Annual Report to Parliament 2009 on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

112 Kent Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 1H3

(613) 947-1698, 1-800-282-1376

Fax (613) 947-6850

TDD (613) 992-9190

© Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2010

Cat. No. IP51-1/2009

ISBN 978-1-100-51132-0

This publication is also available on our website at www.priv.gc.ca.

June 2010

The Honourable Noël A. Kinsella, Senator

The Speaker

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2009.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

June 2010

The Honourable Peter Milliken, M.P.

The Speaker

The House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6

Dear Mr. Speaker:

I have the honour to submit to Parliament the Annual Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act for the period from January 1 to December 31, 2009.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Message from the Commissioner

My fascination with privacy dates back to April 2000, when I happened to read a New York Times Magazine article about the erosion of privacy in the digital age.

The article, by the noted American legal scholar Jeffrey Rosen, described in frightening detail how access to personal information had become almost limitless thanks to computer-based technologies.

What struck me was the impossibility of deleting information and the illusions of privacy and security that we continue to indulge in – despite facts to the contrary.

Just a week after reading that article, I was asked to head up the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec, where I was responsible for enforcing provincial privacy legislation. I jumped at the opportunity to work in such a challenging, engaging and important field.

A decade later, the threats to privacy have only multiplied. Jeffrey Rosen’s closing call to action in the article that opened my eyes to the challenges of the digital world has become even more critical:

We are trained … to think of all concealment as a form of hypocrisy. But perhaps we are about to learn how much may be lost in a culture of transparency – the capacity for creativity and eccentricity, for the development of self and soul, for understanding, friendship and even love. There is nothing inevitable about the erosion of privacy in cyberspace, just as there is nothing inevitable about its reconstruction. We have the ability to rebuild some of the private spaces we have lost. What we need now is the will.Footnote 1

When I reflect back on how the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has worked to protect Canadians’ private spaces over the past seven years, I am extremely proud of our accomplishments.

While the encroachments on our privacy in the digital era are immense, we have not allowed them to bowl us over. We are willing to take a strong stand when necessary, but I believe we have also developed a reputation for taking a reasonable, flexible approach to privacy.

In many ways, 2009 was a watershed year for the Office.

We saw an exponential growth in investigations dealing with new technologies – and it seems clear that technology issues will dominate our work in the years ahead.

Our investigation into a wide-ranging complaint against Facebook made waves around the world. And that was just the most high-profile example of our 2009 work to address the privacy risks stemming from new technologies, the Internet and our increasingly online world.

New Technologies

I am struck by how quickly technologies are transforming our lives – especially in the way we communicate.

It’s hard to believe that the concept of online social networking didn’t really exist when I became Commissioner, given that Facebook alone now has more than 400 million users – and counting.

Back in 2003, we also didn’t tweet on Twitter, share our photos and videos on Flickr and YouTube, tour neighbourhoods virtually on Google Street View, or follow one another’s movements on location tracking services such as Loopt and Foursquare.

In the space of a few short years, even the telephone, it would seem, has become old-fashioned. A colleague recently described the horrified reaction of her university-aged daughter at the suggestion that she should actually pick up the telephone and call a friend: “Mom, you do not phone people; you text them.”

It is increasingly clear that if data protection authorities want to remain relevant, the online world is where they need to be. And this is, indeed, where my Office has begun to shift more and more of its attention.

In 2009, our comprehensive investigation into Facebook’s privacy policies and practices resulted in a commitment by this global social networking giant to make numerous changes in response to our concerns. We will be monitoring those changes in 2010 to ensure compliance with the agreement.

We also worked to address privacy risks related to other types of technological applications, such as street-level imaging and deep packet inspection,,which allows network providers to peer into the digital packets that make up transmissions over a network in order to, for example, search for viruses and spam. As a result of our interventions, both Google Street View and Canpages, which offer virtual, 360-degree tours of Canadian neighbourhoods, agreed to make changes to better respect the privacy rights of Canadians.

At the end of the year, we received a new complaint about Facebook, as well as complaints about another social networking site, an online dating service and some Internet retailers – setting the stage for online privacy issues to be a key focus of our work in 2010.

The online world – and technology more generally – will undoubtedly be the drivers of most emerging privacy issues in the years to come.

We’ve already responded to this shift by adding more technology experts to our staff. This team will support our investigation and inquiries work, and also provide advice and recommendations in support of audits and privacy impact assessment reviews, and reviews of proposed legislative and policy changes.

We are beginning to look at how we can deal with online privacy issues in a more proactive way in the future.

We will also need to look at our privacy laws and administrative structures to ensure they are keeping up with technological changes.

On the whole, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act is working well and we have been able to apply the law to technologies and business models that didn’t even exist when PIPEDA came into force. But it’s important to ensure that it continues to meet the challenge of emerging trends.

Cross-border Data Flows

Canada cannot function in isolation. The international picture is increasingly critical to protecting privacy here in Canada.

In today’s wired world, my national mandate to protect the personal information of Canadians demands a global approach. Protecting privacy can no longer be done on a country-by-country basis – the international data flows are too great; the technologies are evolving too rapidly; and the jurisdictional challenges are too daunting.

Internet privacy challenges are international and therefore require global thinking and global solutions.

Transborder data flows have been an area of focus from the very beginning of my mandate. I have long been concerned about the risks to Canadians when personal information flows to countries with little or nothing in the way of legislated privacy protections. As well, privacy issues that cross borders can raise jurisdictional questions and be far more complex to investigate.

In order to address the growing challenges, we have been a keen participant in several initiatives aimed at developing global privacy solutions.

In 2009, I had the honour of being invited to lead a volunteer group that is helping the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development plan a series of events marking the 30th anniversary of the OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Data Flows. PIPEDA is more closely based on the OECD guidelines than any other legislation in the world.

The need for international privacy standards has been a cause close to my heart from the earliest days of my mandate. I remain convinced that we will never be able to effectively protect the personal information of Canadians unless we develop a global privacy solution.

Building a Regional Presence

It has also been a priority for me to build stronger connections with Canadians wherever they happen to live and work. I want to ensure that the Privacy Commissioner’s Office is not perceived as either too Ottawa-centric or unaware of issues outside the National Capital Region.

Perhaps partly because I am a former provincial commissioner myself, I have always seen a need to build stronger ties with provincial colleagues and other stakeholders across the country.

A couple of years ago, Parliament agreed that we needed a stronger regional presence, and funded our Office accordingly. As a result, we have a number of initiatives underway.

In Saskatchewan, for example, we are working with the province’s Information and Privacy Commissioner on a number of projects, including the development of privacy tools for Saskatchewan credit unions and small businesses.

We have also engaged a new Senior Research and Outreach Advisor to act as the face of our Office in Atlantic Canada. His outreach work is aimed at empowering individuals and business organizations in the region to protect and promote privacy.

We have recently begun looking at how to develop a more effective presence in the Toronto region, where much of Canada's business takes place. Two-thirds of our complaints against private-sector organizations involve companies headquartered in Ontario.

In recent years, we have also increased our collaboration with the provincial counterparts – particularly those with their own private sector privacy legislation. For example, we’ve conducted joint investigations and developed numerous joint guidance documents for businesses.

Strengthening the OPC

I am happy to say that one of the biggest challenges I faced when I first joined the Office in 2003 is now well behind us. My appointment came as the Office was emerging from extremely challenging times.

A big part of my job in the first few years was getting our house in order after a tumultuous period of administrative, financial and organizational crises. We implemented a strong new management and financial framework.

The fourth and fifth years were about consolidation – our rebuilt Office emerged as an effective organization.

Our focus then shifted back to where it should be: fulfilling our mandate to protect the privacy rights of all Canadians. We’re conducting ground-breaking investigations and reaching out in innovative ways to individuals and organizations.

Parliamentarians increasingly turn to us for advice; we receive speaking requests from every corner of the country; and we are a sought-after participant in global privacy discussions. All of this tells me that we are seen as a credible and respected voice for Canadians on privacy.

Conclusion

As Privacy Commissioner, I am secure in the knowledge that the work of my Office matters – that it makes a real and positive impact on the lives of Canadians.

While we keep hearing in certain circles that privacy is dead in this age of digital exhibitionism, I strongly disagree – as do many Canadians who contact my Office.

Privacy changes shape and it changes context. It looks different to each generation. This is nothing new.

My generation recorded its secrets in diaries that we tucked under the mattress. Many of today’s youth pour their hearts out over the Internet – potentially for all the world to see.

Although notions about privacy do shift, the concept of privacy continues to be critical – even for those who share so much online. Some version of privacy will always play a central role in democratic societies, where individuals are respected and their personal dignity is protected.

I confess that increasingly complex threats to privacy sometimes keep me up at night and that I struggle to understand the desire of some to make so much of their private lives so public.

That said, I am fundamentally optimistic about the future of privacy. This is because I take comfort in the fact that people do care about privacy.

One of the great privileges of being Privacy Commissioner is having the opportunity to meet Canadians from across the country. And, over the years, I have been struck by the fact that so many people – old and young – speak with deep passion about the need for privacy. When we went public with the results of our Facebook investigation, for example, it was incredibly gratifying to receive so many congratulatory e-mails and phone calls. I don’t think this Office has ever seen such a strong public reaction. It was very moving.

Privacy remains an important and cherished value for Canadians – and indeed millions of people around the globe.

As Privacy Commissioner of Canada, I have had the honour and the tremendous pleasure of working with many talented individuals – inside my own Office and beyond – who are dedicated to ensuring that privacy rights are protected.

The relatively small team at the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has been able to achieve some remarkable accomplishments thanks to their devotion to their jobs and passion for the issues – not to mention plenty of grit and determination! They have continually impressed me since the first day I arrived in the office.

I would be remiss if I did not single out Assistant Commissioner Elizabeth Denham for her strong leadership on private-sector issues. She has expertly guided the Office’s work in the new realm of enforcing PIPEDA in an online context. Assistant Commissioner Denham has raised awareness about PIPEDA obligations and championed the cause of data breach notification by strengthening our relationships with the business community, where she has developed a reputation of being fair and forthright. She fully understands the need to reach out across this wide country and work closely with provincial Commissioners. She has been a highly effective champion of our work to increase our regional presence across Canada. Her many successes are a result of her practical approach to every issue.

Privacy continues to be a value worth fighting for. I am deeply grateful to the many people who agree with me and are working in their own ways to ensure that privacy and the protection of personal information remain a defining Canadian value.

Executive Summary

Introduction

The dominant theme of our work in 2009 was the protection of privacy in an increasingly online, borderless world.

A case in point was the investigation that resulted in more public attention than any other in our Office’s history: Facebook.

The investigation was a huge undertaking for us because it was wide-ranging and the issues were incredibly complex and, in some aspects, highly technical. We were also dealing with a multinational organization based in the United States.

We expect that, as people continue to spend more time online, we will see a growing number of complaints about online organizations. And, with the digital world erasing the borders between countries, more complaints will be about organizations outside Canada.

Data without Borders

We live in a world in which global data flows have become multipoint and multidirectional.

These streams of personal information circling the globe are only going to increase as more individuals take advantage of information and communication technologies.

There are currently some 1.5 billion Internet users. A billion more people are expected to join the online world in the next 10 years, with many of the new users coming from countries such as China, India and Brazil.

The need for a global privacy standard is clear, given global data flows and ubiquitous communication and information technologies. In our interconnected world, we need to take a co-operative approach to protecting personal information.

In 2009, our Office worked with several organizations and initiatives to develop a global privacy solution, including the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, International Conference of Data Protection Commissioners and the International Organization for Standardization.

Responding to Canadians

One of the most important ways we serve Canadians is through our inquiries service and investigations branch.

In 2009, we handled 5,095 new inquiries about issues that fall under PIPEDA. These calls and letters dealt with everything from how to ask an organization for access to personal information to whether a particular company has the right to collect a digital fingerprint.

We find that more people are turning to our website when they are seeking information about privacy issues. In 2009, we developed many materials and tools for our website, including complaint and data breach reporting forms and numerous fact sheets and guidance documents for business.

Our Office received 231 new PIPEDA-related complaints for investigation in 2009 – a drop from the 422 we received the previous year.

Part of this decrease is explained by the fact that we are encouraging people to try to resolve issues directly with organizations before they make an official complaint. We’re finding that many problems can be dealt with quickly – and in a way that is satisfactory to would-be complainants.

Our investigations dealt with a wide range of issues, including the online collection and use of personal information; covert surveillance by private investigation firms; workplace surveillance, such as the use of video cameras and location-tracking devices, and the collection of driver’s licence information by retailers.

We closed 587 complaints in 2009, a significant increase compared with 412 the previous year. Our concerted effort to eliminate a backlog of complaints was successful, and this will allow us to complete future investigations far more quickly.

We were pleased that many private-sector organizations voluntarily reported data breaches to our Office. We received 58 breach reports in 2009. That was fewer than the previous year, when a large number of mortgage brokers reported breaches to us.

Protecting Privacy in a Changing Environment

We continued to stress the need to ensure that laws keep up with changing threats to privacy.

We welcomed the adoption of legislation to combat identity theft through amendments to the Criminal Code.

Important legislation aimed at fighting electronic spam, the Electronic Commerce Protection Act, was also introduced and we hope it will be passed into law in the near future. Canada is currently the only G-8 country without anti-spam legislation.

That bill also included legislative amendments that would increase our Office’s ability to share information about spam and other privacy issues with provincial and foreign counterparts who enforce laws similar to PIPEDA. It would also provide the Commissioner with greater discretion to accept complaints or discontinue investigations.

New technologies sometimes put privacy laws to the test – and this was the case in 2009 as well. Social networking sites and online street-level imaging applications, for example, highlighted new ways of collecting and using personal information.

We found that PIPEDA – a technology-neutral and principles-based law – appears to be flexible enough to guide commercial uses of new technology.

While we addressed privacy concerns in social networking as part of our investigative work, we dealt proactively with our concerns about street-level imaging during a series of discussions with Google Street View and Canpages. These discussions resulted in improved privacy protection on both websites.

We also did extensive work on the issue of deep packet inspection – both as part of an in-depth investigation and submissions to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). As well, we created a website showcasing a series of essays on deep packet inspection by leading academics and professionals working in telecommunications, law, privacy, civil liberties and computer science. The project grew out of our desire to better understand a technology that can be a tool for network traffic management, behavioural advertising, and law enforcement. We hope it will promote discussion about the privacy implications of deep packet inspection.

Privacy by the Numbers

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada in 2009

| PIPEDA inquiries received | 5,095 |

|---|---|

| PIPEDA complaints received | 231 |

| PIPEDA investigations closed | 587 |

| Draft bills and legislation reviewed for privacy implications | 12 |

| Private-sector policies or initiatives reviewed | 15 |

| Policy guidance documents issued | 19 |

| Research papers issued | 7 |

| Parliamentary committee appearances made | 18 |

| Other interactions held with Parliamentarians or staff | 69 |

| Speeches and presentations delivered | 148 |

| Formal visits from external stakeholders | 32 |

| Contribution agreements signed | 12 |

| Research contracts signed | 7 |

| Hits to Office website Hits to Office blog Total |

1,695,564 488,829 2,184,393 |

| Publications distributed | 13,689 |

| Media interviews provided | 327 |

| News releases and fact sheets issued | 24 |

Note: Unless otherwise specified, these statistics also include activities under the Privacy Act, which are described in a separate annual report.

Key Issue: Data without Borders

The increasingly global nature of information flows is raising complex challenges for privacy. Our Office has been a strong advocate for a global approach to protecting privacy when personal information crosses borders.

We live in a world where countless bits of information about us – address, birth date, credit card numbers, financial information, buying habits and more – are constantly streaming around the globe.

Dramatic advances in communications and information technologies are making transborder data flows the rule rather than the exception.

A real-life example described in a 2009 report on global data privacy illustrates how extensive and complex data flows can be:

A marketer in Spain uses criteria developed by an analytics vendor in India to select a list of customers from a global customer relationship management system in the United States. This customer list is transferred to a telemarketing call centre in Mexico, which contacts the Spanish consumers. Those telemarketing campaign results are ultimately fed back to the United States in order to update the customer management system.Footnote 2

This single marketing campaign involved sending personal data back and forth between four countries and three continents. Personal information from this single transaction is subject to the jurisdiction – and the vastly different privacy regimes – of each of those countries.

Many of our own routine, daily activities involve our personal information leaving the country.

When we send e-mail, search the Internet or buy things online, our personal information may find its way into databases located in countries with less robust privacy protection regimes.

And when we provide information about ourselves over the telephone in order to book a home service call or for computer help it’s increasingly likely that we’re speaking to someone on the other side of the globe.

These shifts are changing the nature of our work. For example, we have received complaints from Canadians about online companies that have no, or little, physical presence in Canada. The Facebook investigation has been the most prominent, but not the only example to date.

Our message to business has been consistent: If you offer online products and services in Canada, you must ensure that you are in compliance with Canadian privacy laws.

The fact that we are seeing a growing number of complaints involving more than one jurisdiction has prompted us to explore ways in which to increase our collaboration with data protection regulators at the provincial level as well as in other countries.

It has been said that “the blood running through the veins of twenty-first century commerce will increasingly consist of information about individuals.” Footnote 3 Those veins clearly stretch around our planet.

At the same time, more and more personal data is being shared between the private sector and governments trying to combat terrorism and transnational crimes such as fraud and money laundering.

When personal information moves across borders, people may lose some of their privacy rights such as the ability to request access to their information to ensure its security or to seek redress by a data protection authority.

International Efforts

Increasingly, the only way to protect Canadians’ privacy is by working with other countries to ensure adequate levels of protection for personal information around the globe.

International affairs have been a top priority of our Office for several years. We are working on global privacy solutions with a number of international organizations.

It’s important to be involved for many reasons: Robust international standards are critical for the privacy rights of Canadians; we can influence outcomes by being involved; and our own data protection model – which takes a flexible, principles-based approach – is well worth promoting to other countries and international bodies.

In 2008, the Parliamentary Panel on the Funding and Oversight of Officers of Parliament recommended and Treasury Board approved giving us additional resources to support our international efforts – very important recognition of the need for a global response to the changing nature of privacy issues.

The urgent need for an international approach has also become clear to governments, data protection regulators, consumer advocates and multinational corporations around the world.

Indeed, this recognition has led to a number of initiatives – old and new – aimed at developing an international response to better protect global flows of personal information.

The search for these global solutions is not without its challenges.

It can be difficult to bring countries with different approaches together. Even on our own continent, the three largest countries have vastly different legal traditions when it comes to privacy.

Our Office has approached the international dialogue with the goal of establishing an equivalent level of basic protection around the world – one reflecting legal and cultural differences.

The following is a description of some of our involvements in international discussions on privacy protection.

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has been a key player in developing global solutions to privacy and security issues. The efforts of the OECD Working Party on Information Security and Privacy are aimed at ensuring that the global flows of information are adequately protected and fostering cooperation among enforcement authorities.

We work closely with Industry Canada, which represents the Government of Canada, to ensure that we support the important work happening at the OECD.

The OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Data Flows will be 30 years old in 2010. To mark the anniversary, the OECD is planning a series of events in 2010 to commemorate the Guidelines and to begin a discussion about whether they need to be revised.

Commissioner Stoddart has been asked to head a volunteer group helping the OECD plan these events. Our Office will help draft a discussion paper that will describe the new privacy environment and identify the challenges to protecting personal information in the 21st century. We are also participating in the planning of two workshops and a conference that will be held in October 2010 in conjunction with to the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners.

The OECD Guidelines, which are directly reflected in PIPEDA, have stood the test of time and we look forward to participating in these events in 2010.

APEC

Important work is also taking place within the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in terms of implementing the APEC Privacy Framework. We think it’s critical for Canada to be at the table for APEC discussions on privacy issues. We have an interest to ensure that Canadians’ personal information is protected wherever it flows, and, increasingly, it is flowing to our Asia-Pacific neighbours.

APEC’s 21 members – which account for over 40 percent of the global population and half of the world’s trade and total economic output – are at very different stages in terms of the development of their economic, social and legal institutions. Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong have roughly comparable privacy regimes, but the majority of APEC economies don’t have privacy legislation.

Most of the work taking place at APEC’s Data Privacy Subgroup is focused on developing “cross-border privacy rules” to govern transborder flows. Our Office has been particularly involved in developing a framework to facilitate cooperation among enforcement authorities.

The APEC process is important because it exposes member economies without privacy regimes to principles and concepts that will be helpful as they develop domestic laws.

International Organization for Standardization

The development of privacy-related standards for the use and deployment of new and existing technologies has been the subject of considerable debate and discussion within both the international standards community and the international data protection community.

The International Organization of Standardization, better known as the International Standards Organization, or ISO, signalled its intention to push ahead with this work with the creation of a working group on identity management and privacy technologies in 2006.

Our Office has been an active participant in efforts by ISO to develop and maintain standards and guidelines addressing security aspects of identity management, biometrics, and the protection of personal information.

ISO’s key projects in 2008-2009 included working towards a framework for identity management, a privacy framework, as well as identifying requirements for additional future standards and guidelines related to specific privacy-enhancing technologies.

A senior member of our Office chairs the Canadian Advisory Committee feeding into this international work and also heads the Canadian delegation to the ISO working group responsible for identity management and privacy technologies. In addition, he is the liaison officer responsible for presenting the views of the International Conference of Data Protection Commissioners to this ISO working group.

The Spanish Initiative

At the 31st International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners the world’s data protection authorities endorsed a Draft International Standard on the Protection of Privacy that was developed under the leadership of the Spanish Commissioner, Artemi Rallo Lombarte.

The draft standard was developed by an international working group with representatives from a broad range of stakeholders, including Assistant Commissioner Elizabeth Denham.

Reaching agreement on broad data protection principles was a valuable first step towards a harmonized approach to data protection. The standard demonstrates that we can agree on high-level principles.

The Accountability Project

The Accountability Project is considering what it means for an organization to be accountable for the personal information it collects and how it can demonstrate its accountability to data protection authorities and individuals.

The concept of accountability is central to PIPEDA. Assistant Commissioner Elizabeth Denham participated in the discussions that have taken place as part of the Accountability Project, which have helped us think more clearly about what the concept involves.

The discussions have also been useful because they have brought together global businesses and data protection authorities from around the world – two groups which haven’t talked enough in the past. It has provided the opportunity for some big-picture, forward-looking thinking.

At the 2009 data protection commissioners’ conference, the American-based Center for Information Policy Leadership and the Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL), the French data protection authority, announced Part II of this project, to be completed in 2010. This is important work globally and we will be participating in the second phase.

Francophonie

Our Office continues to be involved in the activities of the Association francophone des autorités de protection des données personnelles, the organization representing francophone data protection authorities from around the world.

In late 2009, Assistant Commissioner Chantal Bernier attended the francophonie association’s third international conference in Madrid, Spain, where she made a presentation on personal data protection in a globalized world.

In November 2009 we published a report providing an overview of the Canadian approach to privacy protection. We collaborated on the report with the privacy commissioners of Canada’s two francophone provinces – Quebec’s Commission d’accès à l’information and New Brunswick’s Office of the Ombudsman. The report was distributed widely among members of the francophonie association.

Memorandum of Montevideo

Youth privacy is a priority for our Office. In July, we took part in the Montevideo Group’s work on youth online privacy in the Americas.

The group brought together experts from various Latin American countries who adopted the Memorandum of Montevideo, which presents guidelines for legislators, government departments and agencies, businesses and educational institutions in Latin America to help them develop policies, practices and programs aimed at protecting youth privacy on the Internet.

In December 2009, we took part in the official launch of the Memorandum of Montevideo in Mexico.

Over the past few years, we have developed close ties with individuals working in the field of personal information protection in Latin America. We are committed to increasing this cooperation to promote youth privacy rights.

Other International Initiatives

We are seeing a number of other initiatives which could eventually have an impact on international privacy.

For example, the Security Prosperity Partnership – involving Canada, the U.S. and Mexico – has a committee looking at how protecting personal information when it crosses North American borders can facilitate trade and economic growth.

Meanwhile, the European Commission has launched a review of the European data protection framework which could result in significant changes to the European model that would bring us one step closer to a harmonized global approach.

In 2009, our Office accepted invitations to attend meetings of the Article 29 working group that advises the European Commission on data privacy and security. In one case, our European counterparts were interested in hearing from our Office and our counterparts in Quebec about how federal and provincial laws applied to the work of the World Anti-Doping Agency, which is headquartered in Montreal. We were also invited to attend hearings organized by our European colleagues on privacy issues related to search engines. Participating in the meetings offered us the opportunity to better understand what’s going on in Europe and to share information about how Canada is addressing the cross-border data flow challenge.

Change also appears to be underway in the United States. The new Director of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Protection Bureau has said it is time for the body to “reconceptualize its privacy mission and to look for a new framework to approach privacy issues.” David Vladeck, appointed in 2009, has advocated a view that data protection involves human dignity and privacy issues – and is more than simply a consumer harm problem.

We will be watching developments in the United States with great interest given the potential impact on the privacy of Canadians.

Collaborative Enforcement

Another important way in which data protection regulators are responding to expanding cross-border flows of information is by working together – both within Canada and outside.

Our Office has built strong working relationships with provinces that have their own private-sector privacy legislation. We have conducted joint investigations and have signed a memorandum of understanding on co-operation and collaboration in private-sector privacy policy, enforcement and public education with the offices of the information and privacy commissioners in Alberta and British Columbia.

We regularly collaborate with our provincial counterparts to ensure that, as much as possible, we take a consistent approach to addressing issues.

This is why we have worked with provincial counterparts to develop joint guidance for businesses on issues such as the collection of driver’s licence information.

We have also launched some joint public education initiatives aimed at both individuals and organizations. In Saskatchewan, for example, we are working in partnership with our provincial counterpart to develop privacy tools for credit unions and small businesses, with a view to using the lessons learned in other provinces and territories. As part of this work, we, in partnership with the Saskatchewan Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner, are developing a co-branded website to deliver content and interact with Saskatchewan credit unions and small- and medium-sized businesses.

We’ve seen here in Canada that we can accomplish more by working in partnership. We’d like to bring this experience to the international level in the future.

International Cooperation

At present, our ability to work collaboratively with our international counterparts on enforcement matters is limited by provisions in PIPEDA that restrict our ability to share information. However, this may change in the near future.

The Electronic Commerce Protection Act, introduced in the House of Commons in April 2009, included much-needed anti-spam provisions, (see page 73 for details) but would also increase our Office’s ability to share information with provincial and foreign counterparts who enforce laws similar to PIPEDA, allowing us to more effectively pursue investigations. Following the prorogation of Parliament at the end of 2009, this bill may be reintroduced and passed in the next session and we would welcome this step.

While we hope to be able to collaborate on investigative work in the future, we have already begun to cooperate with international organizations in other ways.

In 2009, for example, we saw the conclusion of court action taken by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), proceedings in which we intervened at the appellate level, filing a submission in support of the FTC's position. The case involved an American online data broker, Abika.com, which was operating in Canada in violation of our laws. Our Office was granted leave to file an amicus curiae brief (a written submission to help guide a court in its decision-making process) in a proceeding before the United States Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. We were also able to bring our investigation of Abika.com to a conclusion based on information provided to us by the U.S. FTC. (See pages 44 and 87 for more details.)

Future Global Directions

Many seeds are being planted, both in terms of work on international standards and closer cooperation, and it will be interesting to see how the current efforts will develop over the long term.

At this point, what we know is that there is tremendous value in the increased dialogue between various groups – data protection authorities, academics, business and advocates.

A single, global standard may be the ideal, although achieving it will be difficult. In the meantime, we should remain open to a combination of approaches that reflect differing social and cultural values.

The key will be to recognize the common elements in our different approaches and then connect the dots between them to better protect privacy on a global basis.

Key Issue: Risks Remain in Wake of Mortgage Broker Breaches

An audit of selected mortgage brokers identified numerous outstanding risks to personal information following breaches which involved alleged criminal wrongdoing.

Red flags about privacy issues with a number of mortgage brokers went up in our Office when a string of Ontario brokers notified us of breaches involving the personal information of hundreds of people.

In each of the 14 breaches reported to us in the space of a few months in mid-2008, someone impersonating an experienced mortgage agent downloaded credit reports for people who hadn’t even applied for a mortgage.

Credit reports, which contain extensive personal information, are attractive to criminals because they can be used to commit identity fraud. For example, they may include a date of birth, social insurance number and details of credit transactions and payments.

The alleged thefts by a small number of individual “rogue” agents became the subject of investigations by law enforcement agencies. (In light of these ongoing investigations, we are unable to provide detailed information related to the alleged criminal activity.)

Due to the serious and systemic nature of the incidents, the Privacy Commissioner determined there were reasonable grounds to warrant an audit of the personal information handling practices of selected mortgage brokers under Section 18 of PIPEDA.

We audited five Ontario-based brokers that had reported multiple breaches. The audit was aimed at assessing whether the selected brokers have developed and implemented policies and procedures which are sufficient to protect personal information.

While the mortgage brokers had taken some positive steps, our audit highlighted many serious outstanding issues that left the personal information of clients – not to mention any number of other people with no connection to the brokerages – at risk.

We concluded that the companies had failed to implement technological controls to raise the alarm about any future suspicious activity. We also had concerns about – among other things – security; haphazard storage of documents containing personal information; inadequate consent by clients; and a general lack of understanding about, and accountability for, privacy issues.

Background

Brokers and their agents offer products, rates and terms for individuals seeking mortgages, and act as intermediaries between individuals and lenders, including banks and credit unions.

Mortgage brokers represent a large and growing segment of the mortgage industry in Canada. A 2009 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation survey showed that mortgage brokers accounted for one-quarter of all mortgage transactions, and 44 percent of first-time home buyers used mortgage brokers to secure funding for their homes.

Brokers and agents make extensive use of personal information to provide mortgage products for their clients. During the mortgage application process, they collect personal information such as name, address, telephone numbers, dates of birth, social insurance numbers, marital status, dependants, employment information, income, assets and liabilities.

Some of this information is used to obtain credit information about the person seeking a mortgage. Brokers and agents purchase credit reports from credit reporting agencies in order to assess the individual’s eligibility for a mortgage.

Both the application and credit report information is shared with lenders and can be shared with mortgage insurers.

Our audit closely examined the policies, systems, administrative controls and safeguards implemented by five mortgage broker franchises located in Ontario, as well as four national brokers’ head offices in Toronto and Vancouver. (One of the audited mortgage brokers was independent and therefore did not have a head office.)

As part of our work, we met with officials from the Canadian Association of Accredited Mortgage Professionals, the Independent Mortgage Brokers Association of Ontario and the Financial Services Commission of Ontario. As well, we had discussions with law enforcement officials.

What Our Audit Found

During our audit, we concluded that the breaches were the result of a failure by mortgage brokers to fulfill their obligations under Canadian privacy law. PIPEDA requires that organizations safeguard the information they collect and protect it from unauthorized access. However, the brokerages did not have adequate controls to restrict – or to other monitor access to credit reports and lacked rigorous hiring processes – leaving the door open for unauthorized access to personal information.

Since the breaches occurred, the audited mortgage brokers have significantly tightened their hiring practices. However, they still did not have proper controls to limit access or monitor access to credit reports.

Our audit found significant vulnerabilities with a web-based tool that brokers use to obtain credit reports. The breaches occurred when deceptive mortgage agents improperly downloaded hundreds of credit reports that were not required for mortgages. Months after the breaches, there was still no capacity for mortgage brokers to proactively monitor for suspicious activity or to place limits on the number of credit reports that an agent can download.

We also identified concerns about a lack of comprehensive privacy policies, procedures and training. While the mortgage brokers we audited were at different levels of privacy compliance, none fully met their obligations under PIPEDA.

Key Findings and Recommendations

I. Safeguarding Personal Information

Organizations subject to PIPEDA are required to protect personal information by implementing security safeguards that are proportionate to the sensitivity of the information. We found shortcomings in several areas:

Risks to personal information had not been evaluated

None of the brokers had undertaken a threat and risk assessment to define threats, evaluate the associated risks, and recommend mitigating actions to address vulnerabilities.

Undertaking this type of assessment and acting on the recommendations could have helped these organizations meet their safeguarding obligations under PIPEDA. In the absence of a threat and risk assessment, they couldn’t show they’d identified and mitigated security risks.

Physical security at varying levels of sophistication

We found varying levels of security among the five mortgage brokers.

Some mortgage brokers did not have alarm systems to protect their places of business – not even the one who informed us that a neighbouring business had been burgled.

All but one brokerage had solid and secure walls running around their suites of offices. However, none had solid interior walls that completely enclosed individual offices, including above their dropped ceilings. This raised the risk of unauthorized access, because someone could simply remove a ceiling tile in one area, then climb over the interior wall into a neighbouring office.

Inconsistencies in document storage

Some brokers we examined used secure filing cabinets, while others stored files in unlocked cabinets or stacked files openly on the floor or on desks within accessible offices. One broker had overflow storage in an unsecured parking arcade.

In addition to paper files, all brokers we examined keep copies of electronic files containing mortgage applications, credit reports, and spreadsheets. Computer network systems holding mortgage applications and credit reports were protected with log-in requirements and virus protection software. However, none had been tested for vulnerabilities.

Inadequate controls on access to credit reports

Mortgage brokers and agents use a web-based tool in order to obtain credit reports, which are used to assess a client’s creditworthiness for mortgage products.

As discussed above, the breaches were the result of rogue agents downloading large numbers of credit reports for people who had not even applied for mortgages. This problem went unnoticed for some time.

We tested the web-based tool used to access credit reports and found that there were controls in place to authorize access to the credit reporting system. The system was encrypted and it required a log-in password.

We were deeply concerned, however, by the lack of a proactive system or measures to monitor for suspicious activity and then provide an alert. As well, due to limitations in the web-based tool, brokers were unable to limit the number of credit reports that their agents can download.

These types of controls are commonly used in other industries. For example, many organizations that provide employees with corporate credit cards use controls to monitor purchases, set spending limits and track total spending – thereby reducing the possibility of fraud.

The absence of controls meant there were only two ways for brokers to independently identify inappropriate access to the credit reporting system. The first was to review computer log files – a cumbersome process requiring technical expertise. Alternatively, a broker could monitor agents’ activities by checking invoices from credit-reporting agencies for downloaded credit reports. In other words, a problem could only be identified after the fact.

In the breaches reported to us, the brokers discovered the suspected thefts of credit reports in a few ways. In some cases, credit reporting agencies spotted suspicious activity and contacted the brokers. As well, a few people who had requested their credit reports noticed the unauthorized credit checks and alerted the brokerages. Some brokers realized there was a problem after receiving unusually large invoices for credit report requests.

Our testing also raised concerns about the creation of duplicate files containing personal information. When a credit report is accessed electronically, a duplicate report remains in the requesting computer’s “temporary” folder. Unless the contents of this folder are deleted, the credit report will remain on the computer.

Although we did not find cases where such duplicate versions resulted in a breach, there is a potential risk if computers are shared or if credit reports are accessed on public computers (ie. at an Internet café or library). Another concern is that computers containing duplicate reports could be disposed of without the necessary precaution of overwriting the hard drive – leaving highly sensitive personal information easily accessible.

Safeguard Recommendations

Audited mortgage brokers should ensure that:

- Adequate physical measures are in place, such as alarms and lockable filing cabinets; and,

- Additional controls are put in place to safeguard credit reports and limit the number that can be downloaded.

II. Identifying purpose, collection, consent, use, retention and disclosure

Organizations subject to PIPEDA are required to comply with certain fair information principles. For example, they must:

- Clearly identify the purposes for the collection of personal information before or at the time of collection;

- Obtain consent for the collection, uses and disclosures of personal information;

- Limit the information being collected to the minimum required to meet the identified purposes;

- Use and disclose the personal information only for the purpose for which it was collected; and,

- Retain personal information only for as long as necessary.

We found problems in all of these areas when we examined the mortgage brokers’ privacy polices, consent agreements and procedures:

Privacy policies not always sufficiently detailed

Privacy policies are important documents that guide how an organization protects the personal information entrusted to its care. They also inform clients and would-be clients about what an organization will do with their personal information.

Two brokerage head offices we reviewed had very detailed privacy policies posted on their websites. By contrast, another broker we examined had a privacy policy posted on its website, but it lacked sufficient detail for individuals to understand how mortgage brokers manage their personal information. Moreover, the privacy policy link on the broker’s “terms of service” page didn’t work. The remaining two brokers had privacy policies which were not posted online or made available to clients.

Over-collection of personal information

Mortgage brokers collect a variety of personal information in order to verify a potential client’s identity, including driver’s licence numbers, birth certificate information and social insurance numbers.

Social insurance numbers are frequently used by agents and brokers to differentiate between clients with similar names. However, this number is not required to conduct a credit check, nor is there a legislative requirement for its collection as part of a mortgage application.

We found that mortgage application forms did not state that the provision of a social insurance number is optional. We believe that social insurance numbers should not be used as a general identifier and their uses should be restricted to legislated purposes only.

Consent is not always obtained before collection

In order for consent to be meaningful, PIPEDA requires that the purposes for collecting, using and disclosing personal information are clearly stated. Express consent is necessary when the information is sensitive.

In order to obtain a mortgage for their clients, mortgage brokers and agents need to disclose a client’s personal information to both credit reporting agencies and lenders.

We found that, although brokers require their clients to provide written consent for brokers to access credit reports, agents sometimes obtain consent verbally and then ask clients to provide written consent after the credit report has been accessed. We also found cases where credit reports were obtained prior to consent having been recorded, and others where there was no record of consent ever having been obtained.

Clients cannot opt out of secondary uses of personal information

The consent forms we looked at stated that personal information could also be used for marketing and other secondary uses – and did not allow clients the choice of opting out of secondary uses of their personal information.

Three mortgage brokers informed us that personal information such as a names and telephone numbers may be shared with real estate agents, financial planners and other service providers as sales leads. The consent forms also permitted the use of personal information for marketing purposes such as sending newsletters and birthday greetings to clients.

Unapproved mortgages should not be retained for longer than necessary

Legislative requirements demand that mortgage brokers retain records related to approved mortgage applications for a specific time period, but there is no such requirement for unapproved applications.

However, mortgage consent forms frequently stated that files may be kept for specific periods of time – even if a mortgage was not approved by a lender. Four brokers’ consent forms stated agents “can retain and use” personal information for seven years after an application was made. One broker claimed to have a policy of destroying unapproved mortgage application within six months, but an examination of its files showed the policy was not followed. The fifth broker’s form stated that the retention period is three years.

None of the brokers were able to demonstrate a need to retain unapproved mortgage applications for long periods of time.

Disposal practices need to be strengthened

The audit also raised concerns about the disposal of personal information.

While all the brokerages had shredders, they were – with one exception – strip-cut shredders which do not adequately destroy documents. We did not find evidence that shredders were consistently used, nor could we confirm that brokers and agents who retained files in their homes disposed of them safely.

We identified one case where a broker had reused the reverse side of old, filled-out mortgage applications in order to print out new applications. This practice could clearly result in a client’s personal information being shared with someone who has no need to know.

“Identifying” Recommendations

The mortgage brokers we audited should:

- Not routinely collect and retain personal information, such as social insurance numbers, unless necessary to fulfill a specific and specified purpose and/or in accordance with the law;

- Be able to demonstrate that clients have consented to the collection of their personal information; make clients aware of all potential uses and disclosures of their personal information; and seek express consent for secondary uses of their personal information; and,

- Develop and implement policies and procedures regarding the retention of personal information.

III. Responsibility and accountability for privacy

Organizations subject to PIPEDA are responsible for the personal information in their control. They must also clearly establish who is responsible for protecting personal information and ensuring compliance with privacy legislation.

Our audit highlighted several concerns.

Mortgage brokers lack awareness of privacy roles

PIPEDA requires that organizations collecting personal information establish clear responsibility for privacy. Many organizations which handle personal information have a chief privacy officer as the key point of contact for privacy-related matters.

While all brokers we examined had designated a chief privacy officer, there was a lack of understanding about the responsibilities of this position. Many agents were unaware of who the chief privacy officer was, or to whom they should turn with a privacy-related question.

In one case, a broker franchisee told us that his organization’s chief privacy officer was located at the brokerage’s head office when, in fact, the policy manual stated that the chief privacy officer was the broker/owner himself.

Brokers and agents are not trained on privacy responsibilities

PIPEDA requires that employees be educated about privacy practices and policies and yet no agents with the mortgage broker companies we audited had been provided with formal and ongoing training on company-specific privacy practices, or their responsibilities under the law.

Brokers reported privacy breaches

None of the audited mortgage brokers had formal breach reporting policies in place at the time of the suspected thefts. However, they did contact our Office to determine how to contain and mitigate the breaches, and also notified those affected by the breaches. During the course of our audit, one of these brokers developed a formalized breach reporting policy.

Post-breach hiring processes are more stringent

Mortgage brokers significantly tightened up their hiring processes after the breaches that were reported to our Office occurred.

As of 2008, the Mortgage Brokers, Lenders and Administrators Act 2006 requires all individuals and businesses who conduct mortgage brokering activities in Ontario to be licensed by the Financial Services Commission of Ontario. To obtain a license, brokers and agents must take a course, pass an examination and undergo a criminal background check.

Prior to the breaches, brokers relied heavily on interviews, the applicant’s knowledge of the business and references. They may not necessarily have contacted lenders with whom the applicant had dealings. One broker did not always confirm the applicant’s licensing status with the Financial Services Commission of Ontario.

After the breaches, one brokerage now ensures that a regional manager from the broker’s headquarters meets all prospective employees and that a senior manager from headquarters approves all new hires. This same brokerage required that all agents be members in good standing of the Canadian Association of Accredited Mortgage Professionals. Two brokers we audited began verifying all references.

Many brokers are taking the further precaution of restricting new agents’ access to credit reporting software. For example, one broker would not permit a new agent to access credit reporting software for a minimum of 90 days.

Accountability Recommendations

The mortgage brokers we audited should:

- Clearly establish who is responsible for privacy training and monitoring compliance with PIPEDA;

- Develop and implement privacy policies and procedures to ensure compliance with PIPEDA principles, including developing information to explain the organization’s information handling policies and procedures;

- Ensure their staff are trained on company-specific privacy policies and procedures, as well as on their responsibilities under PIPEDA; and,

- Ensure that mortgage brokers and clients are aware of and can readily access privacy policies.

Response of the Audited Brokers

We sent a preliminary draft of our audit to four of the five brokers we audited; the fifth is no longer in the mortgage broker business.

All four stated that they would implement all of our recommendations.

Conclusion

Our Office appreciates the cooperation we received from the mortgage brokers we audited. For the most part, they were supportive of our work, and were open and responsive to our recommendations.

The mortgage brokers stressed to us that their key concern is service to their clients, and growing their business. Many of the privacy issues we raised – particularly around privacy procedures and practices – simply had not occurred to them.

To address this lack of understanding, our Office is now working with mortgage broker associations to develop guidance documents that will help brokers meet their privacy obligations, and also inform Canadians about how they can ensure their personal information is used appropriately by mortgage brokers.

Responding to Canadians: Complaint Investigations and Inquiries

Social networking, new technologies and surveillance concerns were some of the major themes of our investigative work in 2009.

For our Office, the most important investigations we undertake are the ones that ultimately result in change that has a meaningful impact on the day-to-day lives and privacy rights of Canadians.

As people spend more and more time online, it is increasingly clear that the Internet must be a major focus of our attention. Indeed, a growing number of our investigations are exploring how privacy laws apply in the virtual world.

In 2009, for example, we completed a comprehensive investigation into Facebook – a social networking site that has attracted millions of Canadian users. At the end of our investigation, Facebook made a commitment to put in place changes that would offer better privacy protections for users in Canada and around the world. We will closely follow the roll-out of these promised changes in 2010.

Facebook was only one of many investigations related to rapidly developing technologies with implications for privacy. We also examined the use of various technologies as part of our investigations into issues such as covert and workplace surveillance as well as street-level imaging applications and deep packet inspection.

Inquiries

Our inquiries officers have always had the extremely important responsibility of acting as Canadians’ first point of contact with our Office. They answer questions, explain how privacy legislation may – or may not – apply in specific situations and also help Canadians to understand the mandate and role of our Office.

During 2009, we handled 5,095 new inquiries about issues that fall under PIPEDA – an average of 425 per month. That’s down 20 percent from the 6,344 inquiries we received a year earlier.

It appears that more people are turning to our website rather than calling or writing us when they are seeking information about privacy issues. We have posted a number of new resource guides and fact sheets on our website. As well, we’ve introduced a new complaint form on our website, which makes it easy to understand how to make a formal complaint or report a data breach. We received close to half a million more hits to our website in 2009 than the previous year.

The drop in inquiries numbers is also due in part to the introduction of a new case management system which tracks some statistics differently. In the past, an inquiry from one individual about two different issues was counted twice. Now, the system would count that call as one inquiry.

Amongst the calls and letters that we continue to receive, we have noticed an increase in inquiries related to how online organizations are handling personal information. Following media reports about our Facebook investigation, for example, we received numerous inquiries about social networking sites.

In some cases, we are hearing from Canadians who have typed their name into a search engine and been surprised to find their personal information on a particular website.

A long-standing concern that we still receive many calls about is the use of social insurance numbers by organizations. We also receive numerous inquiries about the collection of other types of information such as driver’s licence numbers. A question we hear often is: Can they do that?

Some people who contact us mistakenly believe that our Office can levy fines against organizations. We want to ensure their expectations are in line with what we can provide.

When people call about a problem they’ve experienced with a particular organization, one of the key questions we ask is: Have you spoken with that organization about your concerns?

Problems can often be resolved quickly – and without initiating a formal complaint investigation process – when individuals deal directly with an organization. In some cases, we see that even problems which remain unresolved after discussions with front-line employees can be addressed with a phone call to the organization’s chief privacy officer. We maintain a database of chief privacy officers so that we can ensure that people with a privacy concern can easily contact the right person within an organization.

This is why we encourage people to initially deal directly with an organization when they have a concern.

However, where a problem cannot be resolved between the parties, we ask people to come back to us to further discuss whether a formal complaint should be made.

Besides answering questions over the telephone, we have a large number of fact sheets and guidance documents which can help people to understand privacy issues related to the collection and use of their personal information. For example, in 2009 we published information on: the collection of driver’s licence information in the retail sector; street-level imaging; PIPEDA and anti-money laundering legislation; the processing of personal data across borders and covert video surveillance in the private sector.

Complaints

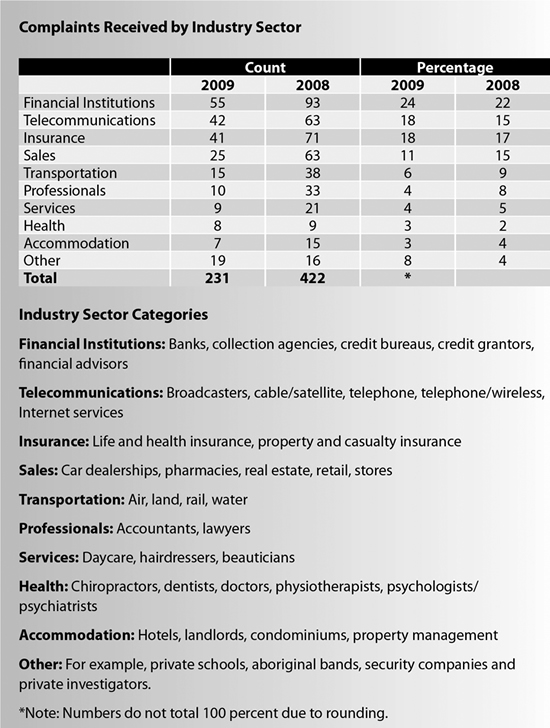

Our Office received 231 new PIPEDA-related complaints in 2009. This represents a substantial drop from 2008, when we received 422.

Meanwhile, we closed 587 complaints, compared with 412 the previous year.

We believe that a big reason for the decreased number of incoming complaints is our success in helping people to deal with concerns more efficiently. Many of the problems that people have called us about were solved informally with a phone call to the right person within an organization.

As a result, we will increasingly be able to focus our investigative resources where they belong – on more complex cases or significant or systemic privacy issues.

Our Facebook investigation, for example, involved many complicated and technical issues which warranted a comprehensive investigation. Increasingly, we are seeing complaints involving new technological applications that demand a thorough examination.

Facebook was also an example of the increasing number of investigations we undertake that involve companies based outside of Canada. This reflects the dramatic growth in transborder data flows.

Another investigation involving new technologies examined how Bell Canada uses deep packet inspection to manage traffic on its telecommunications networks. The investigation concluded the way in which network traffic was being managed was generally acceptable, but the Assistant Commissioner also emphasized that expanded use of deep packet inspection would require renewed consent.

Other issues we dealt with in our investigative work included covert surveillance by private sector organizations, workplace surveillance, including the use of video cameras and location-tracking devices, and the collection of driver’s licence information.

While the overall number of complaints we received fell, there was little change in the distribution of these complaints amongst industry sectors.

Financial institutions, the telecommunications sector and insurance companies were once again the targets of the largest numbers of complaints. Together, the three sectors were the subject of more than half of all complaints to our Office.

The size of these industries and the enormous number of transactions they conduct with individual Canadians each year is a major factor explaining their consistently high rankings when we break down complaints by sector.

One of the trends we continue to see with respect to insurance-related complaints is the use of lawyers or “facilitators” to file complaints on behalf of complainants. Most of these cases involve issues around access to personal information, collection of personal information, or consent for the disclosure of personal information. Facilitated complaints made up more than a quarter of all backlogged complaints in mid-2009.

In many cases, the complaint relates to a legal dispute between an individual and an insurer, a medical examiner or other benefit providers. These complainants often file multiple complaints related to the same issue. Gathering evidence is sometimes challenging because the complaints flow from an event which occurred several years earlier; the cases often involve a first party, second party and third party insurer and benefits schedules.

Three types of complaints – access, use and disclosure, and collection – continued to make up the lion’s share (68 percent) of all the complaints we receive.

We noticed a significant increase in the proportion of complaints dealing with access to personal information – 28 percent of total complaints, compared with 17 percent the previous year. Many small- and medium-sized businesses are still lacking in awareness of individuals’ right to access their personal information under PIPEDA and also of how to process access requests within legislated timelines.

Snapshot of 2009 Investigations

The following is a look at some of the investigations completed during 2009. Additional details about many of these cases are available on our website.

We have named the organizations that are the subject of complaints only where we have determined that it is the public interest to do so.

Investigations Involving Cross-border Data Issues

As Canadians increasingly live their lives online – making purchases from web-based retailers and communicating with friends via social networking sites and so on – it is not surprising that more and more of the privacy issues they encounter will be with organizations that have little or no “bricks and mortar” presence in Canada.

For our Office, this means we are beginning to receive more complaints about multinational – often U.S.-based – corporations.

PIPEDA applies to transactions involving personal information when there is a real and substantial connection to Canada. This includes online transactions and even, in certain circumstances, where the organization is based outside Canada.

In July 2009, Assistant Commissioner Denham released her findings in a comprehensive investigation into the privacy practices of Facebook, a California-based social networking site with millions of Canadian users. The investigation was prompted by a complaint from the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic at the University of Ottawa.

The investigation report uncovered a number of privacy problems. The most significant of these involved the risks posed by the over-sharing of personal information with third-party developers of Facebook applications such as games and quizzes.

With more than one million developers around the globe, the Assistant Commissioner was concerned about a lack of adequate safeguards to effectively restrict those developers from accessing users’ personal information, along with information about their online “friends.”

Another concern was that, in some cases, Facebook was not providing enough information to allow users to understand how their personal information would be handled. For example, there was confusing information about the distinction between account deactivation – whereby personal information is held in digital storage – and deletion – whereby personal information is actually erased from Facebook servers.

At the end of the investigation, Facebook committed to making a number of changes to improve privacy protections for its users.

Most significantly, Facebook agreed to retrofit its application platform in a way that will prevent any application from accessing information until it obtains express consent for each category of personal information it wishes to access. Under this new permissions model, users adding an application would be advised that the application wants access to specific categories of information. The user would be able to control which categories of information an application is permitted to access. There would also be a link to a statement by the developer to explain how it will use the data. This change required significant technological changes and was expected to take one year to implement.

Facebook also agreed to introduce changes to help users to better understand how their personal information will be used and, ultimately, to make more informed decisions about how widely to share that information.

As agreed, Facebook has been reporting to us on those commitments and undertakings. We will continue to monitor all developments closely, and provide our feedback.

The Facebook investigation was reported by media outlets around the world and raised our profile amongst global corporations.

Immediately after the report was published, another major social networking site contacted us regarding compliance with Canadian laws and other U.S.-based companies requested meetings to talk to us about their global applications. This is a new development that we hope will lead to better privacy protections for Canadians and people around the world.

Accusearch, Inc. (Abika.com)

Responding to a complaint, we investigated the information-handling practices of a Wyoming-based search services website. Assistant Commissioner Denham found it violated key provisions of PIPEDA in its collection, use and disclosure of the personal information of residents of Canada.

Abika.com provided a range of search services using third-party researchers who search for and obtain personal information about individuals from a variety of public and private records and databanks. It also compiled “psychological profiles” which purport to describe an individual’s behaviour and personal traits.

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) separately investigated the activities of Abika.com. (See page 87 for information about our Office’s involvement in supporting the FTC in a legal case involving Abika.com.)

Based largely on information provided by the FTC, our investigation determined that the American company collected, used and disclosed to third parties the personal information of Canadians, without their knowledge or consent, in contravention of PIPEDA. As well, in some cases, the company knowingly turned over the personal information of Canadians for purposes that a reasonable person would consider highly inappropriate in almost any circumstances.

The Assistant Commissioner recommended Abika.com stop collecting, using and disclosing the personal information of people living in Canada without their knowledge and consent. Given the effectiveness of the FTC’s efforts against this organization, in particular the successful outcome of the FTC’s legal case, it was determined that no further action was required by our Office.

The investigation marked an important step in international co-operation and collaboration that will become increasingly necessary to adequately protect privacy rights on both sides of the border in years to come.

Investigations Involving New Technologies

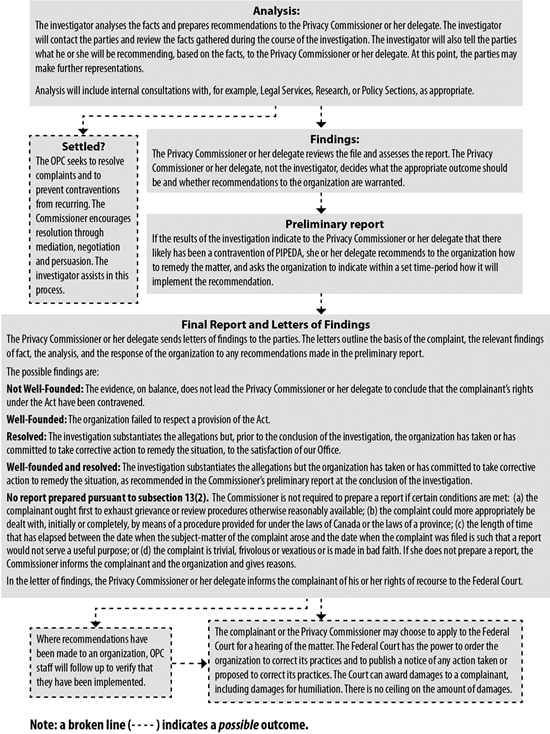

Bell Canada – Deep Packet Inspection