You might recall, a few weeks back our Office led and participated in the first annual Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN) Internet Privacy Sweep.

We sought to replicate the consumer experience by spending a few minutes on each site, assessing how organizations communicated their privacy practices with the public. The sweep was meant to assess transparency online and was not an assessment of organizations’ privacy practices in general. It was not an investigation, nor was it intended to conclusively identify compliance issues or legislative breaches.

After searching over 300 sites that day, our Office is still poring over the reports we’ve created, but we wanted to share some of our preliminary results with you.

The good:

We found several positive examples of transparency when it came to sharing privacy practices. The best policies were oriented towards the consumer, providing information that real people would actually want to know and would find helpful. Here are a few of our favourites:

Tim Horton’s outlines the different types of personal information they collect and use in relation to a number of activities – for example, when people shop online, enter contests, or register for a payment card. Overall, we found their policy uncluttered and straightforward – click on the screenshot to read this excerpt:

Tripadvisor’s Privacy Policy takes the extra step of offering a detailed explanation of its Instant Personalization feature, which uses information provided by Facebook to give the user a more customized experience. Their explanation not only details what information is collected and how it’s used, but also provides instruction on how to enable or disable the feature – take a look at this screenshot:

Also going that extra step is Allstate, which has established an anonymous and confidential reporting system through a third party for its customers to report privacy breaches with discretion. Promoting and facilitating two-way communication about privacy with consumers is a key element of transparency, so it’s heartening to see that a company like Allstate is thinking about how their consumers might want to communicate with them about privacy concerns.

Privacy policies that cover both online and in-store practices made our list of bouquets as well. IKEA Canada’s privacy notice points out IKEA’s use of closed circuit television (CCTV) cameras in its stores and parking lots and references their separate CCTV Surveillance Policy, which can be obtained by contacting their privacy officer. Given that many stores and parking lots use CCTV monitoring technology, this example shouldn’t be as rare as it is!

The bad:

Approximately 20 percent of sites we reviewed either listed no privacy contact, or made it difficult to find contact information for a privacy officer.

For example several sites, including theloop.ca and tsn.ca, linked to Bell Media’s Privacy Policy which reads in part:

And that e-mail address is….?

Well, we couldn’t find it.

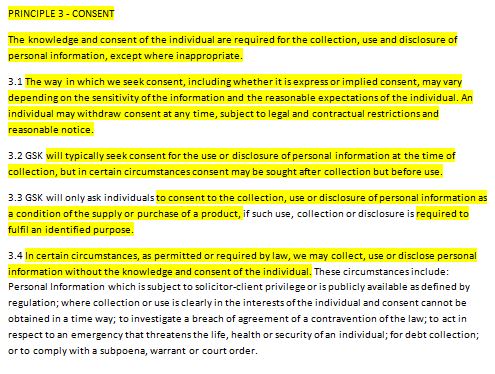

Many of the websites we looked at spent thousands of words regurgitating PIPEDA but providing very limited information of actual interest to readers. Just as the good examples made an effort to provide clear and useful information to the consumer, the not-so-good stuck to a more legalistic approach and merely claimed compliance to legislation.

For instance, take a look at GlaxoSmithKline’s explanation of how they seek consent for the collection, use and disclosure of individuals’ personal information, below. While their privacy policy hews closely to the language found in Canadian privacy legislation, it’s not all that helpful to a consumer who wants to know when their consent might be sought. We’ve highlighted the text that appears almost verbatim from Schedule 1 of PIPEDA :

Huh?

GlaxoSmithKline also offer readers an Internet privacy policy which, in some ways does a better job than their privacy code at explaining how a consumer’s information might be collected and used. However we found this policy, like others we saw during our sweep, focused on the use of cookies and other technical information collected via their site, while not providing enough information relevant to how the organization was collecting and using other types of information about the consumer.

The ugly:

About one out of every ten sites we looked at did not appear to have a privacy policy.

Another 10 percent had a privacy policy that was hard to find – sometimes exceedingly difficult to find, since it was buried in a lengthy Legal Notice or in the Terms and Conditions.

While almost 90 percent of the sites we swept had some sort of privacy policy or privacy notice, some policies offered so little transparency to customers and site visitors that the sites may as well have said nothing on the subject.

For example, A&W Canada, which collects personal information such as photos, addresses and dates of birth for various initiatives, has a 110-word privacy policy tacked on to the very end of the Terms and Conditions that offers nothing but a blanket promise of compliance with the law. While they do provide some other detail with respect to their privacy practices elsewhere on the site, and it is possible for visitors to their site to learn more by contacting their privacy officer through the e-mail address provided, we think organizations can do better. Individuals shouldn’t have to jump through hoops and provide their own personal contact information just to learn what an organization is going to do with their information.

Paternity Testing Centers of Canada, which collects and processes highly sensitive DNA samples of its clients, has a privacy statement so short it would fit in a tweet: “Paternity Testing Centers of Canada care about our clients and ensure that every test performed is strictly confidential.”

We wanted to provide you with some preliminary results that stood out to us from our sweep. Once we’ve completed a review of the results from our Office and the other jurisdictions that participated in the sweep, we will determine any appropriate follow-up action, in conjunction with our international sweep partners.