Privacy Act Annual Report to Parliament 2013-14

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Transparency and Privacy in the Digital Age

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

30 Victoria Street – 1st Floor

Gatineau, QC

K1A 1H3

(819) 994-5444, 1-800-282-1376

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2014

Cat. No. IP50-2014E-PDF

1913-7559

This publication is also available on our website at www.priv.gc.ca

Follow us on Twitter: @PrivacyPrivee

October 2014

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

October 2014

The Honourable Andrew Scheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

1. Commissioner’s Message

The right to privacy is one of our fundamental rights and freedoms as Canadians. And amidst ever-evolving technological capacity to both collect and analyse personal information, this needs to be protected with continuing commitment and care.

I was appointed Privacy Commissioner after the end of the 2013-2014 period covered by this annual report on the Privacy Act. And while I was not at the organization’s helm, the year gone by shows that the profile of privacy has gained prominence and for good reason. Never before in human history has personal information been as available as it now is and consequently never before has protecting personal information been as important.

Against this backdrop, the period under review was a time of mounting privacy concerns.

The year in particular was marked by the continuation of a long-running debate in Canada about lawful access to subscriber information along with a series of ongoing revelations about state surveillance activities that had impact globally as well as within our borders.

As another indicator, statistics show there was a continued rise in the number of complaints. Also continuing are complaints from a large number of individuals that arise from a single event. For example, the Office is currently investigating 339 complaints over a mass mailing by Health Canada which allegedly exposed the names and mailing addresses of some 40,000 people involved in the marijuana medical access program.

In a year where perhaps unprecedented attention was paid to public sector data breaches, the 228 separate data breaches voluntarily reported across the federal government in 2013-2014 were more than double those from the previous fiscal year. This marked the third consecutive year where a record high was reached for such reports. Accidental disclosure was provided as the reason indicated by reporting organizations behind more than two-thirds of the breaches.

Important Lessons Learned

Much of the attention about public sector data breaches was generated by the loss of a hard drive containing information about more than 500,000 student loan recipients from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC, then known as Human Resources and Skills Development Canada – HRSDC). A March 2014 Special Report to Parliament on the incident underscored the lesson that once organizations develop formal privacy and security policies, so too they must be put into practice and monitored regularly.

The OPC produced tip sheets for public servants on how to protect against data breaches when using external hard drives and other portable storage devices (see section 5). In addition, our Office is currently auditing how well personal information on such portable storage devices is being protected in 17 selected government agencies and departments.

As noted in previous years, because data breach reporting to the OPC has been voluntary, the Office could never say categorically that the number of incidents had really risen from one year to the next. The increase might simply have been the result of more diligent reporting. From now on, however, such uncertainty should be reduced, thanks to a revised Directive on Privacy Practices from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS).

The Directive makes mandatory the reporting of any “material” data breach to both the TBS and the OPC. The OPC worked with TBS to define what constitutes a material breach and also created a web-based form housed on the OPC website for federal institutions to report such breaches.

This work followed a number of breaches that highlighted the need for increased vigilance in safeguarding personal information held by organizations. For example, this year’s report includes a look at the Office’s investigation of ESDC and Justice Canada concerning a lost USB key. The portable device with the personal information of 5,045 people appealing their disability entitlements under the Canada Pension Plan disappeared from an office at ESDC where it was being used by a Justice lawyer. After an investigation, the resulting OPC recommendations echoed those made in the special report following the student loan hard drive loss.

Invasive Security Screening

While data breaches remained a key focus of 2013-2014, a key trend noted in Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) reviewed during the past year was that of some government institutions developing more invasive security screening techniques going beyond the existing security requirements of the federal government. In several cases, these enhanced screening standards involved collecting personal data from social media and other open sources.

For example, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) submitted a PIA for its “Reliability Status+” personnel security screening standard, which proposed a number of new, more intrusive screening measures including open social media content, law enforcement records checks, and a reliability questionnaire. After consulting with our Office, the Agency amended its program considerably (for more on this, see section 5).

In addition, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) implemented its High Integrity Personnel Security Screening Standard (focused on in last year’s Annual Report), which includes an “integrity interview” that collects a significant amount of personal information.

RCMP Review

One of the liveliest and most important public discussions around privacy in Canada for many years has been the lawful access debate. Seeking to advance it, our Office launched a review to determine whether the RCMP had appropriate controls in place to ensure its collection of subscriber information from companies without a warrant was in compliance with the Privacy Act.

In the end, we were disappointed to find that limitations in how the RCMP recorded this information meant we were unable to assess whether such controls were in place. It was impossible to determine how often the RCMP collected subscriber data without a warrant. Nor could we assess whether such requests were justified. The review is included in this report in section 4.

State Surveillance

Over-shadowing all of the issues already described has been a much higher profile for the ongoing challenge in Canada and other democratic states about conserving the right of privacy of individuals in a digital era while also pursuing effective national security. Public concern has been heightened by revelations about state surveillance activities, especially among the so-called “Five Eyes,” which is an intelligence alliance comprising Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S.

The fallout from the revelations is examined in some additional detail in our Feature, found in section 3. In particular, we consider their impact on public expectations for greater transparency from security agencies about how they operate and use personal information within reason, given the sensitivity of their activities.

An OPC Special Report to Parliament in January 2014 entitled Checks and Controls: Reinforcing Privacy Protection and Oversight for the Canadian Intelligence Community in an Era of Cyber-Surveillance examined many of these issues. Introducing 10 detailed recommendations, the report stated:

The aim of renewal in this area should be to protect privacy in a complex threat environment; oversee collection so that it is reasonable, proportionate and minimally intrusive; ensure appropriate retention and access controls (among both public and private sectors); ensure accuracy of analysis; and control the scope of information requests and disclosures through specific safeguards, agreements and caveats.

Looking Ahead

In addition to issues involving privacy and national security, the OPC will also be closely watching developments on several other federal government privacy fronts. We have concerns about the potential adverse privacy impact of Bill C-13, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act, which were detailed in my June 2014 appearance before the House of Commons Justice and Human Rights Committee (see section 5).

Just days afterwards, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that there is indeed a reasonable expectation of privacy in Internet subscriber information (R. v. Spencer). The Court agreed that this information could, in many cases, be the key to unlocking sensitive details about a user’s online activities and is therefore worthy of constitutional protection.

Our Office will be closely monitoring the progress of C-13 to see what impact our recommendations and the Supreme Court ruling will have on the government’s approach. We will also be tracking data breaches in government departments and agencies to assess the impact of the new mandatory reporting rules.

Continuing Emphasis On The Border

In the coming year, the Canada-U.S. border will remain one of our key points of focus. The 2011 Beyond the Border Declaration and 2012 Perimeter Security Action Plan, committed the Government of Canada to a reinforced vision of continental security, while also making it easier for people and goods to cross the border.

Under the Action Plan, the continued roll-out of the entry/exit program means that the record of someone entering the U.S. from Canada by land will automatically become a record of their exit from our country. Until the initial phases of this program, which has already started collecting information about the exits of foreign nationals and temporary residents, Canada had previously not collected such information.

The CBSA justified the program’s first phases by indicating it was necessary for immigration enforcement. In future phases, the program is planned to collect information about all Canadian and U.S. citizens crossing the border by any means. In its final phase, it will also capture exit information for all individuals leaving Canada by air to any destination. As the lead responsible for this program, CBSA now also proposes sharing exit records much more widely across government so they may potentially be used to ensure the integrity of social benefit programs, for taxation and general law enforcement and intelligence purposes.

As the details of these programs unfold, our Office expects the CBSA and any other department involved to submit PIAs for such proposed new uses of the personal information with evidence that any potential adverse impacts on privacy are being addressed accordingly (see section 5). We will also urge the government to be fully transparent about any intended uses of these records, including how they could be combined with other collected data.

In Closing

Finally, as noted earlier, I was not Commissioner during the 2013-2014 period, and I wish to recognize the efforts and achievements of my predecessor, Jennifer Stoddart, who served as Commissioner for a decade rich with rising challenge and achievement. I also wish to recognize Chantal Bernier who acted as Commissioner upon Ms. Stoddart’s departure and served as Assistant Commissioner from 2008 to 2013.

Under Ms. Stoddart’s leadership, the Office had undertaken an exercise to identify strategic priority areas to guide its proactive work, which served the organization well for several years.

Even before I joined the Office, there was a plan in place to take another look and identify strategic priorities for the next few years.

We are currently embarking upon a priority-setting exercise to help ensure that we focus on the privacy issues that matter most to Canadians. As part of this initiative, we will be meeting with various stakeholders and groups to seek their input.

As I continue the first year of my term as Commissioner, I look forward to meeting Canadians’ privacy priorities in an increasingly challenging environment. And thankfully, I do so with the support of a talented and knowledgeable team dedicated to protecting Canadians’ privacy rights.

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

2. Privacy by the Numbers – 2013-2014

| Information requests received relating to PA | 2,147 |

|---|---|

| Complaints accepted (access, time limits, privacy) | 1,777 |

| Closed through early resolution investigations (access, time limits, privacy) | 345 |

| Closed through standard investigations (access, time limits, privacy) | 1,740 |

| PIA reviews reviewed as high risk PIAs reviewed as lower risk |

65 36 |

| Public sector audits tabled | 2 |

| Public interest disclosures by federal organizations under section 8(2)(m) | 296 |

| Legislation affecting federal public sector reviewed for privacy implications | 8 |

| Public sector policies or initiatives reviewed for privacy implications | 35 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on public sector matters | 5 |

| Formal briefs submitted | 4 |

| Other interactions with parliamentarians or staff (for example, correspondence with MPs or Senators) | 28 |

| Speeches and presentations delivered | 107 |

| Visits to main Office website | 2,080,099 |

| Visits to Office blogs and YouTube channel | Blog visits – 623,163 YouTube visits – 21,842 |

| Tweets sent | 235 |

| Twitter followers as of March 31, 2014 | 7,636 |

| Publications distributed | 5,709 |

| News releases and announcements issued | 25 |

3. Feature: From surveillance revelations to a seminal Supreme Court of Canada ruling: 12 months of privacy at centre stage

Here we examine what was certainly the biggest privacy story of the past year in Canada, and focus on the genesis of one of the year’s biggest stories internationally – of any kind, not just about privacy.

From June 2013 to June 2014, terms like “metadata” and “Five Eyes,” previously found almost exclusively in blogs read by privacy technologists and policy experts, were vaulted into mainstream news headlines and leads. And while revelations about state surveillance provided an unprecedented view into the operations of intelligence agencies, they also raised and continue to raise important questions calling for greater transparency.

In all, June 2013 through June 2014 was a 12 month span that began with reports that seemed to suggest privacy might be hopelessly besieged and ended with the Supreme Court of Canada recognizing that a reasonable expectation of privacy applies to subscriber information like IP addresses. And there were many twists and turns in between.

Through it all, the importance Canadians place upon privacy protection proved unequivocal. At the same time however, no one should disregard the priority Canadians place upon the government protecting their security and safety.

In the end, it’s not a question of “either, or” – it is possible to have both. And Canadians want greater transparency to see that these objectives are being sufficiently respected.

Looking back and assessing the impact

In June 2013, highly technical, classified details began emerging from documents supplied to news media outlets by Edward Snowden, a former contractor with the National Security Agency (NSA), the American signals intelligence organization.

In the following months, more releases exposed covert operations by the NSA to monitor the private communications of world leaders. They also revealed a vast capability to capture, store and analyze metadata on private communications and internet transactions – all with an aim to detailing where and when conversations or interactions took place between individuals anywhere in the world.

The revelations also uncloaked specific actions taken by the four other “Five Eyes” member countries – Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the U.K. – whose intelligence agencies collaborate and share information with their American counterparts.

For Canadians, details from documents were reported to reveal specific operations carried out by our domestic signals intelligence agency, the Communication Security Establishment Canada (CSEC). These ranged from monitoring world leaders’ communications at the G20 Summit in Toronto to tracking individuals from an unnamed Canadian airport in 2009.

In the wake of revelations, media coverage and Parliamentary debate were intense and ongoing. During the second session of the 41st Parliament (October 16, 2013 to June 19, 2014), parliamentarians raised more than 50 questions about CSEC in the House of Commons and the Senate.

Focusing on intelligence activity oversight

As Parliamentary debate and headlines roiled, the intricacies of such surveillance came under scrutiny. One question, however, towered above the rest, the age-old “who watches the watchers?” And further, “how were parliamentarians and the Canadians they serve being informed about how this oversight is taking place and getting results?”

The challenge of intelligence activity oversight turned a spotlight on the work of CSEC’s oversight body, the Office of the CSE Commissioner (OCSEC), and also on the Security Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC), which oversees the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS).

In early December, the Senate Committee on National Security and Defence convened hearings about intelligence activity oversight, hearing initially from our Office, OCSEC and SIRC, and later from the heads of CSEC and CSIS, and the National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister.

On December 9, 2013, Interim Privacy Commissioner Chantal Bernier testified about the privacy implications of information-sharing among Canada’s intelligence agencies. She reminded the Committee that the heads of both OCSEC and SIRC had pointed out publicly their inability under the law to jointly review large-scale, ongoing information-sharing between members of the intelligence community.

This gap arose partly because, contrary to the agencies they oversee, these two oversight bodies face fairly rigid statutory and security limits on how they can work together.

In January 2014, a report by our Office was tabled in Parliament entitled, Checks and Controls: Reinforcing Privacy Protection and Oversight for the Canadian Intelligence Community in an Era of Cyber-Surveillance. Its general objective was to inform and encourage a greater public discussion of issues surrounding intelligence activity oversight and transparency. Among its recommendations was that the government address previous concerns expressed by oversight bodies with respect to their ability to conduct joint reviews.

The Senate Committee is expected to conclude its hearings and issue a report later in 2014.

Revealing the private-to-public-sector pathway

While the revelations about state surveillance gave ordinary citizens unprecedented glimpses into the largely opaque world of intelligence activities, they also brought to light something that hit closer to home for most. On June 5, 2013, these particular revelations began with a report about telecommunications service provider Verizon being legally compelled by the NSA to provide duplicates each day of all its subscribers’ call logs, thus opening the public debate on metadata.

In the same week, news emerged about the NSA’s PRISM program through documents which detailed the Agency’s capacity to tap into data from major online service providers, including many where Canadians held email and social networking accounts.

Days later, in Canada, news surfaced about CSEC’s own metadata program under which, the Globe and Mail reported, “CSEC ‘incidentally’ intercepts Canadian communications, but takes pain to purge or ‘anonymize’ such data after it is obtained.”

These media reports added to the discussion about online privacy. In the months that followed, our Office commissioned an analysis to explore the legal status of metadata.

While security agencies on both sides of the 49th parallel maintain that collecting and analysing metadata en masse is not the same as scanning an individual’s email or listening in on a conversation, at a minimum this log data details what time a communication was made, from what location and to whom. Collecting such data over a long period of time can begin to paint detailed portraits of the activities and social lives of individuals. For this reason, our analysis concludes that “[i]n many cases, courts have recognized that metadata can reveal much about an individual and it deserves privacy protection, all the while recognizing that context matters.”

A metadata primer

In simple terms, metadata is data that provides information about other data. However, as an OPC technical and legal overview makes clear, there’s much more to metadata than meets the eye.

Every time you make an electronic communication be it a phone call or an email, metadata is produced. For instance the simple act of sending an email can generate a dozen different pieces of metadata, ranging from the names and email addresses of the sender and the recipient to the message subject, priority and status.

The sender’s IP address is also exposed and when this is linked to other basic telecommunications subscriber information, that can reveal someone’s interests, ideological leanings, the people they associate with and where they travel. Indeed, as the OPC overview emphasizes, metadata can sometimes be more revealing than the actual content of a communication.

Of further concern is that metadata can be a great destroyer of anonymity. For example, using a metadata search engine, a newspaper reporter in Vancouver was able to compile a detailed profile of a 16-year-old female starting with only a randomly selected, geo-tagged tweet.

The OPC overview also chronicles a rapid evolution in how the courts have defined metadata, culminating in the judicial view that in many cases metadata may permit the drawing of inferences about an individual’s conduct or activities. This potential privacy sensitivity and metadata’s ubiquitous nature means it must be handled with care by both the private and public sectors.

Quantifying warrantless disclosures

In April 2014, a few months after the reports of metadata collection by the NSA and CSEC, privacy concerns were stoked further by the disclosure of how often Canadian telecommunications service providers turned over subscriber information to authorities, on simple request without a warrant. Aggregate data from telecom companies supplied to the OPC by a law firm acting on behalf of nine telecommunications carriers indicated that 1.2 million requests had been filed by investigators in 2011, an average of more than 3,200 a day.

In addition, our Office launched a review of the RCMP’s warrantless access requests during the past year. The objective of the review was to determine whether the RCMP had implemented appropriate controls, including policies, procedures and processes, to ensure that its collection of subscriber data without a warrant was in compliance with sections 4 and 5 of the Privacy Act.

Furthermore, we were hoping to provide additional transparency by answering the following questions:

- How frequently does the RCMP collect subscriber data without a warrant?; and

- Did the RCMP have appropriate justification for its warrantless requests of subscriber data?

As the RCMP’s information management systems were not designed to identify files which contained warrantless access requests to subscriber information, we were unable to select a representative sample of files to review. Consequently, we were unable to assess the sufficiency of controls that may exist or if the collection of warrantless requests from Telecommunications Service Providers (TSPs) was, or was not in compliance with the collection requirements of the Privacy Act.

In addition, we could not determine:

- How frequently the RCMP collects subscriber data without a warrant; or

- Whether the RCMP had appropriate justification under the Privacy Act to request subscriber data without a warrant.

Our Office therefore recommended that, in order to promote greater transparency surrounding warrantless requests for subscriber information made by the RCMP to Telecommunication Service Providers, the RCMP should implement a means to monitor and report on its collection of this information. While the review focused on the RCMP, the resulting recommendation is one that all federal institutions should follow.

The full text of the review can be found in section 4 of this report.

In the weeks following the reports of about the 1.2 million telecommunications requests, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights began hearings on Bill C-13, the latest federal attempt at “lawful access” legislation.

When Bill C-13 was initially introduced in November 2013, our Office noted that it did not contain the much-criticized provision of its predecessors to compel telecom companies to provide subscriber information to authorities upon request without a warrant. Bill C-13 did however raise other concerns including its relatively low threshold for obtaining a warrant in certain cases, and a new immunity clause that, as Privacy Commissioner Daniel Therrien explained in his June 10th appearance before Committee, “could lead to a rise in additional voluntary disclosures and informal requests.”

Transparency builds trust

An international call for greater transparency

At the 35th International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners, which took place in September 2013 in Warsaw, Poland, our Office joined other data protection authorities in agreeing upon and issuing a resolution calling for increased openness on the part of federal agencies.

While testifying on Bill C-13, Commissioner Therrien also said, “Canadians expect that their service providers will keep their information confidential and that personal information will not be shared with government authorities without their express consent, clear lawful authority or a warrant.”

The essence of privacy is the ability of individuals to control their own personal information. Essential to informing this ability is transparency, which formed a major part of the privacy discussions in the public sector during the past year.

Advocates on both sides of the debate ignited by the surveillance revelations agreed that, by and large, the data divulged were mere snapshots of activity and lacked the context of the bigger picture.

Being more open about their operations to the extent possible given the sensitivity of their activities, would allow national security and intelligence agencies to dispel Canadians’ fears and gain their trust. Such efforts would help achieve the important objective of building Canadians’ confidence in the conduct of their national security agencies. Doing so would also help these organizations meet citizens’ expectations as forged by today’s information age.

But, while recognizing that some secrecy will always be a necessary element of their activities, intelligence agencies have been slower in raising their levels of transparency.

In a letter to CSEC Chief John Foster, former Privacy Commissioner Jennifer Stoddart raised the importance of greater transparency, noting that “open and accountable government is a laudable goal in all contexts, critical for gaining and maintaining the trust of its citizens.” In response, CSEC committed to getting its Personal Information Banks (descriptions of personal information held by federal organizations and retrievable for administrative purposes) online (which it did in 2013) and proceeded to expand the materials on its website, providing Canadians with more information about how the agency works.

Our January 2014 Special Report Checks and Controls called for further means of enhancing the transparency of intelligence activities carried out by Canadian federal institutions.

Privacy spotlighted as never before and a seminal ruling

In retrospect, it’s difficult to think of a year where privacy issues were as dominant in the media and Parliament as the one chronicled in this report.

Apart from the surveillance revelations themselves, our Office noted a general upswing in interest about privacy from the media, across the board. Media calls to our Office were up 40 percent from April 1, 2013 to March 31, 2014 compared to the same period a year before. And that increase came before the news about the 1.2 million access requests made to Canadian telecommunications companies, which generated unprecedented interest from reporters.

Just over a year after the surveillance revelations began, this intense 12-month period was capped by a seminal ruling from the Supreme Court upholding the right to personal privacy in R v. Spencer.

The Court ruled that there is indeed a reasonable expectation of privacy attached to information about telecom company subscribers when such information could be used to unlock sensitive details about an individual’s online activities. And therefore, unlike simple phonebook information alone, a name and address when linked with an IP address is worthy of constitutional protection. On a practical level this means that, outside exigent circumstances or a reasonable law providing lawful authority, authorities need prior court authorization to obtain such information.

Our Office greeted this ruling with immense satisfaction, as it affirmed the sensitivity of subscriber information and recognized the escalation of risks to privacy which have dawned with the onset of the online age. It should also serve to provide clarity to law enforcement and telecommunications service providers to adjust their processes and practices accordingly.

Broader implications of R v. Spencer

Some key policy principles and privacy lessons reinforced by the Supreme Court’s ruling include:

- Lawful access and government searches cannot be regulated solely on the basis of the data viewed in isolation – what the gathered information can, in turn, reveal must also be considered as a critical factor [par.26, 30-33];

- The invasiveness of a search must be determined by the potential impact upon the individual – not the illicit nature of the material sought or crime thwarted [par.18, 36];

- Contemporary conceptions of informational privacy as protected by the Charter must include elements of secrecy, control and anonymity [par. 38];

- Much of the information citizens exchange in both the real world and online is done with the specific understanding these ideas and opinions will not be recorded and linked specifically to them [par. 42-43, 45].

Since the ruling, many Canadian telecommunications providers have adopted new policies stating that they will only provide subscriber information to authorities when the requests have been authorized by the courts.

As well, in the wake of the surveillance revelations, many online service providers have begun offering annual transparency reports revealing how many requests they receive for subscriber information from authorities.

Looking over the horizon

While the year featured revelations that some people found concerning and even disturbing from a privacy perspective, it was also 12 months where such concerns led to positive changes that gave the public and policymakers greater insight into how personal information may be collected by authorities.

Yet important questions still remain about how that information is used by authorities, calling for greater transparency not only from private sector companies, but also from public sector organizations. On that front as well, the year gone by may have provided an inkling of hope, as reflected in testimony by CSEC Chief John Forster to the Senate Committee on Defence and National Security in January 2014. Noting that CSEC had been “a well-hidden organization for tens and tens of years” Foster continued:

“One of the challenges I have, as the chief of that organization, is for us to be far more transparent and open as far as we can be within the confines of national security about what we do. We think that's important as another way of ensuring public trust and confidence in the work we're doing.”

A similar sentiment was voiced by former CSE Commissioner Robert Décary who, in his 2013 annual report, stated that “the greater the transparency, the less sceptical and cynical the public will be” about intelligence activities. The same position has been echoed by current CSE Commissioner Jean-Pierre Plouffe, who in his inaugural annual report stated that, “transparency is important to maintain public trust,” and that “it is my goal to carry on my predecessor's work to be more informative and transparent about the activities of my office and of CSEC.”

The closing months did indeed bring reasons to hope that the heightened public interest and discussion might lead to greater transparency and more security for personal information in the year ahead.

Looking forward, at the time of this report’s writing, there is legislation before Parliament holding potentially significant impacts upon privacy in the form of the aforementioned Bill C-13. It contains measures that seek to ease the ability of organizations to comply with authorities when faced with requests seeking access to subscriber information.

As it stands, we are concerned that these proposed measures would lead to excessive disclosures that would be invisible to the individuals concerned and to our Office.

In preparing for future appearances before Committee examining this Bill, we are considering how to best advise parliamentarians on the significance of the Spencer decision and the importance of transparency for government in building and maintaining trust with citizens.

4. Review of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police – Warrantless Access to Subscriber Information

Section 37 of the Privacy Act

Introduction

For over a decade, the Government of Canada has been studying various proposals that would authorize specified government agencies to obtain personal information held by Telecommunication Service Providers (TSPs). Since 2005, these lawful access proposals have been set out in eight separate bills introduced by the Government of Canada. As of this writing (October 2014) Parliament is still considering legislation that would modernize police investigative techniques, but also have far-reaching implications for online privacy. As of this writing, Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Canada Evidence Act, the Competition Act and the Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Act(also known as the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act ), is at the Report stage before the House of Commons.

Representatives of Canadian law enforcement agencies have been calling for new police powers to be codified in lawful access legislation for some time. They have stated that Internet use and evolving telecommunication infrastructures in Canada have created hurdles for investigations. As part of their mandated responsibilities, law enforcement agencies seek to identify criminal activity and those carrying out criminal activity online, in the context of a lawful investigation. As a result, law enforcement agencies may seek subscriber information for a wide range of criminal investigations, including child exploitation, drugs and organized crime, abducted persons, cyberbullying and financial crimes, or other public safety emergencies such as suicide threats or missing persons. The legal requirements for obtaining subscriber information may vary depending on the nature of the information sought. As well, the information requested varies, and may be limited to the name and address associated with a phone number, or includes the name associated with an Internet Protocol (IP) address.

Importance for Canadians

There is significant public interest concerning government surveillance and requests by law enforcement bodies to obtain subscriber information without prior judicial authorization.

Prior to the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R. v. Spencer, many Telecommunications Service Providers released subscriber information in response to law enforcement requests without prior judicial oversight. Some of these requests involved information which could allow government agencies to access information that could be subsequently linked to personal information and other sensitive information, such as Internet usage.

The practice of law enforcement agencies seeking subscriber information without prior judicial authorization is not well understood by Canadians. Indeed, limited information is available about such requests, including the frequency with which they were made, and what information was sought.

It was in this context that our office decided to review the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in order to provide greater clarity regarding the practice of obtaining subscriber information from Telecommunications Service Providers (TSPs) without a warrant.

About the RCMP

The RCMP operates under the authority of the RCMP Act. A Commissioner heads the organization under the direction of the Minister of Public Safety Canada. The RCMP is the largest police force in Canada. It has a broad mandate which covers international and domestic roles.

The RCMP enforces federal laws across the country, and provincial/territorial laws in all provinces and territories – excluding Ontario and Quebec. The RCMP also provides investigative, operational and technical support services to more than 500 Canadian law enforcement and criminal justice agencies.

The RCMP operates in approximately 150 municipalities, 600 aboriginal communities and at three international airports. The RCMP has approximately 29,000 employees, including regular and civilian members, and public service personnel both in Canada and abroad.

In the course of carrying out its mandate, the RCMP gathers various data and requests information from a wide variety of individuals, as well as from public and private sector sources. More specific to our review, the RCMP, in the course of law enforcement investigations, may make requests to TSPs without a warrant to obtain subscriber information.

Background

On October 24, 2013, the Privacy Commissioner issued a notice of review to the RCMP Commissioner under section 37 of the Privacy Act. The notice indicated that we would conduct preliminary work that may lead to an audit of the RCMP’s collection of subscriber data without a warrant from TSPs.

Objective

The objective of the review was to determine whether the RCMP had implemented appropriate controls, including policies, procedures and processes, to ensure that its collection of subscriber data without a warrant was in compliance with sections 4 and 5 of the Privacy Act.

Furthermore, we were hoping to provide additional transparency by answering the following questions:

- How frequently does the RCMP collect subscriber data without a warrant?; and

- Did the RCMP have appropriate justification under the Privacy Act for its warrantless requests of subscriber data?

Given the federal government’s statements and commitments to openness and transparency, we expected to find that the RCMP’s records would enable reporting on the above questions.

Observations

The Privacy Act restricts the collection of personal information by federal entities to that which is related to an operating program or activity. During our review, we wanted to assess whether the RCMP’s warrantless access requests to Telecommunication Service Providers (TSPs) for subscriber information were made in keeping with the above requirement.

During the course of our review work we interviewed over 50 individuals. These included senior RCMP officials, field officers who have made warrantless requests for subscriber information, and information technology specialists who are in charge of managing and extracting information from the RCMP’s investigative databases. We also interviewed specialists from the telecommunications industry familiar with these types of requests. As well, we reviewed the RCMP’s policy related to the recording of law enforcement activities in their investigative databases.

This policy requires that the collection and use of operational information is subject to the provisions of the Privacy Act. Although RCMP policies do not specifically address the practice of requesting subscriber information from TSPs without a warrant, they do apply to the full range of RCMP operational activities, which would include this type of collection.

The RCMP informed us that its primary record management system receives approximately two million new incident entries every year. We undertook searches of this system, and in only limited instances were we able to identify a link between requests made for warrantless access to subscriber information and the files that contained such requests. We found that other than through a manual review of each case file, the RCMP does not currently have the capacity to produce a report that would identify some or all of the particular operational files in which an access to subscriber information was made without a warrant, and report on the frequency of such requests. The RCMP stated that its records management system was not designed for this purpose.

The RCMP indicated that its records management system for operational case files was designed to support investigations and to respond to legislative requirements to report certain crime statistics to Statistics Canada. The RCMP further explained that the systems were not designed to be able to report on all the instances, in the aggregate, where requests for subscriber information without a warrant were made. The RCMP also stated that compiling such information is complicated by the fact that a complex criminal case may involve numerous warrantless requests for customer names and addresses related to phone numbers. In addition, the method and type of information requested varies depending on the nature of the case, and the requirements of the TSP.

The only area where we were able to review files containing warrantless access requests for subscriber data was at the RCMP’s National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC). However, the NCECC requests only represent a subset of all warrantless requests for subscriber information made by the RCMP. Our review of NCECC files indicated that the warrantless access requests for subscriber data were linked to ongoing investigations. However, we are unable to extrapolate these results beyond these files to areas other than the NCECC.

The RCMP itself recognized the merit in capturing statistical information on warrantless requests for subscriber data. On January 12, 2010 the Assistant Commissioner for Technical Operations issued a memorandum instructing that front line officers begin reporting warrantless requests for subscriber information to TSPs. This memorandum was issued to support the possible reintroduction of Bill C-47, Technical Assistance for Law Enforcement in the 21st Century Act.

The RCMP stated that as Bill C-47 did not progress beyond the second reading stage in Parliament, this data collection was never fully operationalized. However, the memorandum noted that at the time it was issued, Bill C-47 had been at the second reading stage before Parliament and had already died on the order paper as Parliament had prorogued in December 2009. Our reading of the memorandum, and its timing, suggest that the purpose of the request for officers to compile statistics on requests for subscriber information was to gather information to demonstrate the need for lawful access legislation generally, which was eventually reintroduced in November 2010 as Bill C-52, Investigating and Regulating Criminal Electronic Communications Act and thereafter as Bill C-30, An Act to enact the Investigating and Preventing Criminal Electronic Communications Act and to amend the Criminal Code and other Acts, in February 2012.

On June 13, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision in R. v. Spencer; that decision had a direct impact on our ongoing review activities. In that case, a unanimous Court held that there was a reasonable expectation of privacy under section 8 of the Charter with respect to subscriber information that could link an individual to his or her online activities. The Court concluded that, in that case, the information was unconstitutionally obtained since police did not have any lawful authority to obtain such information in the absence of exigent circumstances or a reasonable law. The RCMP has indicated that it has adjusted its investigative efforts to align them with the Spencer decision. Given that the RCMP’s primary records management system was not designed to identify warrantless access requests, and the impact that the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling (R. v. Spencer) now has on the RCMP’s ability to collect subscriber data without a warrant, we decided against proceeding with the review.

Ultimately, our efforts to review files, combined with our interviews with RCMP personnel, did not allow us to determine whether the RCMP, as a whole, was compliant, or non-compliant, with the provisions of the Privacy Act with respect to the collection of subscriber information without a warrant. Moreover, other than through a manual review of all case files stored, the RCMP does not have a means to demonstrate its compliance in this regard.

Recommendation: In order to promote greater transparency surrounding warrantless requests for subscriber information made by the RCMP to Telecommunication Service Providers, the RCMP should implement a means to monitor and report on its collection of this information.

RCMP Response

The RCMP’s primary responsibilities are to preserve the peace, prevent crime and investigate offences against the laws of Canada. In executing its mandate, the RCMP is fully committed to respecting the laws of Canada, including the Privacy Act. The RCMP’s records management systems were designed to meet investigative and evidentiary standards and not for the purpose of reporting aggregate data on the origins of information collected during the course of its investigations. Notwithstanding, to ensure adherence and compliance with the laws of Canada, the RCMP maintains an extensive suite of operational policies, practices and standards.

While it is anticipated that the number of warrantless requests will be reduced in light of the R. v. Spencer decision, warrantless access will continue to be sought in specific situations, such as exigent circumstances or where authorized by a reasonable law. The RCMP will establish a working group to explore mechanisms which are both efficient and cost-effective to better monitor and report on warrantless requests for subscriber information. A report in this regard will be presented to our Departmental Audit Committee by April 2015.

Additionally, as a result of the R. v. Spencer decision, the Department of Justice and the Public Prosecution Service of Canada are working with the interdepartmental community to examine the decision and its implications. The RCMP will fully comply with all new requirements as the implications of the decision are further determined.

Conclusion

Through our review we had intended to inform Parliament and Canadians about the RCMP’s use of warrantless access requests to Telecommunication Service Providers (TSPs) for customer data.

As the RCMP’s information management systems were not designed to identify files which contained warrantless access requests to subscriber information, we were unable to select a representative sample of files to review. Consequently, we were unable to assess the sufficiency of controls that may exist or if the collection of warrantless requests from TSPs was, or was not in compliance with the collection requirements of the Privacy Act.

In addition, we could not determine:

- How frequently the RCMP collects subscriber data without a warrant; or

- Whether the RCMP had appropriate justification under the Privacy Act to request subscriber data without a warrant.

Keeping accurate records of warrantless requests for subscriber information is consistent with the Government of Canada’s commitment to transparency. Furthermore, accurate record keeping could provide the necessary evidence to justify the need to implement lawful access related legislation.

About the Review

Authority

Section 37 of the Privacy Act empowers the Privacy Commissioner to examine the personal information handling practices of federal government organizations.

Objective

The objective of the review was to determine whether the RCMP had implemented appropriate controls, including policies, procedures and processes, to ensure that its warrantless collection of subscriber data was in compliance with sections 4 and 5 of the Privacy Act.

Criteria

Review criteria were derived from the Privacy Act and Treasury Board Secretariat policies, directives and standards related to the management of personal information.

We expected to find that the RCMP has:

- Policies, practices and procedures to ensure that warrantless access requests made to Telecommunication Service Providers (TSPs) only collect personal information that is related to operating programs; and

- Consistently documented its warrantless access requests to TSPs, further to the Government of Canada’s commitment to openness and transparency.

Scope and approach

Examination activities were conducted at the RCMP’s headquarters in Ottawa and with selected RCMP officials across the country.

The review examined policies, practices procedures and electronic files about warrantless access requests. Evidence was also obtained from the examination of records, interviews with 52 officials, demonstrations of systems and other review tests.

The review did not include a review of requests made: with a warrant, using mutual legal assistance treaties (MLAT’s), for telephone numbers, or to sites that provide internet search services.

The review commenced on October 24, 2013 and was halted in June 2014 in light of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R. v. Spencer.

Standards

The review was conducted in accordance with the legislative mandate, policies and practices of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

Review team

Steven Morgan

Tom Fitzpatrick

Sylvie Gallo Daccash

Ivan Villafan

5. The Year in Review

Privacy Impact Assessments

Privacy Impact Assessments (PIAs) are used to identify the potential privacy risks of new or redesigned federal government programs or services. They are meant to eliminate or reduce those risks to an acceptable level.

PIAs take a close look at how federal government institutions protect personal information as it is collected, used, disclosed, stored and ultimately destroyed. These assessments help create a privacy-sensitive culture in government departments. It is important they are prepared well in advance of a new initiative (or changes to an existing one) being implemented in order to address privacy risks early and up front. Organizations that make PIAs a priority stand to benefit by lessening the possibility of adverse events, such as data breaches, while demonstrating an active commitment to transparency and respect for the privacy of Canadians.

According to the Treasury Board Secretariat Privacy Impact Assessment Directive, federal government institutions are responsible for undertaking PIAs for new or substantially-modified programs or activities involving the use of personal information for decision-making purposes which affect individuals. They must demonstrate that privacy risks have been identified and effectively mitigated. Our Office receives copies of these assessments for review, and, when appropriate, we give institutions advice and recommendations for improving their personal information-handling practices. While most institutions accept and follow our advice, our recommendations are non-binding.

Border crossing information

PIAs reviewed by the OPC over the past fiscal year indicate a trend towards an increased collection of personal information at borders and an expansion of the sharing and uses of such information. A large part of this increased surveillance stems from the Entry/Exit initiative, which is one of a number of initiatives that have been developed under the Canada-U.S. Beyond the Border perimeter security agreement. The collection of exit information at land borders is based on an exchange between Canada and the U.S., so that a record of entry into one country becomes a record of exit from the other. Information on individuals exiting Canada has not previously been routinely collected by our government.

Phases I and II of Entry/Exit involved the exchange of entry information between Canada and the U.S. of third country nationals and permanent residents crossing land borders. Upon reviewing the PIA for Phase II, our Office learned that the CBSA planned to retain the personal information collected under the Entry/Exit program for 75 years. We asked the CBSA to provide a justification for the planned retention period. In response to our recommendation, the CBSA reduced the retention period to 30 years, with depersonalization occurring after the first 15 years. However, we have requested and await a justification for the necessity to retain the information for this time period and have asked all other institutions that will also collect this information to justify retention periods.

Should the program move forward, Phase III will expand the surveillance to Canadian and U.S. citizens crossing by land, while Phase IV will include the collection of exit records for all travellers leaving Canada by air. Commercial air carriers will be required by law to give CBSA passenger manifests for outbound flights. It is our understanding that new legislation will need to be passed in Parliament, and regulatory changes will be required for this contemplated expansion.

The CBSA justified the initial phases of the program as necessary for border integrity and immigration enforcement, indicating that enforcement and removal efforts for individuals who overstayed their visa limits would be better focused if the Agency had more information on who had left.

Plans for the next phases of the Entry/Exit program contemplate not only collecting exit data from all travellers, but using that personal information for wider purposes. These include use by law enforcement agencies, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) for validating residency requirements, and Employment and Social Development Canada for determining employment insurance eligibility. Exit records may also be shared with other government departments, such as the RCMP, the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS), and the Canada Revenue Agency. In 2014-2015, the OPC expects to receive specific PIAs for proposed new uses of personal information from the Entry/Exit program. We have recommended that each of these expanded uses be demonstrated as necessary and effective, be undertaken in the least privacy-invasive manner possible and be designed so any loss of privacy is in proportion to a substantial societal benefit.

Our Office continues to meet with officials from CBSA and other departments, and expects more detailed PIAs to come in early 2015.

Cross-border biometrics

Another government initiative raising many of the same privacy concerns is the Temporary Resident Biometrics Project (TRBP), managed jointly by CIC, the CBSA, and the RCMP. Beginning in 2013, citizens from 29 countries and one territory who apply to visit, study or work in Canada have been required to give their fingerprints and have their photographs taken as part of their visa application.

The TRBP was first presented to our Office as a way to screen applicants for admissibility, confirm their identities during the application process, and verify identities of visa holders when they entered Canada. On that basis, the government demonstrated that such verification was an appropriate use of biometrics and involved minimal privacy risks, so long as appropriate safeguards were used.

However, the project was expanded to allow the RCMP to retain fingerprints and other information collected during the application process for 15 years. These could then be matched against entries in the RCMP’s criminal fingerprint database and latent prints lifted from crime scenes.

CIC indicated that visa applicants consent to this use on their application forms. In our continuing work on the PIAs for this project, our Office expressed concerns about whether visa applicants are fully informed of the potential uses of their fingerprints. We also questioned whether the lengthy and uniform retention of fingerprints of individuals not charged with, or convicted of, any criminal offence is justifiable. We recommended that CIC carefully review its consent mechanisms and retention periods.

CIC responded by saying that if a government institution possesses personal information that could identify a person of interest to law enforcement, it should disclose this information. We advised that this is a broad interpretation of acceptable disclosures and that the Privacy Act sets specific restrictions on the circumstances under which personal information collected by a government institution may be released to law enforcement. We continue to consult with the involved departments on this initiative.

Canada Revenue Agency security screening

Judging from PIAs reviewed over the past year, there appears to be a trend across government toward more intrusive security screening with regard to government employment. This can include the collection of personal information from social media and “integrity checks,” which may include intrusive questions to potential employees about subjects, such as gambling, personal finances, relationships, and drug and alcohol use. These screening measures are in addition to the federal government’s existing security requirements.

One example is the Canada Revenue Agency’s (CRA) “Reliability Status+” screening process. This enhanced screening applies to an estimated 300 positions said to require a high degree of trust and decision-making power. The process proposed in the PIA included fingerprinting, credit checks, Law Enforcement Records Checks (more extensive than a criminal records check), tax compliance verification, open source verifications, including social media information, and the completion of an intrusive Reliability Questionnaire.

Our review of the PIA identified risks to privacy posed by the addition of numerous privacy intrusive checks, particularly the questionnaire which contained questions of a broad nature that could lead to over-collection of personal information.

After our consultations, the CRA revised or removed some of the more invasive parts of the screening process and dropped the questionnaire altogether.

Social Security Tribunal

Last year, the Government changed and amalgamated the tribunal system for hearing appeals of Employment Insurance, Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security decisions, without fully weighing the privacy and security implications to the personal information of thousands of Canadians.

In the past, a board of more than 1,000 part-time referees heard the appeals in three-person panels working from government offices. Under the new system, 74 full-time members of a Social Services Tribunal rule on the appeals by teleworking from home offices.

The OPC received a PIA from Employment and Social Development Canada only after the new tribunal began operating in April 2013. Many of the policies and procedures for safeguarding the personal information of appellants were still under development, including safeguards for teleworking and security assessments of tribunal members’ home offices. When this report was being prepared in early September 2014, our Office had still not received the results of these assessments, which are key to addressing any privacy risks.

Data Breaches

For the third consecutive reporting period, the number of data breaches voluntarily reported to the OPC by departments and agencies reached a record high.

Any loss or unauthorized disclosure of personal information constitutes a data breach. Sometimes the affected individuals didn’t know about the breach; in other cases people were officially told or found out through media reports.

Yet, as noted in previous annual reports, we don’t know whether there have really been more data breaches in the year under review, or whether institutions have been more assiduous in reporting them. Such uncertainty should dissipate substantially in the future thanks to the May 2014 updates to the Directive on Privacy Practices from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) requiring federal institutions to report all material data breaches to our Office and TBS.

Our Office also worked closely with TBS to provide guidance about what amounts to a “material breach.” At the time of this report’s writing, institutions showed that they are still undergoing some growing pains in getting used to the new Directive. Since the Directive’s coming into effect, it appears that more breaches are being reported to our Office than to TBS, when in fact each incident should be reported to both of our organizations.

Looking back at 2013-2014 when voluntary reporting prevailed, the OPC received reports of 228 data breaches across the federal government, more than double the 109 from the previous fiscal year. Accidental disclosure (i.e. human error) accounted for just over two-thirds of those breaches.

One particularly enormous data breach was the 2012 loss from Employment and Social Development Canada of an external hard drive containing the personal information of 583,000 student loan recipients.

A special OPC investigative report tabled in Parliament in March 2014 detailed how the hard drive was left unsecured for extended periods of time, not password protected and held unencrypted personal information. Arising out of the investigation, the OPC produced tips for federal institutions on the use of portable storage devices.

No organization is immune from the possibility of a data breach. Even our Office has experienced this type of event, with the loss of a hard drive containing employee information that went missing when we moved our head office from Ontario to Quebec. It is expected that the Privacy Commissioner, Ad Hoc will reference this event in his contribution to our 2014-2015 annual report on the Privacy Act.

Tips for federal institutions using portable storage devices

A four-page OPC tipsheet on using portable storage devices provides employees in federal departments and agencies with checklists about the four kinds of controls that provide protection against data breaches – physical, technical, administrative and personnel security.

Physical controls, for example, stress the importance of protecting devices not in use by placing them in locked cabinets or in storage areas where access is restricted. Technological controls would include encryption or strong passwords, with training for employees in each.

Under administrative controls, the tipsheet recommends assigning serial numbers to devices so they can be tracked and using portable storage devices to store personal information only as a last resort.

Personnel security controls encompass regular mandatory training about security and privacy, and monitoring the use of personal storage devices by employees to ensure policies and procedures are being followed.

Parliament

As an Agent of Parliament, our Office values opportunities to advise parliamentarians on the privacy implications of legislation and the issues they study. The year under review included many important discussions.

Bill C-13: a new iteration of “lawful access”

Vigorous and prolonged debate followed the introduction in November 2013 of Bill C-13, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act.

Some critics characterized the legislation as a Trojan horse. Drafted in the wake of widely publicized suicides by young girls who had been subjected to cyberbullying, Bill C-13 would make it illegal to distribute intimate images without consent and remove barriers to getting such pictures scrubbed from the Internet.

However, the proposed legislation would also give police and other authorities new tools to preserve records of computer use and electronic emissions, track and trace various online activities of suspects, make it easier to get court approval for electronic surveillance and expand lawful access for a wider range of investigating agencies.

Following its November 2013 tabling, our Office carried out an extensive analysis of Bill C-13 leading up to the June 10, 2014 appearance of Commissioner Daniel Therrien before the House of Commons Justice and Human Rights Committee.

In his statement, the Commissioner recommended splitting the Bill, with cyberbullying going to Parliament for quick action while allowing for a focused and targeted review of the lawful access provisions. He summarized the OPC’s four main concerns:

- Lowering the threshold for state access to electronic personal information from the existing “reasonable and probable grounds” of illegality to only “reasonable suspicion” of illegality;

- Extending the authorities who could use the new surveillance powers beyond police officers to include an ill-defined category of “public officers” such as mayors, reeves, fisheries officers, customs officers and any federal or provincial officer;

- Guaranteeing legal immunity to an individual or organization that voluntarily provides information to an investigator without court authorization; and

- The absence of any transparency regime requiring regular reporting on the use of any of the new powers.

A transcript of the Commissioner’s remarks and a further detailed written submission can be found on our website.

The Committee reported to the Commons on Bill C-13 on June 13; no further action was taken before the summer recess.

Seeking salary figures

The OPC has long been a strong proponent of open government as a means to enhance transparency and accountability commensurate with the protection of personal privacy. On June 5, 2013, then-Commissioner Jennifer Stoddart reinforced this view in an appearance before the Commons Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics.

The committee was considering Bill C-461, the CBC and Public Service Disclosure and Accountability Act, a private member’s bill.

The legislation would have amended the Privacy Act to make the salaries of the top-paid federal public servants “non personal” so they could be released under an Access to Information Act request. It would also have done the same for the salary ranges of all other public servants and for the details of expenses reimbursed to any federal employee.

After reviewing current practices in the public service, provincial governments and the private sector, Commissioner Stoddart told the committee that “the disclosure of the salaries of the most senior officials in the federal public sector does not represent a significant privacy risk relative to the goal of transparency and the broader public interest.”

She added that disclosing salary ranges and expense reimbursements also had no serious privacy implications and is something the OPC would readily do in response to an access request.

Bill C-416 died on the Commons order paper in February 2014.

Agents of Parliament combine efforts

The importance of enhancing transparency and accountability to Parliament and Canadians also figured into written comments by Interim Commissioner Chantal Bernier and the six other designated Agents of Parliament, such as the Auditor General and the Commissioner of Official Languages.

These seven individuals, all appointed by Parliament, were commenting on a private member’s bill, C-520, the Supporting Non-Partisan Agents of Parliament Act.

Among other provisions, the proposed legislation would require that people being considered for jobs in the offices of Agents of Parliament disclose their political affiliations and activities for the last 10 years.

The Bill also states that an Agent, such as the Privacy Commissioner, must examine a written allegation from an MP or Senator that an employee of an Agent’s office has been partisan in the performance of their responsibilities. The Agent would be legally obliged to submit a written report to the Senate and Commons speakers.

In a written submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics, the seven Agents, while supporting the general principles of accountability and impartiality, criticized Bill C-520 as being overly broad, vague and conflicting with existing laws covering public service employment.

The Committee reported to the Commons on Bill C-520 on May 26 with amendments; no further action was taken before the summer recess.

Privacy Compliance Audits

Under the Privacy Act, the Commissioner may audit the relevant privacy practices of federal departments and agencies and recommend remedial actions when needed. Although the Act provides no enforcement powers, the Commissioner may publish the findings and recommendations.

The OPC typically follows up with audited institutions two years later, asking what actions they have taken to address our recommendations. In 2013-2014, we launched two new audits and followed up on two others.

Follow-ups: In 2011 we audited two RCMP databases: one stores information on crimes and criminals, which can be retrieved by police agencies across Canada; the other is the primary operational records management system for the RCMP. Details of our audit and recommendations can be found on our website.

The RCMP reported that four of our six recommendations had been fully implemented and the other two substantially so. For example, to deal with personal information being kept longer than necessary in the records management system, the RCMP informed us that it purged the backlog of all outstanding records and now erases files daily as required. The RCMP also reported that all police agencies, except for those in Quebec, where provincial legislation prevents individual police services from entering into an agreement with a federal agency, have now signed formal memoranda of understanding, which include provisions for privacy protection of personal information from the crime and criminals database.

In 2011, we also reviewed privacy policies and practices at the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA), an organization familiar to all air travellers. Details are available on our website.

CATSA reported that 10 of our 12 recommendations have been fully implemented and the other two substantially so. These include:

- No longer telling police if CATSA finds domestic travellers carrying large sums of money;

- Developing a pamphlet to explain its collection, use, disclosure, retention and disposal of personal information related to boarding passes; and

- Introducing new software in 2013-2014 that shows a stick figure of someone subjected to a full-body scan instead of an outline.

New: Although portable storage devices, such as USB keys and external hard drives, can provide flexibility and convenience, they can also present inherent security and privacy risks, as government departments, such as Employment and Social Development Canada have discovered.

To obtain a better understanding on the use of portable storage devices within federal institutions, the OPC conducted a survey of departments and agencies and selected 17 for further examination in a cross-government audit. The audit will gauge whether these institutions have established and implemented policies, procedures and adequate controls to protect personal information stored on portable storage devices. We aim to complete the audit in 2014-2015.

Our Office also launched a review of RCMP requests without a judicial warrant to telecom and Internet companies for basic subscriber information. This work and its outcome are detailed in section 4 of this report.

Presented: During 2013-2014, the OPC also published our formal audits of the Canada Revenue Agency and the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), both of which were featured in last year’s annual report.

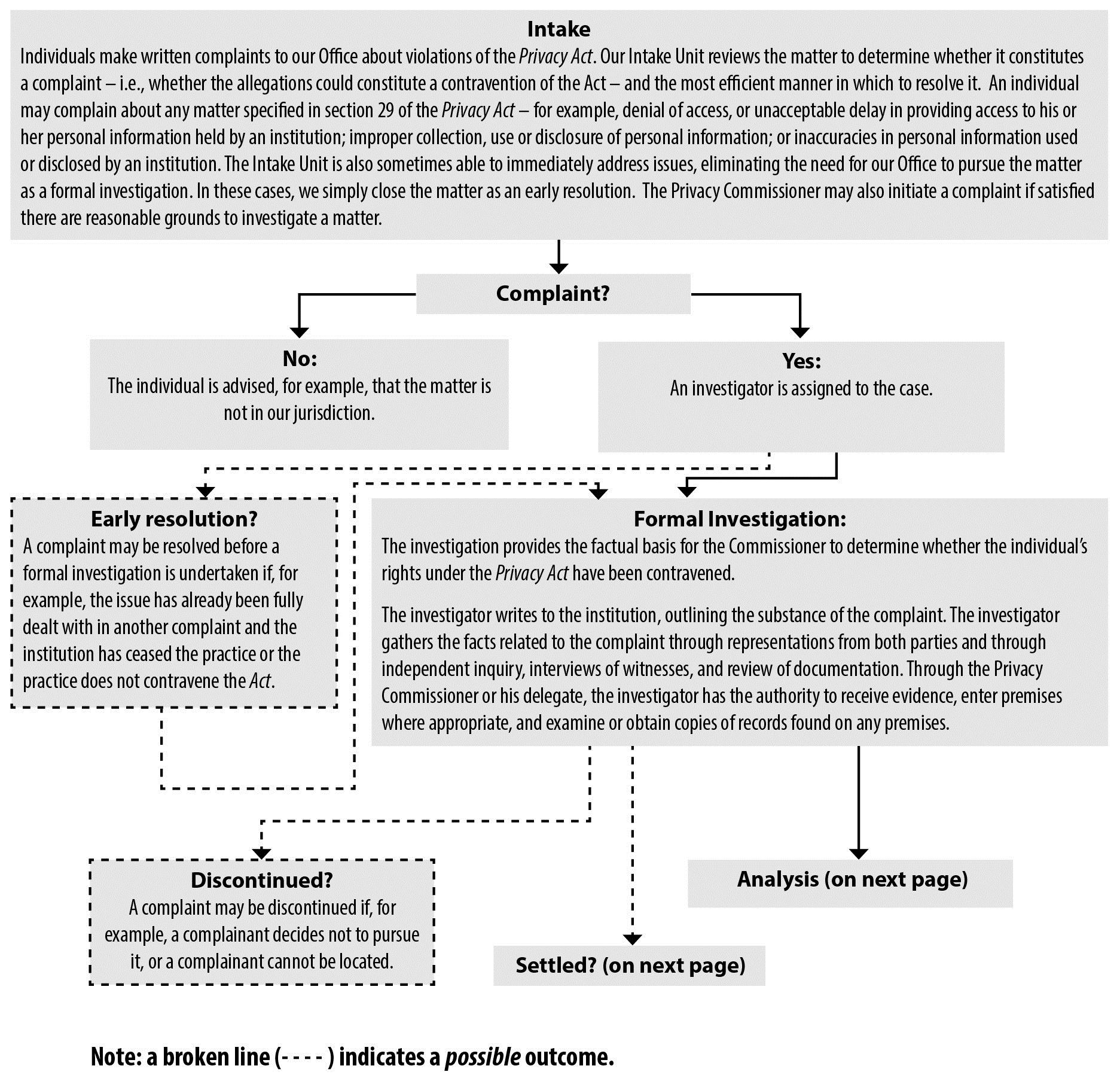

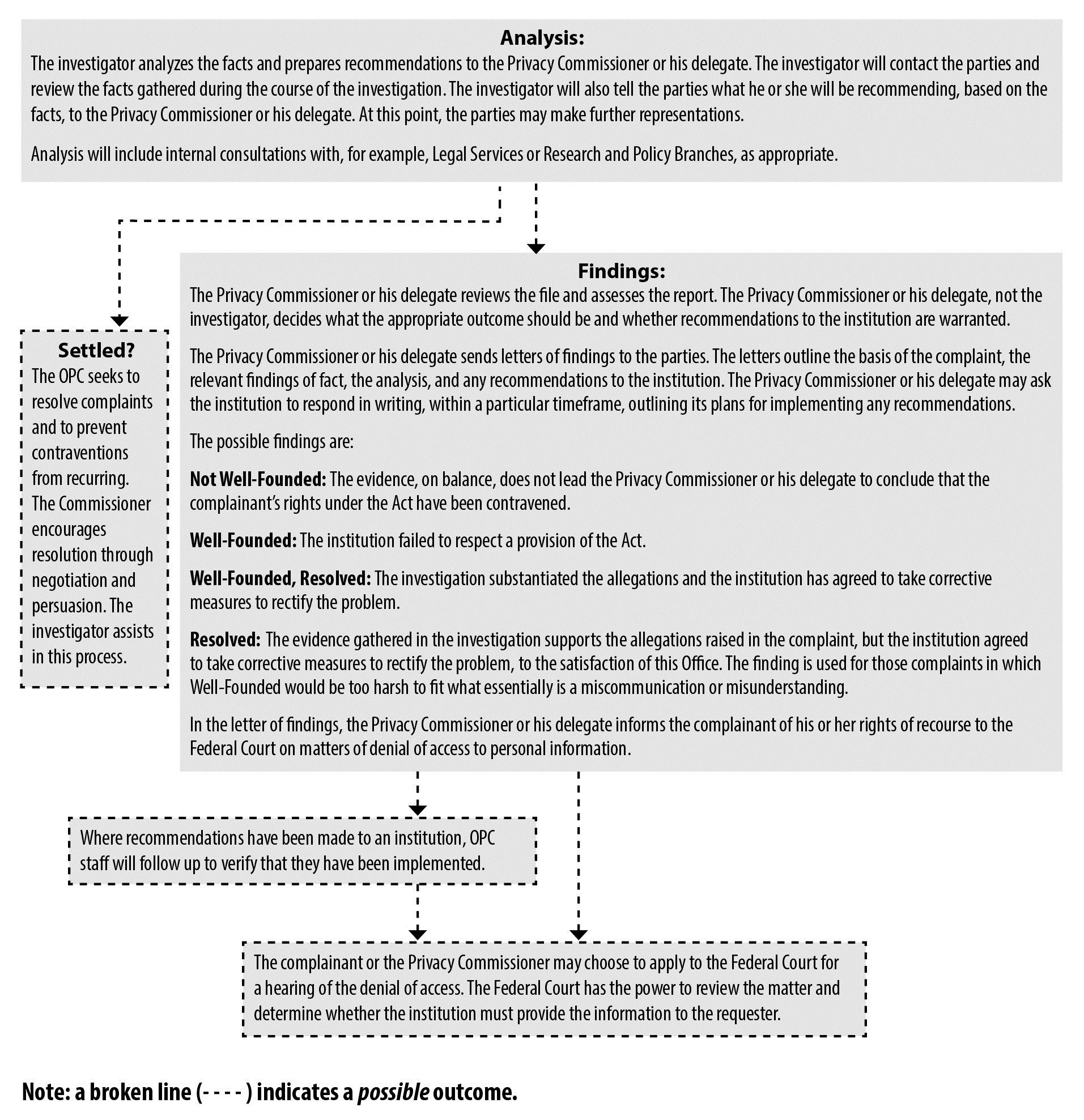

Investigations

A close look at the numbers show that the Office of the Privacy Commissioner continued to profit from measures introduced in previous years to increase efficiency in processing complaints. Against the ongoing challenge of a growing volume of complaints and their increasing complexity, the Office continued to see improvements in treatment times.

The Office accepted 1,777 complaints under the Privacy Act during 2013-2014. This was significantly lower than the previous year. The number for the previous year however was unusually high, because over 1,200 complaints were received in relation to two major data breaches at Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC). Excluding complaints associated with those two breaches, this leaves a year-over-year increase of approximately 700 complaints in 2013-2014.

On the surface, average treatment times for complaints came to 10.9 months for 2013-2014. Removing the number of ESDC-related breach complaints from the comparisons however shows that average treatment times improved from 8.9 months in the previous year to 8.1 in 2013-2014.

This represents a marked improvement from five years ago in 2008-2009 when the average was 19.47 months. Year over year, trends indicate that complaints are growing in both their volume and complexity. Against this backdrop, average treatment times have generally and steadily continued to improve, thanks to a series of efforts to redistribute internal resources, and improve and modernize processes.

For example, the early resolution investigation process accounted for 345 of our closed files, compared to 299 in 2012-2013. In addition to handling more complaints through such negotiation and conciliation this year, our Office successfully reduced the average treatment time for early resolution cases by four days (from 2.25 months to 2.11 months as shown in the detailed tables found in Appendix 2).

Here are five particularly interesting investigations

Lost USB key from Employment and Social Development Canada reinforces lessons learned

An earlier investigation into a data breach involving ESDC was featured in an OPC special report tabled in Parliament on March 25, 2014, which noted that the organization did not translate its formal privacy and security policies for the protection of personal information into meaningful business practices.

The OPC investigation concluded that this was a major contributing factor resulting in the loss of a hard drive, which was noticed missing on November 5, 2012. The drive contained the personal information of 583,000 student loan recipients.

That same month, a USB key containing the personal information of 5,045 Canada Pension Plan Disability appellants disappeared from a desk in an ESDC office. As with the hard drive, the USB key was neither password-protected nor encrypted, nor was it ever found.

The missing personal information included each individual’s SIN, date of birth, surname, medical conditions, date of birth, education level, type of occupation and whether other payments were being received, such as worker’s compensation. In the wrong hands, such information could lead to identity theft or fraud.

An OPC investigation into the disappearance of the USB key found weaknesses in the same four types of privacy management controls considered in the student loan hard drive case; namely physical, technological, administrative and personnel controls.

This disappearance differed from the student loan hard drive case because a Justice Canada lawyer had custody of the USB key when it went missing. The lawyer was working from an office at ESDC to help triage the disability pension appeal cases pending a hearing before the former Review Tribunal. The lawyer had left the USB key lying on a desk in a locked office instead of storing it in a security cabinet.

More generally, our investigation found that the Justice department also failed to translate its security and privacy policies into meaningful business practices.

Both ESDC and Justice accepted OPC’s nine recommendations to better protect personal information under their control. Most of the recommendations echo those made in the hard drive case.

Wanted by the CBSA Program