Annual Report to Parliament 2013 on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Online Privacy Transparency

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street - 1st Floor

Gatineau, QC

K1A 1H3

(819) 994-5444, 1-800-282-1376

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2013

Cat. No. IP51-1/2013E-PDFThis publication is also available on our website at www.priv.gc.ca

Follow us on Twitter: @PrivacyPrivee

August 2014

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2013.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

August 2014

The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2013.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

About PIPEDA

The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, or PIPEDA, sets out ground rules for the management of personal information in the private sector.

The legislation balances an individual's right to the privacy of personal information with the need of organizations to collect, use or disclose personal information for legitimate business purposes.

PIPEDA applies across Canada to organizations that collect, use, or disclose personal information in the course of commercial activities, unless provincial privacy legislation deemed substantially similar to PIPEDA applies. Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia each have substantially similar legislation covering the private sector. In addition, Ontario, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador have substantially similar legislation covering certain organizations in the health sector.

In all provinces, PIPEDA applies in respect of federally regulated activities in the private sector. PIPEDA also protects employee information, but only in the federally regulated private sector.

Message from the Commissioner

It is becoming increasingly apparent that the protection of privacy demands a partnership between individuals and the corporations with which they interact.

Like any successful partnership, this must be based on trust and therefore openness. Now that personal data has become such a precious coin of commerce, the rules governing its collection, use and disclosure must be crystal clear, well understood, and actively accepted.

As I begin my term as Privacy Commissioner of Canada, I am proud that this organization has sought to take a leadership role in fostering this important relationship between customers and businesses. One of our key objectives going forward will continue to be helping to ensure that enterprises are forthright about their privacy practices, so that Canadians know what to expect and can play a more meaningful role in safeguarding their personal information.

In today’s increasingly digitally driven, information-based economy and society, enhancing the ability of individuals to take greater control over their personal information means enhancing their control over their lives.

This report describes how the Office worked toward that goal under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act during the 2013 calendar year.

It demonstrates how this Office turned research into action by identifying emerging privacy issues, developing policy positions followed by guidance and then enforcement.

This report also shows that effective regulatory action and results are possible even in dealing with global issues in an increasingly borderless world. In such a world, privacy protectors more and more need to combine forces with international counterparts to both flag privacy concerns (as the Office did in a letter signed by 36 counterparts regarding Google Glass) and take joint action leading to improved online privacy practices (which took place with the inaugural Internet Privacy Sweep with 18 other data protection authorities allied under the banner of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN)).

This year’s report also shares stories flowing from investigations of complaints, addressing systemic issues.

At the same time, it also underlines outreach efforts, providing guidance to help businesses steer clear of privacy pitfalls, while continuing to educate Canadians about contemporary privacy risks, and the steps they can take to better protect themselves.

Technological Turbulence

As has become a general norm, many of 2013’s privacy challenges were rooted in new and emerging technologies—technologies including facial recognition software, wearable computing, cloud computing, online behavioural advertising, always-on smart phones, geo-spatial technology, advanced analytics, unmanned aerial vehicles (or drones) and genetic profiling. The Office sought to pinpoint the potential risks to privacy, which can be magnified by the fact that, increasingly, new technologies don’t generally operate in isolation. Instead, device and data sources merge and converge, spilling out new forms of digital information that can be detailed, persistent, and—at least in theory—infinitely and perpetually accessible.

This highlights the need for cooperation among regulators to ensure privacy protection beyond discrete informational transactions to address the global reach of organizations that have the capacity to collect and use virtually limitless amounts of personal information.

And it’s not just companies that are interested in data about individuals for their commercial purposes. More and more, it has been observed that personal information originally collected by the private sector can also flow into the hands of public sector agencies dedicated to law enforcement and national security. The need for a constructive debate around greater transparency and accountability on all sides is evident. And a special report from the Office tabled in Parliament in January 2014 made recommendations seeking to shape and contribute to this discussion.

Evolving Investigative Process

While it is understandably beyond many individuals to fully comprehend all the complexities of these challenges, one axiom holds true: Canadians value their privacy. They have told this Office so through regular public opinion polling along with hundreds of complaints every year alleging infringement of their privacy rights.

In 2013 the Office continued to apply a triage approach to ensure the optimal treatment for each of the 426 cases for review, an increase from 220Footnote 1 the year before. This approach pinpoints the most pressing and novel privacy issues, in the hope that lessons can be learned from them and widely shared. Of the complaints received, a very high number were about changes to Bell's privacy policy and were folded into one Commissioner-initiated complaint. A total of 133 complaints were successfully treated through the Office’s Early Resolution stream, where specially trained investigators used mediation, conciliation and other strategies to arrive at a more expedient and mutually agreeable solution.

In the end, formal findings were generated in 67 investigations. It was determined that 24 of the complaints were not well-founded, while 35 were well-founded but entirely or at least conditionally resolved. In eight further cases, however, the Office was not satisfied that the organization resolved the well-founded issues that were raised in the complaints. In such cases, respondent organizations were urged to take the steps necessary to comply with our recommendations.

Focusing on transparency

In several of the key actions taken in 2013, transparency was central. In one investigation conducted in 2013 (which we feature on page 22), it was found that Apple was not being transparent in collecting payment information from users to create Apple IDs even though certain apps were available to download at no cost. Following an investigation, the company committed to address the issue.

Meanwhile 2013 included two investigations in regard to the online behavioural advertising practices of two tech titans. And these results stemmed directly from the Office’s work in earlier years to develop a policy position and guidance on what we had identified then as an emerging practice.

In one found on page 13, Apple ended-up strengthening its privacy practices by giving users of iPhones, iPads and iPods greater control over the information collected about them for advertising purposes, making such controls more accessible and by conveying clearer information on how the company served up targeted ads.

In another investigation summarized on page 11, it was found that sensitive health information was being used inappropriately to better target ads delivered via Google’s advertising service. Google pledged to guard against such occurrences through more robust controls over the delivery of ads on its platform. It was concluded that the complaint was well-founded and conditionally resolved.

Outside the realm of investigations, transparency results were achieved with GPEN counterparts, reviewing privacy policies and information on over 2,000 websites and apps to see how understandable they were for users. While this exercise revealed transparency concerns (including with nearly half of the 300 Canadian-based sites surveyed), the public exposure and dialogue that these efforts generated led to several dozen organizations improving the information they provide online about their privacy practices.

An Eye to the Future

In this era of continuing technological and social change, the most successful organizations are those that can spot new opportunities, including innovative new sources and uses of personal information.

Our job is to be equally nimble, to understand what’s happening today, and to anticipate what tomorrow will bring. Under its research and policy-development mandate, the Office works hard to identify current and emerging risks to privacy, develop positions and provide guidance.

Thus, for instance, a research paper published in 2013 explored the growing use of automated facial recognition technologies by the public and private sectors, and the implications for identity integrity in the real and online worlds.

Another paper looked at the increasing access by law enforcement to customer subscriber information held by private sector companies. More specifically, this paper examined, from a technical perspective what an IP address can reveal about a specific person.

And a third looks at the privacy challenges posed by wearable computers, with Google Glass being only one early example of what could become a major trend.

The Office also funded 10 new projects under our popular Contributions Program, an arm’s length funding program for external researchers. In the years ahead, these will help illuminate the privacy implications of police background checks, credit-reporting services, consumer health websites, direct-to-consumer genetic testing and other technologies and services.

A Final Note

Privacy Priorities

Reflections on the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada's Strategic Priority Issues

I know that December 2013 marked the conclusion of 10 remarkable years of leadership by Jennifer Stoddart. PIPEDA was only just coming into full force when she was appointed Privacy Commissioner. Many of the private-sector privacy protections that Canadians have come to cherish over the past decade are a testament to her bold vision, and her unflinching determination to carry it out. Many of the achievements garnered during her tenure were featured in a report released in October 2013 which told the story of how four strategic privacy priorities (public safety and privacy; information technology and privacy; identity integrity and protection; and genetic information and privacy) served to guide the Office’s work during a time marked by a constantly changing privacy landscape.

As a result, this Office is more than proud to dedicate this report to her.

I would also like to take this moment to acknowledge Chantal Bernier, who gained respect for her unparalleled work ethic and passion for privacy during both her term as Assistant Commissioner from 2008 to 2013, and then as Interim Privacy Commissioner upon Jennifer Stoddart’s departure.

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

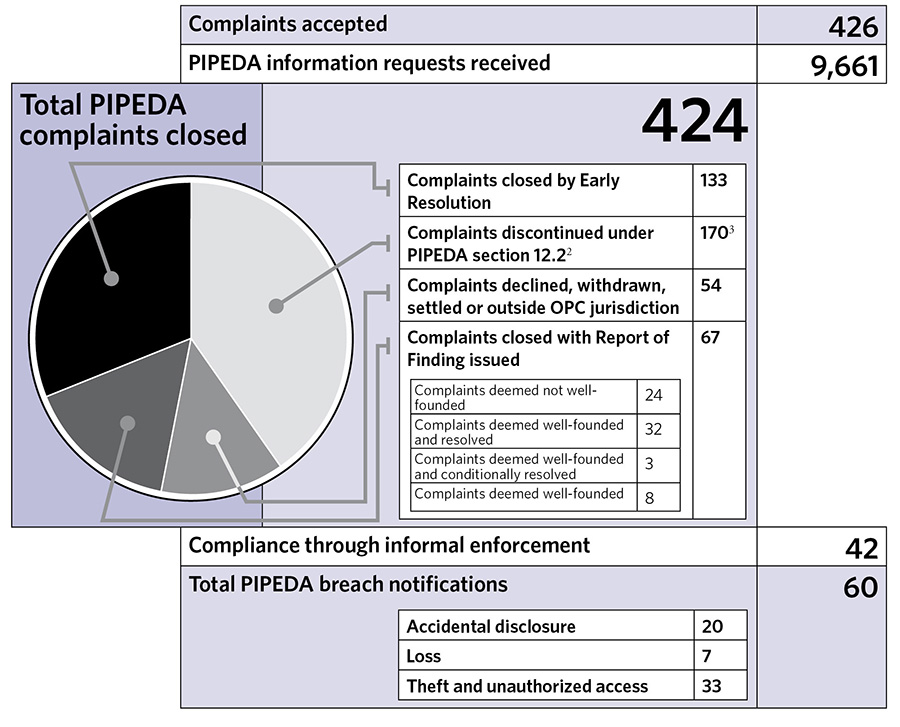

Privacy by the Numbers in 2013

Text version

Privacy by the Numbers in 2013 - Part 1

- Complaints accepted: 426

- PIPEDA information requests received: 9,661

- Total PIPEDA complaints closed: 424

- Complaints closed by Early Resolution: 133

- Complaints discontinued under PIPEDA section 12.22: 1703

- Complaints declined, withdrawn, settled or outside OPC jurisdiction: 54

- Complaints closed with Report of Finding issued: 67

- Complaints deemed not well-founded: 24

- Complaints deemed well-founded and resolved: 32

- Complaints deemed well-founded and conditionally resolved: 3

- Complaints deemed well-founded: 8

- Compliance through informal enforcement: 42

- Total PIPEDA breach notifications: 60

- Accidental disclosure: 20

- Loss: 7

- Theft and unauthorized access: 33

2 Under section 12.2 (1) of PIPEDA, the Commissioner may discontinue the investigation of a complaint if the Commissioner is of the opinion that (a) there is insufficient evidence to pursue the investigation; (b) the complaint is trivial, frivolous or vexatious or is made in bad faith; (c) the organization has provided a fair and reasonable response to the complaint; (d) the matter is already the object of an ongoing investigation under this Part; (e) the matter has already been the subject of a report by the Commissioner".

3 Of these complaints 166 were regarding changes to Bell's privacy policy, a matter made the subject of a Commissioner-initiated complaint which has resulted in an investigation of concerns raised.

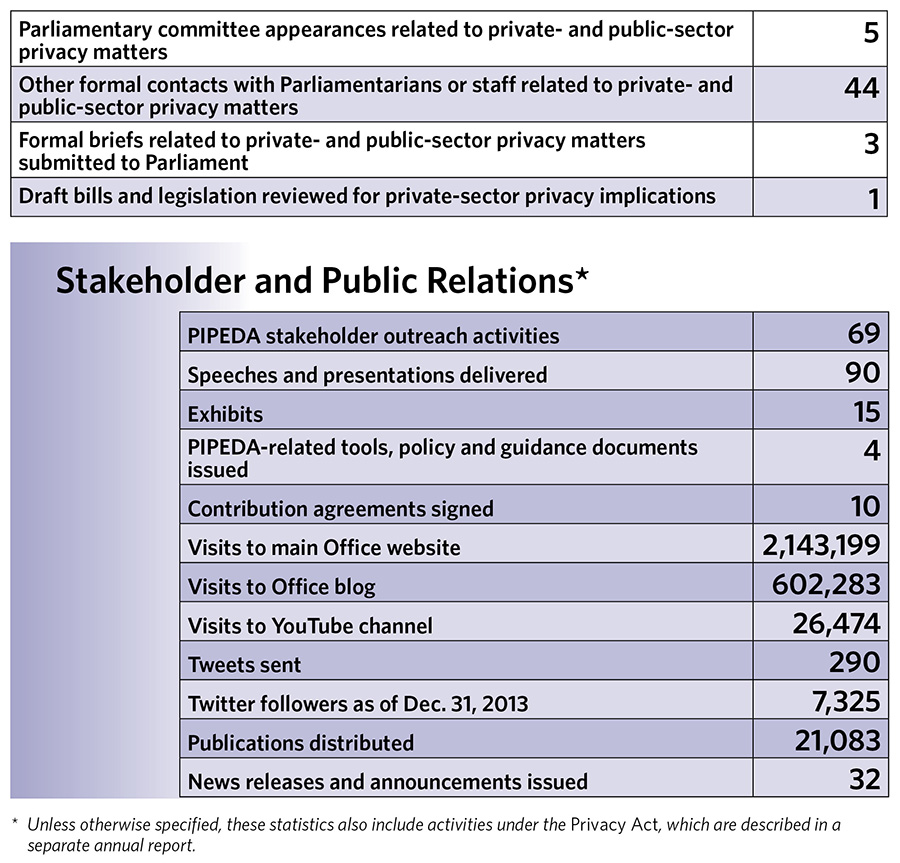

Text version

Privacy by the Numbers in 2013 - Part 2

- Parliamentary committee appearances related to private- and public-sector privacy matters: 5

- Other formal contacts with Parliamentarians or staff related to private- and public-sector privacy matters: 44

- Formal briefs related to private- and public-sector privacy matters submitted to Parliament: 3

- Draft bills and legislation reviewed for private-sector privacy implications: 1

Stakeholder and Public Relations *

PIPEDA stakeholder outreach activities: 69

Speeches and presentations delivered: 90

Exhibits: 15

PIPEDA-related tools, policy and guidance documents issued: 4

Contribution agreements signed: 10

Visits to main Office website: 2,143,199

Visits to Office blog: 602,283

Visits to YouTube channel: 26,474

Tweets sent: 290

Twitter followers as of Dec. 31, 2013: 7,325

Publications distributed: 21,083

News releases and announcements issued: 32

* Unless otherwise specified, these statistics also include activities under the Privacy Act, which are described in a separate annual report.

The Year in Review

With PIPEDA well into its second decade and privacy principles thoroughly entrenched within the private-sector landscape, it might seem that the Office had earned a chance to sit back and comfortably take stock of progress and achievements.

Quite the contrary.

Privacy rights are under constant challenge, especially from new and changing technologies, and emerging business models. Defending those rights demands vigilance and the creative use of our resources.

While we continued to carry out our traditional roles, including supporting Parliament on privacy issues and conducting investigations into complaints from individuals, we also sought to broaden our impact through innovative approaches to our work.

And so we concentrated on making the greatest use of the powers we already have, while also looking for new and efficient ways to promote alternative and effective ways to promote compliance outside formal investigation. Recognizing that most organizations want to do the right thing, we continued to reach out to stakeholders with information, tips and guidance. We also extended and amplified our impact by building strategic collaborations with partners in Canada and around the world.

Mindful, however, of the limitations inherent in an increasingly outdated legislative framework, we also continued to press for reforms to PIPEDA that would bring our enforcement powers more in line with the global norm.

Key results of these efforts are highlighted below.

Research and Policy

Over the years, our Office has grown into a world-renowned centre of expertise on emerging privacy issues. We continue to broaden and reinforce this expertise by researching trends and technological developments; monitoring legislative and regulatory initiatives; developing policy positions that advance the protection of privacy rights; and providing legal, policy and technical analyses on key issues.

Under PIPEDA, our Office has an explicit mandate to conduct and publish research on privacy issues. The dissemination of such knowledge is vital to our mission of promoting and protecting the privacy rights of individuals.

Over the past year, our efforts culminated in developing key research papers relevant to our private-sector mandate. These papers sought to explore the privacy implications of emerging issues and technological trends that may seem small today but look to loom larger and larger in years to come.

In particular, many developments have the capacity to further integrate surveillance (often of the surreptitious variety) into daily life. In fact, many have the potential to download the tracking traits of the online world into our offline reality, rendering what's largely anonymous today to be identifiable in the future:

- Automated Facial Recognition in the Public and Private Sectors explains how the human face is a uniquely measurable characteristic of our bodies, which makes it key to our identity. Facial recognition technology has become a viable and increasingly accurate method to tie our online activities to our real identities. When used for commercial purposes-especially surreptitiously-the technology raises questions about whether individuals can meaningfully consent to the collection, use or disclosure of this sensitive personal information.

- Wearable Computing: Challenges and Opportunities for Privacy Protection explains that, while only a few examples of wearable computers are currently on the market, many more are likely to be launched in the near future. The paper provides an overview of the wearable computing phenomenon, and some of its privacy implications. It also outlines the computing design considerations that ought to be built into such products in order to strengthen privacy protections.

- What an IP Address Can Reveal About You resulted from the Government of Canada having tabled various iterations of so called lawful access legislation over the past decade. In order to address the privacy impacts of allowing warrantless access to subscriber data such as one's IP address, this paper shared the results of our technical analysis. In short, it was found that subscriber data can be used to unlock additional information to develop very detailed portraits of individuals; providing insight into one's activities, tastes, leanings and lives.

Investigations

Our Office accepted 426 complaints from individuals concerning private-sector privacy issues in 2013. Of those, 166 complaints related to a new marketing initiative from Bell Canada as announced on October 23, 2013. We grouped those together and substituted a single Commissioner-initiated complaint, expected to be closed in 2014. Even when those complaints are subtracted from the total, our Office saw a 17 percent increase in our PIPEDA-related complaint load in 2013, compared to the year before.

Of the 424 complaints we closed in 2013, only 67 required the issuance of a formal report of finding. That marked a decrease of 84 reports of finding that we issued the year before. The remaining 357 cases were closed through early resolution and other statutory measures.

The number of breaches reported to our Office increased to 60 in 2013-up significantly from the 33 we dealt with the year before, but not out of line with other recent years.

Maximizing the impact of our investigations

In 2013 we conducted several investigations that revolved around privacy issues with the potential to affect a large number of users in Canada and around the world. Three cases are highlighted here.

Case Summary: Google moves to curb privacy-intrusive ads

A man who had searched online for medical devices to treat sleep apnea was shocked when ads for such devices popped up as he later browsed completely unrelated websites. He asserted that he had not consented to the collection and use of his sensitive health information for this purpose.

In an investigation (from which we benefitted from collaboration with the U.S. Federal Trade Commission), we determined that, as the complainant researched information on continuous positive airway pressure machines (used to facilitate breathing during sleep), a software cookie was installed in his browser. The cookie triggered ads for sleep apnea devices to appear when he visited other sites that had nothing to do with the sleep disorder. The other sites however, each used Google's advertising services.

Our Office's online behavioral advertising guidelines state that advertisers should avoid collecting health or other sensitive personal information for the purpose of delivering tailored ads.

Google requires all advertisers using its service to agree to specific policies, which prohibit all forms of interest-based advertising involving sensitive categories such as health information. However, Google acknowledged that some advertisers using its platform did not comply with the corporation's policy.

Our investigation found that the use of sensitive personal information in this manner did not correspond to the wording stated in Google's own privacy policy. Further, the investigation identified shortcomings in the way the company monitors its advertisers and made several recommendations for remedial actions to stop privacy-intrusive ads. Google committed to implement the recommendations by June 2014. Our Office has since received an update from Google outlining the remedial measures put in place and we are satisfied that Google has addressed our recommendations.

Case summary: Online money-transfer service revises validation procedures

An individual who had been using an online money-transfer service for four years was upset when the service advised him that he had to provide a bank account number that he had not previously been obliged to furnish. He complained to our Office.

Our investigation found that, to begin using the service to send money, users had to provide only some basic personal information, and to link a payment method, such as a credit card, to their service account.

We also learned that the service tries to reduce fraud losses by applying a risk-based calculation to establish an initial limit to the cumulative amount that users can initially send over the service. When the limit is reached, users are required to validate their identities with additional information-specifically, the particulars of a bank account-before the sending restrictions may be lifted. Users do not, however, have to use that bank account for future transactions; they may continue to use their original credit card or other payment option.

We concluded that it was reasonable for the service to adopt security measures to reduce financial risk, and sending limits and user validation procedures were valid tools for this purpose.

However, given the sensitivity of personal banking information, we found the lack of alternatives to validate user identities to be unacceptable. Indeed, the service's own user service agreement and privacy policy hinted at the existence of alternate validation measures. We also found that information on the service's website related to sending limits and the reasons they were imposed was inadequate.

We were, however, pleased that the service agreed to implement our recommendations by November 2014. It proposed a solution that, once successfully implemented, would no longer require users to provide their personal banking information, except where required by law. It would also clarify details of its revised procedures on its website, so that users could meaningfully consent to the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information.

Case summary: Apple called upon to provide greater clarity on its use and disclosure of unique device identifiers for targeted advertising

An individual alleged that Apple was using and sharing her personal information in the form of a unique device identifier (UDID) without consent for tracking purposes. Apple assigns a UDID to each iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch (iOS Devices) prior to sale. The company maintained that a UDID was not personal information because it alone couldn't be used to identify a user. However, because our investigation revealed that Apple also had access to Apple ID account details for each iOS Device user, we viewed UDID as personal information.

Apple explained that it used UDID for administrative and maintenance purposes. In that context, we did not consider the identifier to be sensitive information and we were satisfied that Apple had adequately explained such practices via general explanations in its privacy policy.

On the other hand, we found that UDID was also used by Apple, and disclosed to third party app developers (via Apple's iOS operating system), for the purpose of delivering targeted advertising to iOS Device users. In that context, we viewed UDID to be sensitive personal information as it could serve the same purposes as a persistent cookie and be used to create a detailed user profile. While we found that Apple offered easily accessible opt-out options regarding the use of UDID in the delivery of targeted advertising, we found Apple's explanations (which were comprised mainly of broad generalized statements in its privacy policy) to be insufficient. As a result, we recommended that Apple provide notice in a clear and prominent "just-in-time" way to shed proper light on the practice for users.

During the course of our investigation, Apple ceased using UDID for advertising and phased out the disclosure of UDID to app developers. Apple replaced UDID with Ad ID, for advertising. Apple then added the option for users to easily and immediately reset Ad IDs which effectively erases a user's history tracked by the identifier and shared with advertisers. Further, we were pleased to see that Apple implemented, in iOS 7, our recommendation that users be able to more easily find switches within their iOS Device privacy settings to reset that Ad ID and opt-out of receiving targeted ads.

Because of these developments, and because of Apple's general explanation about the functioning of Ad ID in its privacy policy supplemented by a more specific explanation available via a link in device privacy settings, we found the complaint to be well-founded and resolved.

Working with global partners

The inaugural Internet Privacy Sweep, which we developed and led in collaboration with partners in the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, is described in a feature article on page 23 of this report.

To leverage the impact of our own efforts to protect and promote privacy rights, we continued in 2013 to build formal and informal ties with provincial and international counterparts. For instance, we entered into a bilateral information-sharing agreement with Uruguay, adding to our existing partnerships with the UK, the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany and the multilateral Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) group.

Here at home we continued to collaborate on many levels with provincial counterparts that have substantially similar private sector privacy legislation in Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec.

Such joint approaches served us especially well when it came to data spills. Indeed, 2013 saw numerous jurisdictions grappling with breaches affecting millions of people worldwide. In one incident involving social media company LivingSocial, we worked with provincial and international counterparts toward a very positive conclusion.

Case Summary: Social media company strengthens safeguards after data breach

LivingSocial links businesses worldwide to potential customers via an Internet-based platform. In April 2013 the company advised us that cyber-intruders had obtained access to users' names, e-mail addresses, birthdates and passwords. More than 1.5 million Canadians were affected.

Given the magnitude of the breach, we engaged in a structured dialogue with the company, in co-ordination with the privacy offices of Alberta, British Columbia and Quebec, as well as with the UK Information Commissioner's Office.

This gave us rapid insights into the breach's impact on users, as well as the company's responses. We made some recommendations for remedial actions, which LivingSocial agreed to implement.

We were pleased by the company's responsiveness and commitment to strengthen its safeguards.

Making efficient use of our existing powers

Early resolution of complaints

We applied our early-resolution strategies to resolve 133 complaints in 2013, up 16 percent from the year before. Our approach is to identify prospects for early resolution quickly, and set a firm deadline for reaching a settlement. If a complaint cannot be resolved within the set timeline, it is referred to the investigations unit.

Recognizing the benefits of dealing with complaints in a timely, consensual and cost-effective manner, most complainants and respondent organizations appreciate this option.

BOOSTing Service

To further augment the quality of service we deliver to Canadians, we embarked on a multi-year initiative called "BOOST", which stands for Building on our Strengths and Talents. BOOST is about finding the most appropriate way to deal with a complaint or breach report, whether through structured discussion with the organization involved, an investigation, an audit, or using one of the other mechanisms available under the legislation. The initiative also seeks efficiencies at every stage of our activities, from the first moment a complaint or data breach comes to our attention until the case is closed. One measure of the success of BOOST is that the average time it took us to handle privacy complaints shrank to 5.3 months in 2013, down from 8.3 months the year before.

Example: PIN-pad privacy concerns resolved

A customer obtaining a refund from a computer store inserted his credit card into the card reader and was prompted to enter his personal identification number, or PIN. He was displeased to see his confidential number appear on the PIN-pad screen. The customer raised his concerns with our Office.

The storeowner said he was unaware of problems with the card reader. In further testing of the device, neither the storeowner nor the payment processor could duplicate the customer’s experience. Nonetheless, the payment processor replaced the device and assured us he would watch for further problems. The customer was satisfied with the outcome.

Example: Telecom company halts unwanted communications

A customer of a major mobile telecommunications company was annoyed to receive its marketing texts and calls and repeatedly sought the company's assurance that they would cease. When he continued to receive them, however, the customer contacted the Commissioner for Complaints for Telecommunications Services for help.

He ultimately also asked us to intervene. In response to our inquiries, the telecom company launched an internal probe. It found that customer care staff were using outdated and ineffective processes to shield customers from unwanted marketing material.

Staff were duly retrained in the more current processes. A glitch in the way the company's computers flagged customer preferences for marketing materials was also detected and fixed. With the retraining and IT issues resolved, we closed the complaint to all parties' satisfaction.

Declining or discontinuing investigations

Under section 12.2 (1) of PIPEDA, the Commissioner may discontinue an investigation of a complaint if he or she is of the opinion that (a) there is insufficient evidence to pursue the investigation (b) the complaint is trivial, frivolous or vexatious or is made in bad faith (c) the organization has already provided a fair and reasonable response (d) the matter is already the object of an ongoing investigation by the Office, or (e) the matter has already been the subject of a previous investigative report.

We continued in 2013 to focus our resources on investigations that raised systemic, complex or novel issues posing the greatest privacy risk to Canadians. As a consequence, we invoked our authority to decline or discontinue an investigation as set out in PIPEDA 170 times. Of those, 166 cases related to a marketing initiative that Bell Canada announced in the fall. We incorporated the concerns raised in those complaints into a single Commissioner-initiated complaint to allow for an efficient and targeted investigation, and discontinued the others. Through this approach, our Office is able to address the concerns raised by complainants in a manner that uses public resources more efficiently than treating separate, similar complaints one-by-one.

Promoting compliance through alternate tools

Stakeholder outreach

Our Office continues to nurture its positive relationships with businesses, industry associations and other stakeholders. Although we also conduct complaint investigations from our Toronto office, its original primary focus was to promote proactive compliance with PIPEDA through outreach activity.

Our engagement with organizations headquartered in the GTA via our Toronto office also enables us to keep our ear to the ground on emerging privacy issues. Such intelligence-gathering helps us fine-tune our research, policy work, and educational and outreach resources, to render them most relevant to stakeholders.

In 2013, our Toronto office undertook 69 outreach activities, including:

- a second annual meeting with GTA-based privacy lawyers and other sector-specific learning events centred on emerging privacy issues;

- a presentation to the Conference Board of Canada's Chief Privacy Officers Group, focused on the PIPEDA investigations process and workplace privacy;

- an opportunity for chief privacy officers to discuss issues of interest with the Commissioner and Assistant Commissioner, as well as the Information and Privacy Commissioners of Alberta and British Columbia;

- presentations to privacy professionals headquartered in the GTA through the International Association of Privacy Professionals' KnowledgeNet series, with the goal of de-mystifying the investigative and early-resolution processes and encouraging proactive engagement with our office;

- meetings with foreign-based retailers entering the Canadian market;

- participation in trade shows and conferences to further understanding of privacy issues.

Top-10 tip sheets

We also continued to publish easy-to-follow, pragmatic privacy advice in the form of Top-10 lists of tips. When our Ten Tips for Avoiding Complaints to the OPC proved popular, we released Ten Tips for a Better Online Privacy Policy and Improved Privacy Practice Transparency in 2013.

The tip sheets, which answer a request from industry, give organizations of all sizes an accessible entry point for the more detailed guidance, research and investigative findings that we also produce.

Guidance and Tools

In 2013, we continued development of our PIPEDA Interpretation Bulletins. We added two more on form of consent and publicly available information. They join a library of bulletins that codify interpretation of key terms in PIPEDA issued by the Courts and our Office.

In collaboration with provincial colleagues, we developed guidance to help organizations obtain meaningful consent for the online collection, use and disclosure of personal information.

In May of 2013, we used the occasion of Emergency Preparedness Week to launch our Privacy Emergency Kit. Developed in consultation with provincial and territorial privacy oversight offices across Canada, the kit aims to help organizations subject to federal privacy laws consider privacy issues in advance of a crisis.

We also developed guidance on an issue we began to increasingly see rear its head in complaints: managing the personal information related to accounts of individuals from the same family or residence. It seeks to ensure account holder information is updated promptly and accurately to avoid, for example, sensitive information being mistakenly disclosed to an estranged spouse.

Contributions Program

Once again this year, our Office funded privacy-related research projects conducted by universities and other partners. The 10 projects funded under our Contributions Program in 2013 examined everything from unmanned aerial vehicles and police background checks to consumer health websites and direct-to-consumer genetic testing services. There were also examinations of financial aggregation applications and platforms and services offered by credit reporting agencies. Two projects focused specifically on youth privacy issues.

During the year, we also put together a publication entitled Real Results, which featured the real, practical outcomes of selected projects funded under the Contribution Program and the positive impact they have had in enhancing privacy protection in Canada.

PIPEDA and the Road Ahead

This report describes our Office's efforts in 2013 to carry out our mission in the face of escalating challenges to the privacy rights that Canadians hold dear. In Canada and around the world, powerful information and communications technologies, coupled with the social and political demands of engaged citizens and consumers, are straining privacy frameworks developed for an earlier, simpler time.

Against this challenging backdrop, we have sought to deploy our resources in the most strategic and effective way possible, and to collaborate wherever feasible with partners in Canada and elsewhere. And we are conducting forward-looking research and preparing guidance to help organizations better protect personal information.

But we could do so much more with a legislative framework more suited to today's complexities. And so we continued in 2013 to call for reforms to PIPEDA that would include appropriate incentives to encourage organizations to comply.

Such incentives would, for instance, encourage more organizations to build privacy protections into their products and services right from the start, rather than waiting for problems to develop later in the marketplace.

More robust accountability and transparency requirements, backed by a meaningful enforcement regime, would also ensure that Canadians' personal information is appropriately protected in today's globally-connected environment.

In a sign that the international community is grappling with the identical challenges, the OECD released revisions to its seminal Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Trans-border Flows of Personal Data. The revisions expanded on the concept of accountability in privacy protection, urging organizations to demonstrate they have mature, functioning privacy programs in place.

The revisions, which were strongly influenced by the advice of an expert group led by former Privacy Commissioner Jennifer Stoddart, also counsel member countries to implement mandatory breach notification, and call for privacy authorities to be given the governance tools, resources and technical expertise necessary to exercise their powers effectively.

Bill S-4 was introduced by the government as this report was being written. Upon its introduction, we noted that it includes breach notification, enforceable agreements with companies and stronger compliance incentives while providing greater discretion to publicly share more information with Canadians about our investigations.

On June 4, 2014 we presented our views and submission to the Senate Transport and Communications Committee.

Feature: Notice and Consent

Transparency: Key to consumer trust online

The dawn of the digital marketplace has transformed commerce in more ways than one.

Today’s consumers have the ability to browse infinite brands and boutiques with their fingertips, all without having to leave their homes. But somewhere along the way to this new reality, consumers ceased being simply purchasers, but became products themselves.

Many online services are fiscally free with personal information taking the form of the real currency. In other words, cost-free content comes at a price of personal data rather than dollars. And, often as not, it’s the online enterprise collecting the data, rather than the customer relinquishing it, who determines what happens next.

At the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, we recognize this evolution within the marketplace and want everyone to understand the new reality.

We want businesses to be clear about what they're doing with people's personal information, so that consumers can make informed choices in both their purchases and online activities.

Consider, for instance, that the traditional two-way relationship between buyer and seller has become complicated in the online marketplace by other interests, including advertisers and a myriad of other collectors of personal data.

And that personal data includes so much more than the name and address you knowingly submit; it now encompasses data about your location, activities and preferences that flow automatically from your electronic devices, often without your knowledge.

Transparency and accountability

PIPEDA Principle 8

Openness

An organization shall make readily available to individuals specific information about its policies and practices relating to the management of personal information.

That is why we encourage all businesses, especially those operating online, to be upfront about their privacy practices and ensure they are conveyed effectively. Websites should explain clearly what personal information is collected, how it is used, that it is appropriately safeguarded, whether it is disclosed to third parties and for what purpose. The explanation should be conspicuous, accessible, clear and useful. It should, moreover, be reinforced by the designation of a contact within the organization to whom customers can bring questions and concerns.

Without such transparency, customers cannot provide the meaningful consent necessary for a business to collect their personal information. Transparency helps make businesses accountable and breeds trust on the part of consumers. More and more, it will become integral to the smooth functioning of the online market.

But are we there yet? The answer is an emphatic "no".

Following investigation, Apple clarifies aspects of data collection for consumers

In a case tied tightly to online privacy transparency, an individual alleged that Apple Canada should not have required him to supply certain data during the process of creating his Apple-specific identifier, known as an Apple ID, which was needed to download a free application from the Apple website. The process called for payment information, such as a credit card number and a date of birth.

Upon investigation we concluded that Apple had a legitimate right to use birthdates to help authenticate the identities of several million Canadian customers. However, we noted that the company's privacy policy did not fully explain this practice. Apple agreed to update its policy. In anticipation of this clarification, we deemed this aspect of the complaint to be well-founded and conditionally resolved.

With respect to the collection of financial information, Apple stated that its website's support section contained instructions for downloading free apps without providing payment information. According to Apple, using the search term "credit card", one of the search results would enable users to learn that the payment card requirement could be bypassed by following a specific alternative process.

We reviewed hundreds of comments from frustrated users in an Apple open forum, and conducted our own technical analysis. We concluded that the workaround for the free apps was not evident, and that Apple did not make its policies and practices on the collection of credit card data clear to users at the relevant time—namely when a user registered for an ID.

We were concerned that Apple’s practices could result in the over-collection of sensitive payment information.

We deemed this aspect of the complaint to be well founded, and recommended that Apple clearly communicate to users that a form of payment is not required when registering for an Apple ID for the purpose of downloading a free application. We recommended that Apple could achieve this by adding the option of proceeding without the need to supply payment information at every point of registration. In response to our final report of findings, Apple agreed to our recommendation. In the end, we were very pleased with Apple’s commitment to users in agreeing to address the issues stemming from our investigation. Changes are to come into effect in the fall.

Sweeping changes

When it comes to transparency, Canadian commercial websites are, unfortunately, a mixed bag. We know this from the first-ever Internet Privacy Sweep, a ground-breaking initiative that our Office developed and led in 2013. In concert with 18 other data-protection authorities and the Global Privacy Enforcement Network, we scanned 2,276 websites and mobile apps during a single week in May.

Approaching each website like any other consumer, we searched for a formal policy or statement about the organization's privacy practices. Were such privacy-related communications prominent and easy to find? Where we found them, we assessed whether information was useful, such that ordinary customers would understand the information in a meaningful way. And, if individuals had questions or concerns, were they directed to a specific contact within the organization?

In Canada we examined 326 websites of companies in fields as diverse as trip planning, fast food, pharmaceuticals, insurance, furniture, communications and paternity testing. We published the results of our sweep in August, and they were not uniformly encouraging.

Indeed, we spotted problems on nearly half of all websites examined. For instance, nearly one in 10 had no discernable privacy policy at all. One in eight concealed their privacy-related information so well that they became trophies for only the most determined hunters.

Where policies could be found, they often were so succinct that they didn't provide meaningful information about privacy practices. A few were as petite as a tweet.

Others, by contrast, went overboard with rambling dissertations that would bore a contracts lawyer. Indeed, a familiarity with statute law was handy for several privacy policies that offered nothing more illuminating than verbatim excerpts from PIPEDA.

Particularly vexing were the dead ends. Every fifth site did not include any contact information. One website invited customers to e-mail their questions or concerns, then baffled them by furnishing no contact e-mail address.

Other jurisdictions that participated in the sweep made similar observations, although they reported that things were even worse among mobile apps.

Cause for optimism

Still, things were not all gloomy; we were pleased to report some good news as well. We certainly did find privacy policies that were clear, accessible and user-friendly. One company went beyond the call of duty by offering a mechanism for the anonymous reporting of privacy breaches.

Canada, it turns out, also fared better than the global average. For instance, 21 percent of all sites and apps swept around the world had no privacy statement-more than twice the failure rate we discovered in Canada.

Showing Resolve

Building on the success of the Internet Privacy Sweep, our Office teamed up with the UK Information Commissioner's Office to propose a Resolution on Openness of Personal Data Practices at the annual meeting of the International Conference of Data Protection Commissioners in Warsaw in September 2013. The resolution was adopted; 90 privacy-enforcement authorities around the world will now focus on encouraging organizations to be more transparent in their privacy practices.

The publicity garnered by the initiative generated a flurry of voluntary activity, as organizations made their privacy policies clearer and therefore more useful for individuals. On top of that, we leveraged lessons gleaned from Sweep results to promote best practices by publishing Ten Tips for a Better Online Privacy Policy and Improved Privacy Practice Transparency and we are planning to follow up in 2014 with a formal guidance document for businesses.

Where we identified specific concerns that were not resolved in the wake of the publicity surrounding the Sweep, we issued compliance letters. This prompted 40 organizations to significantly boost the transparency of their privacy communications. Best of all, we achieved these ends without the need for a single, resource-intensive complaint investigation.

Taking action

But the transparency story doesn't end there, because even the most perfect privacy policy is a passive thing. It only becomes useful when a consumer puts it to use.

And so we encourage people who deal with online businesses to routinely check out their privacy policies and other privacy-related information, and to follow up with the company if something is unsatisfactory or unclear. This sort of give-and-take reminds enterprises that their customers value privacy. At the same time, it gives customers another important tool with which to make informed choices about their online transactions.

Moving forward, we're hoping for further refinements in this important relationship between customers and businesses. For example, and especially in an age when more of us use online services on the go and our screens are growing smaller, it's high time to rethink the practice of presenting customers with long, dense, legalistic explanations of how their personal information might be gathered, used and disclosed to others, then asking them to accept the terms for the remainder of the interaction.

Rather, we recommend companies use a range of strategies to enhance the prominence, relevance and readability of the privacy information, so that the consent the customer provides on the basis of this information is truly meaningful.

For instance, notices about the use of personal information should be provided at material decision points including the exact point when the customer is asked to provide it (e.g., registration and/or payment), making the option to carry on or quit more real.

In other words, as technology evolves, so should the conveyance of privacy information.

Unfortunate events

As we all know, even the best-made intentions and best-laid plans are sometimes derailed by accidents and unforeseen events. And so it is, too, with online privacy. Privacy policies and protections can sometimes not immediately stand-up to innovative and emerging cyberthreats which call for the emergence of equally innovative safeguards.

Put another way, a significant threat to the integrity of personal information stems from the limitations and vulnerabilities of technology. Despite an organization's best efforts, the data it collects may be compromised by hackers, swindlers and thieves. In addition to such deliberate breaches, data may simply be lost on a misplaced thumb drive due to failing to follow proper safe handling procedures.

There's also the problem of web leakage, in which the personal information of a site's registered users seeps through to third parties such as advertisers. Our Office researched the phenomenon by testing 25 websites. We reported in 2012 that 11 of the sites were leaking information such as names and e-mail addresses.

Last year we followed up to see whether efforts had been made to halt the flow. We were pleased to report that several organizations had taken steps to arrest the unintentional or unnecessary disclosures of personal information. Another site, which shared information with third-party service providers in order to manage its website, agreed to update its privacy policy to make this practice clear to consumers.

Trust and loyalty

Transparency in an organization's approach to privacy protection is good for business.

First and foremost, it makes the enterprise more accountable to its customers. An accountable organization will ensure that its staff adopts good and transparent privacy practices, which in turn reduce the risk of costly, sometimes catastrophic, privacy breaches.

With time and experience, customers will also begin to favour the companies they trust the most. And trust flows to organizations that recognize their customers' privacy rights, and are able to protect them with meaningful policies that are clearly articulated.

Despite the many changes brought forth by the digital marketplace, trust remains a timeless and true commodity. While it may not be clear that “the customer is always right”, surely no business ever wants to be seen as making its clientele feel wronged.

And in today’s data-driven world if people aren’t satisfied that their personal information is being treated with care and respect, they’ll simply take their business elsewhere in the vast online universe.

Investigation Statistics

| Sector Category | Number | Proportion of all complaints accepted |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodations | 12 | 3% |

| Entertainment | 3 | 1% |

| Financial | 65 | 15% |

| Insurance | 18 | 4% |

| Internet | 19 | 4% |

| Other Sectors | 16 | 4% |

| Professionals | 9 | 2% |

| Sales/Retail | 28 | 7% |

| Services | 28 | 6% |

| Telecommunications | 212 | 50% |

| Transportation | 16 | 4% |

| Total | 426 | 100% |

| Complaint Type | Number | Proportion of all complaints accepted |

|---|---|---|

| Access | 54 | 13% |

| Accountability | 2 | 0% |

| Accuracy | 3 | 1% |

| Appropriate purposes | 173 | 41% |

| Collection | 23 | 5% |

| Consent | 38 | 9% |

| Correction/Notation | 9 | 2% |

| Identifying Purposes | 1 | 0% |

| Retention | 2 | 0% |

| Safeguards | 30 | 7% |

| Use and Disclosure | 91 | 22% |

| Total | 426 | 100% |

| Sector category | Dispositions | Total dispositions minus ER | Total - all dispositions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early resolution (ER) | Declined | Discontinued (under 12.2) | No Jurisdiction | Withdrawn | Settled | Not well-founded | Well-founded | Well-founded resolved | Well-founded conditionally resolved | |||

| Telecommunications | 28 | 166 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 184 | 212 | |

| Financial | 27 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 13 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 40 |

67 |

|

| Internet | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 15 |

29 |

|

| Services | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

23 |

|

| Sales/Retail | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

23 |

| Other Sectors | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 12 |

18 |

|

| Accommodations | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

16 |

|

| Transportation | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

11 |

|

| Insurance | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

10 |

|

| Health | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

6 |

|

| Professionals | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

6 |

|

| Entertainment | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

3 |

|

| Total | 133 | 1 | 170 | 2 | 31 | 20 | 24 | 8 | 32 | 3 | 291 |

424 |

| Complaint Type | Dispositions | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early resolution | Discontinued (under 12.2) | Declined | No Jurisdiction | Withdrawn | Settled | Not well-founded | Well-founded | Well-founded resolved | Well-founded conditionally resolved | ||

| Appropriate purposes | 1 | 165 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 172 | |

| Use and Disclosure | 45 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 77 | |

| Access | 33 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 63 |

| Consent | 20 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 33 | |

| Collection | 9 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 23 | |

| Safeguards | 9 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 19 | |

| Correction/Notation | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 13 | |

| Accuracy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 11 | |

| Accountability | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Retention | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | |

| Challenging Compliance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Identifying Purposes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 133 | 170Footnote 4 | 1 | 2 | 31 | 20 | 24 | 8 | 32 | 3 | 424 |

| Complaint Type | Early Resolution (ER) | All Other Resolutions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Average Treatment Time in Months | Number | Average Treatment Time in Months | |

| Access | 33 | 3.0 | 30 | 14.1 |

| Accountability | 4 | 2.6 | 1 | 5.2 |

| Accuracy | 1 | 1.0 | 10 | 14.5 |

| Appropriate purposes | 1 | 2.8 | 171 | 2.0 |

| Challenging Compliance | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 18.3 |

| Collection | 9 | 2.5 | 14 | 16.4 |

| Consent | 20 | 1.8 | 13 | 13.6 |

| Correction/Notation | 9 | 1.6 | 4 | 12.6 |

| Identifying Purposes | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Retention | 1 | 4.7 | 4 | 16.3 |

| Safeguards | 9 | 2.3 | 10 | 8.4 |

| Use and Disclosure | 45 | 2.1 | 32 | 12.0 |

| Total | 133 | 2.3 | 291 | 6.7 |

| Disposition | Number | Average Treatment Time in Months |

|---|---|---|

| ER-Resolved | 133 | 2.3 |

| Settled | 20 | 6.7 |

| Discontinued (under 12.2) | 170 | 2.1 |

| Withdrawn | 31 | 8.8 |

| No Jurisdiction | 2 | 4.4 |

| Not well-founded | 24 | 16.5 |

| Well-founded conditionally resolved | 3 | 14.7 |

| Well-founded resolved | 32 | 18.3 |

| Well-founded | 8 | 19.3 |

| Declined to investigate | 1 | 2.8 |

| Total cases | 424 | |

| Overall weighted average | 5.3 |

| Sector | Incident type | Total incidents per sector | Proportion of all incidents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accidental disclosure | Loss | Theft or unauthorized access | |||

| Accommodations | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1% |

| Entertainment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1% |

| Financial | 5 | 2 | 8 | 15 | 25% |

| Health | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1% |

| Insurance | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 14% |

| Internet | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 10% |

| Other Sectors | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 14% |

| Professionals | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7% |

| Sales/Retail | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 10% |

| Services | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 10% |

| Telecommunications | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7% |

| Total | 20 | 7 | 33 | 60 | 100% |

Appendix 1 — Definitions of Complaint Types under PIPEDA

Complaints received by the OPC are categorized according to the principles and provisions of PIPEDA that are alleged to have been contravened:

Access. An individual has been denied access to his or her personal information by an organization, or has not received all the personal information, either because some documents or information are missing or because the organization has applied exemptions to withhold information.

Accountability. An organization has failed to exercise responsibility for personal information in its possession or custody, or has failed to identify an individual responsible for overseeing its compliance with the Act.

Accuracy. An organization has failed to ensure that the personal information it uses is accurate, complete, and up-to-date.

Challenging compliance. An organization has failed to put procedures or policies in place that allow an individual to challenge its compliance with the Act, or has failed to follow its own procedures and policies.

Collection. An organization has collected personal information that is not necessary, or has collected it by unfair or unlawful means.

Consent. An organization has collected, used or disclosed personal information without meaningful consent, or has made the provision of a good or service conditional on individuals consenting to an unreasonable collection, use, or disclosure.

Correction/Notation. The organization has failed to correct personal information as requested by an individual, or, where it disagrees with the requested correction, has not placed a notation on the information indicating the substance of the disagreement.

Fee. An organization has required more than a minimal fee for providing individuals with access to their personal information.

Openness. An organization has failed to make readily available to individuals specific information about its policies and practices relating to the management of personal information.

Retention. Personal information is retained longer than necessary for the fulfillment of the purposes that an organization stated when it collected the information, or, if it has been used to make a decision about an individual, has not been retained long enough to allow the individual access to the information.

Safeguards. An organization has failed to protect personal information with appropriate security safeguards.

Time limits. An organization has failed to provide an individual with access to his or her personal information within the time limits set out in the Act.

Use and disclosure. Personal information is used or disclosed for purposes other than those for which it was collected, without the consent of the individual, and the use or disclosure without consent is not one of the permitted exceptions in the Act.

Appendix 2 — Definitions of Findings and Other Dispositions

At the beginning of 2012, our Office altered some of the definitions of findings and dispositions so that they would better convey the outcomes of our investigations under PIPEDA. These goal of the new dispositions was also to better reflect the responsibilities of organizations to demonstrate accountability under the Act.

The definitions below explain what each disposition means.

Not well founded: The investigation uncovered no or insufficient evidence to conclude that an organization contravened PIPEDA.

Well founded and conditionally resolved: The Commissioner determined that an organization contravened a provision of PIPEDA. The organization committed to implementing the recommendations made by the Commissioner and demonstrating their implementation within the time frame specified.

Well founded and resolved: The Commissioner determined that an organization contravened a provision of PIPEDA. The organization demonstrated it had taken satisfactory corrective action to remedy the situation, either proactively or in response to recommendations made by the Commissioner, by the time the finding was issued.

Well founded: The Commissioner determined that an organization contravened a provision of PIPEDA.

Settled: The OPC helped negotiate a solution that satisfied all involved parties during the course of the investigation. The Commissioner does not issue a report.

Discontinued: The investigation was discontinued before the allegations were fully investigated. An investigation may be discontinued at the Commissioner’s discretion for the reasons set out in subsection 12.2(1) of PIPEDA, as a result of a request by the complainant, or where the complaint has been abandoned.

Declined to Investigate: The Commissioner declined to commence an investigation in respect of a complaint because the Commissioner was of the view that the complainant ought first to exhaust grievance or review procedures otherwise reasonably available; the complaint could be more appropriately dealt with by means of another procedure provided for under the laws of Canada or of a province; or, the complaint was not filed within a reasonable period after the day on which the subject matter of the complaint arose, as set out in subsection 12(1) of PIPEDA.

No jurisdiction: Based on the preliminary information gathered, it was determined that PIPEDA did not apply to the organization or activity that was the subject of the complaint. The Commissioner does not issue a report.

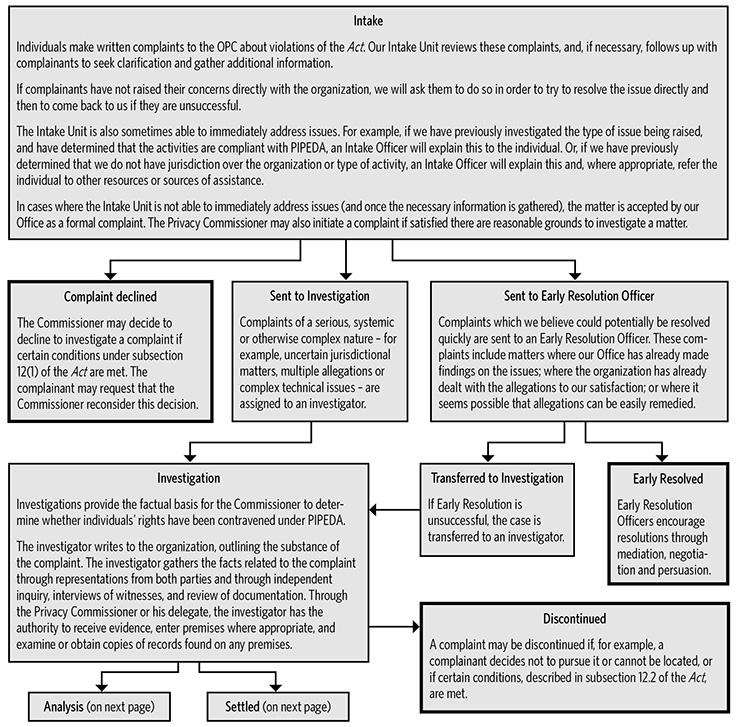

Appendix 3 — Investigation Process

Text version

Investigation Process

Intake

Individuals make written complaints to the OPC about violations of the Act. Our Intake Unit reviews these complaints, and, if necessary, follows up with complainants to seek clarification and gather additional information.

If complainants have not raised their concerns directly with the organization, we will ask them to do so in order to try to resolve the issue directly and then to come back to us if they are unsuccessful.

The Intake Unit is also sometimes able to immediately address issues. For example, if we have previously investigated the type of issue being raised, and have determined that the activities are compliant with PIPEDA, an Intake Officer will explain this to the individual. Or, if we have previously determined that we do not have jurisdiction over the organization or type of activity, an Intake Officer will explain this and, where appropriate, refer the individual to other resources or sources of assistance.

In cases where the Intake Unit is not able to immediately address issues (and once the necessary information is gathered), the matter is accepted by our Office as a formal complaint. The Privacy Commissioner may also initiate a complaint if satisfied there are reasonable grounds to investigate a matter.- Complaint declined

The Commissioner may decide to decline to investigate a complaint if certain conditions under subsection 12(1) of the Act are met. The complainant may request that the Commissioner reconsider this decision. - Sent to Investigation

Complaints of a serious, systemic or otherwise complex nature – for example, uncertain jurisdictional matters, multiple allegations or complex technical issues – are assigned to an investigator.

- Investigation

Investigations provide the factual basis for the Commissioner to determine whether individuals’ rights have been contravened under PIPEDA.

The investigator writes to the organization, outlining the substance of the complaint. The investigator gathers the facts related to the complaint through representations from both parties and through independent inquiry, interviews of witnesses, and review of documentation. Through the Privacy Commissioner or his delegate, the investigator has the authority to receive evidence, enter premises where appropriate, and examine or obtain copies of records found on any premises.

- Analysis

The investigator analyses the facts and prepares recommendations to the Privacy Commissioner or his delegate.

Analysis will include internal consultations with, for example, the OPC’s Legal Services, Research, or Policy Branches, as appropriate.

The investigator will contact the parties and review the facts gathered during the course of the investigation. The investigator will also advise the parties of his or her recommendations, based on the facts, to the Privacy Commissioner or his delegate. At this point, the parties may make further representations.

- No Jurisdiction

The OPC determines that PIPEDA does not apply to the organization or activities being complained about.

- Findings

The Privacy Commissioner or his delegate reviews the file and assesses the report. The Privacy Commissioner or his delegate (not the investigator) decides what the appropriate outcome should be and whether recommendations to the organization are warranted.

- Preliminary Report

If the results of the investigation indicate that there likely has been a contravention of PIPEDA, the Privacy Commissioner or his delegate recommends to the organization how to remedy the matter, and asks the organization to indicate within a set time period how it will implement the recommendation.

- Final Report and Letters of Findings

The Privacy Commissioner or his delegate sends letters of findings to the parties. The letters outline the basis of the complaint, the relevant findings of fact, the analysis, and the response of the organization to any recommendations made in the preliminary report.

(The possible findings are described in the Definitions Section of this Appendix.)

In the letter of findings, the Privacy Commissioner or his delegate informs the complainant of his or her rights of recourse to the Federal Court.

- Where recommendations have been made to an organization, but have not yet been implemented, the OPC will ask the organization to keep us informed, on a predetermined schedule after the investigation, so that we can assess whether corrective action has been taken.

- The complainant or the Privacy Commissioner may choose to apply to the Federal Court for a hearing of the matter. The Federal Court has the power to order the organization to correct its practices. The Court can award damages to a complainant, including damages for humiliation. There is no ceiling on the amount of damages.

- No Jurisdiction

- Settled

The OPC seeks to resolve complaints and to prevent contraventions from recurring. The OPC helps negotiate a solution that satisfies all involved parties during the course of the investigation. The investigator assists in this process.

- Discontinued

A complaint may be discontinued if, for example, a complainant decides not to pursue it or cannot be located, or if certain conditions, described in subsection 12.2 of the Act, are met.

- Analysis

- Investigation

- Sent to Early Resolution Officer

Complaints which we believe could potentially be resolved quickly are sent to an Early Resolution Officer. These complaints include matters where our Office has already made findings on the issues; where the organization has already dealt with the allegations to our satisfaction; or where it seems possible that allegations can be easily remedied.

- Transferred to Investigation

If Early Resolution is unsuccessful, the case is transferred to an investigator.

- Early Resolved

Early Resolution Officers encourage resolutions through mediation, negotiation and persuasion.

- Transferred to Investigation

Alternate versions

- PDF (2.6 MB) Not tested for accessibility

- Date modified: