2018-19 Departmental Results Report (DRR)

This page has been archived on the Web

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

(Original signed by)

The Honourable David Lametti, P.C., Q.C., M.P.

Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by

the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, 2019

Catalogue No. IP51-7E-PDF

ISSN 2560-9777

Message from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

I am pleased to present the Departmental Results Report of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2019.

This marks the first time we are reporting on our results achieved against our new Departmental Results Framework (DRF), unveiled in April 2018. The DRF details what our organization does, what results we are trying to achieve for Canadians, and how we assess progress and measure success.

It is important to note that we have set the bar high. Our objectives are deliberately ambitious. While we may not achieve them all immediately, we felt we must be bold in our aspirations given the interests at stake for individual Canadians.

That being said, we have exceeded our own expectations in some areas and I am proud of our overall progress to date.

In the last federal budget, we learned that our office would receive a permanent funding increase of more than 15 per cent as well as some additional temporary funding. This is clearly a step in the right direction that will help us deliver on our existing mandate in the face of exponential growth in the digital economy. The temporary funding will help us deal with a backlog of more than 300 complaints older than a year which we expect to eliminate by 2021.

Since mandatory breach reporting came into effect under PIPEDA, the volume of reports has increased more than five-fold. New resources will enable us to more thoroughly review breach reports in both the public and private sectors.

The funding will also help increase our capacity to inform Canadians of privacy issues, their rights and how to exercise them. As well, we will be better positioned to guide organizations on how to meet their privacy obligations.

Of course, appropriate resources are just part of the solution. An effective legislative framework is even more crucial. What we need are rights-based privacy laws that confer enforceable rights to individuals, while allowing for responsible innovation. Our laws must be technology-neutral, principles-based and interoperable with those of our global partners.

Trust in the digital economy – in how both government institutions and businesses handle the personal information of Canadians – is waning. Modern legislation is key to rebuilding that trust.

In recent months, Canadian Parliamentary committees and members of Parliament from all parties have supported my office’s calls to update our laws. In May, the government responded with a white paper leading to the modernization of our data protection laws, unveiling a Digital Charter meant to protect privacy, counter misuse of data and ensure companies are communicating clearly with users.

I believe we have finally reached the point in Canada where the question of whether privacy legislation should be amended is behind us. The question before us now is how.

The right to privacy is a fundamental human right and a necessary precondition for the exercise of other rights, including freedom, equality and democracy. We cannot have a democratic public life without a private life free from systematic and systemic corporate and state surveillance.

We will continue to make optimal use of the resources given to us to carry out our mandate to uphold the privacy rights of Canadians. The new funding is an important interim measure and positive step towards achieving our targets. That being said, we continue to await much-needed legislative modernization to ensure Canadians are able to participate in the digital economy and receive government services confident that their rights will be respected.

(Original signed by)

Daniel Therrien,

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

Results at a glance

In working towards the results below, in 2018-19, the OPC’s total actual spending was $25,287,074 and its total actual full-time equivalents (FTEs) was 173.

Actual spending

$25,287,074

173

Progress on performance indicators, as of March 31, 2019.

Targets met or exceeded

Our office met or exceeded its targets related to the implementation of our formal recommendations by departments and organizations, as well as the usefulness of our information and advice to both Canadians and federal and private sector organizations.

We made some modest progress in areas where our targets are set for 2021, namely, the development of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their obligations, and information for Canadians on how to exercise their rights. We continue to work toward these targets.

Targets Missed

3 of our targets were not fully met. These targets relate to the level of awareness of privacy rights of Canadians, adoption of our recommendations by Parliamentarians, and responding to Canadians’ complaints in a timely manner. Our office recognizes that these targets are ambitious, but we will nonetheless continue to work towards achieving them in the coming year.

For more information on the OPC’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section in this report.

Results: what we achieved

This section describes, for each core responsibility, the results that the OPC achieved in 2018-19 and how OPC performed against the targets it set in its Departmental Plan for that year.

Core Responsibilities

Protection of Privacy Rights

Description

Ensure the protection of privacy rights of Canadians; enforce privacy obligations by federal government institutions and private-sector organizations; provide advice to Parliament on potential privacy implications of proposed legislation and government programs; promote awareness and understanding of rights and obligations under federal privacy legislation.

Results

Results achieved by the OPC under each of the Office’s Departmental Results are described below.

Departmental Result 1: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

Our ultimate goal is to ensure a high proportion of Canadians feel their privacy rights are respected. This year our survey of Canadians included questions related to whether they feel that businesses and government institutions respect their privacy rights. The survey results indicate that 38% of Canadians feel that businesses respect their privacy rights, while 55% feel that the federal government respects their privacy rights. Combined, an average of 46,5% of Canadians agree that government and businesses respect their privacy.

2018-19 was the first year in which our Office measured the percentage of recommendations implemented by institutions and organizations in a compliance context. Previously, our performance indicator had a similar objective but was slightly different: we measured the percentage of complaints resolved to our satisfaction. Our result against this indicator exceeded our target of 85%, at 96%. Results against the previous indicator were similarly high, with 97% of complaints and incidents (breach notifications and OPC interventions) resolved to our satisfaction. However, while these figures demonstrate that we are able to resolve instances of non-compliance after the fact on a case-by-case basis, this represents suboptimal outcomes at the expense of often lengthy investigative processes. The same issues are arising in complaints repeatedly – demonstrating that underlying issues remain. Further, this result only reflects instances that were brought to our attention by way of complaints in the first place.

We are concerned that despite positive results under these measures, only a minority of Canadians feel that commercial organizations respect their privacy rights. Clearly, high compliance with the recommendations the OPC makes at the conclusion of a limited number of investigations does not translate in trust by Canadians that organizations actually comply with the law. Changes to the legislationwould likely increase ongoing compliance with the law and thereby consumer trust.

Unfortunately, we continue to struggle to meet our service standards for investigations. We have closed approximately 50% of our complaints within service standards in the last three years, below our target of 75%, due largely to an imbalance between number of complaints and our capacity to investigate. New resources will help significantly. However, we have made important process improvements in the areas of complaint triage and early complaint resolution following the creation of the new Compliance, Intake, and Resolution Directorate (CIRD), which will allow us to address more complaints earlier in the process. As a result, we reduced the overall backlog of complaints older than 12 months by 8% from last year (354 at the end of 2017-18 to 324 at the end of 2018-19), and we expect to eliminate the backlog by 2021 as a result of the additional funds announced in Budget 2019. An external review of compliance processes and technological tools is also anticipated to result in further streamlining and automation, helping us improve the timeliness of our investigations.

Departmental Result 2: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

A key first step to empowering Canadians to exercise their privacy rights is awareness. Results from our most recent poll of Canadians show that the level of awareness of privacy rights is not yet at the level our office would like to see. Roughly two-thirds of Canadians rated their knowledge of privacy rights as good (50%) or very good (14%). Compared to our previous survey of Canadians in 2016, we note that self-declared knowledge of privacy rights remained virtually unchanged. Our goal of reaching 70% is, in our view, modest when assessed in the context of the necessity, in today’s digital world, for individuals to understand the privacy implications of the technologies they rely on to go about their daily lives. We hope that the awareness effort we do through communications and outreach activities to the general public, new or updated information and guidance, as well as some enhancements to our website, which are admittedly modest given our resources, will help nudge us closer to that target.

In 2018-19, we asked Canadians for the first time to rate their knowledge of how to protect their privacy rights. Just over half-rated it as good or very good. We note that the number of Canadians who feel confident they have enough information on how new technologies might affect their privacy dropped between 2016 and 2018, going from 52% to 48%. These findings indicate that further work needs to be done to make an impact on the privacy awareness of Canadians.

In this last year, we produced guidance on a number of topics to inform Canadians on how to exercise their rights, and to guide organizations on how to meet their privacy obligations. To date we have completed five pieces of guidance from our planned list, including during the past year, our Guidelines for Obtaining Meaningful Consent, Guidance on inappropriate data practices: Interpretation and application of subsection 5(3), updated our guidance document Your privacy at airports and borders and What you need to know about mandatory reporting of breaches of security safeguards. All in all, we have issued guidance on 17% of our planned list of 30 key privacy issues for which no guidance currently exists, and we continue to work towards our target of 90% by 2021. We have received limited new funding in Budget 2019 to address this gap but, given the exponential pace of technological change, the need to keep up and produce relevant and timely guidance will continue to exceed even our enhanced resources.

While our guidance plan is developed with a view toward key issues of relevance and currency, as part of our ongoing environmental scanning and external engagement, we keep abreast of new and emerging issues. Two such matters – the legalization of cannabis and the privacy practices of political parties – came to our attention and were significant enough to warrant their own guidance pieces, above and beyond our planned list.

As the OPC website is the primary communications channel between the organization and Canadians, we aim to provide useful information on our website. This year marked our first year of formally measuring level of Canadians’ satisfaction with the information we provide. Overall, 72% of Canadians find the information on our website useful. The quantitative feedback we have received from users allowed us to select and prioritize the topics to work on and the specific content to update. The qualitative feedback allowed us to tailor the content to the needs of Canadians.

Departmental Result 3: Parliamentarians, and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

In recent years, we have experienced a steady increase in Parliamentary requests for input on bills and studies. In 2018-19 alone, the OPC engaged with Parliament thirty (30) times on various Bills, Studies and issues. We are encouraged that our appearances and statements help to deepen the understanding of privacy, and further the conversation on how best to protect the privacy rights of Canadians, particularly in the context of the adoption of laws that may have an impact on privacy.

In 2018-19, our office started to track the take-up of our recommendations to Parliament. This is a key area of potential impact for privacy protection, and we note that 35% of our recommendations were adopted by Parliament. This includes important bills such as the government’s entry-exist legislation (Bill C-21), where our recommendations on the retention period for information to be collected under the entry-exit program were adopted.

Our Office also piloted a small number of advisory activities to build and refine our business advisory services. These activities are meant to engage businesses proactively to help guide them so that they can meet their privacy obligations. In all, our Office conducted 21 advisory engagements with a number of small and medium enterprises. However, a few involved large and significant projects and initiatives, such as the Smart Cities Challenge launched by Infrastructure Canada; and the Quayside Project being developed by Sidewalk Toronto whose work is still ongoing at this time. Overall, the businesses that consulted our Office came from a broad range of industries such as automotive, infrastructure, technology, finance, real estate, retail, etc. We are pleased to note that the initial uptake of advice was strong.

Besides the guidance work described earlier in this section of the report, we have also worked to implement our multi-year communications and outreach strategy to increase businesses’ awareness of privacy obligations. For example, we published web content and printed publications on consent and on mandatory reporting of breaches, including, but not limited to, guidance, promo cards, and an infographic. The material aimed specifically at organizations, such as guidance documents, interpretation bulletins and case summaries generated around one million visits on our website in 2018-19. We also produced a bilingual insert into a CRA mail-out which was sent to over 200,000 small businesses across Canada. We exhibited at 12 events targeting businesses with a total potential reach of 13,250 visitors. We also spoke at 14 speaking engagements which reached an estimate 1,320 people. We plan to conduct a survey of businesses to measure their awareness and understanding of their privacy obligations in the coming year.

On the public sector side, our Office shifted its focus toward early, informal and as-needed interactions with government institutions. Our goal is to provide timely advice that has an impact and improves privacy for Canadians and helps encourage a Privacy by Design approach to government services. The response to our proactive approach has been notably positive. We have seen a doubling of requests from the previous fiscal year, with 46 consultations occurring in 2018-19. In addition, we have more than doubled our outreach work.

Overall, our Office strives to produce advice and guidance for federal and private sector organizations that is useful in helping them comply with their privacy obligations. This year was the first year that we formally measured organization’s satisfaction level with the guidance provided by our Office. Overall, 73% of federal and private sector organizations found the guidance on our website useful.

Finally, we were pleased to learn that additional resources have been set aside for our Office as part of Budget 2019. These funds will help us increase our capacity to engage meaningfully with Canadians and businesses, address privacy issues as they arise and; will help our office get closer to our ambitious goals and our targets in future years.

Summary Results Table

The summary table below provides an overview of the results achieved against our targets set in the first year of implementation of our new Departmental Results Framework. This Framework, which took effect on April 1, 2018, includes a number of new indicators for which results for years prior to 2018-19 are not available. In those instances, actual results have been marked as “n/a”.

| Departmental Results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2018-19 Actual results |

2017-18 Actual results |

2016-17 Actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met. | Percentage of Canadians who feel their rights are respected. | N/A | Baseline year | 46.5%Footnote 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards. | 75% | March 31, 2019 | 50% | 54% | 55% | |

| Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations. | 85% | March 31, 2019 | 96% | N/A | N/A | |

| Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights | Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights. | 70% | March 31, 2019 | 64% | Not a survey year | 65% |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | N/A | N/A | |

| Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful. | 70% | March 31, 2019 | 72% | N/A | N/A | |

| Parliamentarians, and public and private sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights | Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted. | 60% | March 31, 2019 | 35% (33 recs made, 11 adopted) | N/A | N/A |

| Percentage of private sector organizations that have good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations. | 85% | March 31, 2020 | Not a survey year | 82% | Not a survey year | |

| Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities. | 90% | March 31, 2021 | 17% (5/30 specified pieces of guidance done) | N/A | N/A | |

| Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance. | 70% | March 31, 2019 | 73% | N/A | N/A |

| 2018-19 Main estimates |

2018-19 Planned spending |

2018-19 Total authorities available for use |

2018-19 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2018-19 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18,160,148 | 18,160,148 | 19,105,857 | 18,504,642 | 344,494 |

| 2018-19 Planned full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Actual full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 133 | 123 | (10) |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s Program Inventory is available in the GC InfoBase.

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are:

- Acquisition Management Services

- Communications Services

- Financial Management Services

- Human Resources Management Services

- Information Management Services

- Information Technology Services

- Legal Services

- Materiel Management Services

- Management and Oversight Services

- Real Property Management Services

At the OPC the communications services are an integral part of our education and outreach mandate. As such, these services are included in the Promotion Program. Similarly, the OPC’s legal services are an integral part of the delivery of compliance activities and are therefore included in the Compliance Program.

Results

The OPC’s internal services functions continued to deliver high-quality and timely advice and services across the organization, in support of organizational goals.

In 2018-19, these functions also played a vital role in support of several major change initiatives including:

- finalizing the organizational review and transitioning towards a new organizational structure including the redesign of the Compliance sector;

- adopting a new Department Results Framework and performance measurement and planning frameworks;

- implementing Information Management and Information Technology (IT) strategies;

- implementing various Central Agencies initiatives and requirements, and

- working towards obtaining additional funding for the Office.

Many of these important initiatives will carry into 2019-20.

| 2018-19 Main estimates* |

2018-19 Planned spending* |

2018-19 Total authorities available for use |

2018-19 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2018-19 Difference (actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,824,997 | 6,824,997 | 7,174,551 | 6,782,432 | (42,565) |

| * Includes Vote Netted Revenue authority (VNR) of $200,000 for internal support services to other government organizations. | ||||

| 2018-19 Planned full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Actual full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Difference (actual full-time equivalents minus planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 48 | 50 | 2 |

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

Actual expenditures

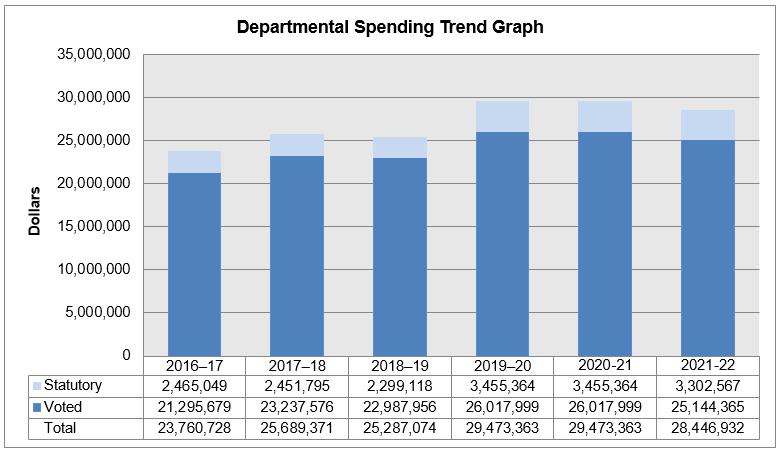

Text version

Departmental Spending Trend Graph

| Fiscal year | Total | Voted | Statutory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–17 | 23,760,728 | 21,295,679 | 2,465,049 |

| 2017–18 | 25,689,371 | 23,237,576 | 2,451,795 |

| 2018–19 | 25,287,074 | 22,987,956 | 2,299,118 |

| 2019–20 | 29,473,363 | 26,017,999 | 3,455,364 |

| 2020-21 | 29,473,363 | 26,017,999 | 3,455,364 |

| 2021–22 | 28,446,932 | 25,144,365 | 3,302,567 |

The graph above illustrates the OPC’s spending trend over a six-year period from 2016-17 to 2021-22. Fiscal years 2016-17 to 2018-19 reflect the organization’s actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts. Fiscal years 2019-20 to 2021-22 represent planned spending.

The overall spending trend in the graph illustrates an increase from 2016-17 to 2018-19. The OPC’s spending in 2018-19 increased by $1.5M since 2016-17, primarily explained by increased spending on personnel due to the new collective agreements, including retroactive salary payments.

In fiscal year 2019-20 and 2020-21, overall OPC spending is expected to increase to $29.5M as a result of the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure: Protecting the privacy of Canadians to enhance the Office’s capacity, including its ability to engage with Canadian individuals and businesses, address complaints and respond to privacy issues as they occur.

Starting fiscal year 2021-22, OPC’s planned spending will decrease by $1.0M due to the sunset funding received in 2019-20 and 2020-21 to reduce the backlog of privacy complaints older than one year, and give Canadians more timely resolution of their complaints.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2018-19 Main Estimates |

2018-19 Planned spending |

2019-20 Planned spending |

2020-21 Planned spending |

2018-19 Total authorities available for use |

2018-19 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017-18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2016-17 Actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Compliance | * | * | * | * | * | * | 12,112,252 | 11,216,142 |

| 1.2 Research and policy development | * | * | * | * | * | * | 3,797,155 | 3,365,828 |

| 1.3 Public outreach | * | * | * | * | * | * | 2,770,740 | 2,679,125 |

| Protection of privacy rights | 18,160,148 | 18,160,148 | 21,515,555 | 21,515,555 | 19,105,857 | 18,504,642 | * | * |

| Subtotal | 18,160,148 | 18,160,148 | 21,515,555 | 21,515,555 | 19,105,857 | 18,504,642 | 18,680,147 | 17,261,095 |

| Internal Services | 6,824,997 | 6,824,997 | 7,957,808 | 7,957,808 | 7,174,551 | 6,782,432 | 7,009,224 | 6,499,633 |

| Total | 24,985,145 | 24,985,145 | 29,473,363 | 29,473,363 | 26,280,408 | 25,287,074 | 25,689,371 | 23,760,728 |

| In 2018–19, the OPC started reporting under its core responsibilities reflected in the Departmental Results Framework. | ||||||||

For fiscal years 2016-17 to 2018-19, actual spending represents the actual expenditures as reported in the Public Accounts of Canada. Fiscal years 2019-20 to 2020-21 represent planned spending.

The increase of $1.3M between the 2018-19 total authorities available for use ($26.3M) and the 2018-19 planned spending ($25.0M) is due to funding received as part of the operating carry-forward exercise, compensation related to the new collective bargainings and adjustments to the employee benefit plans.

Total authorities available for use in 2018-19 ($26.3M) compared to actual spending ($25.3M) resulted in a lapse of $1.0M. This amount represents normal operating lapses reported in the Public Accounts of Canada by the OPC.

Actual human resources

| Core Responsibility and Internal Services | 2016-17 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017-18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Planned full-time equivalents |

2018-19 Actual full-time equivalents |

2019-20 Planned full-time equivalents |

2020-21 Planned full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection of Privacy Rights | 124 | 123 | 133 | 123 | 159 | 159 |

| Subtotal | 124 | 123 | 133 | 123 | 159 | 159 |

| Internal Services | 51 | 50 | 48 | 50 | 54 | 54 |

| Total | 175 | 173 | 181 | 173 | 213 | 213 |

| * In 2018–19, the OPC started reporting under its core responsibilities reflected in the Departmental Results Framework. | ||||||

The increase in planned full-time equivalent in 2019-20 and 2020-21 compared to the planned full-time equivalent in 2018-19 includes resources received from the funding for delivering Budget 2019 measure.

Expenditures by vote

For information on the OPC’s organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2018–2019.

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of the OPC’s spending with the Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available in the GC InfoBase.

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The OPC’s audited financial statements for the year ended March 31, 2019, are available on its website.

Financial statements highlights

The financial highlights presented below are drawn from the OPC’s financial statements which are prepared on an accrual accounting basis while the planned and actual spending amounts presented elsewhere in this report are prepared on an expenditure basis. As such, amounts differ.

| Financial information | 2018–19 Planned results |

2018–19 Actual results |

2017–18 Actual results |

Difference (2018–19 Actual results minus 2018–19 Planned results) |

Difference (2018–19 Actual results minus 2017–18 Actual results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 28,598,088 | 28,615,898 | 28,972,767 | 17,810 | (356,869) |

| Total revenues | (200,000) | (173,665) | (150,409) | 26,335 | (23,256) |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | 28,398,088 | 28,442,233 | 28,822,358 | 44,145 | (380,125) |

In 2018-19, actual expenses were lower than the 2017-18 actual expenses primarily due to salary expenses from the retroactive salary payments following the signing of collective agreements.

The OPC provides Internal Support Services to other small government departments related to the provision of information technology services. Pursuant to section 29.2 of the Financial Administration Act, Internal Support Services agreements are recorded as revenues. The increase in revenues is due to increased services provided to current clients.

| Financial information | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | Difference (2018–19 Actual results minus 2017-18) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 5,886,223 | 5,862,409 | 23,814 |

| Total net financial assets | 4,327,911 | 4,333,025 | (5,114) |

| Departmental net debt | 1,558,312 | 1,529,384 | 28,928 |

| Total net financial assets | 2,468,377 | 2,700,949 | (232,572) |

| Departmental net financial position | 910,065 | 1,171,565 | (261,500) |

The decrease in net financial position ($262K) and net financial assets ($233K) is mostly explained by expenditures in 2017-18 for the renewal of its Information Technology infrastructure and equipment.

Supplementary information

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Appropriate MinisterFootnote 2: David Lametti

Institutional Head: Daniel Therrien

Ministerial portfolioFootnote 3: Department of Justice Canada

Enabling Instrument(s): Privacy Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. P-21; Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, S.C. 2000, c.5

Year of Incorporation / Commencement: 1982

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

“Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do” is available on the OPC’s website.

Operating context and key risks

Information on operating context and key risks is available on the OPC’s website.

Reporting Framework

The OPC’s Departmental Results Framework and Program Inventory of record for 2018-19 are shown below.

Core Responsibility: Protection of Privacy Rights

Departmental Result: Privacy rights are respected and obligations are met

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel their privacy rights are respected

- Indicator: Percentage of complaints responded to within service standards

- Indicator: Percentage of formal OPC recommendations implemented by departments and organizations

Departmental Result: Canadians are empowered to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who feel they know about their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of information to Canadians on how to exercise their privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of Canadians who read OPC information and find it useful

Departmental Result: Parliamentarians, and federal- and private-sector organizations are informed and guided to protect Canadians’ privacy rights

- Indicator: Percentage of OPC recommendations on privacy-relevant bills and studies that have been adopted

- Indicator: Percentage of private sector organizations that have a good or excellent knowledge of their privacy obligations

- Indicator: Percentage of key privacy issues that are the subject of guidance to organizations on how to comply with their privacy responsibilities

- Indicator: Percentage of federal and private sector organizations that find OPC’s advice and guidance to be useful in reaching compliance

Program Inventory

- Compliance Program

- Promotion Program

Internal Services

To fulfill our core responsibility, our work now falls into one of two program areas – Compliance or Promotion. Activities related to addressing existing compliance issues fall under the Compliance Program, while activities aimed at bringing departments and organizations towards compliance with the law fall under the Promotion Program.

Some activities in our previous Compliance Program were of a preventative nature. These include the review of Privacy Impact Assessments and responses to information requests from Canadians. These activities have been moved from our Compliance Program to our new consolidated Promotion Program.

| 2018-19 Core Responsibilities and Program Inventory of Record |

2017-18 Strategic Outcomes and Program Alignment Architecture |

Percentage of Program Alignment Architecture program (dollars) corresponding to new program in the Program Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| Core Responsibility: Protection of privacy rights | Strategic Outcome: The privacy rights of individuals are protected | 100% |

| Program 1.1 Compliance Program | 1.1 Compliance Activities | 77% |

| Program 1.2 Promotion Program | 1.1 Compliance Activities | 23% |

| 1.2 Research and Policy Development | 100% | |

| 1.3 Public Outreach | 100% |

Supporting information on the Program Inventory

Financial, human resources and performance information for the OPC’s Program Inventory is available in the GC InfoBase.

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the OPC’s website.

- Departmental sustainable development strategy

- Gender-based analysis plus

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures. This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs. The tax measures presented in this report are the responsibility of the Minister of Finance.

Organizational contact information

30 Victoria Street

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1H3

Canada

Telephone: 819-994-5444

Toll Free: 1-800-282-1376

Fax: 819-994-5424

TTY: 819-994-6591

Website: www.priv.gc.ca

Appendix: definitions

- appropriation (crédit) :

- Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

- budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires) :

- Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

- Core Responsibility (responsabilité essentielle) :

- An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a Core Responsibility are reflected in one or more related Departmental Results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

- Departmental Plan (Plan ministériel) :

- A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a three year period. Departmental Plans are tabled in Parliament each spring.

- Departmental Result (résultat ministériel) :

- A Departmental Result represents the change or changes that the department seeks to influence. A Departmental Result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

- Departmental Result Indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel) :

- A factor or variable that provides a valid and reliable means to measure or describe progress on a Departmental Result.

- Departmental Results Framework (cadre ministériel des résultats) :

- Consists of the department’s Core Responsibilities, Departmental Results and Departmental Result Indicators.

- Departmental Results Report (rapport sur les résultats ministériels) :

- A report on an appropriated department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

- experimentation (expérimentation) :

- Activities that seek to explore, test and compare the effects and impacts of policies, interventions and approaches, to inform evidence-based decision-making, by learning what works and what does not.

- full-time equivalent (équivalent temps plein) :

- A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person year charge against a departmental budget. Full time equivalents are calculated as a ratio of assigned hours of work to scheduled hours of work. Scheduled hours of work are set out in collective agreements.

- gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS+]) :

- An analytical process used to help identify the potential impacts of policies, Programs and services on diverse groups of women, men and gender differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability.

- government-wide priorities (priorités pangouvernementales) :

- For the purpose of the 2018–19 Departmental Results Report, those high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the 2015 Speech from the Throne, namely: Growth for the Middle Class; Open and Transparent Government; A Clean Environment and a Strong Economy; Diversity is Canada’s Strength; and Security and Opportunity.

- horizontal initiatives (initiative horizontale) :

- An initiative where two or more departments are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

- non-budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires) :

- Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

- performance (rendement) :

- What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compared to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

- performance indicator (indicateur de rendement) :

- A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

- performance reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement) :

- The process of communicating evidence based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

- plan (plan) :

- The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead up to the expected result.

- planned spending (dépenses prévues) :

- For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts presented in Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports. - priority (priorité) :

- A plan or project that an organization has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired Strategic Outcome(s) or Departmental Results.

- program (programme) :

- Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

- result (résultat) :

- An external consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

- statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives) :

- Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

- Strategic Outcome (résultat stratégique) :

- A long term and enduring benefit to Canadians that is linked to the organization’s mandate, vision and core functions.

- target (cible) :

- A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

- voted expenditures (dépenses votées) :

- Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an Appropriation Act. The Vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.

Alternate versions

- PDF (824 KB) Not tested for accessibility

- Date modified: