Privacy Act Annual Report to Parliament 2010-11

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

Follow us on Twitter: @privacyprivee

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2011

Cat. No. IP50-2011

ISBN 978-1-100-52918-9

November 2011

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011. This tabling is pursuant to section 38 of the Privacy Act

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

November 2011

The Honourable Andrew Sheer, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Privacy Act for the period April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011. This tabling is pursuant to section 38 of the Privacy Act.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

About the Privacy Act

The Privacy Act, which took effect in 1983, obliges approximately 250 federal government departments and agencies to respect the privacy rights of individuals by limiting the collection, use and disclosure of their personal information.

The Privacy Act also gives individuals the right to request access to personal information about themselves that may be held by federal government organizations. If individuals feel that the information is incorrect or incomplete they also have the right under the Act to ask that it be corrected.

Commissioner’s Message

In the decade since 9/11, safety in the skies has come at a growing cost to privacy. In a wearisome modern ritual, we shed shoes and boots, and unzip our luggage to exhibit tiny toiletries in clear plastic bags. We “choose” whether to be patted down by a uniformed stranger, or to stand spread-eagled in a glass-enclosed scanner. We accept that our travel plans, passport numbers and other personal information are shared among airlines and governments.

We endure all this because we have no alternative if we wish to travel through Canadian airports. And, at the end of it all, we anticipate a significant payoff: a flight safe from terrorists and other threats.

From my perspective as Privacy Commissioner, however, that’s not the whole story. In addition to providing physical security, the state also has an obligation to treat individuals with respect — to preserve their dignity and to safeguard their personal information.

This is not a mere frill or a “nice-to-have”; it is fundamental to the trust relationship that must exist between citizens and their government.

This annual report takes a good hard look at the federal government’s stewardship of personal information — in the context of aviation security, law enforcement and day-to-day government operations.

While there is much to applaud, the record is not unblemished.

In an audit of airport security measures, for instance, we looked inside the private rooms where officers review images generated by full-body scanners and found a closed-circuit television camera and a cellphone. We did not find many such devices with recording capabilities — but nor did we find none, as the rules require.

We also found highly sensitive documents related to security incidents stored on open shelves and in boxes where passengers may be present.

Too much information

But of even greater concern to us was that security authorities were collecting more personal information than permitted under their mandate — on incidents that were not threats to air safety and that, in some cases, were not even illegal.

A separate audit of the RCMP’s control over its operational databases also raised concerns over the stewardship of personal information.

For example, when a person receives a pardon for a past crime, or is found to have been wrongfully convicted of an offence, the RCMP is supposed to block access to any information about the incident in its database. This hasn’t been happening, so even though people have a right to get on with their lives, information about their past can continue to be shared.

Without question, the state needs personal information to govern. No government could avert a terrorist attack, fight crime, issue a passport or administer the tax system without data about individuals.

Modern information technology facilitates the process. Data can be collected more rapidly and in greater quantity than ever before. It can also be processed, manipulated, transformed, stored and disclosed more readily than ever before.

The stated objective of all this data management is better program delivery, strengthened public safety, and more effective governance and accountability.

But, as this report describes, so much personal information in the hands of government can also pose risks to the privacy of individuals.

Privacy risks

For instance, it is none of the state’s business if a person travels in Canada with large sums of cash, yet such information is collected and shared among authorities. A wealthy traveller becomes a suspicious traveller.

A person’s criminal conviction is overturned and the police record ought to be sealed. Instead, the same erroneous information that led to the wrongful conviction can continue to circulate, potentially crippling careers and even lives.

One vocal critic of the government discovers that his sensitive medical information is included in a ministerial briefing binder and shared widely among officials with no reason to know about it.

Too much information can also lead to data spills. A troubling finding in this report is that the most preventable privacy invasions are often the result of simple human error — like the psychiatric nurse at a federal correctional institution who forgot a patient’s file on a city bus.

These are some of the reasons why the Privacy Act sets rules around the collection, use, storage, retention, safeguarding and disclosure of personal information. And this report is about the state’s stewardship of personal information under the Act in 2010-2011. It describes what the government is doing right, what it’s doing wrong, and how our Office worked to highlight opportunities for improvement.

Personal information is available today in unprecedented amounts, and the state’s appetite for it is voracious. The technology used to manage the data is powerful, yet at the same time also vulnerable.

In this uniquely challenging context, the Government of Canada is obliged to handle the personal information of Canadians with an uncompromising level of care.

Not some of the time, or even most of the time, but all of the time.

Our Office will continue to ensure it lives up to its obligations — and to the trust and expectations of Canadians.

Privacy by the Numbers — 2010-2011

| Received | |

|---|---|

| Linked to the Privacy Act | 1,944 |

| Linked to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) | 4,789 |

| Not linked exclusively to either Act | 2,188 |

| Total received | 8,921 |

| Closed | |

| Linked to the Privacy Act | 1,859 |

| Linked to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) | 4,762 |

| Not linked exclusively to either Act | 2,183 |

| Total received | 8,804 |

| Received | |

|---|---|

| Access | 328 |

| Time Limits | 251 |

| Privacy | 129 |

| Total received | 708 |

| Closed | |

| Through early resolution | |

| Access | 30 |

| Time Limits | 6 |

| Privacy | 42 |

| Total | 78 |

| Through investigation | |

| Access | 180 |

| Time Limits | 251 |

| Privacy | 59 |

| Total | 492 |

| Total closed | 570 |

| Received | 52 |

|---|---|

| Reviewed as high risk | 19 |

| Reviewed as lower risk | 68 |

| Total reviewed | 87 |

| Legal opinions | 16 |

|---|---|

| Litigation — decisions rendered | 0 |

| Litigation — cases settled | 2 |

| Draft bills and legislation reviewed for privacy implications | 19 |

|---|---|

| Public-sector policies or initiatives reviewed for privacy implications | 51 |

| Policy guidance documents issued | 16 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances on public-sector matters | 14 |

| Other interactions with Parliamentarians or staff | 34 |

| Public sector | |

|---|---|

| Visits by external stakeholders | 32 |

| Public events | 2 |

| Combined public and private sectors | |

| Speeches and presentations | 112 |

| News releases and communications tools | 57 |

| Exhibits and other offsite promotional activities | 20 |

| Publications distributed | 34,007 |

| Visits to principal OPC website | 2.22 million |

| Visits to OPC blogs and other websites | 1.01 million |

| New subscriptions to e-newsletter | 321 |

| Total subscriptions to e-newsletter | 1,013 |

| Requests received | 63 |

|---|---|

| Requests closed | 64 |

| Requests received | 105 |

|---|---|

| Requests closed | 106 |

Chapter 1: The Year in Review

Key Accomplishments in 2010-2011

Here are highlights of the work we did over the past fiscal year to strengthen and safeguard the privacy rights of Canadians in their dealings with the Government of Canada.

For details on any of these activities, please refer to the associated section numbers of this report, listed at the right.

Privacy Compliance Audits

| We conducted two audits during the year to test for compliance with the Privacy Act. | |

|---|---|

|

One examined whether the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) and the thousands of airport screeners it hires under contract respect the privacy of the travelling public and are good stewards of their personal information. It found that, while elements of a privacy management framework are in place, some significant gaps remain in practice. Of greatest concern is that the agency collects personal information beyond its statutory authority. For example, CATSA officers sometimes alert police when they encounter a traveller on a domestic flight carrying large sums of cash. It is legal to transport money within Canada, and, in any case, the matter is unrelated to aviation safety and therefore lies outside the agency’s mandate. We also found issues around the safekeeping of sensitive documents. For instance, incident reports turned up on open shelving units, on the floor and even in a room where passengers are taken for further screening. Moreover, despite being strictly prohibited, the audit discovered a cell phone and a closed-circuit TV camera in the rooms where officers view the images generated by full-body scanners. These issues were addressed promptly when brought to the attention of CATSA authorities. |

2.1 |

|

Our other audit looked at the RCMP’s management of operational databases that are widely shared with other police services and government institutions. One of the best known is CPIC, the Canadian Police Information Centre, which holds more than 10 million records and is accessed by approximately 80,000 law enforcement officers in more than 3,000 police departments, RCMP detachments, and federal and provincial agencies. While the RCMP has policies and procedures in place to safeguard this sensitive information, we also found some troubling gaps. For instance, with respect to a database called the Police Reporting and Occurrence System (PROS), the RCMP has no process to withhold access to any information that relates to an offence for which a pardon has been granted or — worse — that resulted in a wrongful conviction. The RCMP committed to addressing all of our concerns. |

2.2 |

|

We also followed up on three audits that we conducted in 2008 and 2009. We were advised by the responsible departments that 32 of the 34 recommendations we had made in those audits had been implemented, either entirely or to a substantial degree. |

4.4 |

|

One follow-up inquiry focused on the RCMP’s exempt databanks, which store personal data that is not subject to the access provisions of the Privacy Act. We were pleased to learn that the force had followed our recommendations to sift through the data, and purge any that should not be there. Indeed, by March 2011, all but 190 of the 5,288 files that had been in the RCMP’s national security exempt databank in March 2008 had been removed. Similarly, more than 58,000 criminal intelligence files were weeded out. |

2.5 |

Inquiries, Complaints and Data Breaches

|

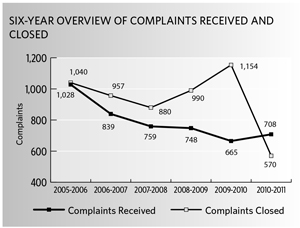

Our inquiries unit responded to 1,859 calls and letters related directly to the Privacy Act in 2010-2011, a 30-percent decline from the year before. We fielded a further 2,183 inquiries where the applicable privacy law could not be determined, or that pertained to neither of the two statutes. Since the number of visits to our Office website continues to rise — up since 2007-2008 by 31 percent, to 2.2 million visitors in 2010-2011 — we surmise that more people are going online to find answers to their privacy-related questions. |

5.1.1 |

|---|---|

|

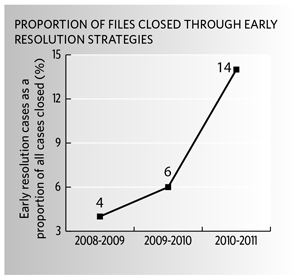

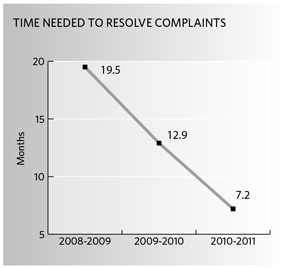

We continued this year to focus on early-resolution strategies, under which complaints are resolved without formal investigations. In all, 78 of the 570 complaints we closed last year were resolved in this way. This represented 14 percent of our caseload, up from six percent the year before. This has had a beneficial impact on the timeliness of our service. Early resolution cases were closed in an average of 3.6 months last year, bringing our overall treatment times down to 7.2 months, on average, from 12.9 months in 2009-2010. |

5.1.2 |

|

Of the 492 complaints that proceeded to full investigations in 2010-2011, the vast majority related to problems that people had in gaining access to their personal information in the hands of government (182), or to the time it took for the government to respond to their access requests (251). Nearly 80 percent of the time-limits complaints we investigated were lodged against the Correctional Service of Canada (150), the Canada Revenue Agency (24) or the Department of National Defence (23). We issued formal findings in 443 of our investigations, with the others being discontinued (41) or settled during the course of the investigation (8). In 63 percent of those findings we sided with the complainant, most often because the institution had not given the complainant timely access to his or her personal information. Where we did not substantiate a complaint, it was typically because the institution had properly applied one or more of the exemptions that allow it to withhold personal information under the Privacy Act. Of the 570 complaints we closed in all, 101 related to concerns about the collection, use, disclosure, retention or disposal of personal information. The circumstances ranged from the egregious to the banal. |

5.1.4 |

|

One noteworthy case involved Veterans Affairs Canada, where we learned that a large quantity of the complainant’s sensitive personal information, including medical information, had found its way into briefing notes prepared for the then-Minister of Veterans Affairs. In advance of the complainant’s participation in a Parliament Hill press conference, for instance, the Minister was briefed about the complainant’s medical history, recommended treatment plan, and the level of veteran’s benefits he received. The personal information was, moreover, widely shared among Departmental officials who would normally need little or no access to the man’s medical information in order to fulfill their duties. We upheld the complaint as well founded. As the investigation revealed serious systemic issues, we decided to launch a full audit of the Department in 2011-2012. |

3.1 |

|

Other privacy violations were far less glaring, but no doubt still troubling for the individuals involved. We found several instances in which the personal information of Canadians was mishandled by public employees — left exposed in public places, abandoned on a bus, or shipped through a prison’s internal mail system without benefit of an envelope. |

4.1.1 4.1.2 4.1.4 |

|

We also raised questions about the way Canada Post gauges the validity of requests for special paid leave to care for an ailing relative. We concluded that the organization asks for more information than necessary, including some about third parties. |

2.4.1 |

|

In addition to complaints from individuals, we received 64 reports from departments and agencies, detailing instances in which they had inappropriately disclosed the personal information of Canadians. Institutions are required by Treasury Board policy to report such data breaches to our Office in a timely manner, and more reports than ever reached us during the past fiscal year. Here again we found that many of the incidents were caused by sloppiness — binders left on public transit and airplanes, typos on address labels, and documents faxed to the wrong office. As in every other year, we once again discovered that the processing of requests under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act can lead to the inadvertent release of personal information that should have been protected. |

4.2 |

|

In one unusual incident, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada noted that its brand new online portal for Service Canada had a technical glitch that enabled users to view financial and other personal information of previous visitors to the site. An internal investigation concluded that only 75 of the 85,000 people who had used the site on its first day of operation had been affected by the technical failure. The probe traced the problem to a feature of the underlying architecture, called Access Key, and disabled the feature. The Department continued to work with Bell Canada, which provides the Access Key service for the government, to find a permanent and reliable technical solution. |

4.2.6 |

|

We also report this year on the disclosures that were made under section 8(2)(m) of the Privacy Act, which allows government departments and agencies to disclose personal information if it is clearly in the greater public interest, or clearly in the interests of the individual concerned. Typical examples included advising a community before an offender is released from prison, informing provincial health officials when airline passengers may have been exposed to a traveller with tuberculosis, or passing along warnings about professionals with disciplinary or other problems. |

4.5 |

Privacy Impact Assessment Reviews

|

We reviewed 87 Privacy Impact Assessments in 2010-2011, 19 of them in greater depth because of the significance of the privacy risk or the broader human rights or societal issues involved. Departments and agencies are required to submit such assessments to our Office to demonstrate that they have considered the privacy ramifications of proposed programs or activities, and planned for ways to mitigate intrusive impacts. |

2.3 |

|---|---|

|

One of our reviews examined a plan by the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority to observe passengers in the airport pre-boarding areas for suspicious behaviour. We expressed several concerns, including the potential for inappropriate risk profiling based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, age or gender. |

2.3.2 |

|

Another Privacy Impact Assessment we reviewed was submitted by Citizenship and Immigration Canada and related to the use of biometrics to identify all non-Canadians entering Canada. We made a number of recommendations to better safeguard the data and ensure it is shared with other nations only under the most stringently controlled circumstances. |

2.3.3 |

|

We also continued to review a series of Privacy Impact Assessments related to a large-scale and evolving project that enables the sharing of investigative information collected by the RCMP and provincial, territorial, aboriginal and municipal police forces — amongst themselves and with federal government departments. The data-sharing structure is called the National Integrated Interagency Information System, or N-III. Some of the information that can be accessed through this structure may be subjective, or indicate no wrongdoing at all. We noted that, if it is used without the appropriate context and safeguards, the information could result in detrimental outcomes for innocent individuals. We recommended safeguards and controls for this information sharing, as well as greater transparency and accountability. |

4.3 |

Policy and Parliamentary Affairs

|

We made 15 appearances before Parliamentary committees over the past fiscal year, and all but one of them dealt with public-sector issues. We weighed in on matters such as open government, child sexual exploitation and the long-form census. We outlined the priorities of the Office as Commissioner Stoddart’s leadership as Commissioner was renewed for another three years. Aviation security was an area of particular and ongoing concern, in light of legislative measures such as the Advance Passenger Information/Passenger Name Record program, the Passenger Protect Program, and America’s Secure Flight Program. These measures have resulted in the creation of massive government databases, the use of secretive no-fly lists, the increased scrutiny of travellers and airport workers, and greater information sharing with foreign governments. During our Parliamentary committee appearance on aviation security,we underscored the importance of transparency, minimizing data collection, setting limited retention periods, and establishing robust and accessible redress mechanisms. |

3.5 5.2 |

|---|---|

|

Another ongoing concern related to lawful access legislation, in which the government looks for ways to strengthen the capacity of police and security agencies to gain access to data associated with citizens’ electronic communications. Commissioner Stoddart joined with provincial and territorial counterparts to write to the Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada, outlining the privacy risks that they see emerging from the government’s intention to amend the legal regime governing the use of electronic search, seizure and surveillance. |

2.6.2 |

Supporting Public Servants

|

Canadians count on the government to handle their personal information with the utmost care and professionalism. But government isn’t a single monolithic entity; it’s tens of thousands of individuals who generally try their best to live up to the requirements of the Privacy Act. Recognizing the challenge for public servants operating under extraordinary pressure to collect and manipulate data, we sought in 2010-2011 to provide practical assistance through workshops, seminars and other outreach activities. In March, for instance, we hosted our inaugural Privacy Practices Forum, an opportunity for civil servants to learn and share knowledge about ways to advance privacy in their respective departments. |

5.3 |

|---|---|

|

We also invested a great deal of effort over the past year in helping institutions adapt to a new government Directive on the completion of Privacy Impact Assessments. We held a second annual workshop to guide more than 100 participants in the preparation of solid Privacy Impact Assessments. During the workshop, we launched a detailed guidance document that sets out what we expect from such assessments. Entitled Expectations: A Guide for Submitting Privacy Impact Assessments to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, the document was distributed across the public service and is available on our website. |

5.3.1 |

|

Our Office also drew on the advice of a wide spectrum of experts in both privacy and security to develop a reference document to help policymakers, practitioners and citizens integrate privacy protections with new public safety and national security objectives. Entitled A Matter of Trust: Integrating Privacy and Public Safety in the 21st Century, the document provides important context, as well as step-by-step guidance on achieving the appropriate balance. |

2.6.1 |

|

Another area where we offered our guidance related to the increasing use of biometric information, such as fingerprints and facial images. Biometric systems can contribute to highly reliable and robust identification systems, but can also raise significant privacy challenges, including the covert collection of biometric characteristics, cross-matching, and the unwanted disclosure of secondary information embedded in an individual’s biometric information. To help institutions weigh the pros and cons, our Office prepared a detailed primer called Data at Your Fingertips: Biometrics and the Challenges to Privacy. It introduces a method for determining the appropriateness of biometrics for different applications, and makes recommendations for privacy-sensitive designs. |

2.7 |

Advancing Knowledge

|

The Privacy Act affords us no explicit public education mandate, but that doesn’t stop us from reaching out to the people we serve to help them better understand their privacy rights and how to protect their personal information. In the past year, for instance, we participated in 20 exhibits and other offsite promotional activities, distributed 34,000 publications, delivered 112 speeches, and hosted 32 stakeholder visits. Our websites and Office blogs remain popular vehicles for the dissemination of information, with 3.23 million distinct visits over the past fiscal year. |

Privacy by the Numbers |

|---|---|

|

We are also working hard to advance the state of knowledge about privacy and the emerging threats to personal information. Toward that end we commissioned research on such matters as key issues of concern for officials in access-to-information and privacy branches of federal institutions; privacy and data-collection laws and practices in developing countries; and the privacy impact of new technologies for authenticating identity in online payment systems. |

5.5.1 |

Chapter 2: Data Diet

Can the State Curb its Appetite for Information about its Citizens?

Asked in 1924 why he felt compelled to scale Mount Everest, British climber George Mallory is famously reported to have quipped: “Because it’s there.”

The same logic appears to be driving many organizations the world over as they rush to scoop up veritable mountains of personal information. Information is power, so wouldn’t it be a shame to leave any byte unclaimed? Data, it seems, is good; more of it still better.

The Government of Canada, already the nation’s single biggest repository of personal information, is not immune to this impulse. Personal data is the oxygen that the state needs to govern. Without it there can be neither revenues nor entitlements; no peace, order or good government.

And yet, there are limits. Sections 4 to 6 of the Privacy Act specify the terms under which federal departments and agencies may collect, retain and dispose of personal information.

In general, the government can only collect personal information if it relates directly to an operating program or activity. Wherever possible, the data should be collected from the individual to whom it relates. With some specific exceptions, the individual should be informed about the purpose of the collection.

Once the information was used for its intended purpose, there are limits to how long it can be retained, and rules for how it must be disposed of.

Minimizing collection

Without a doubt, the digital era has made it far easier for organizations to collect everything, rather than to sift, sort, and jettison what’s no longer needed.

But ease and convenience are no justification for the excessive collection or retention of personal information. Indeed, the statutory limitations set out in the Privacy Act have both a practical and a philosophical rationale.

Curbing the volume of personal data in the hands of government lessens the chances of accidental disclosures, and of errors or omissions that can lead to wrongheaded decisions, often with dire consequences for the affected individual.

Moreover, people have a fundamental right to live their lives in peace and anonymity, free from the prying eyes of the state. This is the foundation for the trust that must exist between citizens and their government, an expression of the social contract that defines an enlightened nation.

This chapter explores what we learned in 2010-2011 about the government’s stewardship of personal information, including its collection, retention, secure storage and disposal. It includes the following sections:

- 2.1 Audit of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- 2.2 Audit of selected RCMP operational databases

- 2.3 Privacy Impact Assessments involving the collection of personal information

- 2.4 Complaint investigations involving the collection of personal information

- 2.5 Follow-up of our 2008 RCMP exempt databanks audit

- 2.6 Integrating privacy into public safety initiatives

- 2.7 Biometrics primer

2.1 Audit of the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

About the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

Established as a Crown corporation in April 2002 in response to the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, CATSA’s mandate is to screen passengers, flight crews, baggage handlers and maintenance staff for prohibited items.

CATSA reports that as of March 31, 2010 it had 530 employees and 6,790 contract personnel serving as screening officers. In an average year, they screen 48 million passengers and 62 million pieces of luggage at 89 Canadian airports.Footnote 1

Every year, tens of millions of travellers pass through Canadian airports. As a condition for boarding a flight, they and their baggage must undergo some form of security screening measures.

It is widely accepted that screening contributes to passenger safety, and our Office does not dispute this. We do, however, believe that security and privacy are not opposing values; an increase in one does not necessitate a loss of the other.

On the contrary: We take the view that a strong framework of control over the management of the personal information of passengers will mitigate privacy risks while, at the same time, also strengthening aviation security.

That is the context in which we examined whether the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA), the federal organization charged with screening passengers and luggage, complies with the information-handling requirements of the Privacy Act.

What we found

2.1.1 Full-body scanners

Full-body image scanners, present in many Canadian airports, detect concealed explosives or weapons through a traveller’s clothing.

CATSA has implemented a strong framework to protect passengers’ privacy. It includes controls to ensure that an image cannot be linked to a name or any other identifiable information about the passenger. Scanned images are sent electronically to a remote viewing room to ensure that the screening officer cannot view or identify the passenger. The images, moreover, cannot be retained or printed, and are permanently deleted once the passenger has been screened.

We did, however, find that procedures to protect privacy are not consistently followed. For example, the image-viewing officer is supposed to ensure that images are cleared from the screen before anyone enters or leaves the room. We observed instances where this did not happen.

We also witnessed an official inside the image-viewing room with a cellphone, which is strictly prohibited because such devices often have video-recording capabilities.

Further, we located a closed-circuit television camera in the ceiling above the viewing room at one airport. The camera was disabled after we brought the matter to CATSA’s attention.

Given the privacy concerns surrounding the use of full-body imaging technology, we recommended that CATSA ensure that privacy safeguards are understood, enforced, and subject to ongoing compliance monitoring. We also recommended a physical inspection of all viewing rooms and the disabling of any closed-circuit television cameras.

2.1.2 Collection of personal information

CATSA’s governing regulations and related orders require the organization to notify authorities if its screening activities detect a threat to aviation safety. It therefore quite properly collects the personal information of travellers found to be carrying a concealed weapon, explosive, incendiary device or other threat to aviation security, so that the incident can be reported to the appropriate authorities.

Potentially illicit activities

There are also occasions when a search for aviation threats inadvertently turns up evidence of other activities, such as an apparent attempt to import narcotics or to export large sums of money. While the smuggling of drugs or money is illegal, it is not a direct threat to aviation safety.

In such circumstances, CATSA’s practice is to detain the suspect and to alert the appropriate police or other law enforcement authorities.

However, we also determined that once local law-enforcement authorities have been called, CATSA’s involvement in the incident ends. Thus, CATSA’s practice of writing up incident reports on illicit activities that pose no direct threat to aviation safety is inappropriate.

Accordingly, we recommended that the organization restrict its collection of personal information to aviation security incidents.

Domestic transport of cash

We also found that CATSA collects personal information about domestic travellers carrying large sums of cash, and passes this along to police once the passenger has left the screening area.

It is not an offence to travel within Canada with large amounts of money. By permitting the individual to proceed through screening, it is evident that the cash does not constitute a threat to aviation security, which places it outside CATSA’s mandate.

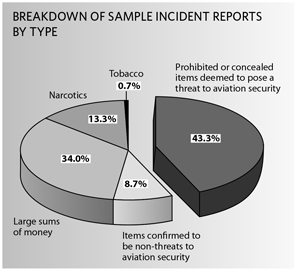

We were told that CATSA has more than 10,400 incident reports on file. We extracted an exploratory sample of 150 reports for examination. As shown in the chart, approximately 57 percent of the reports concerned matters unrelated to aviation security.

On the basis of our analysis, we concluded that CATSA is collecting personal information beyond its legislative mandate. Mindful of the size of our audit sample, however, we cannot determine the extent to which CATSA’s information holdings contain reports that should not be there.

We recommended that CATSA implement measures to ensure it collects only personal information that is directly related to aviation security.

2.1.3 Electronic boarding pass authentication system

As part of its pre-boarding activities, CATSA must verify the authenticity of boarding passes. A Boarding Pass Security System was introduced in 2009 to facilitate this process. It captures information printed on the boarding pass, as well as other data, in a special bar code.

While there may be a need to temporarily display the contents of the boarding pass bar code so that the screening officer can match the information with what is printed on the boarding pass, we questioned the necessity of collecting and retaining personally identifiable information in the system’s database.

Indeed, while the system was implemented to detect fraudulent boarding passes, CATSA is using the data (specifically passenger names) for other purposes. These include responding to passenger claims and complaints, as well as security incidents and breaches (for example if a person enters a restricted area without having been screened).

As a general rule, passengers’ personal information should not be collected on the basis that it may have some future use. CATSA was able to demonstrate that the collection of personal information derived from a boarding pass and bar code is necessary to fulfill it’s aviation security mandate. However, passengers are not informed that the data was being retained for 30 days, or that the information may be shared with CATSA’s foreign counterparts to address matters relating to aviation security.

We urged CATSA to more clearly inform passengers of the purposes for which the data is collected, the uses that are made of it, with whom and under what circumstances the information may be shared, and how long it is kept.

2.1.4 Disclosure of personal information

Disclosure to authorities

CATSA is obliged to report aviation security incidents to specific authorities, including the Minister of Transport, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), or the appropriate air carrier, police service or airport authority.

CATSA is not empowered to search for contraband. However, it will contact authorities when illegal narcotics or large sums of money are discovered during the screening process, and share the passenger’s name, flight information and a description of the alleged contraband.

We considered whether CATSA has the authority to contact the police or the CBSA about incidents that are unrelated to aviation security. For the purposes of the Privacy Act, the authority rests on whether such disclosures can be considered “a use consistent with the purpose” for which the information was obtained.

Under its mandate, CATSA obtains personal information for the purpose of screening individuals and their baggage for prohibited items and threats to aviation security. At times, officers stumble upon other kinds of illicit items, such as street drugs or smuggled money.

Determining whether disclosing information about such discoveries to the police or other authorities is a consistent use under the Act turns on whether individuals can reasonably expect CATSA to notify somebody when, in the course of carrying out their mandated duties, officers stumble upon illicit items outside of this mandate.

In our view, it is reasonable for an individual to expect that CATSA would notify the appropriate authorities when apparently illegal items are inadvertently discovered. While individuals are only consenting to a search of their person and baggage for threats to aviation safety, it would be unreasonable to expect that clear evidence of other illegal items would be ignored.

Indeed, passing such information to police ties directly to the original purpose for which the information was obtained — for public safety and compliance with the law in the context of aviation security. By contrast, as explained in section 2.1.2, it is not an offence to travel within Canada with large amounts of cash. Therefore, there is no reason why CATSA would need to alert authorities if it finds such cash during its screening activities.

To bring its disclosure practices into compliance with the Privacy Act, we recommended that CATSA stop notifying police when it discovers a large sum of money in the baggage of a person travelling domestically.

Disclosure to air carriers

Aside from informing police about incidents unrelated to aviation security, we also found that CATSA conveys personal information to airline carriers. This may not always be appropriate.

For instance, while it may be appropriate to notify an airline if a passenger will be delayed at the security checkpoint, there is no need to disclose specifics, such as contraband having turned up in the individual’s baggage.

We called on CATSA to ensure that all disclosures to airline carriers are limited to that which is necessary in the circumstances of each case.

2.1.5 Information protection at airports

CATSA has outsourced passenger screening to 11 private sector companies. Each contract includes a confidentiality agreement, which establishes the contractor’s obligations for safeguarding passenger information.

During our site visits to airports, however, we found deficiencies in this regard. We observed incident reports on open shelving units, on the floor, and in cabinets that did not meet required security specifications. At one airport we found reports stored in boxes in a room used to conduct private searches on passengers.

The confidentiality agreement requires screening contractors to protect records in accordance with CATSA’s Document Protection Procedures, which outline the storage and transmission requirements for information designated either ‘protected’ or ‘secret’.

The agreement states that CATSA will identify all information falling within either of the two categories. CATSA had not, however, done so at the time of our audit, which could have contributed to some of the storage deficiencies we observed.

We recommended that CATSA apply a security designation to personal information that is commensurate with the sensitivity of the information. Screening contractors should implement physical security measures that comply with Treasury Board standards.

We also found that CATSA does not systematically inspect or audit contractors’ handling of passenger information. The organization has been guided by the assumption that screening contractors are managing information appropriately, but with no assurance that this is so.

In the absence of an effective monitoring regime, contractors may circumvent their privacy obligations without consequence.

We recommended that CATSA ensure that screening contractors’ management of passengers’ personal information is subject to regular inspection and audit.

2.1.6 Retention and disposal of personal information by CATSA

In the event of a security incident or breach, CATSA typically collects the passenger’s name, flight information, address, phone number and a summary of the event. The report is faxed to CATSA’s Security Operations Centre in Ottawa and then entered into the Call and Incident Data Collection System, the electronic repository for security incidentreports.

Federal institutions are required by law to develop retention and disposal schedules to manage their records. These schedules establish how long records will be kept before they are destroyed or transferred to the control of Library and Archives Canada. A records retention and disposal schedule is important from a privacy perspective because holding on to records for too long may result in prejudice against the individual concerned.

We found that CATSA had not developed a retention and disposal schedule for personal information under its control. As a result, security incident reports were held at CATSA’s head office indefinitely.

We recommended that CATSA permanently delete all electronic and hard copy records that it does not have the authority to collect. These would, for instance, relate to the incidental discovery of contraband, items that were wrongly identified as threats to aviation security, and large sums of money carried by passengers.

CATSA should also establish a records retention and disposal schedule for personal information collected under its aviation security mandate.

2.1.7 Retention and disposal of personal information by contractors

Sample of document still legible after shredding

CATSA’s contracts with screening providers are silent on disposal requirements, leaving it up to screening contractors to develop and manage the process. We learned that incident reports are typically held for one year, then destroyed in on-site shredders or by private sector shredding companies.

We collected a sample of shredded material at one of the airports that handled its own document shredding. We found the papers were not destroyed according to the standard set by Treasury Board. While there is insufficient evidence to suggest a systemic problem, it does underscore the importance of monitoring disposal practices.

However, we found that CATSA has no audit protocol under which it can monitor records destruction by off-site shredding services. Consequently, there is no assurance that individuals who handle the personal information of passengers are screened to the appropriate security level, that incident reports are destroyed in a way that they cannot be reconstructed, and that records are disposed of in a timely fashion that mitigates the risk of unauthorized access.

We recommended that CATSA ensure that all contracts for the disposal of personal information comply with Treasury Board requirements and implement a protocol for monitoring off-site destruction practices.

2.1.8 Other safeguards are in place

Our audit revealed that other important safeguards are in place to protect personal information. Notably:

- CATSA’s head office is controlled by various measures, including security guards, closed-circuit television cameras and an intrusion detection alarm system. Electronic access control cards, biometric identifiers and security cabinets restrict access to the premises and records. We found no evidence to suggest that personal information could be compromised through inadequate physical security controls.

- CATSA operates a private network that connects its head office, airports and data centres. We reviewed the network architecture and found adequate measures to protect personal information. These included firewalls, intrusion detection and prevention technologies, automated software patch management, and access controls. Threat and risk assessments have been completed and annual penetration tests are performed to identify and remedy potential weaknesses.

- We found that data extracted from a boarding pass bar code is transmitted by a secure network to a local server, and then to a central database. CATSA has implemented controls to protect data in transmission. Moreover, personal information stored in the database is encrypted.

- Third-party service agreements include sound privacy provisions. For instance, personal information must be stored in Canada; security and physical measures must accord with Government of Canada security standards; information cannot be used for secondary purposes; and any individual with access to the database must have a secret security clearance.

- CATSA has installed closed-circuit television to observe and record passengers from the time they enter the screening waiting line until they have been processed by screening officers. We found that there are appropriate controls over access to, use, retention and disclosure of the video footage. Indeed, CATSA told us it will not release a copy of the footage unless compelled to by a warrant or court order.

2.1.9 Transparency

Federal institutions are obliged to describe their personal information holdings in Info Source, an index published by the Treasury Board Secretariat. However, we found that the current edition of Info Source is silent on CATSA’s collection of passenger information.

We also found a lack of transparency about the use of closed-circuit television in passenger screening areas. Only four of the eight airports we visited had signage visible to passengers, and it only stated that the area may be monitored. We confirmed that the cameras continuously record passenger movement.

We also observed that passengers were not always informed of their options when subjected to a physical search.

Passengers referred for supplementary screening have the option of a full-body image scan, a physical pat down in public view, or a physical pat down in a private area such as a partitioned stall or separate room. However, in observations at five airports, we found that travellers were typically asked to choose between a full-body scan and a pat down in public view; the option of a hand search in private was seldom offered.

We recommended that CATSA describe all categories of personal information under its control in the next edition of Info Source.

In the spirit of transparency, the organization should also ensure that passengers are advised that they are being monitored by closed-circuit television and that there are three options for secondary physical searches.

2.2 Audit of Selected RCMP Operational Databases

2.2.1 Overview

Canada’s law enforcement and criminal justice community relies on an extensive network of database systems to help enforce laws, prevent and investigate crime, and maintain peace, order and security.

For the purposes of our audit we looked at two of several databases that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) uses for its policing and crime-prevention operations. Both share information with a broad range of public safety partners.

About the Mounties

With approximately 30,000 employees, the RCMP enforces federal laws across Canada and provides investigative and operational support services to more than 500 Canadian law enforcement and criminal justice agencies. It also provides policing services in all provinces except Ontario and Quebec, as well as in the three northern territories and nearly 200 municipalities.

- The Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) offers computerized storage and retrieval of information on crimes and criminals. CPIC holds more than 10 million records that relate, for example, to driver’s licences and vehicle plates, stolen vehicles and boats, warrants for arrest, missing persons and property, criminal history records, fingerprints, firearms registration, and missing children.

More than 80,000 law enforcement officers in more than 3,000 police departments, RCMP detachments and federal and provincial agencies can connect to the central computer system through CPIC. Courts, parole boards and government departments and agencies, such as the Correctional Service of Canada, the Canada Border Services Agency, Canada Revenue Agency and Passport Canada, also use CPIC.

Information contained in CPIC is shared internationally via INTERPOL, and with American law enforcement agencies such as U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Even the Insurance Bureau of Canada, the national industry association for the property and casualty insurance market, has access to CPIC.

CPIC processed more than 200 million queries through 40,000 access points in 2009. - The Police Reporting and Occurrence System (PROS) is the RCMP’s operational records management system. Introduced in 2003, PROS is used by the RCMP and 23 police partner agencies, typically those with fewer than 300 officers that do not have their own electronic records management system.

PROS contains information on any individual who has come into contact with police, whether as a suspect, victim, witness or offender, from initial occurrence to the final disposition of the case. About 1.6 million occurrence files are processed every year.

Under powers vested in our Office through the Privacy Act, we audited the RCMP’s compliance with the Act’s requirements on the collection, protection, retention and disposal of personal information in CPIC and PROS.

How the systems are used

An RCMP officer stops a car for speeding. She then uses her in-car computer to run a query in CPIC to see whether the detained vehicle is stolen or whether there are outstanding warrants on the driver. The officer might then search PROS, in case the vehicle or driver has been involved in prior incidents. An occurrence record is created in PROS to record the event. The record is subsequently updated as the case develops.

In particular, we examined:

- the RCMP’s policies and procedures governing access to and use of CPIC

- policies and procedures related to the removal of personal information contained in PROS that is no longer required

- the RCMP’s practices for reviewing compliance with the terms and conditions of use for both CPIC and PROS and

- the management of user access to PROS.

We did not examine how the personal information contained in these databases is actually used. Nor did we look at the data-protection safeguards applied by municipal, provincial, territorial and international partners who have access to the data through formal information-sharing arrangements.

2.2.2 Why this issue is important

Both CPIC and PROS contain extensive amounts of sensitive personal information that, if improperly used or disclosed, could have significant impacts on the reputation, employability and personal safety of affected individuals. A security breach could also compromise ongoing police investigations.

The RCMP reports annually on security breaches of the CPIC system. Some of these breaches have involved unauthorized access to, or inappropriate use of, the personal information of others.

The RCMP has also found that certain police agencies contravened CPIC policy by disseminating to employers the details of convictions, discharges or pardons of a prospective employee, without the informed consent of the individual.

The RCMP is responsible for the storage, retrieval and communication of shared operational police information on behalf of accredited criminal justice and other partner agencies. It has an obligation to protect the privacy of individuals with respect to the personal information in its care.

2.2.3 What we found

Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC)

-

Policies and procedures

The RCMP has policies and procedures in place to govern access to and use of data in the CPIC database in a way that protects the personal information of Canadians. Among other things, the risk-mitigation strategy for information technology requires agencies to implement strong identification and authentication protocols to ensure that all users are legitimate.

However, we found that one-third of agencies had constraints on their technical infrastructure that impeded them from putting such protocols in place.

We also looked at the Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) that the RCMP uses to set out the terms under which agencies may use the CPIC database. MOUs were in place with agencies that had limited law-enforcement powers, or roles that are complementary to law enforcement.

However, at the time of our audit, MOUs had yet to be signed with approximately 25 percent of police agencies that had previously been granted access on the basis of their core policing role.

We recommended that the Canadian Police Information Centre set clear timeframes to establish MOUs containing privacy provisions with any entities where such agreements do not already exist.

-

Breaches

Our audit established that privacy breaches have occurred but are relatively rare. Mechanisms are in place to investigate them and to act on the results of those investigations.

Many of the breaches involved people querying CPIC for personal reasons. The RCMP also recently discovered that certain police agencies were passing criminal record information from the CPIC system to employers. The data related to convictions, discharges or pardons, and was disseminated without the informed consent of the prospective employee.

Depending on their severity, data breaches can lead to a directive from the RCMP, a change in CPIC policy, a reprimand, a suspension, or a dismissal.

Police Reporting and Occurrence System (PROS)

-

Information purging

Legislation requires that all records created in PROS be purged when the retention period for each category of information has expired. Unless records are purged, they remain readily accessible.

Prior to deletion, records are evaluated to determine whether they should be archived with Library and Archives Canada. We found that the PROS database was designed to automatically purge occurrences once they reach their disposition date, unless they have archival value.

But while the functionality to purge exists, we found that the RCMP has disabled it in order to extract some statistical information.

An organization that retains personal information longer than required is in contravention of the Privacy Act. We therefore recommended that the RCMP purge the data necessary to bring it into compliance with the Act.

The RCMP responded that it assigned staff to develop a statistical solution and, once implemented, the appropriate data will be purged as required by legislation.

While examining purging procedures mandated by law, we also found that the RCMP had not yet implemented processes to remove access to records related either to pardoned offences or wrongful convictions. In the event of a pardon or a wrongful conviction, the related records are supposed to be sequestered and should no longer be accessible in PROS.

It is important to Canadians who have received a pardon that the information not be inappropriately disclosed so they can enjoy the same opportunities to get a job, travel, study and volunteer as any other Canadian. The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination based on a pardoned criminal record. Such freedom from discrimination is doubly important if a person has been wrongfully convicted.

To mitigate the risk of an unlawful or inappropriate disclosure, we recommended that the RCMP implement processes to remove access to records in the PROS database that relate to pardoned offences and wrongful convictions.

-

User access and activity

RCMP policy requires that a user’s access to PROS be revoked when access is no longer required for the user’s job function, or if the user has not accessed the system for 14 months.

The RCMP was, however, unable to demonstrate that it systematically reviews PROS use to ensure it accords with governing policies.

Indeed, we found that there is no active monitoring of PROS user accounts and activity. We noted that there were more than 1,000 accredited users who had not accessed PROS in 14 months or more.

We also found that PROS is technically able to track a user’s actions in audit logs. The information records details on which records were viewed and any modifications made.

However, the RCMP informed us that, if misuse by a user is suspected, the level of effort required to consolidate and review the audit logs limits the ability to investigate. While an automated audit log review tool is available within PROS, it has not been implemented to date. As a result, it is highly labour-intensive to extract any details of a user’s activity, and thus to investigate potential misuse.

We recommended that the RCMP regularly review the status of PROS user accounts, and disable access when it is no longer required for users to perform their jobs.

In order to aid in the investigation of unauthorized access to personal information stored in PROS, we further recommended that the RCMP enable the audit log review tool.

-

Compliance audits

We found that the RCMP has Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with all partner agencies to ensure that the data in PROS is used only for legitimate law enforcement purposes.

The MOUs, which remain in effect for five years unless terminated for cause, give the RCMP the power to monitor the use of its networks and specific employee use, and periodically to conduct on-site visits to police partner agencies.

The RCMP was unable to demonstrate, however, that it systematically engages this power to ensure that police partner agencies are using the personal information contained in PROS in accordance with the governing terms and conditions of the MOUs.

Indeed, few audits have occurred. While all police partner agencies in Alberta have been audited, for instance, the same was true for only a handful in Nova Scotia and none at all in Prince Edward Island.

We recommended that the RCMP adopt a consistent and regular review process to ensure that all users are complying with the policies and procedures governing the use of the personal information in PROS.

The RCMP committed to addressing all the concerns raised in our audit.

2.3 Privacy Impact Assessments Involving the Collection of Personal Information

2.3.1 Overview

Privacy Impact Assessments are important tools to help federal institutions examine the privacy effects of new or significantly modified programs or activities.

One reason that Privacy Impact Assessments are so valuable is that they encourage government institutions to consider the privacy impacts of proposed initiatives early in the development process.

Optimally, the Privacy Impact Assessment process should help government institutions justify privacy-invasive programs and activities against a four-part test: Is the project absolutely necessary? Is it likely to be effective in achieving its objectives? Is the project’s anticipated infringement on privacy proportionate to any potential benefit to be derived? And are less intrusive alternatives available?

When the four-part test has been met, government institutions must still demonstrate that the information that was collected will be protected. We therefore also encourage proponents to consider the 10 internationally acceptable fair information principles for the stewardship of personal information. Among other things, these principles call for data collection that is minimized and appropriate, and for mechanisms to ensure it is secure, so as to lower the risk of future privacy invasions.

New Directive

On April 1, 2010 the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Directive on Privacy Impact Assessment replaced the Privacy Impact Assessment Policy that had been put in place in 2002. While the Directive differs somewhat from the earlier Policy, federal institutions are still required to conduct Privacy Impact Assessments early in the development of initiatives that pose threats to privacy, and to submit them to our Office.

While we read and assess all files we receive, we conduct more in-depth reviews where, in our view, programs or activities pose significant privacy risks or raise broader human rights or societal privacy issues. For these, we provide departments with detailed recommendations, and follow up to ensure risks have been mitigated.

We do not approve assessments or endorse any projects or proposals during our reviews. Our recommendations and advice on how projects can be improved are intended to better safeguard the privacy of Canadians. While institutions are not obliged to heed our advice or implement our recommendations, we do find that most are open to our input and work with us to resolve or mitigate privacy concerns.

We received 52 Privacy Impact Assessments during the past fiscal year, down significantly from the 102 submissions we received the year before. The reason for this decrease is not clear; it could be that institutions are taking time to implement new procedures under the new Directive. It is also possible that the spike in submissions in 2009-2010 was due to institutions completing Privacy Impact Assessments under the old Policy.

We applied a triage process in order to focus our resources on files of the highest priority. Thus, we reviewed 19 files that we determined related to projects posing the highest risk to privacy. Another 68 lower-risk files were also examined.

You will find below descriptions of several initiatives for which we reviewed Privacy Impact Assessments over the past fiscal year, along with summaries of our advice and any continuing concerns.

The review process is intended to be iterative and evergreen, so we often review and offer guidance on several versions of Privacy Impact Assessments as initiatives mature from inception to implementation.

2.3.2 Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

Passenger Behaviour Observation Program

We received a preliminary Privacy Impact Assessment from the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) for the Passenger Behaviour Observation (PBO) Pilot Project.

PBO is an airport screening measure in which passengers in the pre-boarding security screening lineup are observed for suspicious activity.

PBO-trained CATSA officers may approach passengers and engage them in a brief conversation, and ask to see their identification and travel documents. Depending on the outcome of the conversation, passengers may be directed to secondary screening.

Following each interaction, PBO officers fill out a case card, which describes the incident and the passenger’s appearance, but contains no personally identifying information such as names or addresses.

Our concerns

In reviewing CATSA’s Privacy Impact Assessment, we were concerned about the effectiveness of this initiative in identifying threats to aviation security. We questioned its necessity, in light of the many other security procedures and programs already in place.

In particular, we noted the potential for inappropriate risk profiling, based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, age or gender.

We also commented that CATSA appears to be moving towards identity-based screening, representing a significant shift in operations that have previously focused on screening for objects posing a risk to aviation security.

We were further concerned that the details of the PBO pilot were authorized by an Interim Order under the Aeronautics Act, rather than prescribed by regulation. Under the Act, the Minister of Transport may issue interim orders if immediate action is required to deal with a serious threat or a significant risk to aviation security. These orders are made without Parliamentary debate or other public input. It does not seem to us that an ongoing program such as PBO falls into this category.

Our recommendation

We recommended that initiatives such as PBO be authorized by regulation rather than through interim orders. Regulations are published in the Canada Gazette for public scrutiny and comment. We feel this would promote a more open and transparent process, and lead to better scrutiny of a potentially privacy-intrusive measure.

In the meantime, CATSA has posted signs to notify passengers that they may have to show identification at screening checkpoints, and has assured us that interactions with passengers in the screening line are conducted as discreetly as possible. CATSA also invited our staff to visit the pilot project at the Vancouver International Airport in June 2011 to more fully assess the program.

2.3.3 Citizenship and Immigration Canada

Five Country Conference High Value Data Sharing Protocol and Temporary Resident Biometrics Project

The Government of Canada is moving towards the use of biometrics to identify all non-Canadians entering Canada. The initial focus is on people who are required to get visas as visitors, students or temporary workers, as well as on refugee claimants and immigration enforcement cases.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada has asked us for privacy advice on two initiatives involving the collection and use of biometric identifiers, such as fingerprints and digital photographs, for immigration controls. The initiatives involve the Department, the Canada Border Services Agency and the RCMP.

- Under the Five Country Conference High Value Data Sharing Protocol, biometric information required for immigration screening is shared between Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States.

- Under the Temporary Resident Biometrics Project, scheduled for a phased rollout in 2013, visitors, temporary foreign workers and students applying for visas will be required to enroll abroad with 10 fingerprints and a digital photo. This data will be checked against the enrolled template when the individual arrives at a port of entry to Canada.

Our recommendations

With respect to both initiatives, we called on Citizenship and Immigration Canada to ensure that:

- the use of biometrics is both necessary and effective in detecting and preventing fraud;

- sharing of this sensitive information, particularly for vulnerable individuals such as refugee claimants, be undertaken with caution and under strict safeguards and protocols;

- particular attention be paid to safeguarding fingerprints, photos and foundation documents collected by private sector Visa Enrollment Centres abroad; and

- the criteria for sharing biometric information with other nations be developed carefully and limited to the most serious cases.

2.3.4 Public Service Commission

Political Impartiality Monitoring Approach

In last year’s annual report, we discussed our concerns about the Public Service Commission’s Privacy Impact Assessment for a program that would cross-reference government databases of current and former public servants with candidate lists in federal, provincial and municipal election campaigns.

According to the information we received, the Political Impartiality Monitoring Approach was also intended to monitor the Internet, including media outlets, personal websites, and social networking sites such as Facebook, for signs of potentially inappropriate political activity by public servants.

Since that report, the Commission advised us that the initiative was never fully developed or implemented, and that it has been dropped.

2.4 Complaint Investigations Involving the Collection of Personal Information

2.4.1 Canada Post demands too much information for leave requests

An individual filed a complaint over Canada Post’s collection of personal information in connection with two separate applications she made for special paid leave to take care of an ailing relative.

The application form is actually intended only to guide supervisors in weighing whether to grant a request for leave. Supervisors have some discretion in how many of the questions they actually ask. In this instance, however, the complainant’s supervisor erroneously gave the complete form to the complainant herself to fill out.

The form required extensive amounts of personal information about the requester, the ill person and even third parties. For example, it asked whether any other Canada Post employee had asked for leave to take care of the same patient.

As we investigated this complaint, Canada Post told us that the Crown corporation receives about 3,000 special leave requests every year, totalling more than 125,000 hours of work.

Over the years, arbitration rulings under the union’s collective agreement have helped shape how this category of leave is administered. Those decisions now require Canada Post to collect substantial amounts of information, in order to ensure that leave requests are considered in a fair and reasonable manner.

At the same time, Canada Post is concerned about preventing fraud or misuse of this open-ended leave provision. While acknowledging the organization’s duty in that regard, we nevertheless felt that too much personal data is being collected. We were particularly concerned about questions that require a leave applicant to furnish personal information about another person.

We concluded that the complainant had been asked for more personal information than was necessary to establish her entitlement to the leave, and upheld her complaint as well founded.

We also recommended a series of measures that Canada Post could take to address privacy concerns.

The organization accepted some of the recommendations, agreeing to collect only the personal information that is absolutely necessary for the proper administration of the program. Canada Post stated, for instance, that it would no longer require the names of other individuals (third parties) who might have been involved in caring for the sick person.

The organization also agreed to update its written procedural guidelines that supervisors must follow when an employee requests a leave, in order to ensure that only required information is collected.

However, the organization insisted on continuing to collect information on other family members working at Canada Post, in order to ensure that two or more employees were not abusing the benefit by requesting the same leave.

In the absence of proof of extensive abuse, we continue to have reservations about this data collection. We have encouraged the organization to find less privacy intrusive ways to address its concerns about fraud in weighing leave requests.

2.4.2 Driver’s licence suitable ID for postal box rental

An individual complained after Canada Post required him to supply his driver’s licence number in order to terminate the rental of his postal box.

Canada Post countered that it requires box renters to furnish personal identification in order to ensure that a box is not being used or closed fraudulently. The postal service also stated that it has used such recorded ID to investigate cases where illegal goods may have been shipped to rented mailboxes.

Our investigation determined that Canada Post has a statutory obligation to provide a secure postal service, and was collecting and using personal information for purposes consistent with that mandate. We found the collection of driver’s licence and other identification numbers to be reasonable, and dismissed the complaint as not well founded.

2.5 Follow-up on the RCMP Exempt Databanks Audit

2.5.1 Context

The Privacy Act gives individuals a general right to request access to their personal information held by government institutions. That right, however, has specific limitations.

For example, the Act’s section 18 permits certain institutions to set up exempt databanks, which generally contain highly sensitive national security and criminal intelligence information.

Individuals have no access to their personal information stored in those databanks; indeed, they cannot even learn that their information is being held there.

The special and generally secretive nature of security and intelligence work may justify the exemption of certain files from public access. We certainly recognize the importance of assuring law enforcement and security partners, both domestic and foreign, that information shared in confidence will be protected accordingly.

However, in exchange for the privilege of keeping information totally exempt from public access, institutions are expected to ensure that exempt databanks contain only files that legitimately warrant inclusion. As the Privacy Commissioner remarked in 1990: “No exempt bank, once established, can be allowed to become an uncontrolled hiding place for personal information.”Footnote 2

This is because people whose names appear in exempt databanks could be at risk of harmful impacts. For example, a person’s name could be included in an exempt file simply because the individual was in the wrong place at the wrong time, talking to the wrong person. Some information may also wind up in the databank from an informant who is misinformed, or perhaps motivated by something other than civic responsibility.

If erroneous information is in an exempt bank, even entirely innocent people could have trouble obtaining security clearance for a job, or crossing an international border. Because the files remain secret, individuals may never learn the cause of their problems.

Thus, it is important that exempt files be subjected to ongoing review to ensure they merit continued inclusion in the exempt databank.

We completed an audit of the RCMP’s exempt databanks in February 2008. The audit found that the banks were not sufficiently well managed. As a result, they contained tens of thousands of files that should not have been there.

2.5.2 Follow-up audit

In 2010-2011, we followed up on the 2008 audit to assess whether the RCMP had acted on its commitments with respect to our recommendations.

Officials told us that, in response to our audit, they had re-examined all of the organization’s exempt bank holdings — with remarkable results.

In March 2008, there were 5,288 files in the national security exempt bank. By March 2011, all but 190 of the files had been removed.

The review of criminal intelligence files yielded a similar outcome. By the end of the past fiscal year, there were 2,898 files with exempt bank status. That’s 58,379 fewer files than were in there three years earlier.

In all, more than 95 percent of the re-examined files had been removed from the National Security Records and Criminal Intelligence Exempt Banks, according to the RCMP.

The RCMP also said they have addressed all our other audit recommendations. In particular:

- a new integrated accountability structure is in place to manage exempt banks, with authority delegated to specific individuals for approving the inclusion of files;

- a centralized review mechanism has been established to ensure the status of the files is accurately reflected in both automated and hard copy format;

- a mandatory two-year internal review cycle has been established for exempt banks.

The new measures to address the audit findings should provide a framework for ensuring the RCMP’s exempt bank holdings comply with the requirements of the Privacy Act and associated internal exempt bank policy.

2.6 Integrating Privacy into Public Safety Initiatives

A new generation of mobile devices, remote sensors, high-resolution cameras and analytic software has revolutionized surveillance practices and greatly facilitated the global collection, processing and sharing of data.

Police and government investigators can employ those capabilities for the benefit of a safer society. But, at the same time, the unchecked accumulation of data about the movements, activities and communications of citizens can also carry negative consequences by constraining people’s fundamental right to go about their business in anonymity and freedom from state monitoring.