Children are more connected than ever and often miles ahead of their parents when it comes to navigating the Internet and mobile applications (apps).

They’re also among our most vulnerable demographic groups and, in their quest to access their favourite game or social network, they may be apt to give out personal information without any thought to the potential privacy ramifications.

For this reason, the Global Privacy Enforcement Network made Children’s Privacy the theme of its 3rd annual Privacy Sweep.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, along with 28 other privacy enforcement authorities across the country and around the globe, assessed the privacy communications and practices of some 1,494 websites and mobile apps.

The goal: to find out which of them collect personal information, what type of personal information they collect, whether protective controls exist to limit the collection and whether a simple means to delete account information exists.

By briefly interacting with the websites and apps, the exercise was meant to recreate the consumer experience – in this case, the experience of children under the age of 12. Our sweepers, which included a number of adult volunteers as well as nine children, ultimately sought to assess privacy controls based on four key indicators:

- Collection of children’s data: Does the app/website collect children’s personal information and if so, what information is collected? (Ex. Name, email, date of birth, address, phone number, photo/video/audio.) Does a privacy policy or other privacy communications exist and if so, does it clearly explain the app/website’s personal information handling practices?

- Protective controls: Do protective controls exist and do they effectively limit the collection of personal data? (Ex. Prompts for parental involvement, warnings when leaving the site, pre-made avatars/usernames, moderated chats/message boards to prevent inadvertent sharing of personal information.) Are privacy communications tailored to children? (Ex. Simple language, large print, audio, animation.)

- Means to delete account information: Is there a simple means for deleting account information?

- Overall concerns about a child using the app/website: Overall, would I be comfortable with a child using this app/website?

In total, our Office examined 172 websites and mobile apps for both Android and iOS platforms. We focused on websites and apps that are targeted at or popular among children 12 and under.

Some 118 websites and apps appeared to be targeted directly at children, while 54 were considered popular among them. In other words, while designed for older audiences or audiences of all ages, children are said to be frequent users of these apps and websites.

The bulk of websites and apps swept were based in Canada and the United States. Our Sweep included a significant number of games and educational websites and apps, as well as leisure websites and apps hosted, for example, by museums or zoos. Traditional and social media apps and websites rounded out the list.

Before delving in, let’s be clear on a few points: Since apps and websites are constantly evolving, it’s best to think about our results as a snapshot in time. Also note that the Sweep was not a formal investigation. We did not seek to conclusively identify compliance issues or possible violations of privacy legislation. This was not an assessment of an app or website’s overall privacy practices, nor was it meant to provide an in-depth analysis of the design and development of the apps or websites examined.

Instead, we have compared and contrasted some of the web/app features and privacy practices that we found to be particularly kid-friendly, with those we felt could benefit from some “child-proofing.” We learned a lot and hope these concrete examples will help Canadians, as well as website and app developers, better understand our conclusions.

The moderated message/chat function:

Moderated message/chat functions ensure contributions are vetted before they are posted publicly. Items may be vetted for content but also for personal information as free-text portals can open the door to the inadvertent sharing of potentially sensitive details.

Family.ca, a site clearly targeted at children, indicated its message board feature was moderated. Our Sweepers put that claim to the test by attempting to post a message that included a full name, age and hometown. A day later, here’s the modified message that went public:

ren are more connected than ever and often miles ahead of their parents when it comes to navigating the Internet and mobile applications (apps).

They’re also among our most vulnerable demographic groups and, in their quest to access their favourite game or social network, they may be apt to give out personal information without any thought to the potential privacy ramifications.

For this reason, the Global Privacy Enforcement Network made Children’s Privacy the theme of its 3rd annual Privacy Sweep.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, along with 28 other privacy enforcement authorities across the country and around the globe, assessed the privacy communications and practices of some 1,494 websites and mobile apps.

The goal: to find out which of them collect personal information, what type of personal information they collect, whether protective controls exist to limit the collection and whether a simple means to delete account information exists.

By briefly interacting with the websites and apps, the exercise was meant to recreate the consumer experience – in this case, the experience of children under the age of 12. Our sweepers, which included a number of adult volunteers as well as nine children, ultimately sought to assess privacy controls based on four key indicators:

- Collection of children’s data: Does the app/website collect children’s personal information and if so, what information is collected? (Ex. Name, email, date of birth, address, phone number, photo/video/audio.) Does a privacy policy or other privacy communications exist and if so, does it clearly explain the app/website’s personal information handling practices?

- Protective controls: Do protective controls exist and do they effectively limit the collection of personal data? (Ex. Prompts for parental involvement, warnings when leaving the site, pre-made avatars/usernames, moderated chats/message boards to prevent inadvertent sharing of personal information.) Are privacy communications tailored to children? (Ex. Simple language, large print, audio, animation.)

- Means to delete account information: Is there a simple means for deleting account information?

- Overall concerns about a child using the app/website: Overall, would I be comfortable with a child using this app/website?

In total, our Office examined 172 websites and mobile apps for both Android and iOS platforms. We focused on websites and apps that are targeted at or popular among children 12 and under.

Some 118 websites and apps appeared to be targeted directly at children, while 54 were considered popular among them. In other words, while designed for older audiences or audiences of all ages, children are said to be frequent users of these apps and websites.

The bulk of websites and apps swept were based in Canada and the United States. Our Sweep included a significant number of games and educational websites and apps, as well as leisure websites and apps hosted, for example, by museums or zoos. Traditional and social media apps and websites rounded out the list.

Before delving in, let’s be clear on a few points: Since apps and websites are constantly evolving, it’s best to think about our results as a snapshot in time. Also note that the Sweep was not a formal investigation. We did not seek to conclusively identify compliance issues or possible violations of privacy legislation. This was not an assessment of an app or website’s overall privacy practices, nor was it meant to provide an in-depth analysis of the design and development of the apps or websites examined.

Instead, we have compared and contrasted some of the web/app features and privacy practices that we found to be particularly kid-friendly, with those we felt could benefit from some “child-proofing.” We learned a lot and hope these concrete examples will help Canadians, as well as website and app developers, better understand our conclusions.

The moderated message/chat function:

Moderated message/chat functions ensure contributions are vetted before they are posted publicly. Items may be vetted for content but also for personal information as free-text portals can open the door to the inadvertent sharing of potentially sensitive details.

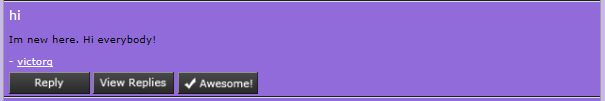

Family.ca, a site clearly targeted at children, indicated its message board feature was moderated. Our Sweepers put that claim to the test by attempting to post a message that included a full name, age and hometown. A day later, here’s the modified message that went public:

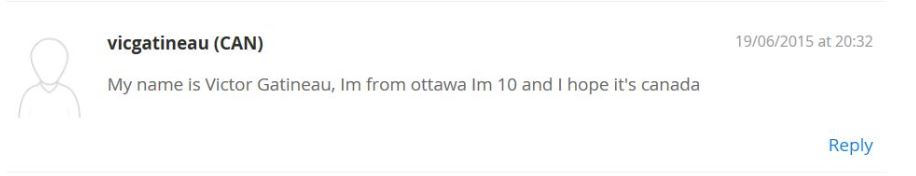

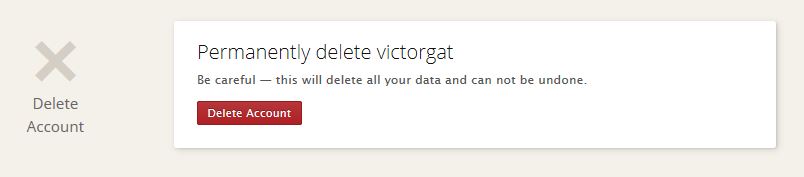

As you can see, the site even cropped the username to “victorg.” Nice catch Family.ca.

We attempted the same experiment with Lego.com. As you can see, the moderator informed us that it had rejected our post for privacy reasons. Awesome moderating decision master-builder Emmet!

As you can see, the site even cropped the username to “victorg.” Nice catch Family.ca.

We attempted the same experiment with Lego.com. As you can see, the moderator informed us that it had rejected our post for privacy reasons. Awesome moderating decision master-builder Emmet!

Kudos to Family.ca and Lego.com which have shown how a little moderation can go a long way!

By contrast, Moviestar Planet is an example of a social networking app targeted specifically at kids that displays little self-control. While the app said it is moderated for content, children were free to post selfies with titles asking, for example, others to rate them “hot or not.” Not the sort of thing you might necessarily want out there on the Internet when you grow up. We won’t display those images to protect the privacy of the children, but you can also see how our sweeper was able to include a whole lot of personal information in the free-text chat function. Big no no! What’s stopping kids from entering their address, school or where they plan to be that afternoon?

Meanwhile, sweepers noticed that websites/apps that are popular among children may moderate for certain content but not to ensure that children aren’t sharing personal details about themselves online. The website for FIFA, soccer’s governing body and a site popular with soccer fans of all ages, for instance, moderates its site to ensure that there are no violations of the Terms of Service. But as you can see below, our sweeper was able to state his age and location. Therefore this reference to moderation has more to do with the appropriateness of the content . . . You know how partisan soccer fans can get!

The website’s Terms of Service also states that it is the responsibility of parents to supervise their children’s activities on the site and that appears to be as far as FIFA’s obligation goes towards moderating the content that children may be sharing. Certainly parents have a role to play in protecting children’s privacy while online, but seriously FIFA, you are not absolved from getting in the game. If you’re already moderating for content, why not make sure kids aren’t oversharing too? This serious foul deserves a red card.

Less is more:

Leave a little mystery! Profile displays do not have to give everything away.

GamezHero.com is an example of a targeted website that allows users to display a significant amount of personal information on their user profile including name, grade, gender, age and city. While the website said it does not collect from children under 13, it had no problem posting our 10-year-old’s information. Fortunately, there was no option to load a photo!

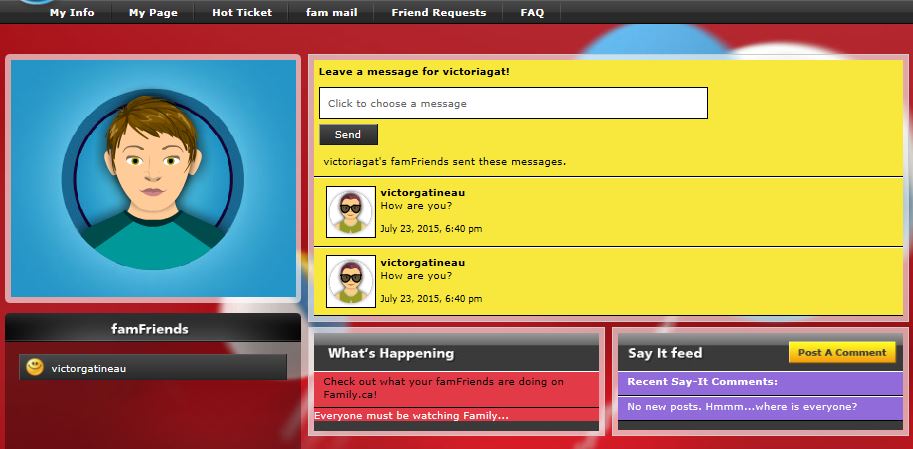

A similar interface on Family.ca, however, had limited options for sharing personal information. The photo was a preset graphic and messages were fixed text. In other words, kids could choose what to say from a list of phrases.

Things can get a little trickier with popular apps and websites. Even though many children use these sites, they are often not designed with the under 12 crowd in mind. Gurl.com is one such example. As you can see, the social platform geared at teen girls collected and posted our 10-year-old sweeper’s full name, date of birth, occupation and location.

There were also no warnings or mechanisms to prevent users from uploading photos or posting personal information on message boards, some of which broach some pretty sensitive topics such as depression, suicide and self-mutilation. Given the lack of protective controls, there’s no telling what children could post and who might see it, raising all sorts of questions about the potential for harm to one’s reputation and well-being.

For an otherwise pretty kid-friendly website, we found this next example worth mentioning. Santasvillage.ca offered kids an easy way to “get on Santa’s nice list” – by coughing up their full name and email address. In exchange, it promised to bombard subscribers with marketing materials. Not cool Santa, we’ll take the coal.

Avatars:

Selecting an image that will serve as your online identity doesn’t have to be personal. PBSkids.org is an example of a targeted website that asked our sweeper to choose from a pre-set list of icons.

Other websites/apps asked sweepers to load their own avatar which opens the door to using personal photographs. For example, the Cookie Monster Challenge app prompted us to take a selfie for our profiles. The app’s generic privacy policy also suggested personal information may be shared with third parties.

As the Cookie Monster himself might say: Parents not like when Cookie gobble up sensitive personal information like photograph and share with udder monsters.

All in a name:

Just as children should be discouraged from using a personal photo online, so too should they be discouraged from using their real name.

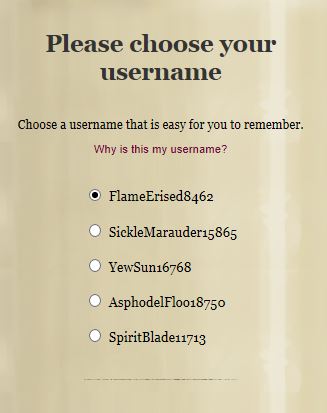

Websites such as Harry Potter fan site, Pottermore.com, don’t give kids the option. Instead, our sweepers were encouraged to select a username from a pre-set list. Thanks for thinking about the privacy of your younger Hogwarts classmates, Harry!

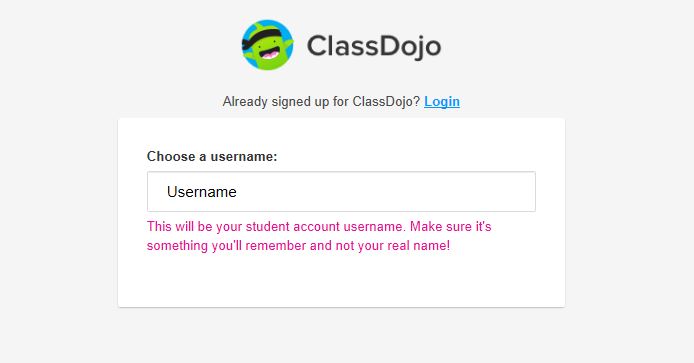

Meanwhile, Classdojo.com, a classroom management site that connects teachers, students and their parents, got a gold star for advising sweepers in simple, child-friendly language not to use their real name. But unfortunately that gold star got yanked as there was no actual mechanism to prevent us from using it.

Parental control:

On the subject of parental control, there are some effective ways to limit the functionality of a website or app to protect privacy. A great way to do that is with a parental dashboard and here are a few examples that put parents in the privacy driver’s seat.

The first was Grimm’s Red Riding Hood, an app targeted at children that allowed parents to turn certain settings on and off, such as in app purchases and access to the store.

Another example is Battle.net, a popular game website designed for children over the age of 13, even though younger children are known to frequent it. As long as young users have provided a valid parental email address, parents can control settings through a fairly comprehensive dashboard.

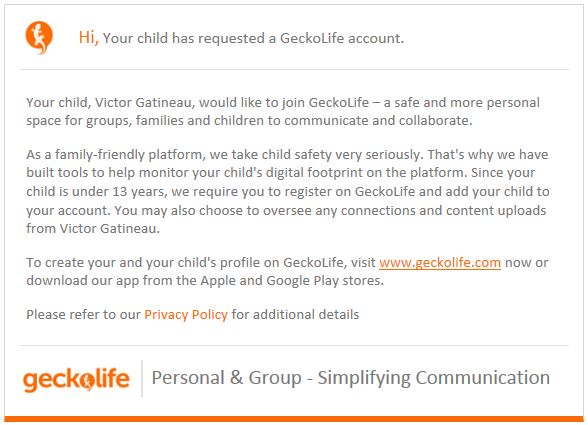

On social networking site GeckoLife.com, parents of young children must register an account, to which they can add a child.

Parents could also monitor their child’s activities, including media uploads and connections with other users, however, the website collected a fair bit of personal information in the process.

Now just as the First Year kids at Hogwarts require parental permission for weekend trips to Hogsmeade, young Pottermore.com users need parental permission to activate their account. Of course that means deploying a summoning charm: Accio parental email address. Good job on involving mum and dad!

But this website didn’t just seek mum or dad’s email address, it also asked for the child’s first name, country, date of birth and which Harry Potter books and movies you’ve read or watched before sending the parental consent link via email. Is all that information really necessary, Harry?

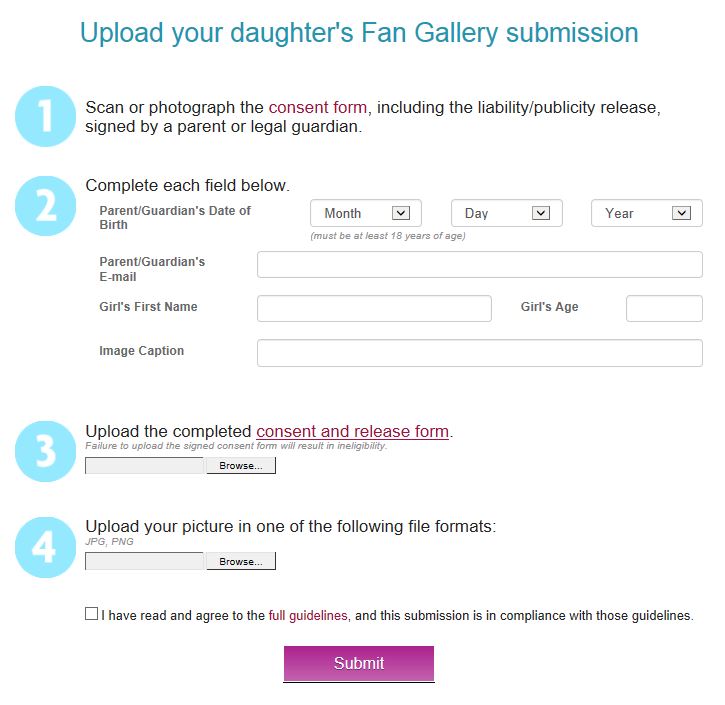

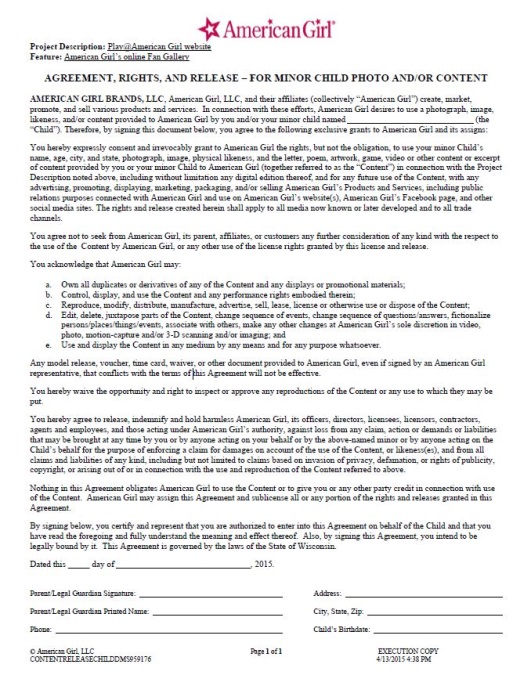

The American Girl doll website had options to collect personal information through quizzes and sweepstakes, but to post a photo of your child with their favourite doll, parents had to provide a signed waiver.

These other apps clearly targeted directly at children have found some creative ways to keep wee ones out of adult sections of the site, though they do so assuming young users can’t read or follow very basic instructions! Consider making it a little tougher. Don’t forget, some wee ones are learning how to swipe a tablet screen before they can walk!

Delete:

What seems so simple is often anything but. To put it mildly, not all delete functions are equal. From “no brainer” to “not an option,” here’s a look at our sliding scale when it comes to ease of deleting.

For some apps/websites, it was as easy as the click of a button. Take Quizlet.com for example. This educational website allows users to sign up and join study groups on a variety of topics. But when you’re done, you simply had to click the settings button in the top right corner, scroll down and hit delete.

Others required a multistep process that could involve emails and/or phone calls to the company. Buried in the middle of its privacy policy is the delete option for targeted game app Despicable Me: Minion Rush.

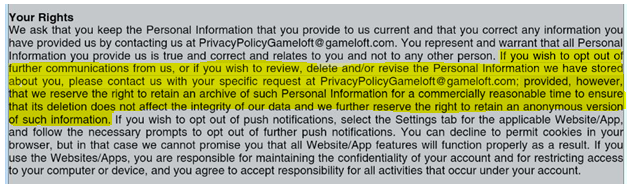

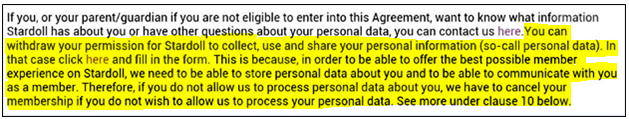

Stardoll.com, a website targeted at children that allows them to create dolls and interact with other users, requires parents/guardians to fill out a form. As you might be wondering from reading this excerpt from its privacy policy, it’s not clear whether the company actually destroys the personal information it has collected or whether it simply stops collecting, using and disclosing it to third parties. Given the amount of information this site collects and displays – country, gender, date of birth and anything through its free-text function – this raised some serious concerns for sweepers.

Unfortunately many popular websites and apps that collect personal information had no apparent means for deleting account data, leading our sweepers to believe that their information would be out there in the ether in perpetuity.

Off course:

It’s no surprise that kids like to click on shiny colourful things which many apps and websites have in spades. What’s not cool is when those shiny colourful things lead kids to places with different personal information collection practices or questionable content.

Redirection off-site often occurs through an ad or contest icon that sometimes appears to be part of the original site.

About a third of apps did not redirect users. Bravo! Meanwhile, 14 percent of them, including Barbie.com, at least provided a pop-up warning.

Others had more questionable redirection practices. For instance some websites/apps, including ones targeted directly at children, had ads for alcohol or dating websites that could lead users astray if clicked on. Some even had non-descript icons that, if clicked on, led sweepers to other sites that contained graphic and violent videos. Scary!

BONUS: Battle of the bands

Pop idols Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift and One Direction are all hugely popular among the under 12 crowd. But which fan site best bears that in mind when it comes to protecting the privacy of their youngest Beliebers, Swifties and Directioners?

Based on our indicators, here’s how these musical magnates stacked up.

Taylorswift.com collected username, email, full name, photo, date of birth, city, gender and occupation. There was also an unmoderated free-text function in which users could type in whatever they like. The site could display your username, photo and city. While the site attempted to block users under the age of 13, the measure could be easily circumvented by keying in a different date of birth. It also redirected visitors to a half dozen social media sites, the Google Play Store and another Taylor Swift shop that separately collects a whole host of personal information. Finally, according to the website’s privacy policy, users could “access, update or delete” personal information via email. It also noted this could be done via the “my account” area of the website. That would be great. Too bad we couldn’t actually find a delete button.

Justinbiebermusic.com could collect a fan’s first name, email, date of birth, postal code and country. It too barred users under 13 but that measure could be similarly circumvented. The site also had links redirecting users to a variety of music and social media sites, including the pop star’s Facebook fan page. To “correct, update, amend, delete/remove” personal information, users are asked to send a letter via snail mail to an address in California, or to fill out an online form. It said users could also do it through the member information page, but no such page could be found.

Onedirectionmusic.com, meanwhile, did not collect any personal information directly on site, though users could be redirected to a number of social media and music sites. The One Direction store, however, did collect a variety of personal information.

We are certainly not trying to create any “Bad Blood,” despite Taylor Swift’s lyrics, but it seems as though all three sites could use some helicopter parenting! That said, according to our final indicator, OPC sweepers said they were most comfortable with the One Direction site which seemed to hit the higher privacy notes of the three. Too bad the band has broken up:( Or so we think!

While we recognize that age verification can be tough as crafty kids have found clever ways around such mechanisms, we commend One Direction for simply limiting collection. Remember, don’t collect if you don’t have to. We also observed other sites that recognized a user’s URL and barred them from going back to the site and simply entering a different age for a period of time in order to gain access to the site. Others automatically redirected young users to a children’s version of the site. While many protective controls are seldom fool proof, we encourage developers to be creative and to find new ways of using technology to protect our most vulnerable.

Final thoughts . . .

As you can see, sweepers here at the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada found many great examples of websites and mobiles apps that do not collect personal information whatsoever. We believe there are many effective ways to at least limit collection.

When it comes to protecting the privacy of children online, everybody has a role to play. Children themselves need to be educated about digital privacy issues and the perils of sharing personal information online. Teachers and parents can help instill this knowledge and should themselves be aware of what sites and apps their kids are using and what types of information they are being asked to hand over. Finally, developers should be mindful of who their users are and limit, if not eliminate, the collection of personal information from children through the use of innovative privacy protective controls.

Once we’ve finished sorting through our results, in conjunction with our provincial and international partners who are doing the same, we will determine any appropriate follow-up action.

As with last year’s Sweep, our follow-up activities could include reaching out to organizations to inform them of our findings and making suggestions for improvements. We also have the option to pursue enforcement action.

By the way, we wrote to the companies mentioned in the blog before posting this to share our concerns. Past experience has shown that education and outreach alone can often go a long way towards effecting positive change for privacy.