Report on the selection of the strategic privacy priorities

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

In the fall of 2014, Privacy Commissioner, Daniel Therrien, announced plans to engage with stakeholders across the country. The consultations would help shape the strategic privacy priorities that ultimately guide the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s work through to 2020.

The OPC held stakeholder meetings with individuals, consumer advocacy groups, industry and legal service providers, academia and government. They all noted their views on which privacy issues will be of greatest relevance to Canadians over the next five years. The OPC also undertook focus group research with Canadians to better understand their concerns and priorities.

Read the final report summarizing what the OPC heard and the priorities we chose.

Mapping a course for greater protection

June 2015

Commissioner’s message

The digital age has brought us vast economic and social benefits. From scientific innovation and market efficiencies to increased convenience and opportunities for individuals, our new-found ability to harness the power of information is transforming our world in many positive ways. Personalized health care, free online services, and real-time urban services like traffic management would not be possible without significant advancements in computing power and the capacity to store vast amounts of data and analyze it. On a more personal level, easy access to knowledge and effortless means of communicating with people around the globe are broadening our horizons.

At the same time, the pervasiveness of tracking individuals and their activities by commercial and government organizations threatens our deeply held notions of privacy. The government is collecting ever increasing amounts of data in support of national security initiatives with little oversight or transparency. In the private sector, mobile devices have greatly increased the amount and sensitivity of personal information being collected but these practices are generally opaque to consumers.

We find ourselves in a complex environment where we make daily tradeoffs between accessing digital services and keeping our information private, often without fully appreciating the nature of the exchange. When it comes to the government, we have no say in our information being collected. We can only trust government to be sensitive to our right to privacy in the course of improving service delivery and making public policy decisions.

The push to collect and process unprecedented amounts of personal information is posing great challenges to our existing frameworks for protecting privacy. For example, big data can lead to decisions about individuals based on inaccurate or incomplete information with no individual awareness or means to seek recourse. The risk of data breaches has risen considerably, calling for greater attention and ingenuity to be devoted to cybersecurity.

Uncertainty as to whether privacy is being adequately protected would have the effect of undermining trust in Canada’s technology sector as well as stifling business opportunities and innovation. It could also erode commerce and trade and hamper Canada’s ability to compete on the global marketplace. It would be in all our interests to ensure that Canada’s privacy protections remain relevant in the face of new and complex threats.

When I began my term as Privacy Commissioner of Canada, I said that my vision would be to improve the control Canadians have over their personal information. My arrival at the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada coincided with the Office’s planned initiative to refresh our strategic outlook to better align with the realities brought forth by our increasingly digital economy and society. This report summarizes the process we followed, the comments we heard from interested parties, and what we decided our priorities will be for the next few years. The new privacy priorities will help hone our focus to make best use of our limited resources, to further our ability to inform Parliamentarians, and to protect and promote Canadians’ privacy rights.

What we did

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) is required to carry out a mandate specified under the Office’s two enabling laws. The Privacy Act sets the ground rules for use of personal information by federal government departments. The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) applies to organizations engaged in commercial activities as well as to federal works undertakings or businesses. Our mandate includes investigating complaints from the public and responding to requests for information from Parliamentarians, and we will continue to carry out those activities.

That said, strategic privacy priorities will help us make choices that are discretionary in nature. For example, priority areas will help inform whether the Commissioner should initiate an investigation or audit where there are reasonable grounds to do so; which court actions we should intervene in; which speaking engagements we accept; what guidelines or research papers we should develop; what education or outreach efforts we undertake; and which research projects we should selectively fund under our Contributions Program.

In 2007, the OPC selected four strategic priorities to focus resources on the privacy challenges we identified as most pressing at that time. These were: information technology, public safety, identity integrity and genetic information. As we explained in our 2013 capstone report, this approach assisted the OPC in developing capacity, advancing knowledge, and effecting change.

Our main objective in setting new strategic priorities is to enhance Canadians’ control over their personal information. Being in control of one’s information is particularly challenging in a world of big data where an unprecedented amount of personal information is being collected and where powerful algorithms can detect patterns for a variety of purposes ranging from marketing to national security.

We wanted to ensure that the path to reaching this objective aligns with what is truly most relevant and of concern to Canadians. In order to find out what Canadians think about privacy and how privacy experts view the role of the OPC in the next five years, we set out to hear from a wide range of individuals and organizations about what privacy issues were important to them. We reached out to the general public across the country though public opinion polling as well as focus groups held from coast to coast. We also invited stakeholders, including representatives from the public and private sectors, academia, civil society, and consumer groups to attend facilitated discussions in five Canadian cities.Footnote 1

To provide a backdrop to the priority setting exercise, we proposed six potential privacy themes based on an environmental scan of the OPC’s current and past work, media reports and academic literature. We drafted background papers to describe the themes and attempt to capture the issues that, in our opinion, significantly affected Canadians’ privacy. The proposed themes and short summaries were as follows:

-

Economics of Personal Information

Online, there are innumerable services that we can access for “free” (e.g., email, search engines, and social media sites). The unstated business models underlying these transactions are premised on users trading their personal information (i.e. usage, contacts, interests, surfing experience etc.) for benefits or access to services. In essence, personal information has become a commodity—and finding ways to profit from our information has become big business. But what happens when privacy-protective alternatives become less readily available, either at exorbitant prices or get pushed out of the market altogether?

-

Government Services and Surveillance

Government is adopting new technologies and increasing information sharing between different departments, levels of governments and in some cases private-sector organizations, in a bid to improve programs and modernize service delivery to Canadians, while those same technologies are used to conduct more surveillance for program integrity, public safety and national security purposes. But at what point does enough, become enough, from a privacy perspective?

-

Protecting Canadians in a Borderless World

In a globally networked and integrated economy, personal information and data can move quickly and effortlessly around the globe, including in countries that have weak privacy protections or none at all, potentially compromising the privacy of Canadians abroad. How can we effectively protect personal data flows in a virtual world that knows no checks or borders?

-

Reputation and Privacy

The Internet has had a profound impact on personal reputation management. We ourselves create our online reputation by posting social media profiles, photos, online comments, etc. Our digital trails can also paint a picture of us, sometimes unbeknownst to ourselves, and others can shape our reputation as well. Once personal information makes its way online in one context, it can be extremely challenging to remove it or keep it from being used in different contexts. Though we grow and change over time, unfortunately the personal information we post online does not.

-

The Body as Information

The information generated by our bodies is uniquely personal, and as such it can be highly sensitive. As more and more information about our bodies is collected and digitized through wearable computing devices and connected with other online and offline information about us, the impacts on privacy can be profoundly game-changing. While we may seek out this information for our own medical or recreational purposes, what are the implications for our future insurability or employability?

-

Strengthening Accountability and Privacy Safeguards

As more and more information is collected, processed and stored electronically, organizations must take responsibility for their personal information management practices. They will have to find continually novel ways of updating privacy practices and security safeguards to protect themselves effectively against the growing proliferation of threats of loss, theft or misuse of information. Accountability and governance measures will become more important than ever.

In December 2014, we conducted eight focus groups with individual Canadians in Vancouver, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax. Participants were provided with summaries of the six proposed privacy themes and were prompted to discuss their views on privacy issues through a series of structured questions. In particular, they were probed for their awareness of the issues as well as their views on where the responsibility lies for protecting personal information—with individuals, organizations or government. We used the results of the 2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy, an OPC poll of 1500 Canadians about their understanding and awareness of privacy issues, to further inform our thinking on potential privacy priorities.

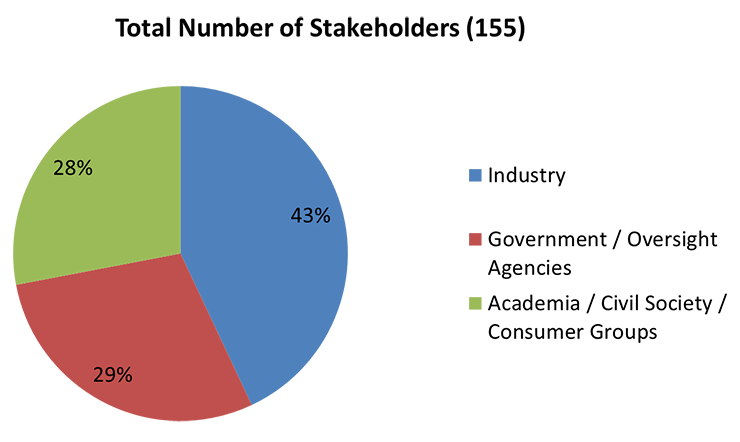

In January and February 2015, we held all-day meetings with stakeholders for an in-depth discussion of privacy issues as framed by the six proposed privacy themes. We invited a wide range of interests from across Canadian society so as to be able to hear a diversity of views and perspectives. Commissioner Therrien and OPC staff met with over 150 representatives (Figure 1) from academia, civil society, consumer groups, the private sector, and government, including provincial and territorial privacy oversight offices.

We also received seven written submissions from invitees who either could not attend or wanted to express their views in more detail. Stakeholder comments and opinions were invaluable in helping to shape and refine the privacy priorities we subsequently selected, and in helping focus our direction over the next few years.

Figure 1: Makeup of meetings by stakeholder group

Text version of Figure 1

Figure 1. Makeup of meetings by stakeholder group

| Type of stakeholder group | Total Number of Stakeholders |

|---|---|

| Industry | 43 |

| Government | 29 |

| Academia / Civil Society/Consumer Groups | 28 |

What we heard

“Canadians increasingly feel that their ability to protect their personal information is diminishing. Seventy-three percent, the greatest proportion since tracking began, think they have less protection of their personal information in their daily lives than they did ten years ago.”

- 2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy

Through our 2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy, we heard that Canadians’ concern with the use of their personal information was relatively high. Roughly half of polled Canadians admitted to not having a good understanding of what businesses and government do with their personal information. This concern was echoed by focus group participants, who repeatedly stated that they have no idea what happens to their personal information in the private and public sectors, and who can access it.

Both focus group and stakeholder meeting participants were asked to consider the responsibilities of individuals, organizations, regulators and legislators in protecting privacy, as well as to describe the role they feel the OPC should play to advance privacy.

Focus group participants generally felt that responsibility for privacy protection begins with them because for the most part they can choose what information to share and with whom. They believe organizations have an ethical and legal responsibility to protect the information they collect, while the government is responsible for developing, monitoring and enforcing laws.

Stakeholders varied in their responses about where the responsibility lies for protecting privacy. Some stakeholders indicated that individuals are responsible for learning about an organization’s privacy practices so that they are in a position to make informed choices with regard to their personal information and to provide meaningful consent. Others suggested that organizations play an important role in this process by being open and transparent about their information handling practices.

The OPC has traditionally been successful in working with organizations that are willing to comply and we plan to maximize the use of current legislation to help those organizations. This may include supporting “regulation-lite” options such as industry codes of conduct or ethical standards. However, we will also need to determine under what circumstances more powers are required, for example, when dealing with non-compliant organizations, in order to prescribe minimum expectations and possibly “no-go” zones.

Several ideas emerged through discussions that were common to most or all of the proposed themes. These can be summarized as follows:

- Vulnerable groups are particularly at risk of potential harms stemming from each theme. The groups described as “vulnerable” vary depending on the theme, but youth and seniors were mentioned frequently.

- Privacy enhancing technologies and privacy by design are necessary to reinforce privacy protections at the front end.

- The OPC has a significant role to play in education for individuals and Parliamentarians to raise their awareness of privacy issues. Similarly, organizations, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs), are in need of OPC outreach to reinforce understanding of their privacy obligations under PIPEDA.

- Increased offers to engage in discussions with stakeholders for the purpose of enhancing the OPC’s education, outreach, enforcement, and research activities.

- De-identification and anonymization are central to any privacy debate and more research and guidance are needed to provide clarity on preferred solutions.

- Cybersecurity is a top preoccupation for organizations, governments and individuals.

Economics of personal information

“All companies are becoming information brokers. A phone company is no longer just a phone company.”

-Stakeholder

“I’m OK with profit but tell me what’s happening with my information.”

-Focus group participant

“Most Canadians feel that it is at least somewhat likely that their privacy may be breached by someone using their credit/debit card (78%), stealing their identity (78%), or accessing the personal information stored on their computer or mobile device (74%).”

- 2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy

This proposed theme, along with “Government Services and Surveillance,” provoked the liveliest discussions both at the focus groups and stakeholder meetings.

Focus group participants expressed concern about not having enough control over their online information. They felt uninformed about what their personal information was being used for and by whom and felt privacy policies were generally incomprehensible. They were aware that free online services are offered in exchange for personal information, and that companies use the personal information they collect to offer personalized content such as customized marketing. Some were accepting of this practice while others felt that it should be possible to go online without having personal information collected and sold. Identity theft was overwhelmingly seen as the biggest threat of online activity.

Much of the stakeholder discussions focused on the value of personal information and the dynamics of the exchange individuals make when they share their personal information with organizations to obtain a product or service. Some felt that the power relationship between individuals and organizations was skewed in favour of industry, and since online engagement is becoming less of a choice for individuals, more regulation is needed over this commercial sphere. Others emphasized the benefits of the online business model to individuals and society such as access to free and innovative services, convenience, economic growth, fraud prevention, and economies of scale.

The efficacy and suitability of PIPEDA’s consent model was questioned in the context of big data, the Internet of Things, and the mobile environment. We heard near consensus that consent is not working in large part because insufficient information is provided to allow individuals to exert control and provide meaningful consent. Some felt that even if individuals were given more information, other measures, such as greater accountability and more robust governance processes, may be required in order for individuals to have greater control over their personal information. However, others were of the view that the consent model provides individuals with the right tools to exercise control, provided PIPEDA is used to its fullest in both spirit and intent.

Government services and surveillance

“Do we attain the benefit we are told we are getting (in exchange for our privacy)?”

-Stakeholder

“It’s up to the OPC to speak out against surveillance…the OPC should be out there banging the drums.”

-Stakeholder

Focus group participants for the most part were comfortable with surveillance for the protection of national security and crime prevention; however, when asked about surveillance being applied to them, many did not like the idea of being profiled without their knowledge and were concerned about how surveillance might infringe on basic rights and freedoms. They were comfortable with the government’s use of personal information to deliver more efficient services, though some worried about the government’s technical ability to safeguard information from breaches.

Stakeholders overwhelmingly felt that surveillance should be a priority area for the OPC. We heard many concerns about recent legislation, particularly relating to lawful access and anti-terrorism. Concerns were also voiced about the government’s massive data collection activities, as revealed by Edward Snowden, as well as the deputization of private sector companies to collect Canadians’ information on behalf of the government. Stakeholders felt that the OPC’s involvement in this area is crucial because Canadians do not have a choice in dealing with the government and the OPC is uniquely positioned to hold the government accountable for respecting Canadians’ privacy. Some expressed fears that vulnerable groups such as youth and minorities would be adversely affected by government profiling and surveillance activities.

Stakeholders were generally comfortable with sharing information for service delivery purposes and a clear majority felt that the OPC should focus on surveillance and not service delivery. We heard calls for greater transparency of government information sharing agreements in the context of national security activities, as well as warrantless access of telecommunications data. We were asked to advocate for more effective oversight of government surveillance activities.

Protecting Canadians in a borderless world

“Some companies are calibrating to the highest (privacy) standard and applying it internationally; others are choosing to locate in the country with lowest standard.”

-Stakeholder

Focus group participants were generally not comfortable with their personal information leaving Canada, and many were in fact surprised to hear that it routinely does. They perceived international laws to be less privacy protective, and felt that having their personal information leave Canada exposed them to an increased risk of fraudulent activities such as identity theft.

From stakeholders, we heard that the lack of harmonized privacy legislation internationally is challenging for organizations and confusing to Canadians. Organizations spoke about the costs of figuring out and keeping track of their legal obligations in different jurisdictions. Some noted the need for more transparency with regard to where Canadians’ data is stored and processed, and the level of protection that exists abroad.

The OPC was encouraged to continue its international cooperation and enforcement efforts. This was seen as crucial to having a voice on the international privacy stage, to protecting Canadians personal information abroad, and to being an effective overseer of multinational companies’ privacy practices.

Most agreed that this theme deserved considerable attention but felt it was a cross-cutting issue relevant to all priorities rather than a priority in and of itself.

Reputation and privacy

“You don’t build your reputation. Your reputation builds you.”

-Stakeholder

“You cannot remove it, ever. So if something goes up negatively, it never goes away.”

-Focus group participant

“Three-quarters or more of Internet users expressed some level of concern about the different ways the information available about them online might be used by organizations. At least four in ten, moreover, expressed a high level of concern (scores of 6-7 on a 7-point scale). Concern about personal information being used by companies to determine insurance or health coverage was highest, with exactly half expressing strong concern about this. Following this, 49% are very concerned about the impact on their personal reputation as more information is collected, assembled, and made into profiles about them.”

-2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy

Everyone we heard from was aware of the potential reputational harms resulting from sharing personal information online. Youth and seniors were seen to be most at risk, youth because they are early adopters of new technologies and seniors because of their relative inexperience with using online services. Many saw reputation as a larger ethical and digital literacy issue, with privacy as one component.

Focus group participants spoke about their lack of control over their personal information online. They were concerned with the permanence of online information; the lack of mechanisms for deleting or correcting information; and confusing privacy settings. While they accepted their responsibility for managing their online reputation, they felt that organizations should be doing more to help them in this regard by providing greater transparency and user-friendly privacy features.

Stakeholders expressed a range of views on the question of responsibility for individuals’ reputations. We heard from some that the OPC has mainly an educational role in this area, and that we should respect the right of individuals to make their own choices once they were sufficiently informed of the potential consequences of their actions. Others said that organizations bear some responsibility in helping individuals protect their reputations. The lack of tools to counteract digital memory and allow deletion or correction of information was cited as a problem. It was suggested that the OPC examine the “right to be forgotten” in the Canadian context, and give thought to the level of responsibility that should rest with organizations for dealing with objectionable information either posted to or surfaced by their platforms or services.

Profiling by organizations was also raised as an important issue under this theme. The potential for discriminatory practices, such as differential pricing, was noted as posing a significant risk of harm to individuals, particularly those in vulnerable groups.

Body as information

“My concern is whether they look at your medical history and reach conclusions. They form an idea, a prejudice. You can be denied employment.”

-Focus group participant

“With respect to emerging technologies or services that may present risks to Canadians' personal privacy, there was moderate, but widespread, concern about the following possibilities:

- 81%: results of genetic testing being used for non-health related purposes (…)

- 70%: wearable computers that collect personal information from the wearer”

-2014 Survey of Canadians on Privacy

This proposed priority area resonated more with stakeholders than it did with focus group participants, though both agreed that body-related information requires special privacy protections because of its sensitivity. Focus group participants had difficulty engaging with the topic and expressed a lack of first-hand knowledge of the issues.

Stakeholders viewed this as an emerging issue that the OPC should get ahead of to help proactively build in the appropriate privacy protections. Many stakeholders were very concerned with big data analytics being applied to this very sensitive information. They felt that the big data approach to health, genetic and biometric information has a high potential risk of harmful secondary uses ranging from marketing to insurance applications to uses we have not yet conceived of. The consent model was seen to be weak in this context, and it was suggested that appropriate uses of information may need to be legislated. Others saw the need for enhanced transparency to make individuals better aware of what information was being collected, by whom, and for what purposes. The privacy of vulnerable groups, such as those who are dependent on medical devices, was seen as being most at risk. Security was also viewed as a significant concern due to the sensitivity of the information and its attractiveness to criminals.

Finally, we were asked to recognize the benefits to individuals and society in our consideration of this theme. Some expressed a need for more research and guidance on de-identification and anonymization to aid researchers in harnessing the great value of this data in a privacy protective manner.

Strengthening accountability and privacy safeguards

“I sort of expect I could get hacked in using the Internet. I pick and choose the organizations I deal with and what I give them.”

-Focus group participant

“PIPEDA was meant to be the floor and has become the ceiling.”

-Stakeholder

“Most Canadians feel a greater reluctance to share their personal information with organizations in light of recent news reporting of sensitive information, such as private photos or banking information, being lost, stolen or made public. Seventy-eight percent said these incidents have affected their willingness to share personal information with organizations at least somewhat (scores of 3 or more), with three in ten (31%) saying their willingness has been affected a great deal.”

-2014 Survey of Canadians about Privacy

Discussions around this theme aligned very strongly with the OPC’s background paper. Focus group participants were generally quite concerned about the protection of their personal information by private sector organizations, and many said they were careful in choosing which organizations to interact with online. Many expressed a higher level of comfort in dealing with large organizations, particularly banks, because their banking information had never been compromised. They also expressed a desire for more transparency around private and public sector privacy practices.

Among stakeholders, accountability was seen as a bedrock issue that was the foundation of privacy compliance in all the proposed priority areas. It was generally felt that privacy laws were outdated, and that mandatory breach notification is crucial to accountability. Some called for an increased enforcement role by the OPC, for example, through more private and public sector audits.

Overwhelmingly, stakeholders called on the OPC to assist SMEs in meeting their privacy obligations. It was also suggested that accountability could be enhanced at the front end if the OPC were to reach out to the manufacturing sector to help engineers, technologists, and developers to integrate privacy by design principles.

What we decided

In choosing new privacy priorities for the OPC, we were guided by what we heard during our conversations with stakeholders and the general public. There was general agreement that the six themes we had suggested were all highly relevant, although two (“Protecting Canadians in a borderless world” and “Strengthening accountability and privacy safeguards”) were seen as cross-cutting strategies rather than priorities as such. We therefore made them horizontal strategies (see below), as well as three other approaches that emerged from our consultations: exploring innovative and technological ways of protecting privacy; enhancing our public education efforts; and enhancing privacy protection for vulnerable groups.

As a result, we have decided to concentrate our energies on four main priority areas:

- Economics of personal information;

- Government surveillance;

- Reputation and privacy; and,

- The body as information.

Plan of action

In addressing these priorities, we have decided on a results-oriented approach that maps out actions to focus on the short (1.5 years), medium (1.5 to 3 years) and longer term (4 to 5 years). In the short and medium terms, we will seek to better understand how privacy is implicated and to inform organizations, the public and Parliamentarians on the issues at stake. We will also issue discussion papers in the short term, seeking to engage Canadians on key privacy challenges before, in the medium term, we will identify potential solutions, apply those within our jurisdiction and be prepared to recommend legislative changes as appropriate. In the longer term, we will enforce these solutions by holding organizations accountable, we will evaluate compliance and we will adjust our approach as necessary.

Our plan of action reflects our preference for how issues should develop. However, we are keenly aware that at any time, there may be developments outside our control that require attention and resources, for instance government initiatives impacting privacy or the next legislated review of PIPEDA. With that caveat, our plan is outlined below.

Economics of personal information

As our personal information becomes increasingly monetized and serves as a new form of currency that drives our new digital economy, the incentive to collect and use it for new innovative purposes can barely be contained. Every day there are new, creative ideas on how businesses can derive more profit from our personal information and whole new business models are redefining our concept of commercial activity.

Individuals, left completely to their own devices, can hardly be expected to demystify complex business relationships and complicated algorithms to make informed choices about which companies they wish to do business with based on a clear calculus of risks and benefits. Time and again, we have heard individuals bemoan the fact that if they want to participate meaningfully as digital consumers and access new goods and services that have replaced older ones no longer available, they have no real choice other than to “close their eyes”, “block their nose” and click “I accept”.

A first goal for the OPC will be to enhance the privacy protection and trust of individuals so that they may confidently participate in an innovative digital economy. To achieve this, the OPC will strive through our investigative and research work to unpack, understand and make more transparent these new business models; through our technology lab, and working with technology associations, manufacturers and security experts, we will contribute to the development of creative and innovative privacy-enhancing solutions; through our guidance and outreach efforts, particularly aimed at SMEs, we will encourage organizations to explain the privacy implications of their new products and services in a language that individuals could more readily understand; through our internal research work and our Contribution Program, we will stay ahead of emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things and digital payment systems; through our compliance functions, we will complement our existing investigative powers under PIPEDA with alternative enforcement possibilities such as industry codes of practice and new compliance agreements made possible through Bill S-4.

Our policy work will help to build normative frameworks around new business models and will seek to identify enhancements to the consent model so that concerns raised both by individuals and organizations are addressed. In the short term, we will produce a discussion paper outlining challenges with the current model, suggesting potential solutions (including self-regulation, greater accountability and enhanced regulation), and seeking to clarify the roles of individuals, organizations, regulators and legislators. We will then engage stakeholders. In the medium term, we will identify improvements, apply those within our jurisdiction and be prepared to recommend legislative changes as appropriate.

Government surveillance

There is no doubt we live in a different world than we did fifteen years ago. The Commissioner’s own professional background as a senior justice lawyer working in Public Safety and National Security portfolios has sensitized him to the real risks we face with escalating and distributed threats of terrorism. No one would contest the need to protect the safety of our citizens. Canadians want to be and feel secure, but not at any and all costs to their privacy—particularly when it comes to their own privacy. What they want is a balanced, well-measured and proportionate approach. It has become far too naive to believe that only “bad people’s” privacy is at stake or “if we have nothing to hide, we have nothing to fear”. For we now know that in order to identify people who pose risk of terrorism, all Canadians are potentially under scrutiny. Sometimes, tragic mistakes are made and subtle—or not so subtle—forms of racial discrimination result. As public reaction to Bill C-51 has recently shown us, we are all now caught in this web and our interests, activities, and sanctity of our innermost thoughts are at stake.

A second goal for the OPC will be to contribute to the adoption and implementation of laws and other measures that demonstrably protect both national security and privacy. In the short term, through timely and useful advice on Privacy Impact Assessments, Information-Sharing Agreements and regulations, we will seek to reduce the privacy risks associated with the recently adopted Anti-terrorism Act, 2015. As regards the lawful access provisions of Bill C-13, we will work with others and provide guidance to both public and private sectors to establish standards for transparency and accountability reports related to the communication of personal information by companies to law enforcement agencies. In the short and medium terms, we will examine and report on how national security legislation such as Bill C-51 is implemented. We will use our review and investigative powers to examine the collection, use and sharing practices of departments and agencies involved in surveillance activities to ensure that they conform with the Privacy Act. We will report our findings to Parliamentarians and the public, and issue recommendations for potential improvements to policies or legislation, as warranted.

Reputation and privacy

With the advent of social media and new communication technologies, things we may have said or done in the past, once regretted but long since moved on from, are now capable of being indefinitely captured, shared beyond our span of control, and brought up again completely out of context—sometimes with devastating consequences. What others post about us, sometimes malevolently, or sometimes for well-intentioned purposes (open courts, journalistic, open government, archival etc.) may be very difficult to have taken down. The whole world is grappling with the implications of a net that never forgets and the long term impacts this will have on our human behavior and our human relationships.

What we think, what we read, what we search, where we are, what we buy—once our own business, is now everyone’s business. Organizations and governments amalgamate our digital trails in order to create profiles about us, make inferences about our interests, categorize us in terms of potential risk and predict our future behaviour. Who we really are as persons is taking a backseat to who others think we are. Our digital selves are assigned to groups and related assumptions about such groups—a practice which some may find in and of itself offensive, let alone the unfair consequences that may result.

A third goal for the OPC will be to help create an online environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment. In the short term, we plan to launch a dialogue on reputation and privacy, starting with a research paper. In the short and medium terms, through in-house research and the Contributions Program, we will advance knowledge and understanding of online reputational risks; we will develop a policy position on potential recourse mechanisms, such as the right to be forgotten in the Canadian legal context; working with technology associations and manufacturers, we will contribute to possible technological solutions such as privacy by obscurity, anonymization or automatic deletion options; through our education and outreach efforts, and in collaboration with key partners, we will help improve digital literacy particularly among vulnerable populations, including the young and the elderly; through our investigations, we will get to the root of some of the reputational issues complainants are most concerned about, and help shape organizational practices through our remedial recommendations and court enforcement, as needed.

The body as information

There was a time when the concept of privacy, at least legally speaking, was understood as engaging one of three distinct zones of privacy: informational privacy, bodily privacy and territorial privacy. With the advent of wearable computing and bodily tracking devices, these distinctions have become increasingly blurred. As the connections between information technology, geo-location technology and the human body become integrated through smart devices and the Internet of Things (and people), personal information has become more intimately sensitive than ever and the potential privacy incursions may become greatly amplified. The exploitation of this information for commercial profit-making motives or to assist government surveillance efforts, may adversely affect not only our right to privacy in respect of our personal information, but our bodily integrity and our very dignity as human beings.

Our fourth goal is to promote respect for the privacy and integrity of the human body as the vessel of our most intimate personal information. In the short term, we will conduct an environmental scan of new health applications and digital health technologies being offered on the market and research their privacy implications. In the medium term, we will provide guidance, particularly to SMEs and app developers, on how to build privacy protections into their new products and services while avoiding certain “no-go” zones altogether; through our education and outreach efforts, we will help inform Canadians about the privacy risks associated with wearable devices and direct-to-consumer genetic testing, and offer options for protecting themselves; we will work with government departments to maximize the potential, and minimize the risks, associated with new forms of biometrics.

We will have pursued our stakeholder dialogue with the insurance industry in the short term, and then with other secondary users of personal information in order to balance the business need for personal information about health and body with people’s right to have their privacy respected without adverse economic impact on them or their families.

Figure 2: Implementing the privacy priorities

The following illustration maps out how we plan to implement these new priorities.

| Priorities | ECONOMICS OF PERSONAL INFORMATION | GOVERNMENT SURVEILLANCE | REPUTATION & PRIVACY | THE BODY AS INFORMATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals | The OPC will have enhanced the privacy protection and trust of individuals so that they may confidently participate in an innovative digital economy. | The OPC will have contributed to the adoption and implementation of laws that demonstrably protect both national security and privacy. | The OPC will have helped to create an environment where individuals may use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment. | The OPC will have promoted respect for the privacy and integrity of the human body as the vessel of our most intimate personal information. |

| Strategies for achieving our goals | Exploring innovative and technological ways of protecting privacy | |||

| Strengthening accountability and promoting good privacy governance | ||||

| Protecting Canadians’ privacy in a borderless world | ||||

| Enhancing our public education role | ||||

| Enhancing privacy protection for vulnerable groups | ||||

Strategic approaches

Now some of you may find these goals to be ambitious. Indeed they are—as are we about what our Office will be able to accomplish over the next few years. But we are also concrete and realistic. In order to have any chance of succeeding and achieving real positive impact, I believe we will have to be highly strategic in our approach.

Exploring innovative and technological ways of protecting privacy

First, to be clear, our objective is not to stop innovation, but in fact, to help enable its progress in a manner which is responsible and respectful of people’s privacy. We are mindful that a thriving Canadian economy must remain globally competitive and Canadians want to benefit from new products and services and efficient government services. But so too are we mindful of the need to keep privacy costs down. In order to keep step with innovation and to help shape and influence its direction through credible and helpful advice, the OPC too has to be innovative. We ourselves need to stay at the cutting edge and think ahead to explore innovative ways of protecting privacy—be they through creative concepts and ideas, or novel technological solutions.

Strengthening accountability and promoting good privacy governance

Second, in order to successfully deliver on these four goals, and ultimately, our overarching vision of enhancing Canadians’ control over their personal information, the OPC will have to take a broader approach to promoting good privacy governance. While “individual control” may conjure up the concept of informed consent—which is certainly a key part of it—we do not believe consent can solve it all. We have heard time and again, that consent forms are sometimes used unfortunately as a means of waiving away rights and protecting against liability, rather than achieving true individual agency. Or when it comes to government, there is no possibility for consent at all. Yet, despite this, individuals can have—and feel—greater control over their personal information, if they themselves play a more active role in protecting their own privacy wherever possible, or if they can be confident in the overall accountability and governance measures organizations put in place to protect their personal information.

Protecting Canadians’ privacy in a borderless world

Third, we are also fully aware that to succeed in achieving our four goals, we simply cannot do it alone. It may be trite to say that personal data knows no boundaries in today’s global world. Particularly since the advent of the Internet, personal data cannot be simply contained and regulated in bubbles. While most Canadians may intuitively understand that personal information is permeable and may cross borders, our focus groups revealed that not all Canadians fully appreciate just how far it may travel. As the courts have told us, our Office’s job is to protect Canadians’ privacy, whether their personal information resides in Canada, or in some cases, elsewhere in the world.

To do so effectively, we must continue to build on our provincial, territorial and international relationships and networks. We must continue to work collaboratively with our international enforcement partners to coordinate our investigations and leverage our resources. And we must continue to participate in, and where appropriate, lead, on developing and harmonizing international policy positions on key issues.

Enhancing our public education role

Fourth, we will enhance our public education role with respect to each of the four priorities. Focus group participants and stakeholders alike told us that more public education is needed. We heard that Canadians consider us a trusted voice for helping individuals better understand and exercise their rights, and organizations to better understand their privacy responsibilities. While this has long been a focus for our Office, as the scope and complexity of privacy issues grows, we recognize that we need to do even more in this area, and to find new ways to reach out to Canadians and organizations. We will intensify our efforts to ensure that material we create for and make available to the public is practical and easy to use. We will focus on ensuring that our website, as our key communications vehicle, is designed from the user’s perspective, to make certain that individuals and organizations can find the information they need. We will also look for opportunities to reach out further to new audiences that may be in particular need of privacy education—for example, vulnerable groups, such as seniors, as well as small businesses.

Enhancing privacy protection for vulnerable groups

Finally, recognizing the OPC’s mandate to protect the privacy rights of all Canadians, we will not be truly successful unless we include all Canadians. We heard from both stakeholders and focus groups that some groups are particularly at risk from privacy threats posed by private and public sector activities. For example, young people face enhanced reputational risks as a result of the nature and vastness of the personal information they share online; new Canadians may be at increased risk of targeting by national security initiatives. We intend to focus our efforts on protecting vulnerable populations, acknowledging the intellectual, physical, cultural and linguistic barriers that impede Canadians’ ability to exercise meaningful control over their personal information. We plan to work with them and others to reduce those barriers, which may mean expanding our traditional network of partners and stakeholders to include new groups, initiating education and outreach efforts focused on particular audiences, and prioritizing investigations that give voice to our most vulnerable.

Conclusion

The priority setting process has been both interesting and inspiring for our office. We would like to acknowledge the contribution of stakeholders and focus group participants who took the time to participate and share their views with us. We now have a broader understanding of different groups’ concerns, providing a better sense of where we should focus our efforts to make best use of our resources and, as an organization, make important decisions about our proactive work.

Having identified the OPC’s priorities and having set clear goals, we are eager to begin working collaboratively to advance these issues for the benefit of all Canadians. The road ahead is exciting, and over the next five years, Canadians should expect to see and hear more about our efforts to help enhance their privacy in the digital age.

Alternate versions

- PDF (541 KB) Not tested for accessibility

- Date modified: