to the system. To obtain access, a request is submitted to a central unit. This unit verifies that the employee requires access and then grants the level assigned to the employee’s position. Should the employee change positions, the access level is modified to reflect the requirements of the new position. If an individual leaves the Department or is absent on extended leave, access rights are removed.

71. We did note that the Department uses a manual process to establish and maintain access levels. Access rights are assigned to each individual rather than assigning the employee to a pre-defined role within the system that contains the necessary access levels. Since manual procedures are more prone to error, there is a risk that users may be granted inappropriate levels of access.

72. Automated role-based access within a system facilitates the ongoing management of access rights. It grants access permissions to roles and assigns employees to those roles. Changes made to the access levels of a role are automatically assigned to all employees with that role. In other words, access levels can be verified by confirming employees have the correct role rather than examining the validity of each specific access level assigned to an employee.

73. Recommendation

To mitigate the risk of employees having access to Veterans’ information that they do not need, the Department should automate role-based access for the Client Service Delivery Network.

Department’s response:

Agreed. As part of the Department’s original Ten-point Privacy Action Plan, issued in November 2010, a significant review of access rights to the Client Service Delivery Network was completed in February 2012. As a result of this review, the Department will automate role-based access for the Client Service Delivery Network by April 2013.

Enhanced activity logging is required to monitor access to client health care claims

74. Veterans Affairs Canada provides a wide range of health care benefits and services to clients, including medical, surgical and dental treatment; aids for daily living; special equipment; and prescription drugs. The Department has contracted a third party, Medavie Blue Cross (MBC), to manage the processing of Veterans’ health care claims. As part of this arrangement, MBC developed the Federal Health Claims Processing System (FHCPS), which it owns and operates. The FHCPS provides automated claims adjudication, issues payments to medical service providers and processes reimbursements to Veterans for eligible expenses. MBC issues client health identification cards to facilitate the provision of many services and benefits.

Exhibit 4: Medavie Blue Cross client health identification card

75. We expected to find adequate safeguards in place to protect personal information transmitted to, and stored within, the FHCPS. We also expected to find that access to the data is restricted to those with a legitimate need. We examined policies and procedures, IT security controls and the processes for managing access to the system.

76. The Department commenced outsourcing the management of client health care claims in 1989. The current agreement with MBC was established in 2003. It contains key security and privacy provisions, including:

- all work and services must be performed in Canada by Canadian citizens;

- security and physical measures to protect Veterans’ information must be in accordance with Government of Canada security standards;

- the information collected must be directly required for the purpose of providing the services stipulated under the contract;

- the information cannot be used for secondary purposes;

- MBC must obtain client consent forms to support program administration; and

- employees with access to Veterans’ information must have Enhanced Reliability security clearance.

77. Although not required under the contract, the Department and MBC have established a protocol for reporting a privacy breach. In addition to identifying the individual(s) impacted by a breach, MBC provides the Department with a summary of the incident, the results of its investigation, and any corrective action taken to prevent a recurrence.

78. As reported above, the FHCPS is owned and operated by MBC. While the company’s overall IT security infrastructure was not examined as part of the audit, we did confirm that a secure, dedicated link is used to transfer data electronically between Veterans Affairs Canada and MBC. The Department works with MBC to ensure appropriate IT security controls are in place. These controls are tested regularly and reviewed annually by an external auditor. The external review assesses the effectiveness of the controls surrounding system access management, as well as physical, network and application controls. A copy of the external audit report—and MBC’s management action plan to address any reported deficiencies—is provided to the Department.

79. Veterans Affairs Canada and MBC share responsibility for managing access to the FHCPS, with each entity retaining control over granting, modifying and removing access rights for their respective employees. MBC has established procedures for this purpose; they include confirming employees are Canadian citizens, have been security cleared, and require access to the system to perform their duties. Processes are also in place to remove or modify FHCPS access if an employee transfers to a new position, departs or is absent on extended leave. The controls established by MBC to manage system access rights are examined annually as part of the external audit.

80. In terms of the Department, the processes and procedures for managing access to the FHCPS mirror those used for the CSDN. This includes the use of a manual process to establish and maintain access levels, as well as assigning FHCPS access rights to individuals rather than assigning them a role within the system.

81. However, unlike the CSDN, Veterans Affairs Canada has not completed a review of FHCPS user privileges to ensure access is in keeping with the “need to know” principle. Our testing indicates there are weaknesses in this regard. We reviewed a sampling of 26 users (departmental employees) and found that over one-third had access to information that was not required for their defined roles.

82. Moreover, we found that certain user activities are not recorded. Although changes to a Veteran’s file are captured in FHCPS audit logs, read-only access is not. Logging user activity is crucial to determining whether access rights have been appropriately exercised. Without full activity logging, a Veteran’s file may be accessed with no means of detection.

83. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should review employees’ access to the Federal Health Claims Processing System to ensure user privileges are in keeping with the “need to know” principle. The Department would benefit from automating role-based access within the system.

Veterans Affairs Canada should also ensure that all user activities, including read-only access to files, are logged for monitoring and audit purposes.

Department’s response:

Agreed. Veterans Affairs Canada has engaged the current Federal Health Claims Processing System contractor to ensure user privileges are in keeping with the “need to know” principle. Additionally, the Statement of Requirements for the new contract addresses both issues raised in the recommendation. A Request for Proposal (RFP) will be posted to MERX in 2012. The present contract expires in 2015.

There is no record of actions taken to address security risks identified during site inspections

84. Treasury Board Secretariat’s Operational Security Standard on Physical Security provides mandatory requirements to counter threats and risks to government assets, including personal information. We expected to find that physical safeguards to protect Veterans’ personal information were commensurate with the sensitivity of the information.

85. The Department’s head office, regional and district offices are controlled by various security measures. Intrusion detection alarm systems, electronic access control cards and secure storage facilities are commonly used to restrict access to operational areas and records. These safeguards are complemented by the presence of security guards and closed-circuit television cameras at some locations.

86. The Security and Real Property Division conducts site inspections at each regional and district office on a three-year rotational basis. The inspections identify security risks and recommend strategies to minimize them, and thereby improve the Department’s physical security environment. The assessments address various issues, including perimeter security, physical access controls, and the security of sensitive assets and information.

87. We reviewed a sampling of 20 site inspection filesFootnote 6 and found they were silent on whether the security risks highlighted in the reports had been addressed with the implementation of appropriate mitigation measures. The files also lacked confirmation of senior management’s review and acceptance of the findings and recommendations. Departmental security officials confirmed that regional and district managers are not required to formally respond to the findings or provide records highlighting the actions taken to address noted deficiencies. In the absence of formal sign-off by senior management, there is no assurance that security risks that may impact Veterans’ privacy have been fully considered.

88. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should ensure all actions taken to address observations noted during physical security site inspections are appended to the assessment reports. In addition, management should, through sign-off, formally acknowledge and accept the risks identified in these assessments, as well as the mitigation measures—either taken or planned.

Department’s response:

Agreed. Veterans Affairs Canada has already revised its site review process to require that management action plans be appended to the assessment reports and address any identified risks, including a follow-up mechanism.

Particularly sensitive personal information is sent by fax

89. The use of facsimile (fax) technology to transmit personal information poses certain risks. If sent by unsecure means, the information may be intercepted or exploited. It could also be inadvertently sent to the wrong individual, or a fax machine may be accessible to many employees in an office environment, thereby increasing the risk that the contents of the message may be exposed. Consequently, faxing should be used judiciously and measures should be adopted to mitigate the risk of an inappropriate disclosure.

This facsimile service is a non-secure facility. Information that is classified as top secret, confidential or medically-related client/personal information shall not be transmitted on the facsimile network.

Protected information, including particularly sensitive information (except for medically-related client/personal information), may be sent over the facsimile network if authorized by the responsible manager.

Exhibit 5: Notice on facsimile cover sheet

90. Departmental policy provides direction to staff on the use of fax technology to transmit client information. While the policy outlines additional precautions—such as contacting the recipient prior to sending a message, verifying the fax number and confirming receipt of the transmission—it places limited restrictions on the type of Veterans’ information that may be faxed. The only guidance in this regard is found on the Department’s standard fax cover sheet, which contains a notice stating that, “medically-related client/personal information must not be sent over the facsimile network.”

91. We found that Veterans’ information is often faxed, both within the Department and to external recipients. Although referrals to medical service providers and consent forms account for many of the transmissions, our interviews with staff and examination of files confirmed that faxes may include information about a Veteran’s general health or psychiatric conditions, as well as pension-related information. The practice of transmitting such information by fax contravenes the instructions provided on the fax cover sheet.

92. The standard fax cover sheet is also deficient. It does not include a warning that the information is intended for the named recipient only, or that any unauthorized use, disclosure or distribution is prohibited. Moreover, it does not provide explicit instructions for the recipient to follow if a fax is received in error.

93. The Treasury Board Secretariat’s Guidelines for Privacy Breaches outline a number of measures to prevent the unauthorized disclosure of personal information. They advise against sending personal information by fax unless absolutely necessary. Our inquiries suggest that faxes are often used by Veterans Affairs Canada for reasons of expediency (convenience), rendering privacy a secondary consideration.

94. Recommendation

To mitigate the risk of inappropriate disclosure, Veterans Affairs Canada should ensure that the use of fax technology to transmit sensitive personal information is restricted to such cases where it is required by time constraints.

The Department should also ensure that its standard fax cover sheet includes a statement regarding the confidentiality of the message, and provides instructions for notifying the Department in the event that a fax is received in error.

Department’s response:

Agreed. The Department has revised its standard fax cover sheet with a statement regarding the confidentiality of the message, as well as instructions for notifying the Department in the event a fax is received in error. In addition, communication has been issued to staff regarding the appropriate use of fax.

Inspection of telework sites would ensure privacy risks are addressed

95. The Treasury Board Secretariat issued its Telework Policy in 1999, the objective of which is “to allow employees to work at alternative locations, thereby achieving a better balance between their work and personal lives, while continuing to contribute to the attainment of organizational goals.” Employee participation in a telework arrangement is voluntary and at the discretion of the employer; no employee is entitled to telework.

96. Veterans Affairs Canada has approved telework as an option for staff seeking flexible work arrangements. We expected to find adequate controls in place to mitigate the risks associated with employees managing Veterans’ personal information off-site.

97. The Department’s Telework Policy incorporates key elements of the Treasury Board policy. It is complemented by a telework agreement, which must be signed by the employee, the supervisor and a delegated manager. The agreement sets out the administrative terms and conditions of the arrangement, and establishes the employee’s responsibility to protect client information and comply with departmental security policies, standards and procedures.

98. Teleworkers are issued encrypted laptop computers and secure filing cabinets. Remote access to the Department’s IT systems is provided through a secure, encrypted connection. Although these measures establish a sound framework for protecting Veterans’ personal information, inspections of telework sites would provide an enhanced level of assurance. At the time of the audit, 14 district offices had teleworkers. We were informed that six of the offices inspect telework sites; the remaining eight offices do not.

99. Telework extends the workplace beyond the relatively secure physical environment of an office building, which is generally protected by an intrusion detection system, electronic access cards and other security measures. These are typically absent at telework sites; this reduction in security renders the sites vulnerable to risks that could impact privacy. Therefore, it is essential that the Department verify that appropriate safeguards are in place to protect Veterans’ personal information. A site inspection is an effective tool for identifying and addressing security and privacy risks that can be detected only by observing the telework environment.

100. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should, with notice and consent, inspect alternative work locations to ensure that adequate security and privacy safeguards are in place to protect personal information.

Department’s response:

Agreed. The Department has inspected all telework locations to ensure adequate security and privacy safeguards are in place.

Informal arrangements provide little assurance that records are disposed of securely

101. Section 6(3) of the Privacy Act requires government institutions to dispose of personal information in accordance with the Regulations and any directives or guidelines issued by the Treasury Board Secretariat. The Treasury Board’s Operational Security Standard on Physical Security provides minimum requirements to ensure protected and classified records are destroyed securely.

102. The Department’s mandate allows for the collection and use of sensitive personal information. It has an obligation to protect this information from the time it is obtained until it is destroyed by an approved method. We expected to find that records were disposed of in a manner that did not place Veterans’ privacy at risk. We examined the Department’s disposal practices and its outsourcing arrangements with private sector shredding companies.

103. The federal government purchases computers annually to replace obsolete equipment. Surplus computers are disposed of through various channels. Functional computer equipment is either donated to the Computers for Schools program or sold through Public Works and Government Services Canada’s Crown Assets Distribution Directorate. Regardless of the disposal method used, the originating department or agency is responsible for purging (wiping) the data stored in the memory of surplus assets.

104. Veterans Affairs Canada has established standard operating procedures to manage surplus electronic media, including computers, smart phones (e.g., BlackBerry devices), back-up tapes and other data storage devices. We found these procedures are followed consistently and include controls to ensure equipment is sanitizedFootnote 7 prior to disposal. We tested surplus computers during our site visits and verified they had been wiped.

105. However, we noted weaknesses in practices surrounding the disposal of paper records. Departments must ensure the destruction of documents is performed by individuals who have been security screened to the appropriate level, and that shredded material conforms to the size specifications prescribed under the Treasury Board security standard.Footnote 8 These specifications are intended to make the reconstruction of information on shredded paper impracticable.

106. With the exception of one district and two regional offices, the Department has outsourced the disposal of records to private shredding companies. We expected to find that the outsourcing arrangements were governed by written contracts, with terms and conditions to satisfy Government of Canada security requirements. We identified weaknesses in this regard; approximately one-third of the arrangements are informal (no contracts are in place). Others are subject to vendor–client agreements that are silent on shredding specifications and the security clearances required by those performing the destruction services.

107. There is also an absence of monitoring activity to verify that Veterans’ records are destroyed in a secure manner. Of the 25 sites that have records shredded on-site, 10 reported that the process is not monitored. We also confirmed that the Department does not systematically monitor contractors’ off-site disposal practices through periodic inspections. As a result, there is no assurance that:

- individuals handling client information possess the required security clearance;

- client records are destroyed in a manner such that they cannot be reconstructed; and

- information is disposed of on a timely basis to mitigate the risk of unauthorized access.

108. Compliance monitoring is critical for any outsourcing arrangement that involves personal information. The Department has not exercised due diligence in this regard. It assumes that contractors’ off-site disposal practices comply with Treasury Board security requirements without the necessary assurances.

109. The responsibility for ensuring inspections are carried out should be established and communicated within the Department. Without clear accountability and enforcement, third party service providers may circumvent their obligations without consequence.

110. Finally, an administrative infrastructure that tracks the entire destruction process is necessary in order to measure compliance with sound disposal practices. A number of current arrangements do not require shredding companies to submit a signed declaration to Veterans Affairs Canada that specifies the date the records were destroyed. This declaration is commonly referred to as a certificate of destruction. Requesting certificates of destruction, ensuring written contracts are in place and undertaking systematic monitoring activities would demonstrate the Department has taken reasonable steps to ensure Veterans’ records are destroyed securely.

111. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should ensure that written contracts are established for all outsourcing activities related to the disposal of personal information, with terms and conditions included therein to meet Treasury Board requirements.

To provide assurance that privacy and security requirements are met in a consistent manner, the Department should also monitor the on-site disposal of records and implement a protocol for monitoring contractors’ off-site destruction practices.

Department’s response:

Agreed. By October 2012, all contracts issued for shredding services will include uniform shredding and disposal specifications, as well as monitoring provisions, which meet or exceed the Department’s security standards and Treasury Board requirements.

Privacy Management and Accountability

112. A privacy management program refers to the structures, policies, procedures and processes in place to ensure a government institution meets its obligations under the Privacy Act. Core elements include effective governance, clear accountability, a privacy breach protocol, a process for the identification and management of privacy risks, and awareness training.

113. Veterans Affairs Canada has embarked on a number of initiatives to establish and maintain an understanding of privacy throughout the Department. Information management and privacy experts have been engaged to examine and identify opportunities for improving how the Department manages personal information. Investments have also been made in refining system access controls, employee awareness training, and the development of new policies, guidelines and processes to protect Veterans’ privacy.

Accountability for compliance with the Privacy Act is well established

114. To meet the obligations established under the Privacy Act, accountability for compliance with the Act must be well defined. In previous audits of other federal institutions, we noted that responsibility for overseeing compliance with the Act had not been assigned to a senior departmental official. As a result, we found gaps in the coordination and implementation of privacy-related responsibilities.

115. Recognizing that a gap existed, and as part of its efforts to create a privacy-conscious culture, Veterans Affairs Canada implemented a new governance structure to oversee privacy management. A chief privacy officer (CPO), reporting directly to the deputy minister, was appointed in 2011. The CPO is responsible for overall strategic direction and privacy compliance at the executive level, and oversees ongoing privacy-related activities within the Department.

116. The Departmental Privacy Committee was also established. It is chaired by the CPO and includes senior executives from all service and program areas. Committee members are responsible for bringing forward activities and planned changes within their areas of responsibility that may have privacy implications. These are examined by the Committee as a whole to ensure there is a coordinated and consistent approach to managing privacy in day-to-day operations. The Committee is also responsible for providing advice on privacy matters, approving privacy-related policies and processes, overseeing privacy impact assessments, and establishing departmental privacy priorities.

117. The CPO and the Departmental Privacy Committee are supported by the Department’s Access to Information and Privacy Coordinator and staff within the Privacy Policy Unit. These individuals have a critical role in the privacy management program. They act as privacy advocates and educators, and are arguably the leading authorities in terms of the Department’s compliance with the Privacy Act and associated policies and directives.

118. When considered collectively, the above provides a strong and integrated privacy governance regime. It incorporates key elements of sound privacy management: strategic planning, risk management and assurance of compliance. The Department is well positioned to move from reacting to privacy issues to proactively addressing them.

Privacy risk assessment process has been formalized

119. In 2002, the Treasury Board Secretariat introduced a policy on Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) to ensure privacy principles were considered for all new or substantially redesigned programs and services. The policy was replaced with a PIA directive in April 2010. Compliance with the directive depends on the presence of mechanisms for reporting on activities that may require privacy impact analysis.

120. A PIA is a tool that helps determine whether an initiative raises privacy risks. It also forecasts the probable impacts of the risks and proposes remedies to mitigate or eliminate them. By design, a PIA provides valuable analysis at an early stage, thereby reducing the risk of having to terminate or modify a program or service after implementation in order to protect privacy.

121. The Department has implemented a comprehensive framework for conducting a PIA. In addition to an overarching PIA policy, a formalized process is in place to facilitate a systematic approach to analyzing privacy risks. It outlines roles and responsibilities, and provides steps to follow in determining the requirement for a PIA, for conducting the assessment and for undertaking any post-PIA activities.

122. Based on our review of documents and interviews with staff engaged in the PIA process, we conclude that a formal infrastructure is in place to support the objectives and requirements of Treasury Board Secretariat’s Directive on Privacy Impact Assessment. Responsibilities and accountabilities for ensuring compliance with the Directive are well defined and communicated within the Department.

Mechanisms for reporting on and investigating privacy breaches are in place

123. The Treasury Board Secretariat’s Directive on Privacy Practices requires institutions to establish a plan for addressing privacy breaches. We expected to find a protocol in place to meet Treasury Board’s expectations.

124. Treasury Board defines a privacy breach in the following terms:

“A privacy breach involves improper or unauthorized collection, use, disclosure, retention and/or disposal of personal information…A breach may be the result of inadvertent errors or malicious actions by employees, third parties, partners in information-sharing agreements or intruders.”Footnote 9

125. In March 2011, Veterans Affairs Canada established a protocol to address privacy breaches. The process is outlined in the Department’s Privacy Breach Policy and Privacy Breach Guidelines. These are designed to educate employees and contract staff on privacy breaches, define their roles and responsibilities should a breach occur, and provide direction for a quick and effective resolution. The protocol incorporates four key steps: (1) breach containment and preliminary assessment; (2) evaluation of the risks associated with the breach; (3) notification; and (4) prevention.

126. Should employees or contract staff become aware of circumstances that suggest a Veteran’s privacy has—or may have—been compromised, they are instructed to report it immediately to their supervisor (or in the case of contractors, the project authority). The Guidelines also stipulate that any known or suspected privacy breach should be recorded on a Security Incident Report and forwarded to the Department’s head office for investigation.

127. Many privacy breaches are also categorized as security incidents. For example, the loss of a portable storage device or briefcase is considered a security incident; it becomes a privacy breach if it is determined the device or briefcase contained personal information. As a result, many breaches are reported to the departmental security officer (DSO). The DSO is responsible for ensuring the access to information and privacy (ATIP) coordinator is notified of all security-related matters that impact the privacy of individuals. We confirmed—through interviews and file examinations—that the DSO and ATIP coordinator collaborate on an ongoing basis.

128. Efforts to contain a privacy breach are generally coordinated at the local level where the breach occurred. We were told that all breaches are analyzed for the purpose of identifying and addressing the root cause. Resolution of the root cause may not be necessary if the incident is unlikely to reoccur or there is insufficient information to assess the cause despite reasonable efforts. There may also be occasions where the root cause is resolved at the breach containment stage. If an investigation revealed that a breach was the result of a policy, procedural or process weakness, corrective measures would be implemented.

129. A comprehensive approach to reporting privacy breaches can assist departments to better manage privacy risks, allowing them to adjust their policies, processes and practices based on lessons learned. Although the Department’s protocol provides a framework for doing so, we found evidence of privacy breaches that were not reported to head office and/or the ATIP coordinator. The ATIP coordinator is responsible for compiling statistical data on privacy breaches and reporting issues and trends to the chief privacy officer on an ongoing basis. It is difficult for the ATIP coordinator to perform this role without assurance that all breaches that impact Veterans’ privacy are fully reported and reviewed.

130. Recommendation

Veterans Affairs Canada should reinforce the requirement for employees and contract staff to report all known or suspected privacy breaches.

In addition, the access to information and privacy coordinator, in collaboration with the departmental security officer, should implement a system to consolidate all privacy-related breaches into one reporting tool.

Department’s response:

Agreed. As part of its Privacy Action Plan 2.0, issued in May 2012, Veterans Affairs Canada is strengthening its management of privacy incidents and breaches. As part of this effort, the Department will highlight its Privacy Breach Policy and introduce new online tools and information for staff.

In addition, the Department is currently participating in a pilot project through the Treasury Board Secretariat to develop standard tools for managing privacy breaches. The Department will also consolidate all privacy-related breaches into one reporting tool.

All of these activities will be complete by December 2012.

New process is designed to ensure contracts include adequate privacy provisions

131. Institutions subject to the Privacy Act are accountable for personal information under their control. Contracting out a program or service-delivery function does not relieve an institution of its privacy obligations under the Act or related Treasury Board policies and directives.

132. Veterans Affairs Canada has entered into contracts and agreements with third parties to facilitate the delivery of programs and services. National contracts have been established for vocational rehabilitation, career transition services and processing of health claims. In addition, there are contracts for various medical requirements—such as services provided by physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, dentists and clinical consultants—and agreements with long-term care facilities. The Department has also engaged the services of a number of medical equipment suppliers.

133. We extracted a sample of 17 contracts for review, including the three national contracts. We expected to find that they contained adequate provisions to protect Veterans’ personal information, and the service providers’ obligations in that regard were clearly defined.

134. The three national contracts include many sound privacy and security provisions, although a requirement to report privacy breaches is absent in two of them. With one exception, the medical advisory services, nursing and occupational therapist contracts provide a framework for ensuring personal information is adequately protected and managed in accordance with fair information practices.