2020-21 Departmental Results Report

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

(Original signed by)

The Honourable David Lametti, P.C., Q.C., M.P.

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2021

Catalogue No. IP51-7E-PDF

ISSN 2560-9777

Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

From the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Departmental Results Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2021.

Fiscal year 2020-21 was an important year in many respects. We continued to adapt to the challenges posed by what was clearly becoming a long-term pandemic. We were able to put budgetary increases to work and saw the tabling of a bill in the private sector and a consultation document in the public sector.

Fiscal year 2020-21 was an important year in many respects. We continued to adapt to the challenges posed by what was clearly becoming a long-term pandemic. We were able to put budgetary increases to work and saw the tabling of a bill in the private sector and a consultation document in the public sector.

The pandemic had an impact on OPC operations, as it did across the federal government and the private sector. The OPC had to quickly adapt its processes to continue serving Canadians and supporting its internal programs during the pandemic. In this regard, we were able to rise to the challenge and remain fully operational by working remotely.

The permanent funding increase in the 2019 federal budget allowed us to expand our policy and guidance functions, enhance our advisory services for organizations, and address pressures resulting from new mandatory breach reporting requirements in the private sector.

The temporary funding we received also helped us reduce a very large part of our investigative backlog of complaints older than a year. This allowed us to slightly exceed our target of 90%, reducing the overall backlog by 91%.

Over the past year, we have undertaken a number of initiatives to improve the protection of Canadians’ personal information, and promote a better understanding of the rights and obligations of individuals and organizations under federal privacy legislation.

Notably, we updated guidance for federal institutions on privacy impact assessments and published guidance on protecting privacy during a pandemic, including a contextual framework for government institutions to protect privacy in the context of COVID-19 initiatives. We continued to provide advice to Health Canada on the COVID Alert exposure notification app to ensure it respects privacy and recommended that its use continue only so long as it is deemed to be effective in reducing virus transmission.

For the private sector, we developed guidance on the Internet of Things, updated our Privacy Guide for Businesses and produced our first breach record inspection report in response to new breach record-keeping obligations under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

The year 2020 also marked a milestone for privacy protection in Canada.

The OPC has long argued that stronger laws are needed to address privacy in both the public and private sectors. We have called for rights-based legislation that will support responsible innovation, and encourage trust in government and business activities.

Last fall, the federal government tabled Bill C-11 to reform Canada’s private sector privacy law. In addition, the Department of Justice launched a public consultation on modernizing the public sector Privacy Act.

We believed Bill C-11, which died on the order paper when a federal election was called in August, represented a step backward from current private sector legislation. Our detailed submission to Parliament contained numerous recommendations to improve the bill. The government seemed open to changes we proposed and I am hopeful that Canada will move in the direction of other jurisdictions, where privacy is not viewed as an impediment to innovation.

We are more optimistic about the proposals to update the Privacy Act. We believe they would lead to meaningful reform and align Canadian law with modern data protection norms in the public sector.

While we must wait to see how the newly formed government will proceed, these initiatives give us a better idea of the changes we can expect and what they will mean for the OPC in the near future. In particular, we expect our mandate to expand and our work, structure and scale to evolve.

As we look to the future and the eventual introduction and implementation of modern legislation, we have begun to study how we will adapt to our new roles and responsibilities. While the digital revolution offers important benefits and opportunities for government and businesses, it cannot come at the expense of privacy. We look forward to modern laws that will allow us to better address the privacy risks posed by new technologies and ensure that the OPC is equipped to act effectively as a regulator.

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Results at a glance

Actual spending

$31,810,835

Total actual spending in 2020-21

Actual full-time equivalents (FTEs)

212

Actual FTEs in 2020-21

Results Highlights for 2020-21

- The OPC was able to quickly and effectively meet the challenge of the pandemic by shifting nearly its entire staff to remote work and adapting its processes to continue serving Canadians.

- Over the past year, the OPC provided advice and issued recommendations to improve the various proposed reforms to federal privacy legislation in both the public and private sectors.

- The OPC had a positive influence on the development of the COVID Alert app and on other pandemics-related initiatives, thereby enhancing the protection of Canadians’ personal information.

- The OPC slightly exceeded its objective of reducing the investigative backlog of complaints older than a year by 90%, achieving a 91% reduction.

For more information on the OPC’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section in this report.

Results: what we achieved

This section describes, for each core responsibility, the results that the OPC achieved in 2020-21 and how OPC performed against the targets it set in its Departmental Plan for that year.

Core Responsibility

Protection of privacy rights

Description

Ensure the protection of privacy rights of Canadians; enforce privacy obligations by federal government institutions and private-sector organizations; provide advice to Parliament on potential privacy implications of proposed legislation and government programs; promote awareness and understanding of rights and obligations under federal privacy legislation.

Results

The 2020-21 fiscal year marks the third year of implementation of our Departmental Results Framework. The results are set out below.

Departmental result 1: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

The OPC’s primary goal is to protect the privacy rights of Canadians. A measure of our success is the proportion of Canadians who feel that their privacy rights are respected. Over the past year, we validated this estimate through a survey that included questions aimed at determining whether Canadians felt that businesses and governmental institutions respected their privacy rights. The survey results indicate that 45% of Canadians feel that businesses generally respect their privacy rights, and 63% feel the same about the federal government, an increase of 7% and 8% respectively, since 2018. While these results point to slightly more trust in businesses and the federal government, they are still far from our target of 90%.

With the temporary funding received in the 2019 federal budget, and through a continued focus on process improvements, the OPC was able to slightly exceed its 90% target for reducing the overall backlog of complaints older than 12 months, achieving 91% by March 31, 2021.

While our target was 75% in 2020-21, we resolved only 44% of all our complaints within service standards. In fact, the closure of a considerable number of aging files affects the results for this indicator by increasing our average complaints processing time.

The OPC also measures the percentage of recommendations accepted and implemented by federal institutions and private sector organizations in a compliance context. Over the past year, there was a 5% reduction in the proportion of recommendations accepted, which fell from 80% to 75%. On the public sector side, these figures reflect our observation that institutions do not always strive to respond to privacy requests from individuals in a timely manner, even following OPC intervention. We therefore encourage public-sector institutions to respond to these requests within an appropriate timeframe. There were also fewer recommendations accepted by private sector organizations, regardless of the type of complaint. This is concerning as our only recourse when our recommendations are not accepted is to go to the Federal Court. This forces us to make difficult decisions in a context of limited resources.

It should be noted that this result only speaks to privacy concerns that our Office becomes aware of through complaints. The OPC maintains that fundamental changes to our laws are required to protect Canadians and restore balance in their relationship with organizations. Robust privacy laws are key to promoting trust in both government and commercial activities, and without that trust, innovation, and growth can be severely affected.

Departmental result 2: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

A key first step to empowering Canadians to exercise their privacy rights is awareness. The results from our most recent public survey indicate that the level of awareness of privacy rights is still not at the level our office would like to see. Close to two thirds of Canadians rated their knowledge of privacy rights as good (64%). However, nearly one in five Canadians (18%) deemed their knowledge of this right to be poor or very poor.

If we compare these results with previous surveys of Canadians conducted in 2016 (65%) and 2018 (64%), we can see that the proportion of people who are aware of their privacy rights has not changed. Our objective of reaching 70% is, in our view, rather modest when assessed in the context of the necessity, in today’s digital world, for individuals to understand the privacy implications of the technologies they rely on to go about their daily lives. We hope that the outreach efforts we do through communications and public education activities, new or updated information and guidance, as well as some enhancements to our website, which are admittedly modest given our resources, will help move us closer to that target.

In implementing our Departmental Results Framework in 2018-19, our Office set a goal of issuing guidance on 90% of our list of 30 key privacy issues by March 31, 2021. Unfortunately, our Office was unable to make significant progress towards achieving this target in 2020-21. In the last year, the government launched two initiatives to reform federal privacy legislation. Considering the possibility of a transformed legal framework and the fact that our guidelines are grounded in legislation, we reoriented our work and allocated resources to analyzing and developing recommendations for legislative reform rather than issuing guidance that could quickly become outdated following such reform. In addition, the OPC had to be flexible and adapt to the unexpected effects of the pandemic. In this regard, we refocused our efforts on writing essential guidance documents on privacy during pandemics, such as A Framework for the Government of Canada to Assess Privacy-Impactful Initiatives in Response to COVID-19. Accordingly, in 2020-21 we were able to complete only one guidance document (Internet of Things) from our list of 30 key privacy issues. Overall, we issued guidance on 30% of our planned list, which is well below our 90% objective. As this indicator has now expired, the OPC will be working in the coming year on developing a new mechanism to define and direct our future guidance work for businesses and Canadians.

Our Office also updated and issued supplementary guidance to expand on some of the 30 key issues for which we had previously issued guidance. In addition, we drafted and updated a number of guidance documents, including How to stay safe when online gaming and the Privacy Guide for Businesses. We also published our first breach record inspections report.

The OPC’s website is the primary communication channel between the organization and Canadians. Overall, 74% of those who responded using the web-based feedback tool found the information to be useful. However, only a minority of web visitors provided feedback. More attention is given on qualitative feedback, which allows us to better understand Canadians’ needs and to update our webpages accordingly.

Departmental Result 3: Parliamentarians and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

The last year was rather unusual in terms of parliamentary activity. Since Parliament’s primary concern was to help Canadians through the pandemic, no bills or studies on which the OPC provided recommendations were adopted during 2020-21. However, we carried out a great deal of work regarding privacy law reform. Notable examples are our submissions on the review of the Access to Information Act and the modernization of the Privacy Act in the public sector. Finally, we also analyzed Bill C-11 regarding privacy in the private sector and presented an accompanying submission.

The OPC continues to proactively work with Parliament and in response to questions, bills and studies to improve legislative proposals to ensure that modern privacy legislation acknowledges and protects Canadians’ right to privacy and encourages responsible innovation.

On the private sector side, our Office carried out a range of compliance promotion activities, including advisory engagements. These activities are meant to engage businesses proactively to help guide them so that they can meet their privacy obligations. In all, our Office conducted 35 advisory engagements and 18 consultations, mainly with small and medium-sized businesses.

We also continued our efforts to build on the capacity of our technology laboratory to adequately support the Office’s research and investigation activities. We completed a thorough upgrade of the lab’s information technology infrastructure and acquired new state-of-the-art tools, which contributed to strengthening the Office’s technical credibility and influence, including our participation, as a technical authority, in the evaluation of an innovation within the Innovative Solutions Canada program of the Department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development.

In addition to the guidance work described earlier in this section, we have also worked to implement our multi-year communications and outreach strategy to increase businesses’ awareness of privacy obligations. The material published on our website aimed specifically at organizations, such as guidance documents, interpretation bulletins and case summaries, generated more than 670,000 visits in 2020-21.

On the public sector side, our Office continued to review a large volume of privacy impact assessments (PIAs) and consultation requests proactively made by federal government institutions. In 2020-21, we received 109 proactive consultation requests, a 65% increase from the previous year. In addition to the requests we received, we fully updated guidance for federal institutions and published guidance documents on privacy during a pandemic, as well as a contextual framework to help government institutions protect privacy amid COVID-19 initiatives. Using the framework, we reviewed the COVID Alert app and advised the government in this regard.

The OPC strives to provide advice and guidance documents for federal and private sector organizations that help them comply with their privacy obligations. We formally assessed organizations’ level of satisfaction with OPC guidance. For the third consecutive year, we have met our objective of 70% satisfaction among federal and private organizations concerning the usefulness of guidance documents on our website.

Results achieved

The summary table below provides an overview of the results achieved against our targets set in our Departmental Results Framework in effect since 2018-19.

| Departmental Results | Performance Indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2018-19 Actual results |

2019-20 Actual results |

2020-21 Actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met. | Percentage of Canadians who feel that businesses respect their privacy rights. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 38% | Not a survey year | 45% |

| Percentage of Canadians who feel that the federal government respects their privacy rights. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 55% | Not a survey year | 63% | |

| Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards. | 75% | March 31, 2021 | 50% | 61% | 44% | |

| Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations. | 85% | March 31, 2021 | 96% | 80% | 75% | |

| Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights | Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights. | 70% | March 31, 2021 | 64% | Not a survey year | 64% |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 27% (8/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 30% (9/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | |

| Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful. | 70% | March 31, 2021 | 72% | 71% | 74% | |

| Parliamentarians, and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights | Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted. | 60% | March 31, 2021 | 35% (33 recs made, 11 adopted) | 68% (28 recs made, 19 adopted) | n/aFootnote 1 |

| Percentage of private sector organizations that have good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations. | 85% | March 31, 2022 | Not a survey year | 85% | Not a survey year | |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 27% (8/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | 30% (9/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | |

| Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance. | 70% | March 31, 2021 | 73% | 71% | 70% |

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2020-21 Main Estimates |

2020-21 Planned spending |

2020-21 Total authorities available for use |

2020-21 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2020-21 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21,700,691 | 21,700,691 | 23,608,221 | 23,003,685 | 1,302,994 |

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2020-21 Planned full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Actual full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 159 | 158 | (1) |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s Program Inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are:

- Acquisition Management Services

- Communications Services

- Financial Management Services

- Human Resources Management Services

- Information Management Services

- Information Technology Services

- Legal Services

- Materiel Management Services

- Management and Oversight Services

- Real Property Management Services

At the OPC the communications services are an integral part of our education and outreach mandate. As such, these services are included in the Promotion Program. Similarly, the OPC’s legal services are an integral part of the delivery of compliance activities and are therefore included in the Compliance Program.

Results

Internal services continued to provide high-quality and timely advice and services to the entire organization in order to support OPC objectives, and enabled the Office to meet its administrative obligations.

In 2020-2021, these services played an essential role in supporting and ensuring compliance with numerous initiatives, including specifically:

- Enabling all OPC employees to work remotely as the entire organization seamlessly transitioned to functioning virtually by using IT innovations and solutions and adapting to the extraordinary circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Implementing up-to-date information management and IT strategies to maintain solid IT infrastructure and ensure that systems and services continue to meet our needs.

- Implementing the 2020-2023 multi-year strategic HR plan to effectively support the organization in carrying out its mandate. As a result of this plan, current and future employees will have the skills and competencies necessary to thrive in a competitive, flexible, agile and rapidly changing environment.

- Helping implement various initiatives and measures of the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) aiming to stabilize the pay system and minimize impacts on employees. The OPC is an integrated organization with compensation advisors on site, and therefore is not served by the Pay Centre in Miramichi. Although the pandemic required the compensation team to work remotely without notice, members were nonetheless able to keep pay transactions up to date and pay out retroactive adjustments.

- Progressively enacting revised Treasury Board policies as part of the Treasury Board Policy Reset Initiative. This includes all revised policies on people and executive management as well as related directives, mandatory procedures and standards.

- Performing the activities and applying the priorities set out in the OPC Departmental Security Plan in order to comply with the requirements of the new Policy on Government Security and meet the security objectives of the Plan.

- Implementing the Workplace Harassment and Violence Prevention Policy, which incorporates the requirements of the Canada Labour Code and the Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations. Employee learning plans have been modified to comply with these new requirements.

- Carrying out preparations for the public service-wide Classification Program Renewal Initiative and implementing changes to the Computer Systems (CS) occupational group through a classification conversion exercise.

- Pursuing collaboration and business partnerships with other small and medium-sized organizations and agents of Parliament to gain effectiveness, share tools and resources and, implement best practices in areas such as information technology, administrative services, finances, people management and human resources programs.

Budgetary financial resources (dollars)

| 2020-21 Main estimates |

2020-21 Planned spending* |

2020-21 Total authorities available for use |

2020-21 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2020-21 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7,961,195 | 7,961,195 | 8,999,819 | 8,807,150 | 845,955 |

| * Includes Vote Netted Revenue authority (VNR) of $200,000 for internal support services to other government organizations | ||||

Human resources (full-time equivalents)

| 2020-21 Planned full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Actual full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 54 | 54 | 0 |

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

Actual expenditures

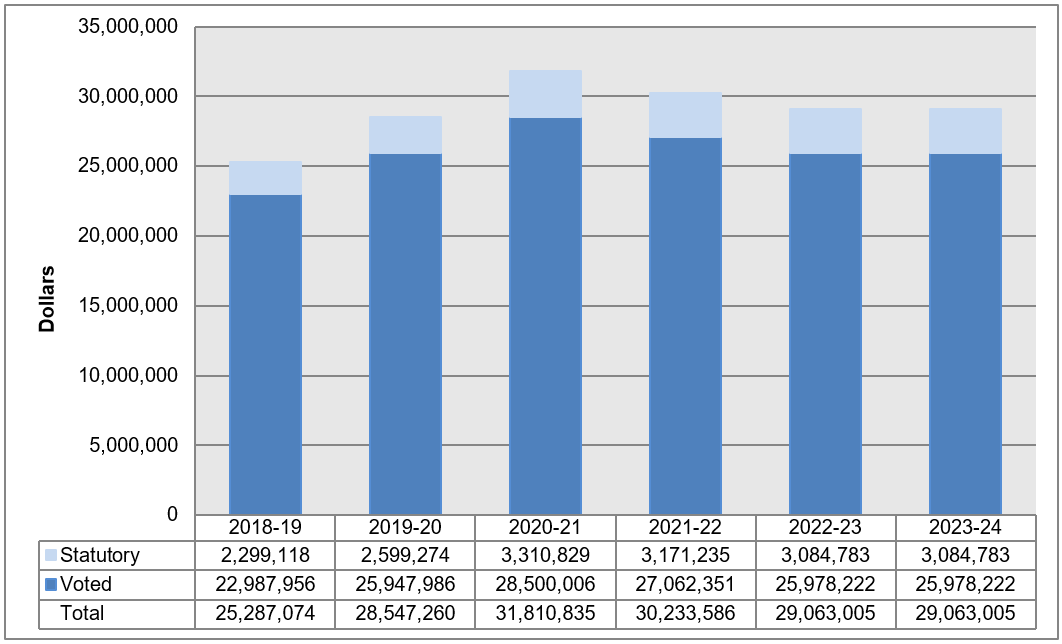

OPC’s spending trend graph

The following graph presents planned (voted and statutory spending) over time.

Text version of Figure 1

| Fiscal year | Statutory | Voted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 2,299,118 | 22,987,956 | 25,287,074 |

| 2019-20 | 2,599,274 | 25,947,986 | 28,547,260 |

| 2020-21 | 3,310,829 | 28,500,006 | 31,810,835 |

| 2021-22 | 3,171,235 | 27,062,351 | 30,233,586 |

| 2022-23 | 3,084,783 | 25,978,222 | 29,063,005 |

| 2023-24 | 3,084,783 | 25,978,222 | 29,063,005 |

The above graph illustrates the OPC’s spending trend over a six-year period from 2018-19 to 2023-24. Fiscal years 2018-19 to 2020-21 reflect the organization’s actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts. Fiscal years 2021-22 to 2023-24 represent planned spending.

As indicated above, there was a steady increase in spending from 2018-19 to 2020-21: OPC spending rose by $6.5 million in this period. This increase is primarily explained by the funding allocated to deliver the Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the Privacy of Canadians. The Office received funding to enhance its capacity, including its ability to engage with Canadian individuals and businesses, address complaints and respond to privacy issues as they occur. The increase can also be attributed to additional spending on staffing resulting from new hires, salary increases and retroactive payments made following the ratification of collective agreements over the past year.

Starting fiscal year 2021-22, OPC’s planned spending will decrease due to the sunset funding received in 2019-20 and 2020-21 to reduce the backlog of privacy complaints older than one year, and give Canadians more timely resolution of their complaints.

Budgetary performance summary for Core Responsibilities and Internal Services (dollars)

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2020-21 Main Estimates |

2020-21 Planned spending |

2021-22 Planned spending |

2022-23 Planned spending |

2020-21 Total authorities available for use |

2018-19 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2019-20 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2020-21 Actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection of privacy rights | 21,700,691 | 21,700,691 | 22,261,717 | 21,410,705 | 23,608,221 | 18,504,642 | 20,573,425 | 23,003,685 |

| Subtotal | 21,700,691 | 21,700,691 | 22,261,717 | 21,410,705 | 23,608,221 | 18,504,642 | 20,573,425 | 23,003,685 |

| Internal Services | 7,961,195 | 7,961,195 | 7,971,869 | 7,652,300 | 8,999,819 | 6,782,432 | 7,973,835 | 8,807,150 |

| Total | 29,661,886 | 29,661,886 | 30,233,586 | 29,063,005 | 32,608,040 | 25,287,074 | 28,547,260 | 31,810,835 |

For fiscal years 2018-19 to 2020-21, actual spending represents the actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts of Canada. Fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23 represent planned spending.

The net increase of $2.9 million between the 2020-21 total authorities available for use ($32.6 million) and the 2020-21 planned spending ($29.7 million) is mainly due to funding received for the operating budget carry forward exercise, compensation related to the new collective bargaining and adjustments to the employee benefit plans.

Total authorities available for use in 2020-21 ($32.6 million) compared to 2020-21 actual spending ($31.8 million) resulted in a lapse of $0.8 million. This amount represents the operating lapses reported in the Public Accounts of Canada by the OPC.

Actual human resources

Human resources summary for Core Responsibilities and Internal Services

| Core Responsibility and Internal Services |

2018-19 Actual full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Actual full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Planned full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Actual full-time equivalents |

2021-22 Planned full-time equivalents |

2022-23 Planned full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection of Privacy Rights | 123 | 142 | 159 | 158 | 158 | 153 |

| Subtotal | 123 | 142 | 159 | 158 | 158 | 153 |

| Internal Services | 50 | 51 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 |

| Total | 173 | 193 | 213 | 212 | 212 | 207 |

The increase in full-time equivalents (FTEs) in 2020-21 and future years is mainly due to resources received from the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians.

The variance between the actual FTEs in 2019-20 and planned FTEs in the coming years can be attributed to temporary funding in Budget 2019 to reduce the backlog of privacy complaints older than a year and to more quickly resolve Canadians’ complaints. The OPC will continue to achieve results by allocating its human resources to best support its priorities and programs.

The OPC took measures to ensure staffing processes were launched as quickly as possible following the funding approval. We used accelerated staffing strategies and leveraged from existing pools when possible. By the end of the third quarter of fiscal year 2020-21, the OPC had increased its staff to expected levels and is in a good position to meet its targets for future years.

Expenditures by vote

For information on the OPC’s organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2020-21.

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of the OPC’s spending with the Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available in the GC InfoBase.

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The OPC’s financial statements (audited) for the year ended March 31, 2021, are available on its website.

Financial statement highlights

Condensed Statement of Operations (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2021 (dollars)

| Financial information | 2020-21 Planned results |

2020-21 Actual results |

2019-20 Actual results |

Difference (2020-21 Actual results minus 2020-21 Planned results) |

Difference (2020-21 Actual results minus 2019-20 Actual results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 34,020,947 | 36,824,008 | 32,595,096 | 2,803,061 | 4,228,912 |

| Total revenues | 200,000 | 226,633 | 193,662 | 26,633 | 32,971 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers |

33,820,947 | 36,597,375 | 32,401,434 | 2,776,428 | 4,195,941 |

In 2020-21, actual spending increased from that of 2019-20, mainly owing to the new funding allocated for the delivery of the Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the Privacy of Canadians. This increase is primarily the result of new hires and the infrastructure required to support them in order to meet the objectives of the budget measure.

The OPC provides internal support services to other small government departments related to the provision of IT service. Pursuant to section 29.2 of the Financial Administration Act, internal support service agreements are recorded as revenues. In 2020-21, the actual revenues were higher than the 2019-20 actual revenues due to increased services provided to current clients.

Condensed Statement of Financial Position (unaudited) as of March 31, 2021 (dollars)

| Financial information | 2020-21 | 2019-20 | Difference (2020-21 minus 2019-20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 5,349,000 | 5,655,324 | (306,324) |

| Total net financial assets | 3,092,908 | 3,806,741 | (713,833) |

| Departmental net debt | 2,256,092 | 1,848,583 | 407,509 |

| Total non-financial assets | 1,720,353 | 2,182,293 | (461,940) |

| Departmental net financial position | (535,739) | 333,710 | (869,449) |

Despite a significant increase in liabilities for vacation pay and compensation time, the total liabilities decreased by $0.3 million. That decrease is mainly explained by a reduction in year-end accounts payable due to prompt payment of invoices.

The decrease in net financial assets of $0.7 million is mainly due to a decrease in the Due from the Consolidated Revenue Fund. The total non-financial assets of $1.7 million consists primarily of tangible capital assets. The $0.5 million decrease is mainly attributable to the annual amortization expense.

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Appropriate MinisterFootnote 2: David Lametti

Institutional Head: Daniel Therrien

Ministerial portfolioFootnote 3: Department of Justice Canada

Enabling Instrument(s): Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21; Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C. 2000, c. 5

Year of Incorporation / Commencement: 1982

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

“Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do” is available on the OPC’s website.

Operating context

Information on the operating context is available on the OPC’s website.

Reporting framework

The OPC’s Departmental Results Framework and Program Inventory of record for 2020-21 are shown below.

Departmental Results Framework

Core Responsibility: Protection of Privacy Rights

Departmental Result: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel that businesses respect their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel that the federal government respects their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards

- Indicator: Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations

Departmental Result: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful

Departmental Result: Parliamentarians, and federal- and private-sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted

- Indicator: Percentage of private sector organizations that have a good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities

- Indicator: Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance

Program Inventory

- Compliance Program

- Promotion Program

Internal Services

Supporting information on the program inventory

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s program inventory is available in GC InfoBase.

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the OPC’s website.

- Reporting on Green Procurement

- Details on transfer payment programs

- Gender-based analysis plus

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures. This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs as well as evaluations and GBA Plus of tax expenditures.

Organizational contact information

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

Canada

Telephone: 819-994-5444

Toll Free: 1-800-282-1376

Fax: 819-994-5424

TTY: 819-994-6591

Website: www.priv.gc.ca

Appendix: definitions

- appropriation (crédit)

- Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

- budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

- Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

- core responsibility (responsabilité essentielle)

- An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a core responsibility are reflected in one or more related departmental results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

- Departmental Plan (plan ministériel)

- A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a 3-year period. Departmental Plans are usually tabled in Parliament each spring.

- departmental priority (priorité)

- A plan or project that a department has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired departmental results.

- departmental result (résultat ministériel)

- A consequence or outcome that a department seeks to achieve. A departmental result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

- departmental result indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

- A quantitative measure of progress on a departmental result.

- departmental results framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

- A framework that connects the department’s core responsibilities to its departmental results and departmental result indicators.

- Departmental Results Report (rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

- A report on a department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

- experimentation (expérimentation)

- The conducting of activities that seek to first explore, then test and compare the effects and impacts of policies and interventions in order to inform evidence-based decision-making, and improve outcomes for Canadians, by learning what works, for whom and in what circumstances. Experimentation is related to, but distinct from innovation (the trying of new things), because it involves a rigorous comparison of results. For example, using a new website to communicate with Canadians can be an innovation; systematically testing the new website against existing outreach tools or an old website to see which one leads to more engagement, is experimentation.

- full-time equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

- A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person-year charge against a departmental budget. For a particular position, the full-time equivalent figure is the ratio of number of hours the person actually works divided by the standard number of hours set out in the person’s collective agreement.

- gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS+])

- An analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and gender-diverse people experience policies, programs and services based on multiple factors including race ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.

- government-wide priorities (priorités pangouvernementales)

- For the purpose of the 2020-21 Departmental Results Report, those high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the 2019 Speech from the Throne, namely: Fighting climate change; Strengthening the Middle Class; Walking the road of reconciliation; Keeping Canadians safe and healthy; and Positioning Canada for success in an uncertain world.

- horizontal initiative (initiative horizontale)

- An initiative where two or more federal organizations are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

- non-budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

- Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

- performance (rendement)

- What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

- performance indicator (indicateur de rendement)

- A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

- performance reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement)

- The process of communicating evidence-based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

- plan (plan)

- The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally, a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead to the expected result.

- planned spending (dépenses prévues)

- For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts presented in Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports. - program (programme)

- Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

- program inventory (répertoire des programmes)

- Identifies all the department’s programs and describes how resources are organized to contribute to the department’s core responsibilities and results.

- result (résultat)

- A consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

- statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives)

- Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

- target (cible)

- A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

- voted expenditures (dépenses votées)

- Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an appropriation act. The vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.

Alternate versions

- PDF (1018 KB) Not tested for accessibility

- Date modified: