Bill C-13, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act

Submission to the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs

November 19, 2014

The Honourable Bob Runciman, Senator

Chair, Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs

The Senate of Canada

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1A 0A4

Dear Mr. Chair:

Thank you for the invitation from the Committee to present the views of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) in connection with Bill C-13, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act. As the debates both in Parliament and among Canadians attest, the Bill engages complex legal, technical and privacy issues. We hope this submission will assist your study of the legislation.

General background

We regard the first aim of the Bill as commendable, specifically the sections treating the serious issues of online bullying, harassment and non-consensual circulation of intimate images. Stalking through social networks, cyber-bullying and other forms of Internet exploitation are demeaning forms of abuse that affect Canadians, especially young people. Clearly, Internet bullying and online shaming can have lasting privacy repercussions for victims. Parents, teachers and police have called for reform, and rightly so.

As a consequence, we believe that the criminalization of the distribution of intimate images without consent and extending Criminal Code provisions to cover new channels of communication will send an important signal that such offensive actions will not be tolerated. Canadians surely have a legal right to be free from harassment, bullying and personal invasion in the physical world. In a digital era, government must work to ensure these rights are equally respected online.

Summary of privacy issues

In our submission, the main privacy issues that arise in the context of Bill C-13 relate to the other provisions that propose to expand the investigatory powers afforded to peace officers and public officers under the Criminal Code. Given our advisory function to Parliament, we would like to highlight four specific privacy issues stemming from these aspects of the Bill that merit close scrutiny:

- The thresholds for the use of the new powers and procedures;

- The range of departments, agencies and officials who can use these powers;

- The transparency and accountability framework governing their use; and,

- The need for legal clarity (following the Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Spencer) on warrantless requests, voluntary disclosure, and legal immunity.

Thresholds for the use of the new powers and procedures

One aim of the Bill is to amend various legal thresholds for the use of the new investigative powers and procedures. What follows is a list of the new powers, their duration and the legal threshold for their authorization:

| Investigative Power | Example of data obtained | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation demand - 21 days (s. 487.012) |

No data |

suspicion |

| Preservation order – three months (s. 487.013) |

No data |

suspicion |

| General production order (s. 487.014) |

Any stored data |

belief |

| Production order to trace specified communication (s. 487.015) |

Email, Internet Protocol (IP) and MAC addresses |

suspicion |

| Production order – transmission data (s. 487.016) |

IP addresses, website domains / pages visited, file sharing and other protocols, packet numbers, search engine search terms and email addresses |

suspicion |

| Production order – tracking data (s. 487.017) |

Location information, GPS coordinates |

suspicion |

| Production order – financial data (s. 487.018) |

Account holder information, types of accounts, date of account, current address |

suspicion |

| Warrant for tracking device – transactions and things (s. 492.1(1)) |

Locations of credit or bank card usage, movements of vehicles |

suspicion |

| Warrant for tracking device – individuals (s. 492.1(2)) |

Location of tracked individual (via personal mobile device) |

belief |

| Warrant for transmission data recorder (s. 492.2) |

See above |

suspicion |

The bulk of the new powers may be used where investigators have a mere suspicion of wrongdoing, as opposed to a higher threshold of reasonable belief that the search will provide evidence of a specific crime. The difference between these two thresholds represents a marked difference in privacy protection.

The potential level of government intrusion must be matched by commensurate judicial scrutiny and an appropriate legal standard for authorization. There should be evidence of a higher probability of wrongdoing before information about individuals’ private communications or their digital activities are compelled. Downgrading to a “reasonable suspicion” standard should be a necessary and proportionate response to a demonstrated problem, and in our view, a more compelling case for the use of a reduced legal threshold must be presented and thoroughly examined.

Courts have upheld the lower reasonable suspicion standard only in limited situations where privacy interests are reduced or where state objectives of public importance are predominant. The government defends the lower thresholds in Bill C-13 in part based on the argument that the information sought is not very sensitive and triggers a lower expectation of privacy. With respect, we think that argument does not give appropriate weight to the teachings of the Supreme Court of Canada in the recent R. v. Spencer decision. In that case, the Supreme Court clearly held that the protection of privacy interests requires us to look not only at the specific information being sought – no matter how seemingly innocuous – but also at what the information may further reveal.

The powers provided under Bill C-13 will allow access to potentially sensitive personal information for all manner of investigation and enforcement action. Electronic surveillance and data analyses have become increasingly powerful in the digital era, given that every transaction, every message, every online search, every call and movement across the Internet leaves a recorded trace and is, therefore, potentially subject to scrutiny. While others have argued that the higher threshold should be reserved for the content of communications, we would stress that various forms of transaction and transmission data could be just as sensitive and revealing depending on the context.

As the Supreme Court noted in Spencer, “the Internet has exponentially increased both the quality and quantity of information that is stored about Internet users,” and that such information can “provide detailed information about users’ interests.” To underscore this point, we include a technical and legal overview of Metadata and Privacy, a report published by my office last month, which demonstrates the various forms of personal data that could be derived from metadata obtained at the lower legal threshold being proposed by the Bill. An accompanying infographic and link to the full report can be found in the Annex to this submission.

Some witnesses who have appeared before this Committee have argued that they require a lower threshold for authorization in order to access information at the early stages of an investigation. Indeed, the “reasonable suspicion” standard requires less groundwork for investigators and fewer facts to be put before court officers reviewing requests for surveillance. But would having a higher threshold, as some have suggested, impede effective investigation and prosecution of online crime, and carve out a crime-friendly Internet landscape? We do not believe so. Again, in Spencer, the Court rejected that argument noting that the police, in that case, had ample information to obtain a production order for what they needed even at the early stages of the investigation.

If the “reasonable suspicion” standard is kept, there are no legal limitations at this point to prevent the various authorities who can avail themselves of these new powers from using the evidence gathered for broad surveillance or fishing expeditions. For example, once public officials have information based on mere suspicion for purposes of investigating a specific crime, there is currently no legal limitation to prevent this open-ended category of public officers from using potentially sensitive information for a multitude of other, much less compelling circumstances. In short, the proper thresholds do not depend, as the Supreme Court has said, on whether privacy shelters legal or illegal activity, or on the legal or illegal nature of the information being sought. The issue, therefore, is not one of concealing illegal use of the Internet for cyberbullying or child pornography at all costs. Rather, it is a matter of preserving the privacy interests of all Canadians generally “with respect to computers which they use in their home for private purposes.”

Fundamentally, it is our view that reasonable suspicion is too low a threshold for allowing a wide assortment of public officers, and for a multitude of purposes, to access personal information that can be so revealing. Therefore, I recommend it be replaced by a “reasonable grounds to believe” threshold with respect to the new productions orders and warrants. Alternatively, if the “reasonable grounds to suspect” standard is maintained, the Bill should clarify that the use of evidence gathered pursuant to such a court order should be limited to investigating only the alleged crime specified in the court application and not for other purposes.

Recommendation: While “reasonable suspicion” may be acceptable for preservation of data, the traditional standard of “reasonable grounds to believe” should continue to prevail as the appropriate judicial threshold for the authorization of the new production orders and warrants being proposed. Alternatively, should the Committee support the lower standard of reasonable suspicion, we recommend limiting the use of information obtained through those powers to the investigation of the alleged crime specified in the court application and not for other purposes.

Range of departments, agencies and officials who can use new powers

A second aspect of the Bill that merits serious scrutiny is the wide range of governmental authorities and governmental bodies – well beyond police - that will be able to use the new investigative powers. A very broad range of actors - at all levels of government - will be able to avail themselves of the new investigative powers including demanding the preservation of data, seeking production of personal records or private communications, or requesting warrants to collect tracking data associated with vehicles, transactions or individuals.

The language in proposed section 487.011 of the Criminal Code defines a public officer as anyone “appointed or designated to administer or enforce a federal or provincial law and whose duties include the enforcement of this Act or any other Act of Parliament.” That means that, in addition to police officers, the Bill will empower mayors, wardens, reeves, sheriffs, certain airline pilots, customs officers, fisheries officers, and any federal or provincial officer whose duties include the enforcement of a federal or provincial law.

While police organizations and security agencies have some form of oversight and reporting requirements, other actors falling under the definition of “public officer” are not subject to dedicated review or required to report on the use of surveillance powers. Given these gaps in accountability and oversight, we would urge caution in providing such a wide range of actors with such significant search powers, especially where, in our view, a demonstrable case has not yet been made.

Recommendation: Use of the proposed search powers should be limited to traditional “peace officers” engaged in criminal investigations. Alternatively, the open-ended category of public officers should be replaced by a closed list of designated public officers who would be afforded these new powers in respect of specific legislative duties.

Transparency and accountability for the use of the powers

In our view, the lack of provisions requiring transparency or regular public reporting on the use of the new powers is a concern. On the commercial side, many Internet service and telecommunications companies have begun voluntarily reporting on a regular basis, aggregate data on the numbers and categories of instances where they have shared information with law enforcement agencies. Companies, like government institutions, also need to concern themselves with openness, transparency and public trust.

In terms of reporting to Parliament and the public on how surveillance measures are used, Canada already has a model precedent to consider with respect to federal law enforcement. Since 1977, the Annual Report on the Use of Electronic Surveillance tabled annually in Parliament (pursuant to section 195 of the Criminal Code) has provided a model for reporting on sensitive investigations. These provisions were updated and extended by new legislation as recently as March 2013 pursuant to directions set out by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Annual reporting on the new powers would mesh with the existing process to provide a measure of transparency and accountability. Reported statistics would also provide Parliamentarians and the public with insight into the usage, results and overall effectiveness of such powers. Finally, they would also support the statutory review of the provisions by a House of Commons Committee as is being proposed under section 487.021.

Recommendation: The new powers listed in sections 487.011 to 487.02 as well as warrantless requests should be subject to regular public reporting as required under section 195 of the Criminal Code for other forms of electronic surveillance

Legal clarity (post-Spencer) on government requests, voluntary disclosure, and legal immunity

A final concern of our Office relates to the Bill’s proposed new section 487.0195 of the Criminal Code. This immunity provision would protect from legal liability those persons who voluntarily disclose personal information in response to government requests without a warrant. Where the state seeks access to personal information held by organizations, including Internet service providers, R. v. Spencer clearly limited warrantless searches to situations where there are exigent circumstances, a reasonable law, or where the information does not attract a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Carrying out a “reasonable expectation of privacy” analysis is complex, highly contextual and difficult for organizations and individuals to undertake in each individual case. This will place an unfairly heavy burden on organizations especially where they might lack the time, knowledge or resources to challenge or refuse such requests. In our view, the immunity provision will exacerbate ongoing confusion with respect to organizations’ obligations under paragraph 7(3)(c.1) of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). Even after the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R. v. Spencer, companies and government are still debating the concept of “lawful authority” for the purposes of 7(3)(c.1) of PIPEDA.1Footnote 1

As a result, Canadians remain in the dark as to what may happen to their personal information. The government claims that nothing in Bill C-13 needs to be changed as a result of R. v. Spencer, leaving Canadians to wonder what impact the ruling has, if any. In response to various MP questions regarding warrantless requests made to third party organizations over the past few years, several departments and agencies provided little or no data. While some telecommunications companies have announced that they would no longer provide personal information to law enforcement absent judicial authorization, a reasonable law or exigent circumstances, other companies provided no such assurance.

We would therefore urge the Committee to put an end to this state of ambiguity and clarify what, if anything, remains of the common law policing powers to obtain information without a warrant post-Spencer. This would provide clarity to individuals, private-sector organizations and law enforcement officials as to when the state can obtain personal information via warrantless access. Bill C-13 should be amended to state explicitly that discretionary disclosures to law enforcement following a request should be permissible only under a reasonable law, with judicial authorization or in exigent circumstances.

While some may argue that this would remove an important investigative tool for law enforcement to gather information outside these situations, we see no need to maintain a tool that permits disclosure of personal information below what is already a low threshold of reasonable suspicion. Alternatively, to achieve greater certainty for Canadians about what can or cannot be done with their personal information, Parliament could prescribe limited circumstances under which personal information which does not attract a reasonable expectation of privacy could be disclosed.

Recommendation: The proposed section 487.0195 should be amended to state explicitly that personal information may only be disclosed to law enforcement in the presence of a reasonable law, judicial authorization or exigent circumstances. Alternatively, Parliament could prescribe limited circumstances under which personal information which does not attract a reasonable expectation of privacy could be disclosed.

Conclusion

In sum, it is important to remember that these new investigative tools would sweep up vast amounts of potentially sensitive personal information by an open-ended group of authorities for a wide range of purposes, without any public reporting requirements. Thank you once again for the opportunity to present the Committee with our views on the proposal. We look forward to the discussion and any questions of your Members in connection with the current study.

Sincerely,

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Encl.

c.c Shayla Anwar, Clerk

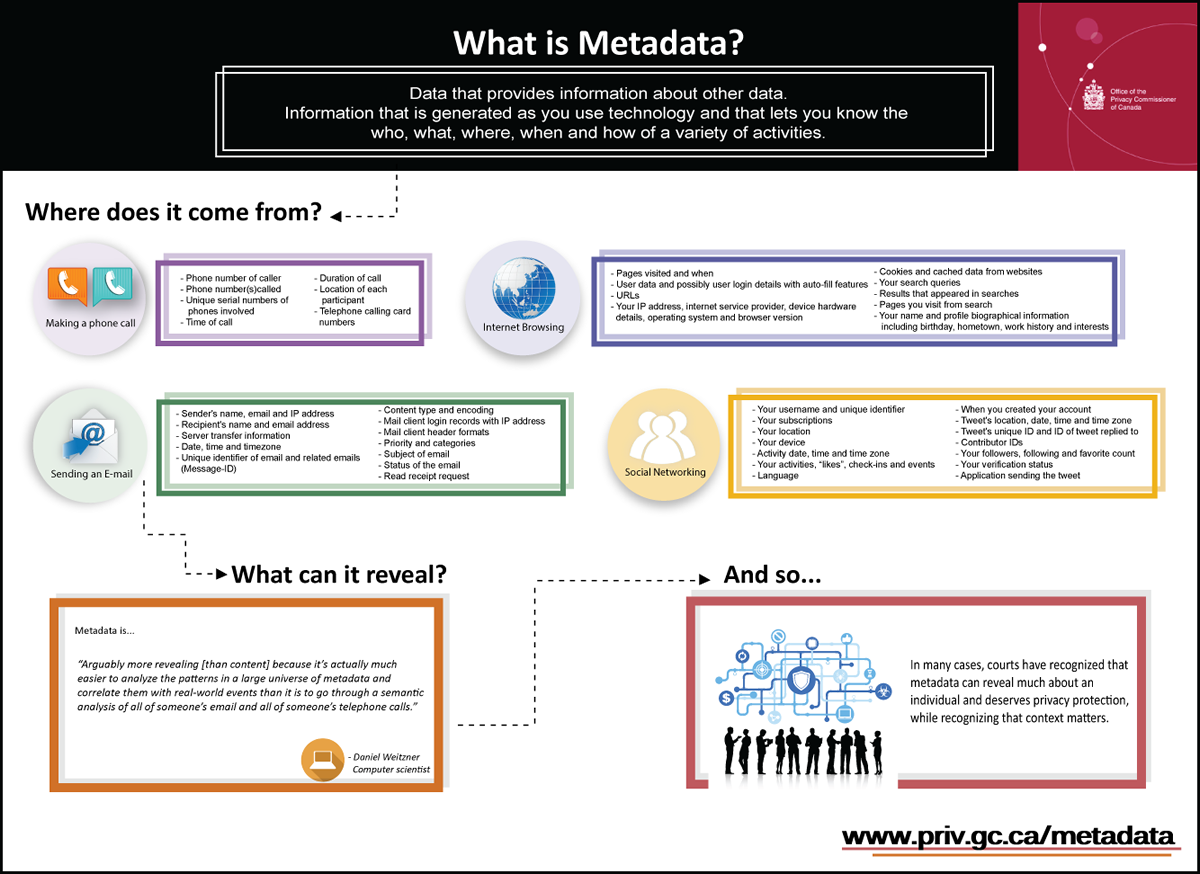

Annex – Forms and examples of metadata subject to access and surveillance through new warrant provisions in Bill C-31

Text version

What is metadata?

Data that provides information about other data.

Information that is generated as you use technology and that lets you know the who, what, where, when and how of a variety of activities.

Where does it come from?

Making a phone call

- Phone number of caller

- Phone number(s)called

- Unique serial numbers of phones involved

- Time of call

- Duration of call

- Location of each participant

- Telephone calling card numbers

Internet Browsing

- Pages visited and when

- User data and possibly user login details with auto-fill features

- URLs

- Your IP address, internet service provider, device hardware details, operating system and browser version

- Cookies and cached data from websites

- Your search queries

- Results that appeared in searches

- Pages you visit from search

- Your name and profile biographical information including birthday, hometown, work history and interests

Sending an E-mail

- Sender's name, email and IP address

- Recipient's name and email address

- Server transfer information

- Date, time and timezone

- Unique identifier of email and related emails (Message-ID)

- Content type and encoding

- Mail client login records with IP address

- Mail client header formats

- Priority and categories

- Subject of email

- Status of the email

- Read receipt request

Social Networking

- Your username and unique identifier

- Your subscriptions

- Your location

- Your device

- Activity date, time and time zone

- Your activities, "likes", check-ins and events

- Language

- When you created your account

- Tweet's location, date, time and time zone

- Tweet's unique ID and ID of tweet replied to

- Contributor IDs

- Your followers, following and favorite count

- Your verification status

- Application sending the tweet

- When you created your account

- Tweet's location, date, time and time zone

- Tweet's unique ID and ID of tweet replied to

- Contributor IDs

- Your followers, following and favorite count

- Your verification status

- Application sending the tweet

What can it reveal?

Metadata is...

“Arguably more revealing [than content] because it’s actually much easier to analyze the patterns in a large universe of metadata and correlate them with real-world events than it is to go through a semantic analysis of all of someone’s email and all of someone’s telephone calls.”

- Daniel Weitzner

Computer Scientist

And so…

In many cases, courts have recognized that metadata can reveal much about an individual and deserves privacy protection, while recognizing that context matters.

- Date modified: