Privacy in a pandemic

2019-2020 Annual Report to Parliament on the Privacy Act and Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

© Her Majesty the Queen of Canada for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2020

ISSN 1913-3367

Commissioner’s message

The need for federal privacy laws better suited to protecting Canadians in the digital age has been a common thread in our annual reports to Parliament for many years.

Last year in this space, I noted how major investigations into Statistics Canada, Facebook and Equifax had all revealed serious weaknesses within the current legislation.

This year, the COVID-19 pandemic makes the significant gaps in our legislative framework all the more striking.

The pandemic has raised numerous issues for the protection of personal information. Around the world, there have been heated debates about contact tracing applications and their impact on privacy. Many of us have been asked to submit to health monitoring measures at the airport, or before we enter workspaces, restaurants and stores.

More broadly, the pandemic has accelerated the digital revolution – bringing both benefits as well as risks for privacy.

The need for social distancing has meant that even more of daily life takes place via the use of technology. Instead of meeting in person, we have further shifted to working, socializing, going to school and seeing the doctor remotely, through videoconferencing services and online platforms.

Technologies have been very useful in halting the spread of COVID-19 by allowing essential activities to continue safely. They can and do serve the public good.

At the same time, however, they raise new privacy risks. For example, telemedicine creates risks to doctor-patient confidentiality when virtual platforms involve commercial enterprises. E-learning platforms can capture sensitive information about students’ learning disabilities and other behavioural issues.

As the pandemic speeds up digitization, basic privacy principles that would allow us to use public health measures without jeopardizing our rights are, in some cases, best practices rather than requirements under the existing legal framework.

We see, for instance, that the law has not properly contemplated privacy protection in the context of public-private partnerships, nor does it mandate app developers to consider Privacy by Design, or the principles of necessity and proportionality.

The law is simply not up to protecting our rights in a digital environment. Risks to privacy and other rights are heightened by the fact that the pandemic is fueling rapid societal and economic transformation in a context where our laws fail to provide Canadians with effective protection.

In our previous annual report, we shared our vision of how best to protect the privacy rights of Canadians and called on parliamentarians to adopt rights-based privacy laws.

We noted that privacy is a fundamental human right (the freedom to live and develop free from surveillance). It is also a precondition for exercising other human rights, such as equality rights in an age when machines and algorithms make decisions about us, and democratic rights when technologies can thwart democratic processes.

Regulating privacy is essential not only to support electronic commerce and digital services; it is a matter of justice.

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in Canada, some felt privacy should be set aside because protecting the lives of Canadians was more important. Given the gravity and the immediacy of the situation, that reaction was not surprising. However, it was based on a false assumption: either we protect public health, or we protect privacy.

When I appeared before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology in May 2020, I indicated that, when properly designed, tracing applications could achieve both public health objectives and the protection of rights simultaneously.

Technology itself is neither good nor bad. Everything depends on how it is designed, used and regulated.

Technology can be used to protect both public health and privacy. I firmly believe that privacy and innovation brought about by new technology are not conflicting values and can coexist. We have seen some good design choices in developing certain public health measures – notably with respect to the federal government’s COVID Alert application.

That being said, the fact remains that our existing legislative framework for privacy is outdated and does not sufficiently deal with the digital environment to ensure appropriate regulation of new technologies.

A recovery based on innovation will only be sustainable if it adequately protects the interests and rights of all citizens. These can, and should, be reflected in our laws.

We need a legal framework that will allow technologies to produce benefits in the public interest while also preserving our fundamental right to privacy. This is an opportune moment to demonstrate to Canadians that they can have both.

OPC response to the pandemic

Throughout the pandemic, my office has recognized that the current health crisis calls for a flexible and contextual application of privacy laws. However, because privacy is a fundamental right, it is very important in our democratic country based on the rule of law that key principles continue to operate, even if some of the more detailed requirements are not applied as strictly as they normally would be.

With a view to achieving both greater flexibility and ensuring respect for privacy as a fundamental right, in April we released a framework to assess privacy-impactful initiatives in response to the pandemic.

We also published guidance to help organizations subject to federal privacy laws understand their privacy-related obligations during the pandemic.

In May, we issued a joint statement with our provincial and territorial counterparts, outlining key privacy principles to consider as contact tracing and similar digital applications are developed.

Privacy guardians from across the country felt it was important to issue a common statement because these applications raise important privacy risks.

But the fact that such a statement was necessary is an unfortunate reminder that some of Canada’s privacy laws – certainly its federal laws – do not provide a level of protection suited to the digital environment.

Respect for privacy rights should not be a suggested best practice left to the goodwill of government officials or big tech. It should be a clearly codified and enforceable requirement.

In a joint resolution last fall, our provincial and territorial counterparts also joined us in calling for effective privacy legislation in a data driven society.

Our response to the pandemic as well as how this enormous public health challenge demonstrates the importance of rights-based law reform is described in more detail in the next section of this annual report, Privacy in a pandemic.

Further reading

- Privacy and the COVID-19 outbreak: Guidance on applicable federal privacy laws, March 2020

- A framework for the government of Canada to assess privacy-impactful initiatives in response to COVID-19, April 2020

- Effective privacy and access to information legislation in a data driven society: Resolution of the federal, provincial and territorial information and privacy commissioners, October 2019

Conclusion

Incorporating good privacy design into COVID-related initiatives will help to build public trust in public health measures, in government and in the digital tools that have become so important to day-to-day life.

The choices our government makes about protecting public health and fundamental values such as the right to privacy will have long-term impacts for all Canadians.

Similarly, the path that the government ultimately chooses to take when it comes to legislative reform will have a significant effect on future generations.

You will read in later chapters of this report about other work done by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) during the past year. You will learn of a variety of investigations, of our success in reducing the number of older investigation files, and of the advice we provided to government and businesses to ensure privacy and public health are protected simultaneously. These activities continued as we were faced with unprecedented operational challenges.

On a closing note, as I look back at the past year, I feel fortunate to have talented, dedicated people working alongside me. When the pandemic emerged, the team supported public and private sector organizations. They answered questions from the public and the media on privacy and the pandemic, and helped me respond to requests from parliamentarians related to the health crisis – all while still taking complaints, reviewing breach reports, investigating potential violations of the law, and keeping our IT system running smoothly so as to be able to offer services to Canadians.

They have accomplished all this as they themselves were transitioning to telework and rearranging their lives to comply with public health guidelines. Canadians are very fortunate to have people with such passion and knowledge working to protect their privacy at all times.

Privacy by the numbers

| Privacy Act complaints accepted | 761 |

|---|---|

| Privacy Act complaints closed through early resolution | 338 |

| Privacy Act complaints closed through standard investigation | 997 |

| Well-founded complaints under the Privacy Act | 82% |

| Data breach reports received under the Privacy Act | 341 |

| Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) received | 78 |

| Advisory consultations with government departments | 66 |

| Advice provided to public-sector organizations following PIA review or consultation | 121 |

| Public interest disclosures by federal organizations | 611 |

| PIPEDA complaints accepted | 289 |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through early resolution | 221 |

| PIPEDA complaints closed through standard investigation | 97 |

| Well-founded complaints under PIPEDA | 78% |

| Data breach reports received under PIPEDA | 678 |

| Advisory engagements with private-sector organizations | 19 |

| Bills, legislation and parliamentary studies reviewed for privacy implication | 29 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on private- and public-sector matters | 8 |

| Information requests | 11,450 |

| Speeches and presentations | 74 |

| Visits to website | 2,813,127 |

| Blog visits | 95,190 |

| Tweets sent | 1,054 |

| Twitter followers | 17,092 |

| Publications distributed | 43,746 |

| News releases and announcements | 50 |

Privacy in a pandemic

Emergency response highlights the importance of protecting rights and ensuring trust

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused tragedy and disruption world-wide. Efforts to contain the virus and cope with its social and economic fallout have prompted abrupt and colossal change.

Technology is playing a central role as the world looks to halt the spread of COVID-19 and adapt regular activities to the need for social distancing. Public health and government officials have turned to digital tools such as contact tracing applications as part of the answer to combatting the deadly virus.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has dramatically accelerated the already rapid adoption of disruptive technologies into our day-to-day lives. More of our interactions take place online – be it for socializing with friends and family, doing business or going to school. By necessity, telework, e-learning, and telemedicine are suddenly far more prevalent.

Videoconferencing and other online services have been helpful in allowing some semblance of normal life to continue in the wake of the pandemic. At the same time, however, they are creating important new risks to our privacy rights.

This is particularly concerning given our current privacy laws do not provide an effective level of protection suited to the digital environment.

In our previous annual report, we urged Parliament to adopt rights-based privacy laws that would better protect Canadians in the face of data-driven technologies.

We noted once again that dated federal privacy laws designed for different times hamper our work and are no longer up to the task of ensuring respect for the privacy rights of Canadians.

With the pandemic accelerating the digitization of just about every aspect of our lives, the future we have long been urging the government to prepare for has arrived in a sudden, dramatic fashion. This rapid societal transformation is taking place without the proper legislative framework to guide decisions and protect fundamental rights.

While we look forward to more in-person activities once the threat of the pandemic eases, the so-called “new normal” will likely include more digital interactions and more unwanted – and often undetectable – intrusions into our privacy.

We are collectively encountering uncertain and extraordinary circumstances during the pandemic. These circumstances reveal just how important it is to have laws anchored on a human rights foundation to guide decision-making. Entrenching privacy in its proper human rights context remains not just relevant, but more necessary than ever.

This chapter addresses how the pandemic reinforces the need for laws that protect rights and reflect fundamental Canadian values. It also discusses our office’s approach to privacy issues raised by the pandemic. This includes our work with government institutions and commercial organizations to ensure important privacy principles are integrated in the design of COVID-19-related initiatives.

Finally, it provides an update on developments related to law reform since we published our blueprint for legislative modernization in our previous annual report.

Further reading

- Privacy law reform: A pathway to respecting rights and restoring trust in government in the digital economy, December 2019

- A Data Privacy Day Conversation with Canada’s Privacy Commissioner: Address by Daniel Therrien at the University of Ottawa Law School, January 2020

- Global privacy expectations of video teleconference providers: Open letter, July 2020

Response to the fallout of COVID-19

Throughout the pandemic, our office has recognized that the current health crisis calls for a flexible and contextual application of privacy laws. However, because privacy is a fundamental right, it is very important in our democratic country based on the rule of law that key principles continue to operate, even if some of the more detailed requirements are not applied as strictly as they normally would be.

With a view to achieving both greater flexibility and ensuring respect for privacy as a fundamental right, in April the OPC released a framework to assess privacy-impactful initiatives in response to the pandemic.

Following this, in May we issued a joint statement with provincial and territorial privacy commissioners on privacy principles that should be respected in the design and during the use of any contact tracing or similar application.

Both these documents were meant to offer clear guidance on how to incorporate privacy into the design of government programs to address the pandemic, in recognition of the fact that our laws do not provide an effective level of protection suited to the digital environment.

Some of the principles put forth in our guidance documents are not legal requirements in our current privacy laws, yet are considered internationally to be fundamental privacy protective measures.

The framework sets out the most relevant privacy principles in the context of the pandemic, without abandoning others. Some of the key principles we noted were:

- legal authority: the proposed measures must have a clear legal basis;

- measures must be necessary and proportionate, and therefore be science-based and necessary to achieve a specific identified purpose;

- purpose limitation: personal information must be used to protect public health and for no other purpose;

- use de-identified or aggregate data whenever possible;

- exceptional measures should be time-limited and data collected during this period should be destroyed when the crisis ends; and

- transparency and accountability: government should be clear about the basis and the terms applicable to exceptional measures, and be accountable for them.

Similar to the OPC framework, the joint statement called on governments looking to adopt tracing applications to respect a number of key principles. For example, we said that the use of apps must be voluntary and that their use must be necessary and proportionate, which requires evidence of their likely effectiveness.

Further reading

- Privacy and the COVID-19 outbreak, March 2020

- A framework for the government of Canada to assess privacy-impactful initiatives in response to COVID-19, April 2020

- Joint statement by Federal, Provincial and Territorial Privacy Commissioners, Supporting public health, building public trust: Privacy principles for contact tracing and similar apps, May 2020

Advisory work on COVID-19 initiatives

During the pandemic, a number of government and non-government organizations consulted our office on various initiatives related to the pandemic.

These initiatives included a contact tracing app developed by a non-governmental organization, the federal government’s COVID Alert application, as well as a retailer’s proposal to introduce temperature checks at the front door of its stores.

In the weeks preceding the launch of the COVID Alert exposure notification app, our office and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (IPC) engaged in productive and in-depth discussions with the federal and Ontario governments.

We provided recommendations to our respective governments based on the key privacy principles outlined in our joint federal, provincial and territorial statement on tracing applications. Because the app was being positioned as a national initiative, our office and the IPC also consulted other provincial and territorial privacy commissioners.

Our office and the IPC supported the use of the COVID Alert app by individuals based in part on an understanding that using the app would be voluntary. However, while the use of the app may be voluntary as it relates to the federal and Ontario governments, there is still a risk that third parties may seek to compel app users to disclose information as to their use of the app, including any exposure notifications.

We also supported the use of the COVID Alert app on the basis that it be effective. The governments sufficiently demonstrated that the application, although new and untested, was likely to be effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19, as part of a broader set of measures that includes manual contact tracing. However, because the effectiveness was uncertain, we recommended that the implementation of the app be closely monitored and that the app be decommissioned if new evidence indicated it was not effective in achieving its intended purpose.

Independent oversight will be important to foster public trust. The federal government agreed to involve our office in an audit of the app after it is up and running. The audit will include ongoing analysis of the necessity and proportionality of the app, including its effectiveness, and an assessment of respect for the federal, provincial and territorial joint statement principles in the design and implementation of the app.

In addition to the work on the COVID Alert application, we were consulted by a number of public sector institutions on initiatives developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This work is ongoing at the time of writing.

This has included providing advice on new activities including those related to social benefit programs, the federal government’s COVID-19 mandatory isolation order for people entering Canada, and temperature screening of passengers on flights in and out of Canada.

One of the social benefit programs we examined in our work was one-time $600 payment in recognition of the extraordinary expenses faced by persons with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the initiative is jointly administered by the Canada Revenue Agency, Veterans Affairs Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada, we suggested that the letters of agreement between the departments include clear provisions on purpose limitations and retention.

In reviewing measures to support the mandatory isolation order, which requires individuals entering Canada to isolate for 14 days, we recommended that institutions retain personal information only for as long as is necessary. We also recommended institutions limit the use of personal information to the purpose for which it was collected, namely public health follow-up and compliance verification.

At the time of writing we had yet to complete our review of the temperature screening program in Canadian airports. However, we had provided recommendations to the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) on transparency and on the collection, use, disclosure and retention of personal information.

We also advised Transport Canada and CATSA to keep informed of public health guidance that may be released on temperature screening, and to consider this guidance when assessing the effectiveness of the initiative.

On the private-sector side, a national retailer contacted our office to seek advice as it was considering screening the temperature of customers entering its stores to help mitigate against the risk of the spread of COVID-19. In particular, the organization indicated that an end result of the temperature screening program it was contemplating included requiring individuals to wear masks in their stores.

We were encouraged to see that the retailer’s considerations included a number of key privacy protective measures, such as obtaining express consent from customers before performing a temperature check, and not recording or retaining any personal information obtained through thermal cameras.

We recommended the organization consider the impact of new requirements to wear masks or other face coverings on its stated needs for the program and, overall, whether it could achieve its goals through less privacy invasive means. We provided a number of recommendations to the retailer should they decide to proceed with temperature screening, including that they only use the thermal cameras in “live feed” mode so as to not retain any personal information, ensure they obtain meaningful consent from customers, and that the program be regularly re-evaluated to ensure alignment with any new guidance released by relevant public health authorities.

COVID-19 and law reform objectives

The pandemic has accelerated the digitization of our lives, moving more of our activities online in an effort to remain safe.

While technology offers tremendous benefits, it also raises risks that are not properly mitigated under the current legislative framework.

We have welcomed efforts by certain organizations in both the private and public sectors to design their initiatives in a privacy protective way.

The federal government’s COVID Alert application is a case in point. When the government first consulted us, the design of the app was good, but it did not meet all key privacy principles outlined in our framework. After productive discussions, the app ultimately did comply with these principles. This example shows that when government institutions or companies want to adopt Privacy by Design, they can.

However, the positive examples we see don’t take away from the urgent need for law reform. While some try to take the right steps to protect privacy, others do not.

Even in the largely positive story of the COVID Alert app, discussions with the federal government highlighted broader concerns related to law reform.

Despite the fact that such applications are extremely privacy sensitive and the subject of global concern for the future of democratic values, the government asserted that the federal Privacy Act does not apply to the initiative, based on its view that the COVID Alert does not collect personal information.

And while the app is voluntary as it relates to the government, there is still a possibility that third parties may seek to compel app users to disclose information as to their use of the app, including any exposure notifications. The governments undertook to communicate publicly that individuals should not be required to use the app or to disclose information about their use of the app.

This step will mitigate, but not eliminate, the risk to the voluntary nature of the app. Other countries have legislated to ensure similar apps are completely voluntary. This again highlights an issue that should be examined as part of legislative modernization.

Other advisory work during the pandemic highlighted the need to examine issues related to public-private partnerships.

We noted that several COVID-19 related initiatives involved the collection of personal information by commercial entities, whether through public-private partnerships or other forms of reliance on the private sector.

We saw an instance where agreements related to a product allowed a company to use personal information beyond the purposes specified for its collection. These agreements, where the terms were difficult for individuals to understand, were used as a basis for consent. Following discussions with the government department, the privacy notice upon which user consent is obtained was improved.

At the outset of the government's response to the pandemic, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) introduced interim measures to relax the privacy impact assessment (PIA) process for initiatives adopted by federal institutions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In our office's review of these measures, we observed that a number of COVID-19-related initiatives involved partnerships with the private sector, but that in cases where the legal authority for an initiative was based on consent obtained by a private-sector organization, there was no policy requirement for government institutions to ensure that this consent was meaningfully obtained.

In response, the TBS asserted that it could not add such a requirement because it was limited to the existing legal framework. According to the TBS, compelling departments to ensure their private-sector partners had obtained meaningful consent would require legislative amendments.

As a result, it remains the case that a public sector institution could deploy a technological solution to the pandemic that allows its private-sector partner to use the personal information collected for commercial purposes unrelated to public health.

This lack of clarity around data collected for a public purpose by a private entity could potentially result in a company releasing an application and using the information for commercial purposes, provided consent is obtained, even if it is done in incomprehensible terms.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have also witnessed an increased use of virtual medicine and e-learning platforms, which has been extremely helpful in allowing education and medical consultations to continue, but comes with new sets of risks.

Access to the doctor’s office has been severely limited in the short term. With virtual medicine, there is a risk of losing doctor-patient confidentiality by virtue of private-sector service providers potentially having access to information from medical visits.

Similarly, many students have been required to use e-learning platforms and videoconferencing during the pandemic, which can result in commercial organizations having access to information related to learning difficulties or other behavioural data of students.

In fact, during the pandemic, we have seen accelerated uses of videoconferencing tools, including for virtual health and learning purposes identified above. Given the sensitive information and vulnerable populations involved, our office joined forces with global counterparts to publish an open letter to video teleconferencing companies reminding them of their obligations to comply with privacy laws and handle people’s personal information responsibly.

We need laws that set explicit limits on permissible uses of data, rather than be left to rely on the good will of companies to act responsibly.

The growing role of public-private partnerships creates additional complexity and risk. At a minimum, we need common privacy principles enshrined in our public- and private-sector laws.

We urgently need rights-based privacy laws that allow technologies to produce benefits in the public interest and ensure privacy rights are protected.

As a former advisor to President Obama recently wrote, no one would think that freedom of assembly is at risk, despite the temporary limitations imposed by the current health crisis. That is because freedom of assembly (in Canada, freedom of association) is constitutionally protected.

There is no such certainty for rights in the digital sphere. Privacy is at risk, and modern laws are required to appropriately protect it as a fundamental right.

Even prior to the pandemic, trends such as increased reliance on technology and on public-private partnerships had reached a tipping point where privacy and democratic rights were strained and reform was overdue.

Our previous annual report discussed how the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, as well as Facebook’s refusal to address privacy deficiencies, spotlighted the need for better protections. That spotlight is now even more intense in the face of the pandemic and its related privacy issues.

As noted previously, our office reviewed interim policy measures introduced by the TBS to provide greater flexibility to federal public sector institutions in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

We expressed concern about these measures, which relaxed existing requirements related to PIAs without offering adequate replacements. Therefore, in our view, the measures did not offer a balanced approach in assessing the impact to privacy of urgent COVID-19-related initiatives.

To address this imbalance, we recommended that the TBS include, in the Interim Directive on Privacy Impact Assessment, a policy statement reminding institutions of the government's commitment to privacy as a fundamental, quasi-constitutional human right, even though the usual rules have been suspended.

In response, the TBS took the position that such a statement would be inconsistent with its legislative and policy framework, going beyond targeted changes to provide flexibility in responding to the pandemic. Despite numerous exchanges, the TBS maintained that it could not do so within the existing legislative framework.

Such reluctance on the part of government to assert privacy as a fundamental right absent such direction from Parliament after debate among elected officials is frankly difficult to understand and is further evidence of the imperative need to reform our legislation.

Further reading

- Joint statement on global privacy expectations of video teleconferencing companies: Open letter, July 2020

- Ghosh, Abecassis and Loveridge, Privacy and the Pandemic: Time for a Digital Bill of Rights, Foreign Policy, April 2020

Blueprint for reform

The recommendations for legislative change set out in our 2018-2019 annual report remain extremely relevant for addressing the new challenges raised by the pandemic. We developed them in the context of a crisis of trust that has been building for years.

Data breaches have affected tens of millions of Canadians. Our public opinion research tells us that some 90% of Canadians are concerned about their inability to protect their privacy. Only 38% believe businesses respect their privacy rights, while just 55% believe government respects their privacy.

There can be no trust if rights are not respected. Good privacy laws are key to promoting trust in both government and private sector organizations. This was true before COVID-19, and it has become even more important in the wake of the pandemic. Canadians want the benefits of digital technologies, and the assurance that they may use those technologies without forgoing their rights.

In our blueprint for legislative reform, we said that the starting point should be to give new privacy laws a rights-based foundation. A central purpose of the law should be to protect privacy as a human right in and of itself and as an essential element to the realization and protection of other rights.

We suggested that both PIPEDA and the Privacy Act include preambles and purpose statements that entrench privacy in its proper human rights framework.

These would serve to bridge the gap between data protection and privacy. They would also provide the values, principles and objectives to guide how the data protection principles in both federal acts are interpreted and applied.

We also advocated for a reformed private-sector privacy law that would no longer be drafted as an industry code of conduct, thus putting an end to self-regulation.

To ensure Canadians can enjoy the benefits of digital technologies safely, we proposed the addition of enforcement mechanisms to offer quick and effective remedies for people whose privacy rights have been violated and to encourage compliance with the law.

These mechanisms would include empowering the Privacy Commissioner to make binding orders and impose consequential administrative penalties for non-compliance with the law, as well as proactive privacy inspections by our office to ensure demonstrable accountability. Such enforcement powers are being used successfully by other data protection authorities around the world.

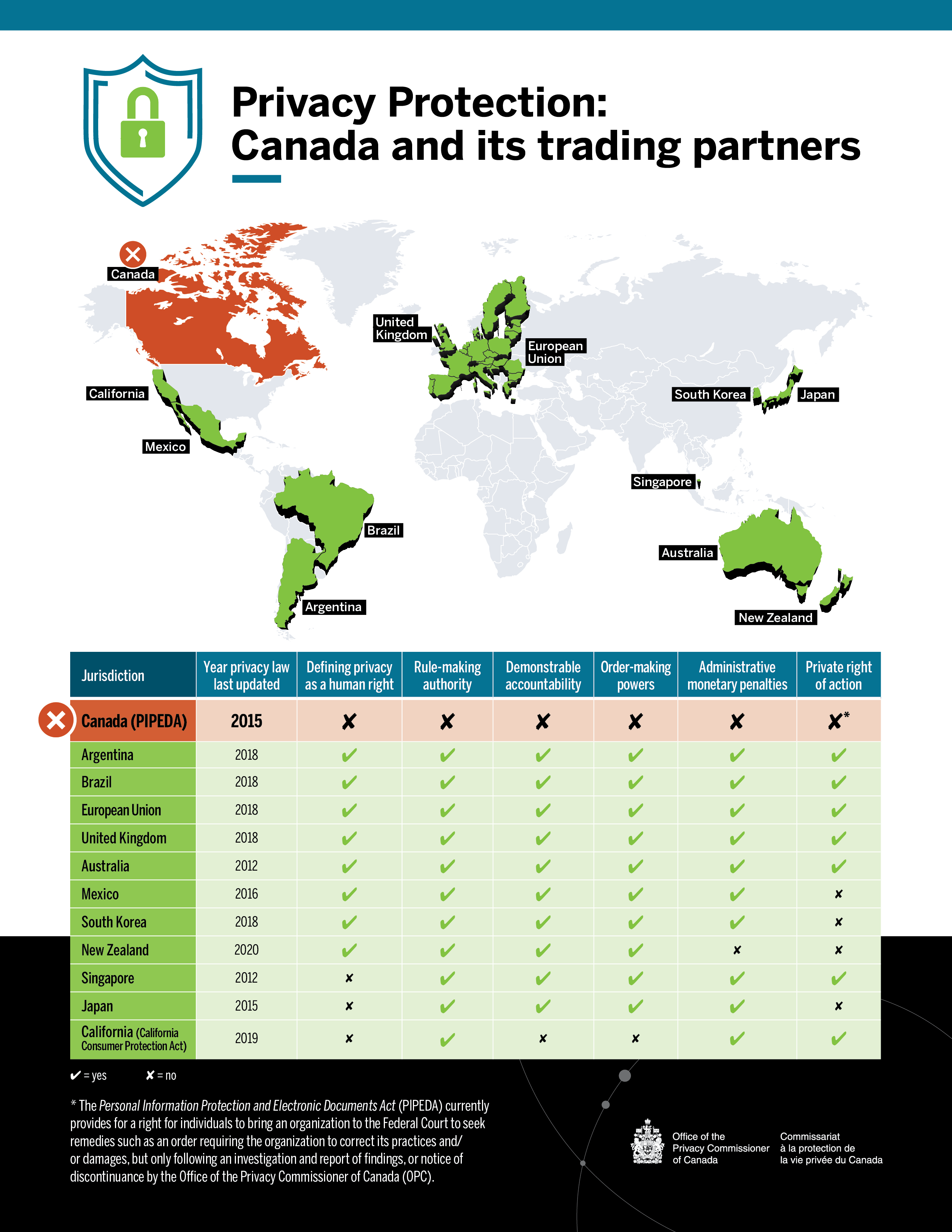

These elements we have called for in our rights-based approach to law reform are in place in the laws of most of Canada’s trading partners, as you can see in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Privacy Protection: Canada and its trading partners

Text version of Figure 1

| Jurisdiction | Year privacy law last updated | Defining privacy as a human right | Rule-making authority | Demonstrable accountability | Order-making powers | Administrative monetary penalties | Private right of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada (PIPEDA) | 2015 | no | no | no | no | no | no* |

| Argentina | 2018 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Brazil | 2018 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| European Union | 2018 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| United Kingdom | 2018 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Australia | 2012 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Mexico | 2016 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| South Korea | 2018 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| New Zealand | 2020 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

| Singapore | 2012 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Japan | 2015 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| California (California Consumer Protection Act) | 2019 | no | yes | yes | no | Yes | yes |

|

* The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) currently provides for a right for individuals to bring an organization to the Federal Court to seek remedies such as an order requiring the organization to correct its practices and/or damages, but only following an investigation and report of findings, or notice of discontinuance by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC). |

|||||||

Defining privacy as a human right: Legislation recognizes privacy as a human right, or adherence to an international agreement that does so (e.g., Convention 108).

Rule-making authority: Data protection authority or other public authority can issue enforceable codes of conduct, standards, guidance and/or regulation.

Demonstrable accountability: Data protection authority can legally seek production of specific records to prove data management practices, prior to investigation, and/or data protection authority has legal authority to conduct proactive inspections, reviews, audits to verify compliance, absent specific grounds to suspect or believe a specific infraction has occurred.

Order-making powers: Data protection authority has the power to back findings with orders for particular remedies.

Private right of action: Legal provisions allowing individuals to directly seek remedies and/or compensation from a court for breaches of privacy laws.

Canada used to be a leader in privacy law, but has clearly fallen behind other jurisdictions in the world.

Our proposals are realistic and contemporary, and they would also improve the interoperability of our laws with other jurisdictions, providing predictability and potentially reducing the cost of compliance for Canadian businesses.

Our proposals also recognize legitimate interests of organizations and government.

We have said that the best way for Canada to position itself as a digital innovation leader is to demonstrate how we can establish a framework for innovation that also successfully protects Canadian values and rights, as well as our democracy. This will also be fundamental to maintaining public trust in both businesses and government.

Update on the road towards reform

We have heard more talk about law reform over this last year than any other time in recent memory.

Back in May 2019, the crisis of trust led the federal government to propose a Digital Charter, which includes plans to update PIPEDA. The government has since reiterated its intent to reform both PIPEDA and the Privacy Act.

However, more than a year later, we have yet to see the specific ways in which our legislative framework would be modernized to live up to the challenges of the digital age – and to Canadians’ expectations.

Shortly after our previous annual report was tabled in Parliament in December 2019, the Prime Minister issued mandate letters to his newly appointed cabinet members. Several of these letters included direction related to privacy law reform.

Various cabinet members were asked to collectively advance a number of legislative and policy elements that could lead to stronger privacy protection for Canadians. Several of these elements referred back to Canada’s Digital Charter.

The proposals for PIPEDA reform under the Digital Charter have some positive elements. For example, it refers to a new set of online rights to further protect Canadians’ privacy, such as data portability, explicit rights to delete online information (source takedown), and increased transparency about the use of automated decision-making.

We addressed some of our concerns about elements of the Digital Charter in last year’s blueprint, most notably related to the proposals on providing our office with “circumscribed” enforcement powers, and on exceptions to consent.

“Circumscribed” order-making – rather than broad order-making powers, which are common in most jurisdictions – is not only inefficient, but ineffective. Against the backdrop of a fast-moving digital economy where risks arise and evolve on a daily basis, it would cause delay and encourage limited compliance. In contrast, broad order-making powers would mean organizations would see an interest in complying, and provide Canadians with quick and effective remedies in cases of non-compliance.

We have also called for changes that would enable our office to impose administrative monetary penalties, rather than a framework that only envisions fines imposed by the courts.

In most other jurisdictions, notably the European Union and the United States, laws provide for significant administrative monetary penalties imposed by the regulator. There is no reason things should be different in Canada. Ontario has that power under its Personal Health Information Protection Act. Quebec’s Bill 64 proposes similar powers, as well as a number of provisions similar to those of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The bill is the most progressive legislative proposal in Canada of late.

We also remain concerned about the concept of an exception to consent for “standard business practices” as proposed under the Digital Charter. As defined, it is much too broad of a concept, one that risks becoming a catch-all exception, if not a gaping hole. Businesses should not be allowed to dispense with consent merely because a practice is one they determine to be “standard.”

Our law reform proposals include exceptions to consent that would facilitate innovative uses of technologies where consent is not possible, and our proposed preambles and purpose statements for PIPEDA would serve to recognize the legitimate interests of businesses, but within a rights-based framework.

The Commissioner wrote to several key cabinet members in the weeks that followed the last federal election. He shared with them his advice on how to achieve the objective of protecting Canadians’ rights in a way that fosters trust and innovation, and has subsequently had the opportunity to discuss the issue with them further. We remain committed to continue working with government on these issues, and look forward to the opportunity to be engaged in the review of specific legislative proposals.

On the public sector side, the government has plans to advance the Data Strategy Roadmap for the federal public service, which includes an engagement to strengthen data privacy protections as well as to increase government use of data and automated decision-making.

In parallel, the Department of Justice has engaged targeted stakeholders about modernizing the Privacy Act through a series of discussion papers. We responded to the Department’s consultation on Privacy Act modernization in December 2019.

The Government of Canada’s National Data Strategy Roadmap focuses heavily on “unlocking the value” of data. It states that data have the power to enable the government to make better decisions, design better programs and deliver more effective services for the public.

In order to optimize the value of data and create efficiencies there is a focus on increased sharing, both between government departments and between the public and private sectors.

The public and private sectors are increasingly working together in developing standards, in the storage of government data and in delivering digital government programs to the public, among other activities. Given this greater focus on public-private partnerships, it is important that both our federal statutes adopt similar principles. The public sector should not be held to a different standard than the private sector. In fact, it should be a leader in privacy protection.

In our submission in response to the Department of Justice consultation, we recognized that technology can provide better services to Canadians and help achieve important public interest objectives. We provided advice on how the Privacy Act could be modernized to ensure privacy rights and Canadian values are respected, consistent with our blueprint.

These key issues we identified for law reform are proving to be all the more relevant in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, and the move towards digital government in general, which only serves to reinforce the need for modernized federal privacy laws.

Further reading

- Review of the Privacy Act – Revised recommendations, November 2016

- CIRA, Canadians Deserve a Better Internet, May 2020

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, Strengthening privacy for the digital age: Proposals to modernize the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, 2019

- Privy Council Office, Report to the Clerk of the Privy Council: A Data Strategy Roadmap for the Federal Public Service, 2018

- Department of Justice Canada, Modernizing Canada’s Privacy Act – Engaging with Canadians on Privacy, 2019

Ongoing policy work

Since the publication of our blueprint, our office has continued its policy analysis of both federal privacy laws with a view to providing further advice on legislative reform.

Artificial intelligence presents fundamental challenges to all of PIPEDA’s privacy principles. Responsible innovation involving artificial intelligence systems must take place in a regulatory environment that respects fundamental rights and creates the conditions for trust in the digital economy.

In early 2020, we launched a public consultation to seek input on protecting Canadians’ rights as artificial intelligence expands.

As part of our consultation, we issued a discussion paper containing key proposals for PIPEDA reform that would bolster privacy protection and achieve responsible innovation involving artificial intelligence systems. We sought input on a number of targeted questions in order to elicit feedback from experts in the field as to whether our proposals would be consistent with the responsible development and deployment of artificial intelligence systems.

As we noted in the discussion paper, we are paying specific attention to artificial intelligence systems given their rapid adoption for the purpose of processing and analysing large amounts of personal information. Their use for making predictions and decisions affecting individuals may introduce privacy risks and discrimination.

As with other technologies, artificial intelligence comes with both benefits for the public interest and risks for human rights.

For example, artificial intelligence has great potential in improving public and private services. It has helped spur new advances in the medical and energy sectors. However, the impacts to privacy and human rights will be immense if legislation does not include clear rules that protect these rights against the negative outcomes of artificial intelligence and machine learning processes.

The input we have received from stakeholders through this consultation will serve to refine our thinking and make our law reform proposals more relevant.

Further reading

Recent investigations and law reform

As with last year, a number of investigations discussed in this annual report highlight gaps and other shortcomings in the current legislative framework.

For example, under The Privacy Act: A year in review, we summarize our investigation into a leak related to a Supreme Court nomination. The complainant requested that we investigate the roles of various institutions, some of which are under the jurisdiction of the Privacy Act, and others that are not. Our investigation was constrained by the jurisdictional limitations of the Act.

The Privacy Act section of this report also describes follow-up work related to an investigation into Statistics Canada’s use of detailed financial information about millions of Canadians. The investigation had found the initiatives did not respect the principles of necessity and proportionality, which are recognized globally as fundamental privacy principles but are not reflected in our federal laws.

Under The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act: A year in review, we examine issues related to protecting privacy in the context of outsourcing as part of investigations into TD Canada Trust’s and Loblaw Co. Ltd.’s transfers of customers’ information to service providers outside Canada for processing.

Also under The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act: A year in review, we summarize our investigation into RateMDs.com, a website where patients can rate and review health care professionals. This investigation demonstrates how the existing legislative framework is insufficient in upholding the reputational rights of Canadians in the digital economy.

Declarations in support of reform

Over the last year, our office has welcomed support for law reform to protect human rights from within Canada and beyond.

Privacy commissioners from around the world adopted a resolution on privacy as a human right and precondition for exercising other fundamental rights at their annual meeting last fall in Tirana, Albania.

The resolution from the recently renamed Global Privacy Assembly was an important step in the commitment to privacy as a human right worldwide.

The United Nations declared privacy an inalienable and universal human right in 1948, and in 1966 the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights reaffirmed the central role that privacy plays in democracy. Since then, over 80 countries worldwide have enshrined privacy rights for individuals in their laws and regulations.

The resolution noted growing support and increased calls from civil society, academia, media organizations, legal professionals and others to assert and protect privacy rights globally.

It called on governments to reaffirm a strong commitment to privacy as a human right and value in itself, and to ensure legal protections. It asked legislators to review and update privacy and data protection laws, and encouraged regulators to apply all relevant laws to activities in the political ecosystem.

Finally, it called upon businesses to show demonstrable accountability across commercial activities; civil society organizations (including media and citizens) to exert their privacy rights; and for all organizations to assess risks to privacy, fairness, and freedom before using artificial intelligence in their activities.

Closer to home, our provincial and territorial counterparts joined us at our 2019 annual meeting in endorsing a resolution on the need for effective privacy legislation in a data driven society.

We noted at the time that many access and privacy laws in Canada have not been fundamentally updated in decades. As a result, the level of privacy protection granted to Canadians has been outpaced by what many other countries provide to their citizens.

Further reading

- Global Privacy Assembly, International resolution on privacy as a fundamental human right and precondition for exercising other fundamental rights, October 2019

- Effective privacy and access to information legislation in a data driven society: Resolution of the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Information and Privacy Commissioners, October 2019

Legislative developments in Canada and beyond

Some jurisdictions around the world are seeing positive developments with respect to law reform.

Europe is taking stock of the GDPR after two years of implementation. The GDPR significantly raised the bar for privacy and showed us how a human rights-based law can work in practice. As we look to Europe, we see that companies there are continuing to operate successfully under the GDPR. Rights-based laws are not an impediment to innovation. To the contrary, they help to build the consumer trust necessary to support and drive an efficiently operating digital economy.

In the United States, various jurisdictions are adopting data protection laws – including in digital revolution hubs such as California and Washington State.

Closer to home, Quebec’s National Assembly is examining a bill intended to, in the words of the former Justice Minister, be “very closely modelled on European best practices” and “give more teeth” to the province’s data protection statutes.

With Bill 64, the Quebec government is proposing to grant citizens clear, enforceable rights such as the right to erasure, and to significantly increase the enforcement powers of the Commission d’accès à l’information (CAI), bringing its powers more in line with those of data protection authorities in other jurisdictions, including the European Union.

Conclusion

These are unprecedented times for Canada and countries around the world.

Getting privacy right during the pandemic will serve to build trust in public health institutions and in the public sector at large, as well as in the digital tools that are becoming essential to live safely.

As we said in our joint statement with provincial and territorial colleagues: “The choices that our governments make today about how to achieve both public health protection and respect for our fundamental Canadian values, including the right to privacy, will shape the future of our country.”

Social and economic recovery will not be sustainable unless the interests and rights of individuals are respected.

The Privacy Act: A year in review

Some of the files we worked on in 2019-2020 would have been inconceivable when the Privacy Act came into force more than 35 years ago. For instance, we advised the RCMP on the use of drones and DNA, investigated complaints on mass harvesting of private sector data by Statistics Canada, and discussed the privacy considerations of video recruitment with government departments.

In addition, we have continued to help federal institutions adopt privacy protective measures as they develop new initiatives. We redesigned our guide on PIAs with an eye to making it more practical, and engaged in outreach activities with institutions to help them better understand their obligations.

On the investigations side, we made great strides in reducing a backlog of cases. We achieved these results in part through enhancing our processes, and adopting a new approach when institutions are not responding to their personal information requests in a timely or adequate manner.

The following section highlights key initiatives under the Privacy Act.

Privacy Act enforcement

Operational updates and trends

In 2019-2020, we accepted 761 complaints under the Privacy Act. Although this seems like a significant decrease compared to the previous year, the change is mostly due to an evolution of our counting methodology towards enhancing accuracy and consistency.

We have adjusted how we track and report on complaints and investigation findings. Since April 1, 2019, when an individual’s complaint about a single matter represents potential contraventions of multiple sections of the Privacy Act, or when an individual complains following multiple access requests made to one institution, we track and report these as a single complaint.

In our view, this method more accurately represents the number of individuals raising privacy concerns, and provides a more consistent picture of our work across both the Privacy Act and PIPEDA.

We noted a decrease in complaints at the very end of the fiscal year, as the global COVID-19 pandemic spread to Canada. This was predictable and understandable given the magnitude of the public health crisis.

During 2019-2020, the majority of complaints we accepted were related to access to personal information (28% of accepted complaints) and to institutions failing to respond to access requests within the time limit required under the Act (45% of accepted complaints).

Of significant note this year are important reductions in our office’s response times for files that weren’t previously backlogged. This is due in part to the success and efficiency of our restructured intake and early resolution functions, which improved our early resolution process. These improvements were gained by implementing a new deemed refusal approach and by resolving a greater number of complaints through summary investigations where appropriate.

We also launched a new online complaint form, which has streamlined and automated our process for receiving and triaging complaints, resulting in greater efficiency and usability.

We have also continued to implement the deemed refusal approach to time limit complaints described in our previous annual report. Partly as a result of this approach, we have observed a sharp increase in the number of well-founded (and not resolved) complaints: in 2019-2020, we have found 177 complaints to be well founded, compared to 49 the previous year. Of these well-founded complaints, 146 were time limit complaints in 2019-2020, compared to 18 the previous year.

Deemed refusal approach

Federal institutions too often fail to meet their obligations to respond to personal information requests made under the Privacy Act within the specified time limits. Year after year, we receive many complaints from individuals alleging that a government institution unjustly denied them timely access to their personal information.

This past year, our office has taken firm steps to both: (i) incite superior engagement, responsiveness and timeliness on the part of institutions under investigation; and (ii) better empower complainants who raise issues of institutions failing to respond to personal information requests within the time limits provided in the Act.

We have therefore instituted our deemed refusal approach for time limit complaints, issuing deemed refusal findings to address situations where institutions are not responding in a timely or adequate manner, or are unable to commit to a release date for access to personal information requests.

A deemed refusal finding allows Canadians to exercise their right to apply before the Federal Court in a timely manner if they have faced challenges when attempting to access their personal information.

An important component of the deemed refusal approach includes a process to conditionally resolve complaints where an institution commits to responding to personal information requests within an acceptable period of time. This has resulted in the expedited conclusion of 191 complaints.

Unfortunately, institutions would not provide a commitment date in 146 cases, which resulted in deemed refusal findings. In 2019-2020, we issued deemed refusal letters to 11 government institutions, including 98 letters to Correctional Service Canada (CSC) and 30 to the RCMP. By comparison, in 2018-2019, we issued 31 deemed refusals against three government institutions (CSC, the RCMP, and Health Canada).

Owing to the approach, we were also able to resolve 372 complaints on an expedited basis without needing to apply a commitment date or issue a deemed refusal finding. In such cases, institutions responded promptly to resolve the complaint. The remainder of the complaints were either not well-founded or abandoned by the complainants.

Our deemed refusal approach has significantly reduced the treatment time of time limit investigations where we face resistance or lack of responsiveness from organizations, ensuring the investigation will not exceed a year.

On a government-wide level, it is evident that responding to Canadians' requests for access to their personal information remains a chronic and widespread problem. In our view, this is largely due to sub-optimal funding, prioritization, and resource allocation for this critical function by federal institutions.

Backlog reduction

Over the year, we made considerable progress in reducing our backlog of complaints. We are pleased to report that we reduced the overall backlog of Privacy Act complaints older than 12 months by 56%. Across both the Privacy Act complaints and PIPEDA complaints, the reduction was 50%.

We attribute this success to a new operational strategy and an increase in resources. Our strategy involved enhancing procedural efficiency and setting higher expectations with respect to institutions’ engagement, timeliness and responsiveness to our investigations. When combined with the increase to our office’s resources provided in the 2019 federal budget, the strategy allowed us to reach our backlog reduction milestones.

Specifically, we hired new staff and redistributed files, which increased capacity and allowed investigators to reprioritize and focus on aging files and those at risk of becoming backlogged. We also engaged consultants to lend regulatory expertise in sharing the backlog reduction workload.

Looking forward, we expect to reduce the backlog by 90% by the end of 2020-2021. To that end, we continue to adopt and refine enforcement strategies that demand timely and quality stakeholder engagement, which results in heightened protection of Canadians’ privacy rights, and mitigates the risk of similar backlogs in the future.

We have created a work unit that focusses specifically on the early resolution of complaints using various operational and administrative strategies. For example, we improved the early resolution process by shifting towards gathering information by phone in real time, which streamlined our efforts and reduced the delays associated with obtaining information in writing.

The early resolution unit also issues summary investigation reports, which are shortened investigations for typically straightforward matters that result in expedited findings, such as in the deemed refusal approach described above. Combining early resolution and summary investigations, the unit closed 60% of all accepted complaints under the Privacy Act, including time limit investigations.

Of the 1,335 Privacy Act complaints we closed in 2019-2020, 338 were handled through early resolution. The remaining 997 complaint files were closed as a result of regular or summary investigations, of which 751, or 82%, were well-founded. It is important to note that 654 of those well-founded complaints were time limit complaints, some of which were closed as per our new deemed refusal approach.

The high number of time limit complaints is a clear indicator that government institutions continue to face significant challenges in responding to access to personal information requests.

New online complaint form

In September 2019, we introduced a new, optimized and automated online complaint form for both Privacy Act and PIPEDA complaints. This created efficiencies by pre-populating complaint files, which in turn accelerates the triaging process.

The form provides complainants with relevant information as they progress through it. For example, it lays out our jurisdiction under federal laws, which allows complainants to quickly determine whether their complaint should be made to our office or to a provincial privacy authority.

This has contributed to a decrease in the number of complaints ultimately filed with our office, and to a significant reduction in complaints that fall outside our jurisdiction. As a result, complaint treatment times at the intake stage has been reduced, and the review process by early resolution investigators is more efficient.

Additionally, providing information to individuals as they fill out the form makes them more aware of the key supporting documents required. This has reduced the need to follow up with complainants to obtain necessary documents.

In the end, introducing the new form resulted in fewer and more relevant complaints, better access to necessary supplementary materials, and a more expedited handling of complaints by our office.

Post-investigation compliance monitoring

After expanding our compliance monitoring unit’s functions to include investigations under the Privacy Act in addition to those under PIPEDA, we can now more effectively follow how our office’s recommendations have been implemented across the public sector.

Since last year, the unit monitors whether the recommendations we made during key investigations under the Privacy Act are being applied, allowing us to assess whether federal institutions are meeting their commitments to our office and to Canadians.

In 2019-2020, eight complaints were directed to the compliance monitoring unit. This included our earlier investigations of the Canadian Transportation Agency and the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA), as well as follow-up work related to our 2019 investigation into Statistics Canada, which was summarized in our previous annual report to Parliament.

Statistics Canada

Our investigation focused on Statistics Canada’s use of detailed financial information about millions of Canadians, which the federal agency had acquired or was planning to acquire from private-sector organizations, in the context of two projects, namely the Credit Information Project and the Financial Transactions Project.

Statistics Canada ultimately agreed to follow our recommendations and did not implement the projects as originally designed. Our office is providing a full-time resource to support Statistics Canada in redesigning the projects to bring them to a level that meets our recommendations.

The agency has also been working with our office to develop and implement policies and procedures aimed at incorporating necessity and proportionality more broadly into its statistical methods.

Furthermore, at the invitation of the Chief Statistician of Canada, Commissioner Therrien participated in an international panel at a United Nations Statistical Commission event in March 2020. He presented the results of our investigation and highlighted their potential relevance for every statistical agency faced with similar data challenges and opportunities, and similar responsibilities to respect citizens’ privacy rights.

It should be noted that due in part to the old age and inadequacy of Canada’s laws to deal with 21st century privacy issues, our investigation did not find any legal violations.

However, we found that the two projects as originally designed did not meet necessity and proportionality requirements. The necessity principle is currently adopted as government policy at the federal level and is a legal principle in many jurisdictions across the world, but it is not included in the Privacy Act.

Our investigation into the agency’s use of administrative data collected or compiled by private-sector organizations also raises the importance of ensuring Canadians are protected through, at minimum, common privacy principles included in laws that govern both government and the private sector.

The growing role of public-private partnerships is becoming more apparent, and these partnerships create additional complexity and risk. Our investigation serves as an appropriate example of how the pursuit of laudable public interest goals can lead to highly privacy invasive results when privacy is not taken into account. Now more than ever, Canadians need legal assurance that their privacy rights are protected.

Further reading

- Statistics Canada – Invasive data initiatives should be redesigned with privacy in mind: Report of findings, December 2019

- Incorporating privacy into statistical methods – Necessity and proportionality: Address delivered by Daniel Therrien at the United Nations Statistical Commission Side Event, March 2020

Key investigations

Leak about Supreme Court candidate highlights need for law reform

In March 2019, media reports claimed that documents from an anonymous source demonstrated a disagreement between the Prime Minister and the Attorney General concerning the Attorney General’s recommendation of a candidate to the Supreme Court. The candidate subsequently provided a public statement stating that he had withdrawn his candidacy due to his wife’s health.

In the wake of these media reports, a Member of Parliament filed a complaint to our office alleging a breach of the Privacy Act. The complainant requested that we investigate the roles of the Privy Council Office (PCO), the Department of Justice, the Office of the Commissioner of Federal Judicial Affairs (CFJA), and the Office of the Prime Minister of Canada (PMO).

Our jurisdiction under the Act does not extend to the information handling practices of either the CFJA or the PMO. We therefore focused our investigation on the PCO and the Department of Justice.

According to the CFJA, following a Supreme Court appointment process led by an independent advisory board, the PMO was provided with a shortlist of candidates to consider. The PMO in turn provided the shortlist to the Attorney General who then consulted with stakeholders and advised the Prime Minister of the individual whom she recommended. Subsequently, the Prime Minister announced the nomination of the individual who was ultimately appointed.

During our investigation, we spoke with officials from the PCO, who confirmed their office does not play a role in identifying or assessing judicial appointment candidates. We gathered documentary evidence and testimony from the Department of Justice. We found no evidence the PCO or the Department of Justice had access to the information about the former Attorney General’s recommendation for appointment to the Supreme Court, and therefore found no evidence the disclosure originated from the PCO or the Department of Justice.

Accordingly, both the complaints against the PCO and the Department of Justice were deemed to be not well-founded.

While we did not find a contravention of the Act by the government institutions that fall under our jurisdiction, it is clear that a candidate’s privacy was compromised and negatively impacted by the disclosure of his personal information relating to the Supreme Court application and nomination process. This has resulted in injuries, not only to the reputation of the candidate, but as well, to the integrity and confidentiality of the judicial nomination process.

The fact that our investigation was constrained by the jurisdictional limitations of the Act, in our view, is yet another example of the need for legislative reform. Over the past several years, the Privacy Commissioner has requested on numerous occasions that the Act be amended to extend coverage to all government institutions, including Ministers’ Offices and the PMO. We believe this broadened jurisdiction would allow to us to fully investigate complaints such as this one.

Further reading

Privacy in a litigation context

When an individuals’ personal information is implicated in legal proceedings, the nature of the information is often particularly sensitive for the individual. The three investigations summarized below highlight the intersection between the open court principle and the protections under the Privacy Act.

Public disclosure of medical information during military trial consistent with Privacy Act

A former member of the military filed a complaint against the Department of National Defence (DND) in relation to the disclosure of his personal information during a military trial.

The complainant alleged he was required to publicly disclose medical information during a summary trial as part of his defence in relation to a charge against him. He alleged that since his request to be tried at court martial was declined, he was compelled to wrongfully disclose his medical information at the summary trial.

DND submitted that summary trial proceedings are subject to the open court principle, which generally requires such proceedings and related records before the court to be open and available for public scrutiny, except to the extent the court otherwise orders.

After reviewing the evidence, we concluded that the disclosure of the complainant’s personal information during the summary trial was consistent with the disclosure provisions in the Privacy Act.

The military justice system shares several underlying principles with the civilian justice system. One of these principles is that summary trials are public by default.

The complainant’s personal information disclosed to the public involved testimony in the context of the summary trial proceedings in order for the presiding officer to issue a finding as to whether there had been a violation of the military’s Code of Service Discipline, in accordance with the National Defence Act.

The Privacy Act allows for the disclosure without consent of personal information for the purpose for which the information was obtained or for a consistent use, as well as where disclosure is authorized by law.

For those reasons, we concluded that the complaint was not well-founded.

Nonetheless, we encourage government institutions to consider measures to ensure that participants in public hearings be advised, in advance, that information they disclose will be considered publicly available, and are aware of any steps that may be available to protect personal information from disclosure.

Further reading

Disclosure of personal information for litigation purposes permissible under the Privacy Act

A military member filed complaints against the Department of Justice and DND in relation to the disclosure of his personal medical information by DND to the Department of Justice for the purpose of defending against litigation filed by the military member.

The litigation involved a statement of claim filed in the Ontario Superior Court against DND for defamation and military police negligence. The Attorney General of Canada was named as the respondent.

In preparing to defend against the complainant’s allegations, legal counsel for the Department of Justice issued a document requiring DND to collect and produce all documents that may be relevant to the complainant’s lawsuit. The order specified, among other things, that the complainant’s physical and mental health files should be provided. DND disclosed the requested information to the Department of Justice.

The Department of Justice argued that the Privacy Act is not intended to restrict a federal institution’s ability to communicate personal information with its legal counsel in order to determine whether it must ultimately produce such information as being relevant to a civil proceeding.

The complainant took the position that while it is expected that DND would disclose certain information for the defence of his claim, the request for medical, mental health, and other health records was overbroad, overly intrusive, and a contravention of the Act. He also raised concerns related to doctor-patient confidentiality.

In our investigation, we found that having named the Attorney General of Canada in his statement of claim, the disclosure of the complainant’s personal information was for use in legal proceedings involving the Government of Canada and appears to have been directly relevant to the complainant’s legal claim. Therefore, we found that the disclosure and collection of personal information were consistent with the Privacy Act and considered the complaints to be not well-founded.

Further reading

CBSA’s disclosure of medical information to a third party leads to complaint

The CBSA sent an individual’s personal medical information to his bondsperson. The individual complained to our office that the CBSA contravened the disclosure provisions of the Privacy Act in doing so.

The complainant had become involved with the CBSA in the process of applying for refugee status or permanent residency status. As part of the process, he was a party to numerous actions before the Federal Court. In the Federal Court records, the complainant referred to changes in his health while in CBSA custody. These court files form part of the public record and are accessible to the public at large in accordance with the “open court” principle.

At one point during his ongoing application process, the complainant sought to have the CBSA amend the conditions of his bond. The CBSA sent a letter to the Immigration and Refugee Board, notifying it of the changes, with carbon copies to the complainant and to his bondsperson. The letter included details about the complainant’s allegation that he had suffered health consequences during CBSA detention. However, the complainant’s medical information was unrelated to the purpose of informing the bondsperson of the changes in the bond conditions.

Section 8 of the Privacy Act prevents a government institution from disclosing personal information under its control without consent except under specific circumstances. However, subsection 69(2) of the Privacy Act states that section 8 does not apply to personal information that is publicly available. Our office determined that the complaint was not well founded because the complainant’s medical information was publicly available through Federal Court records.

The meaning of the term “publicly available” is explored in the Federal Court of Appeal decision of Lukács v. Canada (Transport, Infrastructure and Communities), 2015 FCA 140, where the Court interpreted this term to mean “available to or accessible by the citizenry at large.”

However, it should be noted that if the complainant’s personal information had not already been publicly available in court records, the decision by the CBSA to send a copy of this information to a third party would have been a breach of the disclosure provisions of the Privacy Act. It is solely through the operation of subsection 69(2) of the Act that the complaint is not well-founded.

Further reading

Surveillance in the workplace

We regularly receive complaints related to workplace surveillance issues – in particular, employees raise concerns with respect to video surveillance, which can represent a particularly privacy intrusive collection of personal information.

Video recording in the workplace at correctional institutions

We received three complaints alleging that Correctional Service Canada (CSC) was using video footage to monitor employee performance in contravention of the Privacy Act.

The complainants alleged CSC improperly used their personal information when a manager reviewed video of their patrols. According to the complainants, the manager was using the video to monitor employee performance.

According to CSC, its purpose for using video surveillance is to maintain the security of institutions and to investigate incidents such as violence, allegations made against staff and overdoses.

In this case, an investigation into the death an inmate in custody had revealed deficiencies in patrols, and the CSC developed an action plan to address those issues. This plan included reviews of video of random patrols from a limited time period in order to identify systemic deficiencies.