Investigation of unauthorized disclosures and modifications of personal information held by Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada resulting from cyber attacks

Special report to Parliament

February 15, 2024

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

Toll-free: 1-800-282-1376

Phone: 819-994-5444

TTY: 819-994-6591

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada 2024.

Cat. No.: IP54-116/2024E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-69966-0

Letter to the Speaker of the Senate

BY EMAIL

February 15, 2024

The Honourable Raymonde Gagné, Senator

Speaker of the Senate

Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Madam Speaker,

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Special Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada entitled Special Report to Parliament: Investigation of unauthorized disclosures and modifications of personal information held by Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada resulting from cyber attacks. This tabling is done pursuant to section 39(1) of the Privacy Act.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Philippe Dufresne

Commissioner

Letter to the Speaker of the House of Commons

BY EMAIL

February 15, 2024

The Honourable Greg Fergus, M.P.

Speaker of the House of Commons

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker,

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Special Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada entitled Special Report to Parliament: Investigation of unauthorized disclosures and modifications of personal information held by Canada Revenue Agency and Employment and Social Development Canada resulting from cyber attacks. This tabling is done pursuant to section 39(1) of the Privacy Act.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Philippe Dufresne

Commissioner

Introduction

Federal government departments and agencies hold vast amounts of sensitive information, including the personal information of millions of Canadians, which make them attractive targets for cyber attacks. This is why it is essential that they have robust safeguards in place to mitigate against data breaches.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) has concluded an investigation into 25 federal departments and agencies, including Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), regarding a major breach that offers lessons for other institutions. The breach compromised the sensitive financial, banking, and employment information of tens of thousands of Canadians, leading to numerous cases of fraud and identity theft.

The investigation found that attackers used, among other things, the CRA’s sign-in portal and ESDC’s “GCKey” authentication service to infiltrate their online services and access individuals’ online accounts using stolen credentials (such as login information and passwords) that were obtained from previous breaches. Attackers used a technique known as credential stuffing, which allowed them to access, modify and create new online accounts in these stolen identities to fraudulently redirect government benefit payments to other bank accounts.

The investigation found that both organizations had under-assessed the level of identity authentication that was warranted for their online programs and services given the sensitivity of personal information involved. Moreover, ESDC and CRA had not taken the necessary steps to promptly detect and contain the breach, due in part to inadequate security assessments and testing of its authentication and credential management systems, and limited accountability and information sharing between departments.

Both organizations have agreed to implement the OPC’s recommendations, which include improving communications and decision-making frameworks to facilitate the implementation of efficient safeguards against future attacks and rapid response to privacy breaches, as well as conducting regular security assessments.

About this Special Report

Under the Privacy Act, OPC Reports of Findings may only be shared publicly in a special report or annual report. In order to ensure more timely reporting, the Privacy Commissioner has included the findings in the following investigation in this Special Report to Parliament.

Overview

In August 2020 the federal government publicly announced that attackers using credential stuffing had gained access to certain Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”) online accounts and other departments’ online accounts accessible via the Government of Canada’s (“GC”) centralized “GCKey” authentication service and CRA’s own login portal. The cyber-attacks focused on accessing and modifying personal information held by CRA and Employment and Social Development Canada (“ESDC”) for financial gain. The attacks successfully compromised the sensitive personal information of tens of thousands of Canadians.

Given that personal information under their control was breached, ESDC and CRA both contravened the section 8 disclosure provisions of the Privacy Act (“Act”). A contravention of section 8 does not, in and of itself, mean that an organization did not take adequate steps to protect privacy, however, in this matter, our investigation found that neither department had adequate protections in place to prevent the disclosures that occurred. Further, neither department took all reasonable steps to protect against unauthorized modifications to personal information by attackers – representing contraventions by both departments of the subsection 6(2) accuracy provisions of the Act.

Specifically, we found that both ESDC and CRA under-assessed the level of identity authentication warranted given the elevated sensitivity of the personal information accessible online via their platforms. Further, they both had inadequately informed and accountable security decision-making prior to the breach, due to a siloed approach to interdepartmental accountability and information sharing as well as inadequate assessments and testing of security. Finally, both departments lacked adequate monitoring, supported by effective interdepartmental coordination, to detect and promptly contain the ongoing breach.

Both departments, as well as Treasury Board Secretariat (“TBS”) and other GC departments playing a central role in security safeguards, have since implemented corrections. However, we found that certain safeguard weaknesses persist and remain unresolved. To this end, we made recommendations related to: (i) improved authentication practices, (ii) coordinated and collaborative accountability for security decision-making, and (iii) effective monitoring.

CRA accepted our recommendations. ESDC likewise accepted our recommendations, although in one case conditional on the availability of funding. On that point, we would expect ESDC to take the steps necessary to ensure that security measures to protect the privacy of Canadians are appropriately prioritized, resourced and implemented.

Background

- At the time of the attack, CRA and ESDC had a system in place (“e-link”) that allowed individuals who logged in via ESDC’s portal to freely access accounts held in that individual’s name at CRA and vice versa without any additional authentication. Given that the two departments effectively shared safeguards, compliance with the Act in relation to these incidents is examined jointly in this report.

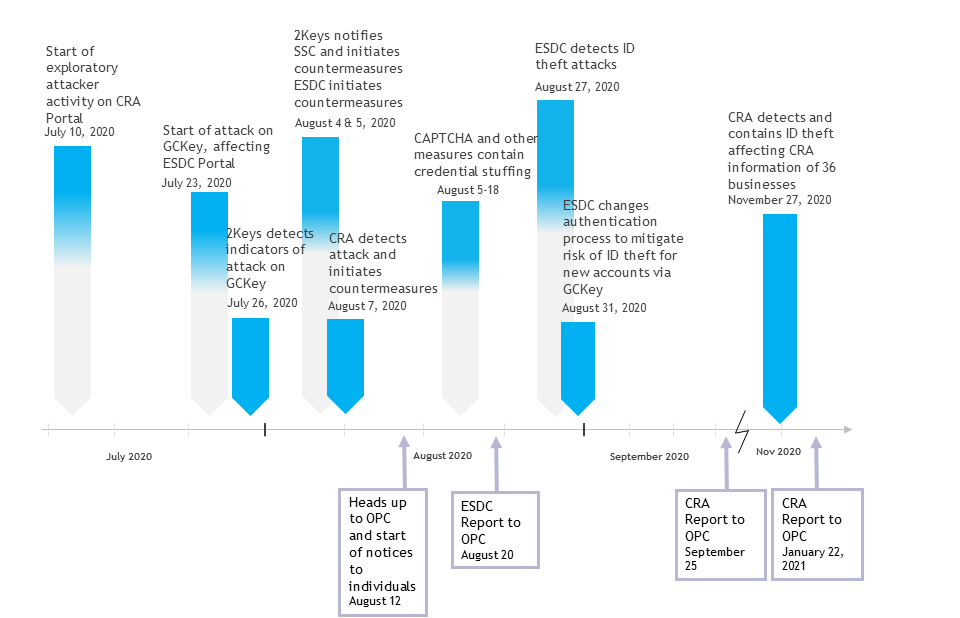

Breach timeline

Text version of Figure 1

Breach timeline

July 10, 2020 – Start of exploratory attacker activity on CRA Portal

July 23, 2020 – Start of attack on GCKey, affecting ESDC Portal

July 26, 2020 – 2Keys detects indicators of attack on GCKey

August 4 & 5, 2020 – 2Keys notifies SSC and initiates countermeasures ESDC initiates countermeasures

August 7, 2020 – CRA detects attack and initiates countermeasures

August 12, 2020 – Heads up to OPC and start of notices to individuals

August 5-18, 2020 – CAPTCHA and other measures contain credential stuffing

August 20, 2020 – ESDC Report to OPC

August 27, 2020 – ESDC detects ID theft attacks

August 31, 2020 – ESDC changes authentication process to mitigate risk of ID theft for new accounts via GCKey

September 25, 2020 – CRA Report to OPC

A marking in the timeline to indicate a related breach was detected at CRA

November 27, 2020 – CRA detects and contains ID theft affecting CRA information of 36 businesses

January 22, 2021 – CRA Report to OPC

- According to information from the investigations conducted by the GC departments involved, a credential stuffing attack on ESDC’s online services began on approximately July 23, 2020, via ESDC’s Enterprise Cyber Authentication Solution and Canada Student Loan systems (“ESDC’s portal”). ESDC’s portal uses Shared Services Canada’s GCKey Service, which is operated by 2Keys Corporation (“2Keys,”) under the direction of Shared Services Canada (“SSC”).Footnote 1 Another credential stuffing attack - on CRA’s online service accounts via CRA’s Authentication Management System/Credential Management System (“CRA’s portal”) - commenced with reconnaissance activities on approximately July 10, 2020, followed by automated (bot) login activity beginning approximately July 26, 2020. In the case of CRA’s portal, the attackers initially exploited a 20-month-old misconfiguration in CRA’s system. The misconfiguration allowed them to bypass CRA’s requirement for users to answer a security question when logging in from a new device. ESDC’s portal did not have this requirement at the time, and thus did not require such a bypass. After CRA fixed the misconfiguration, attackers renewed their credential stuffing attack on CRA’s portal by “stuffing” usernames, passwords, and answers to security questions.

- Credential stuffing is where attackers, usually using bots, use stolen credentials obtained from previous breaches at other organizations, to access existing online accounts. This attack technique leverages individuals’ tendency to reuse usernames and passwords.Footnote 2

- In addition, 2Keys alerted ESDC to new accounts that appeared to have been created by the attackers. This alert led ESDC, beginning August 27, 2020, to discover over 2,000 cases of identity theft.

- Identity theft is where attackers use identifying information obtained from other sources to successfully pass an organization’s identity validation processes for new applicants (i.e., ones that do not already have credentials with the organization).

- In this breach attackers were able to fraudulently apply for new benefits at ESDC and create new accounts in individuals’ names without their knowledge. In November 2020, CRA also separately discovered a case of identity theft where attackers successfully created new credentials for a CRA represent-a-client account, and subsequently accessed information of 36 businesses, including over 8000 individuals’ sensitive personal information.

- In total, attackers used approximately 26,000 CRA “My Accounts”, one CRA “Represent a Client” account, 6000 ESDC “My Service Canada Accounts,” and 112 ESDC business accounts to access the: (i) contact information, (ii) identifiers, [including social insurance numbers (“SINs”) and dates of birth] and (iii) sensitive financial, banking and employment information of 14,000 individuals held by ESDC and of 34,000 individuals held by CRA.Footnote 3

- Attackers also used the unauthorized access to modify personal information in accounts - changing direct deposit and address information to redirect existing payments to the attackers, as well as applying for new benefits such as the pandemic Canada Emergency Response BenefitFootnote 4 (“CERB”), Employment Insurance (“EI”) benefits, and tax refunds.

OPC Notification

- CRA and ESDC provided verbal heads-up of the breaches to our Office (“OPC”) on August 12, 2020. ESDC subsequently sent a preliminary breach report to our Office on August 20, 2020, with an update on November 19, 2020. Despite mandatory breach reporting to OPC under the TBS Directive on Privacy Practices, the CRA delayed its preliminary breach report to OPC until September 25, 2020, stating at the time that notification to impacted individuals was their priority over providing information to OPC.

- On December 8, 2020, CRA provided a notice to OPC about the identity theft described in paragraph 6 but did not provide details via a completed breach report until January 22, 2021.

- Of additional concern, during the final stages of investigation, we learned that other breaches, which the CRA does not connect to the credential stuffing attack, had been detected in 2020 and never reported to OPC. OPC is following up separately with CRA on this matter. Preliminary information indicates that up to 15,000 individuals could have been similarly affected by these breaches which were, like the breach examined in this report, related to CERB fraud.

- Since October 2022, the TBS Policy on Privacy Protection requires government institutions to report material privacy breaches to OPC and TBS within seven days.

Methodology

- OPC based its conclusions on written submissions and interviews with ESDC and CRA, the subjects of this investigation, as well as information from staff at SSC, 2Keys, TBS and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (“CCCS”), who play central roles with respect to GCKey and overall GC security.Footnote 5 The receipt of written representations from CRA, ESDC, SSC and TBS was often delayed by weeks or months, or was incomplete, requiring multiple exchanges and escalations between increasingly senior executives. Additionally, material such as the GCKey Credential Stuffing Attack: Lessons Learned Report, jointly prepared by SSC and TBS, was initially withheld from OPC under a claim of solicitor client and litigation privileges despite being a mandatory report under the GC Cyber Security Event Management Plan (“GC CSEMP”).Footnote 6 ESDC and CRA also prepared lessons-learned / post-mortem reports, which they would not provide to OPC due to claims of privilege. ESDC and TBS cited a class action lawsuit related to the breach as a factor in the delays. ESDC further attempted to restrict OPC’s access to interview individuals citing privilege. Ultimately, notwithstanding the described delays, we were able to conduct relevant interviews and otherwise obtain the information we deemed necessary to advance and conclude our investigation.

Analysis

Personal information was not adequately protected from disclosure and modification

ESDC and CRA took inadequate steps to prevent the unauthorized access

- Section 8 of the Act specifies that a department must not disclose personal information “under its control” except in limited circumstances. OPC’s position is that where a department suffers a breach of personal information that results in information being accessed and disclosed, without justification under subsection 8(2) of the Act, then there is a contravention of section 8. Both CRA and ESDC acknowledge that the attacks in this instance led to unauthorized disclosure of personal information under their control. As a result, we find that both departments contravened section 8 of the Act.

- Notwithstanding the above, a contravention of section 8 does not, in and of itself, mean that an organization did not take adequate steps to protect privacy. However, as detailed in this report, we determined that in this matter neither department took adequate steps to protect and prevent the disclosures of the breached information, given its elevated level of value and sensitivity.

ESDC and CRA did not take all reasonable steps to ensure accuracy of personal information

- Subsection 6(2) of the Act requires a government department to take all reasonable steps to ensure that personal information that is used for an administrative purpose by the department is as accurate, up-to-date and complete as possible. In these breaches, by successfully being validated by the authentication steps that ESDC and CRA had in place, attackers were able to introduce inaccurate personal information into CRA and ESDC systems that was then used to make decisions about individuals, for example, the issuance of CERB benefits in their name.

- As described in the Treasury Board Directive on Privacy Practices section 4.2.15 and 4.2.16, reasonable steps to ensure accuracy include: “…collecting personal information directly from the individual… [or] [i]mplementing…measures to: (1) [e]nsure that the personal information is obtained from a reliable source; or (2) [v]erify or validate the accuracy of the personal information before use.” A level of authentication is essential to confirm that the information collected is not from an imposter, but rather comes from the individual themselves or a reliable source where there is an elevated risk of malicious modification.

- We determined that, at the time of the breach, CRA and ESDC were not taking all reasonable steps, as required by subsection 6(2), to ensure the accuracy of the personal information that they used for administrative purposes – as detailed in the remainder of this report.

Sensitivity of personal information warranted significant safeguards and mitigation measures

- In our investigation we examined CRA and ESDC’s safeguards against unauthorized access and modification in light of the sensitivity of the personal information in question. The personal information held in, and modifiable through, online CRA and ESDC individual and business accounts included:

- Extensive personal identifiers including SINs and dates of birth, and

- Detailed financial and employment history information included on: tax returns, records of employment (“ROEs”), pension, EI, Old Age Security and CERB benefit statements, loans and grants records for students and unemployed individuals, and direct deposit information.

- The online portals similarly allowed for significant modification to personal information held by CRA and ESDC through existing or new accounts, including modifying address, contact and banking information, and the ability to apply for tax refunds and the range of benefits above.

- The risk of harm to individuals from unauthorized disclosure and modification is high, taking the form of the sustained risk of identity theft, as well as the immediate potential for loss of thousands of dollars of benefits or tax refunds, or being held liable for thousands of dollars of fraudulent benefit claims or tax filings. These risks are real. Malicious actors can benefit from the fraud that creates these harms. These risks also result in associated privacy harms including the psychological stress of being victimized (potentially for years) by identity theft.

- To illustrate, in late 2022, the OPC received a complaint against ESDC from an individual who was the victim of identity theft at ESDC in 2020. From late November to December 2020 attackers applied for fraudulent EI benefits and opened an online account at ESDC in his name. Over the next two years they were able to repeatedly apply for benefits in his name without being detected by ESDC. When the individual later lost his job and needed EI benefits himself, he was unable to obtain them as he was told that he had already received his maximum benefits. Further, he was later held liable by ESDC and CRA to pay taxes on those fraudulent benefits.

- In the wake of the breach, in recognition of the potentially serious harms to individuals from the compromise of this sensitive personal information, CRA and ESDC worked to detect and mitigate the negative impact on individuals from these breaches, including: (i) reversing fraudulent changes and notifying affected individuals, (ii) offering credit monitoring services, and (iii) working with individuals affected by identity theft or fraud to help them clear their name.

- However, in the specific case described above, the individual suffered for many stressful months trying to obtain assistance to rectify the issue from CRA and ESDC. He was first unable to access benefits he was entitled to during a time of financial hardship and then found himself under threat of garnishment of wages to pay taxes on the fraudulent benefits. The matter was only addressed and corrected after the OPC got involved. ESDC has since committed to determining the cause of the delay for the complainant’s issues to be actioned by ESDC, and to implementing a strategy to avoid recurrence.

- This case highlights that negative impacts from breaches can be persistent, and organizations have accompanying obligations to dedicate sufficient resources for long-term risk mitigation for individuals. The case also highlights why the information in question is of an elevated sensitivity and warrants commensurate safeguards to protect against unauthorized modification and disclosure. These are safeguards, that as detailed below, CRA and ESDC did not have in place.

Main Deficiencies

- The main deficiencies in the steps taken by ESDC and CRA to prevent the unauthorized disclosures and modifications were as follows:

- Under-assessment of the level of identity authentication warranted;

- Inadequately informed and accountable security decision-making; and

- Lack of effective monitoring, supported by effective interdepartmental coordination, to detect and promptly contain the ongoing breach.

Deficiency 1: Under-assessment of level of identity authentication warranted

- A key deficiency identified in our investigation was the under-assessment, by both ESDC and CRA, of the level of identity assurance (to guard against identity theft) and credential assurance (to guard against credential stuffing or other credential-related risks) warranted for their online services. This led them to select inadequate authentication practices which the attackers were able to exploit to access and modify personal information.

- Assessing the appropriate level of identity assurance involves determining the required level of confidence that someone applying for a new account/service or new credentials is who they say they are. Assessing the appropriate level of credential assurance (that follows the initial identity verification stage) involves determining the required level of confidence that someone accessing an existing account with credentials (such as a username and password) is who they say they are.

- The GC Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements, sets out four “levels of assurance” to guide departments in determining both identity assurance and credential assurance practices:

| Level | Identity Assurance | Credential Assurance |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Very high confidence required that an individual is who he or she claims to be. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause serious to catastrophic harm. | Very high confidence required that an individual has maintained control over a credential that has been entrusted to him or her and that that credential has not been compromised. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause serious to catastrophic harm. |

| 3 | High confidence required that an individual is who he or she claims to be. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause moderate to serious harm. | High confidence required that an individual has maintained control over a credential that has been entrusted to him or her and that that credential has not been compromised. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause moderate to serious harm. |

| 2 | Some confidence required that an individual is who he or she claims to be. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause minimal to moderate harm. | Some confidence required that an individual has maintained control over a credential that has been entrusted to him or her and that that credential has not been compromised. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause minimal to moderate harm. |

| 1 | Little confidence required that an individual is who he or she claims to be. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause minimal to no harm. | Little confidence required that an individual has maintained control over a credential that has been entrusted to him or her and that that credential has not been compromised. Compromise could reasonably be expected to cause minimal to no harm. |

- Both CRA and ESDC assessed the level of assurance for all the affected online services (including business and representative accounts giving access to many individuals’ personal information) as being a level 2.

- Appendices A and B of the GC Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements provide descriptions of harms for each level (see relevant excerpts in Annex A of this report). Examples of potential financial harms for level 2 are described as ones having no impact or only an insignificant material impact on an individual while level 3 is described as ones having a “significant material impact”. Examples of psychological distress at level 2 are those not requiring treatment by first-aid personnel or health care professionals, while examples at level 3 are those requiring some kind of treatment (first-aid or otherwise).

- In our view a potential loss of thousands of dollars to an individual would constitute a “significant material impact”, and the risk of sustained identity theft and associated psychological harms to a single individual could reasonably be expected to require ‘first aid’ level mental health services. In past investigations including this matter, victims have noted enduring psychological harms resulting from said violations. Therefore, we find that both CRA and ESDC should have assessed that their online services in question warranted level 3 identity assurance and credential assurance.

- The under-assessment by both ESDC and CRA in this case led to the implementation of inadequate authentication processes at ESDC and CRA to guard against the identity theft and credential stuffing that occurred at both departments during these breaches.

Identity Assurance practices by ESDC and CRA inadequately protected against identity theft

- Under the TBS Guideline on Identity Assurance, level 2 identity assurance requires the collection of only one piece of evidence of identity and does not require any steps to verify the “linkage” of identity information to the applying individual. For level 3, among other requirements, two pieces of evidence of identity must be collected, one of which must be foundational, such as records of birth or citizenship, and linkage must be confirmed, though acceptable linkage methods are not described in detail.

- The NIST Digital Identity Guidelines, an internationally accepted standard in place since 2017, is more specific. It describes that where potential harm from compromise could have a “moderate”Footnote 7 impact, among other steps, verification of linkage to a strong piece of identity evidence shall be undertaken using physical or biometric comparison of the applicant to the proof of identity, either remotely or in person. The Guidelines specify that knowledge-based verification alone (i.e., something the applicant knows) should not be used. The Guidelines further specify that in addition to linkage verification, address confirmation should be done by sending an enrollment code or notification to a postal address that has been validated in records (i.e., not newly supplied by the applicant).Footnote 8

- At the time of the breach, ESDC’s identity assurance process to create new accounts did not meet either standard given the level of potential harm that could result from unauthorized access and/or modification of personal information under its control.Footnote 9

- It did not require that applicants provide documentary or digital evidence of identity (foundational or otherwise) or verify linkage using physical or biometric comparison. It required only that individuals obtain a numerical codeFootnote 10 from ESDC by providing an accurate SIN, date of birth, full name, and mother or father’s last name at birth (which ESDC is able to validate against its SIN records). Attackers exploited this weak authentication to create more than 2,000 fraudulent accounts that were only detected by ESDC after 2Keys notified them that the attackers appeared to have created new GCKey credentials.

- Similarly, we learned in the final stages of the investigation, that at the time of the breach, CRA’s identity assurance steps for individuals who wished to sign up for a new ‘represent-a-client’ account or create entirely new credentials to access an existing ‘represent-a-client’ account, also did not meet either standard.

- CRA’s related identity assurance process likewise required only that the applicant provide knowledge of personal identifiers (including name and SIN) and the code from the previous year’s personal tax notice of assessment (which CRA could validate against its records).

- CRA detected, in November 2020, that attackers exploited this weak identity assurance process to fraudulently create new credentials for an existing ‘represent-a-client’ account, where they could have accessed the personal information of existing business clients.Footnote 11 The impact of this weakness was compounded by the fact that individuals with a ‘represent-a-client’ account could, at the time, gain access to personal information of new business clients using weak single factor authentication to confirm that the representative was authorized by the business. In this case attackers were able to exploit these weaknesses to access more than 8000 individuals’ sensitive personal information associated with 36 businesses.

- CRA confirmed that its identity assurance processes were exploited in 2020 by threats outside of this case, causing breaches leading to CERB fraud, which at the time, went unreported to the OPC. We are following up separately on this matter.

- In the wake of the breaches examined in this report, CRA and ESDC added address confirmation (sending an enrollment code to the address on record from previous tax filings) to their identity assurance processes in question.Footnote 12 However, to our knowledge, neither is requiring the collection of evidence of identity from applicants or verifying linkages between identity claimed and the actual identity using physical/biometric comparison or equivalently robust methods.

- Further, ESDC did not apply these improvements to accounts created using SecureKey ConciergeFootnote 13 credentials until mid 2021, when it began to offer a second identity assurance authentication process, leveraging identity verification of individuals already conducted by certain Canadian financial institutions.Footnote 14 In the interim, attackers continued to be able to exploit this vulnerability in ESDC’s identity assurance process, including the identity theft incident experienced by the individual who later complained to OPC as described in paragraph 22 above.

- In addition, to our knowledge, ESDC continues to permit identity assurance without the collection of any piece of identity, or the verification of linkage or address confirmation for certain online services.

Recommendation A – Identity Assurance

- We therefore recommended, in order to satisfy its accuracy obligations under section 6(2) of the Act, that within 6 months, ESDC and CRA alter their identity assurance practices, for all of their online services, to adopt practices, aligned with internationally accepted standardsFootnote 15 for identity assurance in cases where moderate harm could result.

- CRA accepted the recommendation. ESDC also accepted the recommendation, committing to working with TBS to explore the feasibility of further enhancements to its identity assurance practices, particularly examining international standard(s). It claimed that collaboration with TBS is necessary as TBS sets the identity assurance policies for the GC.

- TBS noted that it has developed an assurance level requirement tool to support departmental assessment activities. However, the tool does not provide further details about expected identity assurance practices. During the course of the investigation TBS agreed that it will, in collaboration with CCCS examine its guidance and tools and provide increased clarity to departments on identity assurance practices, in keeping with internationally accepted standards for sensitive personal information.

- We therefore find the disclosure and accuracy matters, as they relate to identity assurance by CRA and ESDC, to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

Credential Assurance practices by ESDC and CRA inadequately protected against credential stuffing

- As explained in paragraph 28, while “identity assurance” validates someone’s identity when they create a new account or new credentials with an organization, “credential assurance” refers to the steps taken to ensure that the person accessing an existing account, with existing credentials (like username and password), is authorized to do so.

- Under GC guidelines, level 2 credential assurance requires only single factor authentication (e.g., “something you know” – such as passwords), while level 3 credential assurance requires multi-factor authentication (“MFA”) (e.g., “something you know” plus “something you have” - like a one-time code sent to a phone number registered to the user). This is consistent with internationally accepted standards such as NIST Digital Identity Guidelines which has, since at least 2017, recommended MFA for credential assurance for cases where compromise could result in more than “insignificant or inconsequential financial loss to any party.”

- Neither ESDC nor CRA had credential assurance practices appropriate to the sensitivity of the personal information in question as they had only single factor authentication in place.

- Further, CRA and ESDC’s standard account recovery authentication measures in place at the time of the breach enabled users to access accounts without a password (using forgotten-password mechanisms) by answering pre-established security questions. No evidence was provided to either confirm, or eliminate the possibility that, attackers gained unauthorized access via CRA or ESDC’s standard account recovery processes. However, “pre-registered knowledge” such as the answers to security questions, have long been known to be a particularly weak type of single factor authentication, that is not only vulnerable to theft via data breaches, but is also guessable and predictable. GC guidelines on authentication are silent on account recovery authentication procedures. That said, by the late 2010s, using security questions alone, as was CRA and ESDC’s practice, was not considered to be an adequate authentication measure, even in cases where single-factor authentication was considered adequate, which it was not in this matter.Footnote 16

Common practice does not necessarily equate to compliant practice

- In response to our Preliminary Report, CRA asserted that at the time of the incidents, MFA was not a common practice for any organization in Canada where like information was stored. We acknowledge that in 2020 when this breach occurred, it was still common practice to protect individuals’ accounts, giving access to one person’s personal information, via single factor authentication. However, common practice or industry standard does not necessarily equate to compliant practice.

- In addition to the GC guidance and NIST guidance referenced above, CCCS indicated that leading up to the breach, it was consistently recommending MFA both publicly as well as in discussions with institutions. It highlighted to OPC that several of its publications issued between April 2018 and June 2020, prior to the breach, recommended MFA, including the User authentication guidance for information technology systems (ITSP.30.031 v3), Best practices for passphrases and passwords (ITSAP.30.032), and Secure your accounts and devices with multi-factor authentication (ITSAP.30.030). In the current environmental context of rapidly evolving threats and increased access to technology, where at minimum “moderate” harm to a single individual could result, single factor authentication should not be considered adequate to protect an individual’s privacy.

- Since the breach, both CRA and ESDC have implemented mandatory MFA for all their individual, business and representative accounts. In addition, CRA has implemented MFA for all account recovery processes and added further authentication measures to the process for businesses to authorize a new representative to access business accounts. Both ESDC and CRA also added additional security measures for high impact modifications to personal information, such as for changes to direct deposit information. Further, in response to a preliminary version of the report, TBS and SSC indicated that, as of September 1, 2023, SSC has implemented MFA capabilities, on an opt-out basis, for all departments using the GCKey service provided by 2Keys.Footnote 17

Recommendation B – Credential Assurance

- We recommended that within 12 months ESDC adopt account recovery authentication measures that rely on MFA for all its online services that enable access to, or modification of, personal information.

- ESDC accepted the recommendation, committing to work collaboratively with CRA to update and align account recovery authentication measures. We therefore find the disclosure and accuracy matters, as they relate to credential assurance by CRA and ESDC, to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

Deficiency 2: Inadequately Informed and Accountable Security Decision-making

- In addition to correctly assessing the level of assurance required, to ensure sound decision-making to protect personal information, those accountable must be well informed and included in decision-making processes. Under the Act, the Deputy Ministers of each department are ultimately responsible for compliance with the Act. This includes when using mandatory SSC infrastructure, such as GCKey, and when safeguards are partially outsourced to partners and third-party contractors as was the case here for both ESDC and CRA.Footnote 18

- Our investigation found that prior to the attacks, decision-makers within both CRA and ESDC were not adequately informed or involved in decision making about current threats and the effectiveness of current safeguards in place against those threats. We identified two issues that contributed to this problem: a) silos in interdepartmental information sharing and accountability systems and b) inadequate vulnerability assessments and penetration testing by CRA and ESDC.

Silos in interdepartmental information sharing and accountability systems

- Subject matter experts that we interviewed at ESDC, SSC and TBS indicated that they were not aware that credential stuffing was a substantial threat prior to this incident, despite the fact that by the late 2010s it was a significant attack vector. Appendix C of the GC Password Guidance published in 2018 noted the availability of previously stolen username and password databases for attacks, and in 2017 OPC issued a public warning about what was then a recent trend of breaches using this method. Other experts between 2017 and 2019 similarly highlighted this risk.Footnote 19,Footnote 20 CRA indicated it was aware of the threat of credential stuffing.

- SSC’s service provider for GCKey, 2Keys, also indicated it was aware of the risk of credential stuffing. However, in its role as a service provider to SSC it did not have visibility into how GCKey services were used and was unaware that departments were using GCKey to authenticate access to sensitive CRA and ESDC data.

- CCCS indicated that it was aware that credential stuffing attacks were a substantial threat in 2020. However, we did not find indications that it raised awareness about it with stakeholders prior to a brief reference to credential stuffing in Secure your accounts and devices with multi-factor authentication (ITSAP.30.030) issued in June 2020.Footnote 21 CCCS took the position that the credential stuffing attack via the GCKey service “was outside the scope of GC CSEMP [Government of Canada Cyber Security Event Management Plan],” for which it is mandated to play a cyber-security advisory role to departments. It stated that this was a result of the attack being carried out against third-party IT infrastructure and the fact that “the technology was not the target but rather the accounts of citizens using legitimate credentials.”

- TBS has since made positive high level policy changes in November 2022, when it published a revised GC CSEMP with enhancements in a range of areas including: roles and responsibilities for situational awareness of emerging threats and information sharing, as well as broadened categorization of cyber-security events to clearly include events such as credential stuffing. It continues to update GC CSEMP including an update on October 27, 2023.

- SSC similarly attempted to distance itself from accountability for the breach, asking that OPC refer to the matter only as “CRA and ESDC breaches” and never as a “GCKey breach.” It stated that the GCKey service (for which it is the technical owner and TBS is the business owner) was not “breached,” noting that nothing was stolen from GCKey itself, only from services GCKey was protecting. SSC indicated that GCKey was not designed to stop the credential stuffing attacks against the ESDC website and that GCKey was “performing as designed.”

- We disagree that GCKey was not breached, as the GCKey service should evidently not have been “designed” to permit malicious access. This is particularly the case as 2Keys reported that small scale credential stuffing attacks on the GCKey service were a regular occurrence by 2020, and it had flagged the vulnerability of the GCKey service to SSC in 2017 with a related proposal to offer multi-factor authentication (“MFA”) as an added protection.Footnote 22

- TBS declined to consider 2Keys’ unsolicited proposal, which would have cost a fraction of a dollar per GCKey account, citing that an active procurement process was underway at the time for a replacement for GCKey. Even though that process was later cancelled, SSC and TBS did not enable MFA in GCKey until after this breach (for two departments) and did not make MFA available as an opt-out feature for all departments until August 2023. Further, SSC did not institute other measures to reduce the risk of credential stuffing attacks on GCKey, such as implementing a CAPTCHA, until after the 2020 attack began.

- We did not receive evidence that ESDC and CRA (due to the e-link), who were ultimately accountable for the sensitive personal information of millions of Canadians available via the GCKey Service, were meaningfully included in the decision not to enable MFA in GCKey, or even aware of the related deliberations about the underlying risks highlighted by 2Keys. In our view SSC had a responsibility to keep partners relying on its infrastructure well informed about safeguard related matters, including issues that could result in compromise from known threats.

- In a similar pattern of a siloed approach to accountability, CRA and ESDC both argued, with respect to their accountability, that at the time of the breach they were simply following GC security policy, which TBS is ultimately accountable for developing and publishing.

- TBS in turn asserted that departments are responsible for implementing GC security policy requirements and that this includes responsibility for: “[i]dentifying security and identity management requirements for all departmental programs and services, considering potential impacts on internal and external stakeholders.”

- Shared security safeguards can be efficient and can improve useability and accessibility for users, but in order to ensure adequate protection and functionality, the shared safeguards must be accompanied by collaborative and informed accountability by all parties.

Lack of Comprehensive Vulnerability Assessments and Penetration Testing

- We also found gaps in systems for ensuring informed security decision-making within ESDC and CRA. Specifically, we found inadequate vulnerability assessments and penetration testing for both ESDC and CRA, and in addition, for CRA we found inadequate remediation for identified risks.

- Vulnerability assessments are systematic examinations of an information system or product to determine the adequacy of security measures, identify security deficiencies, provide data from which to predict the effectiveness of proposed security measures, and confirm the adequacy of such measures after implementation.

- Penetration testing is a manual simulated attack performed on a computer system to evaluate its security. Comprehensive penetration testing is a valuable tool to identify vulnerabilities, as it uses a broad menu of current threat tools and techniques known to be used by attackers, combined with manual expertise, to directly test security safeguards.

- Consistent with previous OPC investigations,Footnote 23 we would expect that organizations protecting significant volumes of sensitive personal information would annually (at minimum) conduct:

- a comprehensive internal assessment of the security of their online services, and at least every two years, a comprehensive external (i.e., independent) security assessment, and

- regular penetration testing, including annual comprehensive external (i.e., independent) penetration testing.

ESDC’s vulnerability assessments were not comprehensive and ESDC did not conduct penetration testing

- ESDC provided several security assessments for the deployment of new features and components of its online services. However, none of the assessments were scoped to evaluate its services from end-to-end. We continued to see awareness and accountability silos similar to those described in the previous section, with one assessment provided for the CRA-ESDC deposit and address sharing initiative (“DAISI” completed in June 2018), specifically indicating that: “The relevant SSC IT infrastructure components are unassessed. This is not unique to DAISI; all of ESDC’s systems and applications have significant reliance on SSC IT infrastructure. The uncertainty concerning the security posture of SSC provisions [sic] and manages for ESDC has continually presented a risk for ESDC.”

- Annual internal vulnerability assessments of GCKey were conducted by 2Keys and shared with SSC. However, ESDC did not receive these assessments. Further, given the limited scoping of the assessments, these would have provided an incomplete picture of vulnerabilities specific to the way ESDC’s online services operate – such as identity verification for new accounts. None of these assessments were independent external assessments, and neither ESDC nor SSC conducted any relevant penetration testing in the 3 years leading-up to the attack.

- ESDC indicated that with respect to CRA’s security safeguards (which it was using via the e-link), it relied on assurances from CRA that its safeguards were adequate. In our view ESDC had an obligation to proactively inform itself of relevant security threats and vulnerabilities of safeguards that it was relying on via CRA and SSC. This could take the form of conducting or contracting its own assessments and testing of these safeguards or ensuring that it routinely receives copies of adequate assessments, testing and reports on steps taken to adequately address risks highlighted. Any system of safeguards is only as effective as its weakest link, so a “trust but verify” approach is critical.

CRA’s vulnerability assessments were not sufficiently thorough or independent, its penetration testing was infrequent, and risks were not adequately remediated

- To its credit, CRA did conduct relevant external penetration testing on its Authentication Management System/Credential Management System, including penetration testing focused on CRA’s My Account portal in January 2018. However, because this occurred more than two years prior to the attack, it did not catch the misconfiguration exploited by the attackers to bypass security questions - that had been introduced 20 months before the attack. Similarly, it also missed a second misconfiguration, identified by CRA based on attacker activity during the attack, that could be exploited to bypass the password verification stage and access accounts requiring only a username and a correct answer to one security question.Footnote 24

- In addition, the penetration testing in January 2018 identified, as a high-risk vulnerability, a weakness in CRA’s account recovery authentication process described earlier in this report (paragraph 52).Footnote 25 This weakness had not been remediated by the time of the breach, more than two years later.

- Given the evolution of risk-threats, and the speed at which vulnerabilities can be exploited, high risk vulnerabilities in a system protecting such a high volume of sensitive personal information should be remediated quickly, within a matter of days, not years.Footnote 26

- CRA also conducted internal security assessments of its systems, including one in June 2019 and another in March 2020. However, it conducted no independent external assessments, and based on reports provided to OPC, the assessments were limited and did not provide adequate assurance of the effectiveness of safeguards. In fact, neither of the security assessments detected the misconfigurations introduced in November 2018.

- On shifting safeguard responsibility, similar to ESDC, CRA indicated that with respect to ESDC’s safeguards (and in turn SSC’s) which it was using via the e-link, at the time of the breach it relied on assurances from ESDC on their adequacy, accompanied by review of certain ESDC assessments, such as ESDC’s assessments of the e-link itself.

A coordinated and collaborative approach is needed to assessing adequacy of shared safeguards

- Privacy is a shared responsibility, and ultimately, each department is accountable for ensuring the protection of personal information under its control. In considering the submissions of different departments on the adequacy of measures taken, or not taken, a theme emerged that responsibilities for assessing adequacy often rested with someone else. Clearly, if every department were to take the position that another department was responsible, then an accountability deficit would ensue.

- Based on the above deficits, we find that neither ESDC nor CRA took all reasonable steps, with respect to informed and accountable security decision-making, to: (i) ensure the accuracy of personal information used for administrative purposes as required by subsection 6(2) of the Act, or (ii) prevent the disclosures that contravened section 8 of the Act.

Recommendations C and D - Informed and accountable security decision-making

- We made two related recommendations which CRA and ESDC both accepted and which SSC and TBS agreed they would collaborate to support. Specifically, we recommended that:

- within 12 months, CRA and ESDC, in collaboration with SSC, TBS, and any other relevant partners and subcontractors, develop clear processes to ensure that they are comprehensively and quickly informed of evolving threats and vulnerabilities that affect safeguards they rely on, as well as the state of those safeguards themselves, to inform their decision-making.

- both CRA and ESDC: (i) conduct at least annually, an internal assessment of the security of their online services, and at least every two years, an external security assessment, and (ii) conduct regular internal and external penetration testing, including external testing at least annually. These assessments and penetration tests should be comprehensive, covering all safeguards (not just those under their direct control) and be informed by adequate information about all parts of their online service delivery systems.

- CRA accepted recommendation (c), indicating that it believed it has already fulfilled the recommendation via the revisions made by TBS to the GC CSEMP and that details are included in a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with ESDC. ESDC also accepted recommendation (c). Specifically, it committed to review all existing processes related to the speed and timing of: (i) the reporting of evolving threats and vulnerabilities, and (ii) the assessment of the state of current safeguards. As well, it committed to establishing a separate protocol with the partners identified in this recommendation to ensure that the roles and responsibilities of all parties are well documented and understood.

- ESDC accepted recommendation (d) indicating that it would leverage SSC or other external vendors if necessary, though it noted that it would conduct annual internal vulnerability assessments and biannual external vulnerability assessments contingent on funding availability.

- CRA also accepted recommendation (d), though it stated that in its view both the recommendation for periodic external vulnerability assessments and the recommended frequency of vulnerability assessments “does not follow CCCS Guidelines or TBS policies on security testing.” It also noted that penetration testing is not recommended as a baseline security control for systems protecting information whose compromise could cause medium/moderate harm in either the CCCS’s ITSG-33 IT security risk management: A lifecycle approach or the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (“NIST”) 800-53 Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (an internationally accepted standard with respect to IT security controls).

- With respect to vulnerability assessments, while CCCS’ ITSG-33 does not expressly recommend independent external assessments (or a specific frequency of assessments), our expectation outlined above is consistent with internationally recognized standards, including NIST 800-53, which recommends that security controls for systems protecting information where unauthorized disclosure or modification could cause moderate impactFootnote 27 should include periodic independent security assessments. Based on accepted norms, the frequency of such assessments should be at least annually for internal and biannually for external.

- With respect to penetration testing, while NIST 800-53 and the CCCS’s ITSG-33 do not expressly recommend penetration testing as a baseline safeguard for information whose compromise could cause medium/moderate risk, both say that suggested security controls are a starting point and need to be tailored to meet the specific business, technical and threat contexts. As noted in OPC’s investigation of the security safeguards of the World Anti-Doping Association, published in 2019, organizations must ensure that in designing their safeguards they consider the degree to which the organization’s platform presents a high-value target for attacks.Footnote 28 In our view, the volume, elevated sensitivity and attractiveness of the ESDC and CRA’s personal information holdings, combined with the high degree of internet-facing accessibility of that information, made it clear that comprehensive penetration testing was warranted annually for both departments’ online services.

- CRA also noted the challenges of imposing requirements on partners and sub-contractors. However, CRA is ultimately accountable for the personal information under its stewardship, and ensuring adequacy of safeguards is part of its obligations under the Privacy Act. It is critical that such controls be built into MOUs and contracts where a department relies on systems provided by a third party.

- Given than both ESC and CRA accepted the recommendations, we find the disclosure and accuracy matters, as they relate to informed and accountable security decision-making, to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

- To remedy any ambiguity, we also encouraged CCCS and TBS to clarify the expectations for departments protecting sensitive personal information accessible via internet-facing portals (where categorized as ‘medium’ impact should compromise occur). We would encourage that such clarifications address: (i) penetration testing, (ii) external versus internal security assessments, and (iii) security controls for use of third-party systems. TBS confirmed that it would work with CCCS to do so.

Deficiency 3: Lack of effective monitoring to detect and promptly contain the ongoing breach

- CCCS User authentication guidance for information technology systems (ITSP.30.031 v3), states that for all levels of assurance, authentication systems should be monitored to detect unusual patterns of authentication failures. This would enable swift follow-up on red flag activities to address any compromise from password attacks.Footnote 29 Active monitoring is a critical protective measure that can catch a potential or actual attack at the earliest stages, enabling rapid response and containment.

Monitoring was in place for ESDC portal (via 2Keys), but not for CRA portal

- Despite the above, CRA was not conducting active monitoring of authentications via its portal for suspicious activity, and therefore did not detect the attack until it received a tip from law enforcement on August 7, 2020. This was nearly two weeks after the commencement of bot logins which CRA indicated began July 26, 2020. 2Keys was conducting monitoring of GCKey logins used by the ESDC portal. This led it to detect anomalies in authentication requests via GCKey on July 26, 2020, three days after the approximate start date and 10 days before the peak of the attack on August 5, 2020.

For GCKey breach, communications to accountable decision-makers were delayed and incomplete

- However, monitoring is only effective if red flags are heeded and accountable decision-makers are given adequate information to make timely and informed decisions. 2Keys only alerted SSC to the attack on GCKey on August 4, 2020, after monitoring and conducting an internal investigation. This was more than a week after indicators of the attack were first detected by 2Keys. ESDC, despite being ultimately accountable for all the ESDC information accessible via the GCKey login service, was not informed by SSC until August 5, 2020. Similarly, CRA, accountable for all the CRA information accessible via the GCKey login service (via the e-link between CRA and ESDC) was not informed of the GCKey breach by ESDC until August 7, 2020. Further, according to internal correspondence, ESDC, and through it CRA, initially understood that the attack began August 5, 2020 (not July 23, 2020), was under control and had been contained as of August 7, 2020.

Monitoring was ineffective as resulting action to contain the breach was slow

- The monitoring of authentications is only effective if followed by prompt corrective action to either: (i) prevent an imminent attack, or (ii) effectively cut-off an ongoing attack from accessing and modifying further personal information.

- CRA Portal: After detecting the attack on its portal, CRA took a range of countermeasures including stemming the attack temporarily on August 11, 2020, by completing a fix for a misconfiguration in its systems that had allowed attackers to bypass a requirement to answer a security question (on top of username and password) when logging-in from a new device. However, CRA did not shut down its portal until August 15, 2020, after it detected renewed successful credential stuffing (of usernames, passwords and security question answers) and subsequently implemented a CAPTCHA.Footnote 30 Given that CRA was aware the attack was large scale and ongoing, with sensitive personal information being disclosed to attackers from August 7th to 11th, in our view CRA should have acted more quickly to shut down its portal while it developed solutions.

- Similarly, ESDC and CRA did not shut the e-link to prevent the attackers reaching CRA accounts via the ESDC portal (and vice versa) until a week after they first communicated with each other about the breaches.

- ESDC Portal: After first detecting anomalies on July 26th, 2020, 2Keys began implementing countermeasures, under the direction of SSC, a week and a half later on August 5, 2020. Certain measures temporarily impeded the attack before the attackers adapted, using commonly available infiltrative techniques. It took nearly three weeks for 2Keys, under SSC direction and in collaboration with implicated federal institutions, to add a CAPTCHA to GCKey – after which no new successful credential stuffing via the ESDC portal was detected. ESDC did not shut down its portal during this period, but only did so as a precautionary measure on August 20, 2020, two weeks after learning of the breach. Due to these delays ESDC therefore missed the opportunity to prevent the majority of the unauthorized disclosures and modifications via its portal which occurred in the weeks after July 26, 2020.

- 2Keys asserted that implementing CAPTCHA controls on the GCKey service in less than three weeks was an incredible technical achievement, and SSC indicated that “timeliness was within global standards.” Unfortunately, such a timeline to contain an active breach does not provide the protection warranted for sensitive personal information.

- This reinforces that an effective monitoring regime must include preparedness to take swift corrective action in response to a threat. Such preparedness would include strong coordination and communication channels being in place, having safeguards enhancements (like CAPTCHA and MFA) ready to deploy, and having portal shut-down protocols. In our view, corrective measures (or ESDC portal shutdown while corrective measures were developed) should have been implemented more quickly to contain the breach, considering the scale and ongoing nature of the attack and the sensitivity of the personal information being disclosed to, and modified by, attackers.

- In summary, while ESDC had monitoring in place (via 2Keys), and both CRA and ESDC (in partnership with SSC and 2Keys) coordinated and took containment measures once detecting the breach, we find that neither had an effective monitoring regime in place to detect and promptly contain authentication-related breaches. These measures therefore did not constitute “all reasonable steps” to meet the accuracy requirements of subsection 6(2) and to prevent the disclosures that contravened section 8.

Recommendations E and F – Monitoring

- SSC indicated that after the breach it has, with 2Keys, implemented improved cyber event management processes to mitigate reoccurrences. CRA has also since implemented monitoring of logins for suspicious patterns. To ensure that CRA and ESDC’s monitoring is effective, we recommended that:

- within 6 months, both CRA and ESDC demonstrate to OPC that they have plans in place, supported by effective communications and decision-making frameworks, to permit them to respond quickly to attacks detected through active monitoring of logins to their online services; and

- within 12 months, CRA and ESDC, in collaboration with SSC, TBS, and any other relevant partners and subcontractors, develop clear processes to ensure that they are comprehensively and quickly informed of all material breaches affecting personal information under their control, with fulsome details of active breaches to inform decision-making on breach response and containment in a timely way.

- For clarity, the plans referenced in recommendation (e) should include addressing key types of attacks that could occur (based on environmental scanning of the threat environment), as well as protocols for implementing broad measures, such as portal shutdowns where warranted, in the case of novel attacks.

- ESDC accepted the recommendations and committed to collaborating with CRA to improve and update plans to respond quickly to attacks detected through active monitoring of logins via online services, as well as to establishing a separate protocol with the partners identified in this recommendation to ensure that the roles and responsibilities of all parties are well documented and understood.

- CRA noted that it now has an MOU with ESDC to share cyber-related indicators of compromise and accepted the recommendations. TBS and SSC both committed to supporting CRA and ESDC’s efforts.

- Therefore, we find the disclosure and accuracy matters, as they relate to effective monitoring, to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

Other federal departments using the GCKey Service for authentication

- At the time of the breach, the GCKey Service had been used by approximately 30 federal departments to authenticate individuals before they can access certain online services or applications. In addition to ESDC and CRA, we investigated 23 departments using GCKey at the time of the attack.Footnote 31

- The other departments all confirmed to OPC that they reviewed their systems for any indications of logins to their services during the attack window by GCKey credentials identified as compromised. None of the departments found indicators of fraudulent access or modification of personal information, corroborating the apparent focus on the attacks on ESDC and CRA services. Except in two cases, the departments were able to confirm that any successful logins to their services had either passed additional authentication measures or had been validated with the users after the fact as being legitimate.

- Specifically, Health Canada (“HC”) was unable to confirm the authenticity of two logins to its Cannabis Tracking and Licensing System, and Transport Canada (“TC”) was unable to confirm authenticity of five logins to its General Aviation Licensing On-line application, and neither department had any additional security measures in place. HC and TC both reported the matter to OPC as a privacy breach on the basis that they could not rule out unauthorized disclosures under section 8 of the Act. Given that the compromised credentials in question were revoked with respect to HC and TC we find the matter well-founded and resolved, and with respect to the other departments we find the matter not well-founded. Nonetheless, we encourage all departments employing the GCKey Service to carefully review this report of findings and apply the lessons learned as relevant.

Conclusion

- In sum, while both CRA and ESDC, in partnership with SSC and 2Keys, had certain measures in place to safeguard against unauthorized disclosure and modification via credential stuffing and identity theft attacks, for the reasons described in this report, these measures did not constitute adequate steps to prevent the compromise of the sensitive personal information of tens of thousands of Canadians.

- ESDC and CRA both under-assessed the level of identity authentication warranted given the elevated value and sensitivity of the personal information accessible online via their platforms. In this context they did not implement sufficient safeguards, including adequate verification of identity for new accounts and MFA for existing accounts. While single factor authentication may have been common practice at the time, common practice does not necessarily equate to compliant practice.

- Further, both departments had inadequately informed and accountable security decision-making due to a siloed approach to interdepartmental accountability and information sharing as well as inadequate assessments and testing of security. Finally, both departments lacked sufficient monitoring, supported by effective interdepartmental coordination, to detect and promptly contain the ongoing breach.

- Accordingly, we find that CRA and ESDC both contravened the accuracy provisions of subsection 6(2) and that neither CRA nor ESDC took adequate measures to prevent the unauthorized disclosures made in contravention of section 8.

- We made a range of related recommendations in our analysis above, which are consolidated below for ease of reference:

- within 6 months, ESDC and CRA alter their identity assurance practices, for all of their online services, to adopt practices, aligned with internationally accepted standardsFootnote 32 for identity assurance in cases where moderate harm could result.

- within 12 months, ESDC adopt account recovery authentication measures that rely on MFA for all its online services that enable access to, or modification of, personal information.

- within 12 months, CRA and ESDC, in collaboration with SSC, TBS, and any other relevant partners and subcontractors, develop clear processes to ensure that they are comprehensively and quickly informed of evolving threats and vulnerabilities that affect safeguards they rely on, as well as the state of those safeguards themselves, to inform their decision-making.

- both CRA and ESDC: (i) conduct at least annually, an internal assessment of the security of their online services, and at least every two years, an external security assessment, and (ii) conduct regular internal and external penetration testing, including external testing at least annually. These assessments and penetration tests should be comprehensive, covering all safeguards (not just those under their direct control) and be informed by adequate information about all parts of their online service delivery systems.

- within 6 months, both CRA and ESDC demonstrate to OPC that they have plans in place, supported by effective communications and decision-making frameworks, to permit them to respond quickly to attacks detected through active monitoring of logins to their online services.

- within 12 months, CRA and ESDC, in collaboration with SSC, TBS, and any other relevant partners and subcontractors, develop clear processes to ensure that they are comprehensively and quickly informed of all material breaches affecting personal information under their control, with fulsome details of active breaches to inform decision-making on breach response and containment in a timely way.

- CRA accepted all the recommendations. ESDC similarly accepted all the recommendations, though in one case contingent on the availability of funding. We expect ESDC to take the steps necessary to ensure that cyber security to protect the privacy of Canadians is appropriately resourced and to robustly implement all the recommendations.

- The report notes the challenges that OPC faced in fulfilling our mandate with respect to protecting the privacy of Canadians – both in terms of delayed and missing breach reports and accessing information from departments during the investigation. Unnecessary delays can increase harms flowing from a breach and hinder the investigative process. We stress the importance of fulsome cooperation with investigations to the benefit of both organizations and Canadians. In addition, we are following up with CRA on separate breaches regarding CERB fraud in 2020 that we learned about in the final stages of this investigation which preliminary information indicates could have affected up to 15,000 individuals. OPC’s ability to fulfill its mandate and provide timely advice and recommendations to protect the privacy rights of Canadians affected by a privacy breach depends on departments fulfilling their obligations to provide meaningful and timely information, and we remind departments of their obligation to report material privacy breaches to OPC within seven days under the TBS Policy on Privacy Protection.

- Notwithstanding the above-noted challenges, we appreciate and are encouraged by the commitment by both CRA and ESDC to implement the recommendations in the report towards enhancing the privacy protection of Canadians’ personal information on the GCKey and related platforms.

- The CRA and GCKey breaches represented a sophisticated and coordinated attack, impacting departments across the Government of Canada and their partners. This breach resulted in the compromise of tens of thousands of Canadians’ sensitive personal information, resulting in harms from identity theft, financial hardship and psychological stress. This report highlights numerous opportunities to improve the Government of Canada security safeguard systems, in particular where partners rely on each other and share accountability. We will expect all government departments to consider the lessons from this report in reducing the probability of a future breach of this magnitude.

Annex A

Appendix B of the GC Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements in place now and at the time of the incidents, provides examples of harms that are suitable to be considered level 2 versus level 3. Excerpts of relevant categories of harm applicable to this context are replicated below:

| Category of Harm | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial loss | No financial loss | Financial loss that has no impact or only an insignificant material impact on the financial standing of an individual or organization A budgetary impact that may require reallocation of funds but no additional financing |

Loss of a financial amount that has a significant material impact on the financial standing of an individual or organization A budgetary impact that may require re-allocation of funds and additional financing |

Loss of a financial amount that severely jeopardizes the financial standing of an individual or organization Financial restructuring may be required |

| Unauthorized release of sensitive personal or commercial information | No loss of privacy No increase in public scrutiny or media attention |

Loss of privacy, unwanted surveillance, tracking, monitoring, data profiling or data matching [business related content] |

Potential inability to fulfill legal or contractual obligations [business related content] |

Disruption of social order or civil unrest [business related content] Loss of authority (e.g., due to intervention [of] external party) |

| Personal health and safety | (Any compromise [of] health and safety is assessed at minimum of Level 2) | No physical injury or psychological distress that requires treatment by first-aid personnel or health care professional | A physical injury or psychological distress that requires treatment by first-aid personnel or health care professional | A physical injury or psychological distress that requires an emergency response |

- Date modified: