Evaluation of Work Under the Strategic Privacy Priorities: Consent Model & Youth Initiatives

PREPARED FOR: Office of the Privacy Commissioner

PREPARED BY: Goss Gilroy Inc.

Management Consultants

Suite 900, 150 Metcalfe Street

Ottawa, ON K2P 1P1

Tel: (613) 230-5577

Fax: (613) 235-9592

E-mail: ggi@ggi.ca

DATE: June 22, 2021

1.0 Introduction

Goss Gilroy Inc. (GGI) is pleased to present this report on the Evaluation of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s (OPC) work to advance its Strategic Privacy Priorities. The scope of the evaluation is targeted toward the activities and accomplishments related to the Consent Model and Youth Initiatives. The evaluation was conducted between August 2020 and June 2021, with the majority of data collection having been undertaken in the spring of 2021.

1.1 Context of the Evaluation

Early in its Strategic Privacy Priorities work, the OPC committed to enhancing the consent model under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) to address concerns raised by individuals and organizations. To that end, consultations were held with stakeholders across the country both in person and online, with the goal of identifying improvements to the current consent model and clarifying the roles and responsibilities of players who could implement them.

On September 21, 2017, the OPC published a Report on Consent as part of its 2016-17 Annual Report to Parliament. The report outlined recommendations to address consent challenges posed by the digital age. The OPC subsequently developed various guidance about consent under PIPEDA, including its guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent and guidance on inappropriate data practices (no-go zones).

The OPC also undertook a number of initiatives on youth privacy to help create an environment where youth can use the Internet to explore their interests and develop as persons without fear that their digital trace will lead to unfair treatment. In the last five years, the OPC has collaborated with domestic and international partners and released various educational products to support youth digital literacy and youth privacy online.

The evaluation has sought to assess the impact of this work and provide valuable insight and lessons learned. This work was undertaken to help the OPC understand and improve upon the design and delivery of these initiatives, the achievement of immediate outcomes, and how it can best conduct its work in the future. The immediate outcomes comprise:

- Individuals are more aware of how to protect their personal information in the digital economy;

- Policy, organizational/institutional practices and/or legislation are better able to protect personal information in the digital economy;

- Individuals are more aware of the need to and how to protect their and others’ reputation when using the internet;

- Organizational/institutional policy and practice and/or legislation are better able to protect reputation in the internet.

The evaluation covers the work of the OPC from June 2015 to June 2020 related to the Consent and Youth initiatives. To note, at the same time that this evaluation was underway, the Government of Canada introduced new private-sector privacy legislation, Bill C-11, the Consumer Privacy Protection Act. This parliamentary process fell outside of the scope of the evaluation.

2.0 Methodology

The evaluation began with a series of scoping interviews with representatives of the OPC. These interviews were used to obtain an understanding of the two initiatives, to validate what was to be evaluated, and to understand areas of interest or priority to be addressed by the evaluation.

Following the scoping exercise, a methodology and evaluation plan was presented to the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee, where the approach, data collection strategy, and proposed questions to be addressed by the evaluation was approved. The evaluation questions, approved to frame the overall inquiry, comprise the following:

Relevance

EQ1: To what extent have the Strategic Privacy Priorities been useful in guiding the activities of the initiatives?

EQ2: How has the work of these initiatives adapted to emerging areas of need and relevance?

Performance

EQ3: To what extent has the work of these initiatives met the needs of stakeholders they were intended to address?

EQ4: To what extent are target populations being reached and influenced?

Efficiency

EQ5: To what extent have processes and resources (time, money, people) been adequate to achieve outcomes?

EQ6: What lessons can be carried forward? What could be done differently next time?

Embedded within the evaluation approach was the application of a change management lens, using the Prosci ADKAR® model. As one of the most used models for change management across the federal government and in the private sector, it examines change along a continuum of Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement as outcomes an individual must achieve for change to be successfully realized. This change management approach is most closely examined under evaluation question number four.

The evaluation employed a mixed-methods approach with the main methods of data collection comprising the following:

Document Review: This process entailed a systematic extraction of relevant secondary data (previously collected) from identified documents to establish evidence for specific evaluation indicators. The evaluation incorporated a review of 43 documents that were supplied by OPC.

Key informant interviews: In-depth interviews were held with internal stakeholders (e.g., OPC employees) and external stakeholders identified by OPC as being knowledgeable about the work of the organization. An effort was made to solicit participation from a balanced sample of stakeholder groups, and to incorporate perspectives that were expected to be both supportive and critical of the OPC’s work. In total, 13 interviews were conducted, bringing together 17 stakeholders who provided their perspectives. These interviews were broken down as follows:

- 3 representatives of OPC;Footnote 1

- 2 provincial representatives;

- 1 international counterpart;

- 4 representatives of associations and civil society; and,

- 7 subject matter experts.

Survey of Consulted Stakeholders: A survey was administered to organizations and individuals who had participated in the OPC’s consultations on consent in recent years. Potential respondents were sent a link to the survey, followed by two reminders. The response rate for the survey was 24% (of 124 consulted organizations who received a survey link, 30 organizations completed the questionnaire). The breakdown of respondents is show in Table 1 as follows:

| Type of organization | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Academia | 10 | 33% |

| Private business | 8 | 27% |

| Professional association/organization that represents businesses |

6 | 20% |

| Consumer protection organization | 3 | 10% |

| Other (please specify) | 2 | 7% |

| Legal intermediary | 1 | 3% |

| Youth protection organization | 0 | 0% |

Survey of teachers: A survey to teachers regarding uptake and usefulness of the OPC’s youth privacy resources was made available via an open link. This link was sent in an e-blast by CoEd Communications Inc., was pushed on social media by the OPC, and was circulated by some provincial privacy organizations to their education partners. The breakdown of the grades they are teaching is shown in Table 2 as follows:

| Level | Count | % |

|---|---|---|

| Early education (prior to grade 1/primary school) | 6 | 21.4% |

| Grade 1 to 3 / 1st to 3rd year of primary school | 7 | 25.0% |

| Grade 4 to 6 / 4th to 6th year of primary school | 11 | 39.3% |

| Grade 7 and 8 / Secondary 1 and 2 | 7 | 25.0% |

| Grade 9 to 12 / Secondary 3 to 5 | 11 | 39.3% |

| I did not teach in the last five years | 4 | 14.3% |

| Total | 28 | 100.0% |

The breakdown of the Provinces/Territories they presented are shown in Table 3 as follows:

| Province | Count | Col % |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 9 | 32% |

| Yukon | 7 | 25% |

| Alberta | 5 | 18% |

| Quebec | 5 | 18% |

| British Columbia | 3 | 11% |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 7% |

| Manitoba | 1 | 4% |

2.1 Limitations

The constraints on this evaluation were significant; characterized by minimal primary data collection. Barriers to more fulsome data collection during the study included the following:

- For the survey of consulted stakeholders, restrictions were encountered in engaging directly with stakeholders, unless they had given prior consent to the OPC to be contacted. A list of agreeable stakeholders did not exist in entirety and had to be built from information and knowledge provided by OPC staff which limited the number of possible respondents identified.

- Youth and children were not involved as evaluation participants themselves. Given the indirect nature of OPC’s work in this area, it was not totally necessary for understanding contribution towards immediate outcomes. However, their absence does mean that we have assessed work targeted at changing their behaviours, without having sought their own feedback on this very work.

- The pandemic environment placed teachers in the unprecedented position of adapting to an extremely difficult situation. Teachers are already considered a difficult stakeholder group to reach, in any evaluation, since they have many demands on their time, and the pandemic had exasperated this.

- The pandemic has resulted in lower than usual response rates for surveys overall.

- The introduction of Bill C-11 meant that many stakeholders (internal and external) were extraordinarily busy and making time for the evaluation may not have been their top priority.

These limitations have meant this evaluation is not as robust as planned and the findings are weakened as a result. The relatively small numbers mean the survey feedback in particular is not statistically significant. However, it did provide helpful feedback for the evaluation and has been used within appropriate parameters. Findings should be read in this context.

The evaluation also experienced challenges remaining in scope, given that the consent work and youth activities are not discrete programs but largely intertwined with the overall work of the OPC. Given the intention of the evaluation to be forward looking and useful to future planning, we were given blessing to tackle these indirect issues if they supported the evaluation questions. Attempts to temper any scope creep throughout the reporting have been made, and recommendations are aligned to those aspects which were within the purview of our mandate.

However, the stakeholders we did interview were quite knowledgeable, even more so than typically encountered in an evaluation, which mitigated the small numbers to a degree. Furthermore, several interviewees represented members, clients, and larger constituencies; and as such, were able to provide an aggregate perspective rather than simply their own. As always, triangulation was used to ensure findings were drawn from more than one source, with particular attention to trends across stakeholder groups.

The evaluation was also able to draw heavily from two OPC public opinion surveys, namely the Survey of Canadians and the Survey of Businesses. OPC’s online feedback tool was also helpful to understand the perceived usefulness of information and guidance. Although these sources speak more generically to privacy issues overall, they contained several questions that aligned closely to that of the evaluation. As such, these secondary sources were drawn from, especially in answering questions around behaviour change.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Relevance

EQ1: To what extent have the Strategic Privacy Priorities been useful in guiding the activities of the Initiatives?

FINDING: The Strategic Privacy Priorities of ‘Economics of Personal Information’, and ‘Reputation and Privacy’ were useful in directing work that was undertaken immediately following their launch in 2015. While the priorities are still relevant on a broad scale, these priorities need to be revisited and updated to direct future work.

Visibility of the Strategic Privacy Priorities

The Strategic Privacy Priorities that most closely align to the work of the consent and youth initiatives are: ‘Economics of Personal Information’ and ‘Reputation and Privacy’. The Economics of Personal Information covers the bulk of the resulting work on consent. While youth initiatives have a cross-cutting focus, the ‘Reputation and Privacy’ priority is the most explicit tie-in to many of the activities targeted specifically to youth.

When OPC key informants were asked about how the Strategic Privacy Priorities have been used, they reported that priorities are taken into account when planning new activities, but are more directional in nature. Staff are aware of the priorities, and give them consideration when designing new initiatives, but ensuring close alignment to the Strategic Privacy Priorities is not done systematically or rigorously. According to interviewees, the priorities also seem to have had more visibility in the years immediately following their introduction in 2015, and less so more recently.

Influence of the Strategic Privacy Priorities

For the consent work, internal interviewees reported that the Strategic Privacy Priorities ushered in some major undertakings, namely consultations and the subsequent publishing of guidance on consent, reputation and national security (as documented in the OPC’s annual reports). For work with youth, it was said that when the priorities were launched, it was a recognition of nascent efforts in youth outreach, and the area was relatively new to the OPC at the time. This formalization made it easier to allocate time and resources to continue the work that was already being undertaken in this area.

The OPC has tracked its activities emanating from the Strategic Privacy Priorities, demonstrating a continued effort to endure on commitments, as per the short term (by December 2016), medium-term (by June 2018), and longer-term plans (by June 2020). The documentation also provided evidence that the Strategic Privacy Priorities were directly used in planning some activities, especially those in communication and outreach. The document “Status update - strategic privacy priorities work” provides a description of progress.

However, noticeably absent are long-term plans for most areas, in line with what internal stakeholders indicated regarding the strategic priorities not being up to date, with diminishing explicit connections of current operations and focused activities back to the priorities set in 2015.

While internal stakeholders can broadly link current operational activities (focused on law reform) back to the strategic priority areas; the strategic priority areas are not viewed as a driver of day-to-day activities suggesting the strategy needs to be revisited, updated and treated as “evergreen,” in order to best drive operational planning and action plans.

EQ2: How has the work of these Initiatives adapted to emerging areas of need and relevance?

FINDING: OPC has clearly demonstrated dedication to understanding and responding to the needs of stakeholders through work on both the consent model and youth activities. Constraints to adaptation are the complexity of issues, as well as the OPC’s limited authority and resources.

Establishment of Needs

Research undertaken by OPC demonstrates a commitment to learning about the needs of Canadians. These efforts include a large-scale telephone survey conducted on a biennial basis that ask Canadians for their views, i.e., the Survey of Canadians on Privacy-Related Issues. This public opinion research covers areas such as concerns about protection of personal privacy; trust in organizations to protect personal information; and the extent to which Canadians feel informed about how their personal information is handled. A similarly substantial effort to remain in tune with emerging areas of need would be the OPC’s Survey of Canadian Businesses on Privacy-Related Issues. Of the two OPC surveys, the latter most closely touches on the consent model work.

When asked about work stemming from the consent consultations, key informants agreed that the guidelines for meaningful consent and guidelines for inappropriate practices addressed areas of emerging need. Interviewees maintained that this work gave direction that was responsive to needs as expressed in consultations. (See more feedback on these consultations in Section 3.2).

The initial youth activities were similarly grounded in needs assessment work, and in line with the International Competency Framework on Privacy Education. An assessment of curricula nation-wide identified gaps in privacy-related education, and in particular, it was noted that there was very little for Grades 4 and under. The OPC responded to this need by working with provinces and territories to develop activity sheets and a graphic novel on how youth can protect their privacy that have been well received.

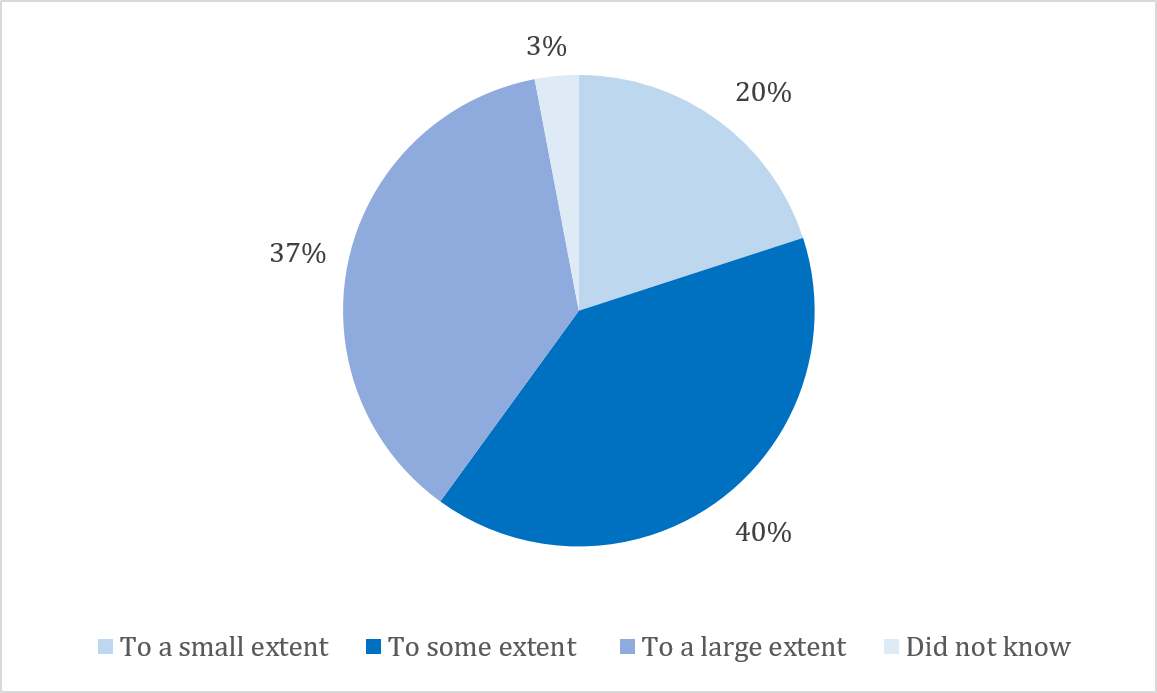

Agility and Practicality

While some key informants suggested the OPC pivots well to emerging needs, others felt they lagged behind on important and fast-moving issues. The evaluation explored these issues most deeply in the context of the consent work and youth initiatives, though the questions themselves and feedback received expand beyond; this is in keeping with the approach of using the evaluation as an opportunity for broader learning. These interviewees would like to see OPC’s guidance developed more quickly in order to keep up with challenges as they are presented. Respondents to the survey of consulted organizations gave similarly mixed reviews when asked whether the OPC is responsive to new and emerging issues in developing guidelines and guidance material on consent. 20% said the OPC is responsive ‘to a small extent’, 40% said ‘to some extent’, and 37% said ‘to a large extent’. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: OPC Responsiveness to New and Emerging Issues in Developing Guidelines

Text version of Figure 1

| Extent | Responsiveness |

|---|---|

| To a small extent | 20% |

| To some extent | 40% |

| To a large extent | 37% |

| Did not know | 3% |

Respondents who did not feel the OPC was responsive elaborated in their comments that:

- The OPC is reactive and slow to adapt to change – hence does not develop early guidance or standards or best practices;

- Guidance is not contextualized or practical for businesses; and,

- The definition of consent upheld by the OPC is too “broad” or “archaic”Footnote 2.

Key informants expressed similar concerns regarding practicality. Respondents want to see more depth and assistance in how to apply OPC’s high-level guidance to the day to day matters they wrestle with. In other words, stakeholders would like guidance that explores more challenging ‘grey areas’ as they emerge, i.e., difficult scenarios in which guidance from OPC would be helpful to understand how to operationalize privacy requirements in complex data environments. These interviewees expressed a desire to better understand how to answer more difficult questions, for example, such as whether consent is needed to anonymize data. Other examples used here related to youth, such as privacy concerns in areas such as online educational platforms and their unplanned proliferation during the virtual schooling environment.

Constraints to Responsiveness

Key informants also indicated a number of constraints to the OPC’s ability to be responsive.

Resources were identified as a challenge by both internal and external interviewees, with the acknowledgement that with greater resources, OPC might be able to address more issues more quickly. Lack of authorities was also flagged as a barrier. Some stakeholders recognized the powers of the OPC are limited and this is impacting its ability to be proactive or tackle issues more forcefully. Also, some stakeholders were left waiting for guidance resulting from investigations that took several years to be completed. Lastly, the speed and complexity of change in the domain of privacy is significant, and occur in multiple industries and sectors simultaneously.

Ongoing Needs

In the spirit of making the evaluation helpful to inform future planning, stakeholders were asked about their ongoing needs. Specific areas in which evaluation participants (interviewees and survey respondents) requested more detailed information, included the following:

- Clarity on whether and to what extent charities are subject to PIPEDA;

- Consent and anonymization;

- How the private sector can implement principles on consent and Artificial Intelligence;

- Artificial Intelligence and children/youth;

- Updated online advertising guidelines;

- Solutions to obtaining consent in dynamic data environments;

- Additional guidance related to minors;

- More advice on safeguarding and handling data;

- More information and training for teachers;

- Practical sector-specific guidance; and,

- Guidance pertaining to specific situations/scenarios/technologies.

Mandate Fulfilment

Stakeholders were asked about the extent to which the OPC’s work regarding consent and youth privacy in the last five years contributed to fulfilling its mandate of protecting and promoting the privacy rights of individuals, as well as overseeing compliance of PIPEDA and the Privacy Act. Overall, stakeholders identified that the activities undertaken on the consent model and youth initiatives were clearly aligned to the OPC’s mandate and contributed to advancements in privacy protection. Overall, the OPC is viewed as a contributor to an increase in privacy awareness among both youth and adults.

A few stakeholders suggest that the OPC could be doing more in terms of protecting and promoting the privacy rights of youth in particular. While lauding the organization’s work in supporting education of these issues, the intersection between consent and youth was viewed as somewhat weaker. One example raised was the Report on Consent containing only one paragraph pertaining to children and youth. Some had expected more formal guidance on youth specific issues to be addressed; at the same time, findings of investigation also act as de facto guidance.

At the same time, a few stakeholders highlighted the contributions of the OPC in subnational and international jurisdictions to promote the privacy rights of youth. More specifically, these interviewees highlighted the OPC’s role in the 2017 GPEN Sweep Report: Online Educational Services, as well as its leadership in Canada through facilitating relevant Federal-Provincial-Territorial working groups.

Barriers to even greater fulfilment of the mandate were cited to be the breadth of the mandate; the size of the office; its limited authorities; and that education is a provincial jurisdiction.

3.2 Performance

EQ3: To what extent has the work of these initiatives met the needs of stakeholders they were intended to address?

FINDING: OPC’s high-level guidance materials are used and considered helpful – especially the guidelines on obtaining meaningful consent. However, challenges exist in interpreting and implementing revised or emerging guidance that comes as a surprise.

The OPC Consultation Process

The scoping interviews identified the OPC’s approach to stakeholder consultations as an area of particular interest for the evaluation. The consultations on consent under PIPEDA – which began in 2016 and led to the development of the 2018 Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent – also represent an important part of the work done under this portfolio during the evaluation period. The OPC did not hold formal consultations on youth privacy. According to strategic documents, the OPC develops resources and activities based on the input of adults who are directly in contact with youth (e.g., organizations, parents, educators and community leaders). In addition to this, needs assessment work was conducted at the outset of the youth initiatives (as discussed earlier in Section 3.1).

Consultations on the Consent Model

The consultation process regarding consent under PIPEDA began with the publication of a discussion paper to which stakeholders (organizations, individuals, academic, advocacy groups, specialists, etc.) were asked to react through written submissions. The OPC received 51 submissions, about half of which were from businesses. The OPC then organized roundtables to further discuss consent with stakeholders. The OPC then summarized the input from the submissions and roundtables in its 2016-17 Report on Consent. In 2017, the OPC asked stakeholders for feedback on two draft guidance documents: the Guidelines on Obtaining Meaningful Consent and the document on inappropriate data practices. The OPC received 13 submissions.

Responses indicate that stakeholders want the OPC to continue to conduct structured consultations in the future. Key informant interviewees and survey respondents who had participated in the consent consultations (or were otherwise knowledgeable about the process) rated the OPC’s approach as good overall. Suggestions from respondents who were not very familiar with the consent consultations aligned with the OPC’s current approach. More specifically, respondents noted the following elements to be important:

- Early engagement (e.g., via a discussion paper) and advance notice;

- Giving stakeholders various channels to provide input (i.e., written submissions and roundtables); and importantly,

- Giving stakeholders the opportunity to react to draft guidance.

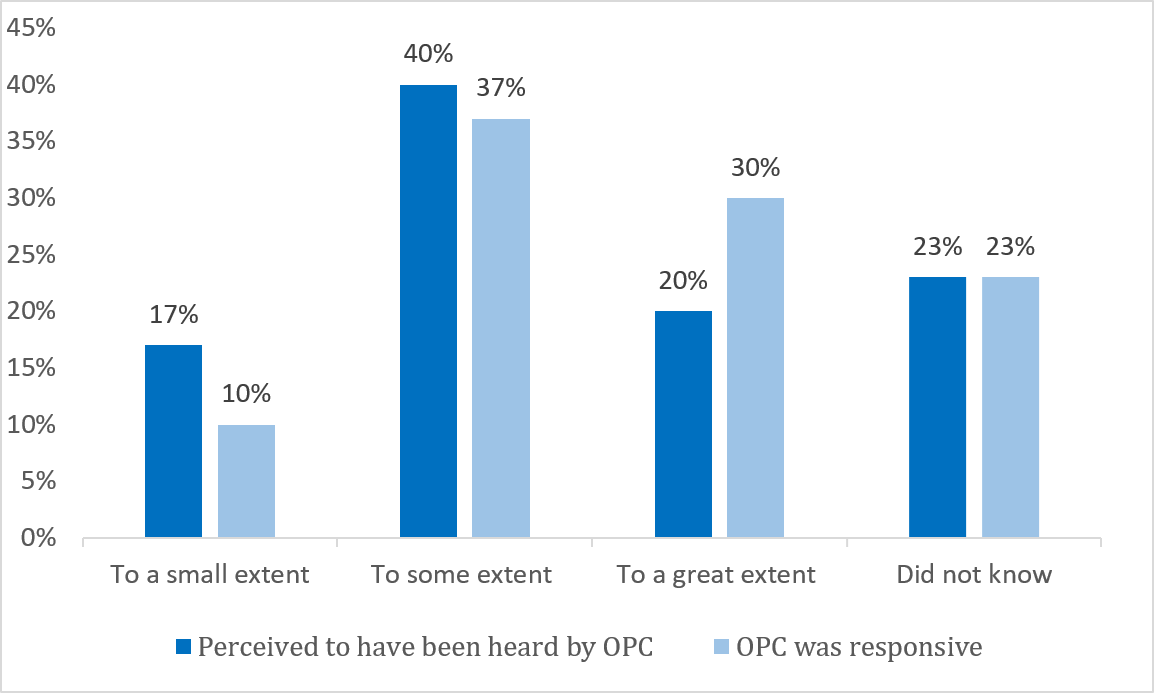

To the question of whether organizations perceived to be heard as part of the OPC's consultations on consent, survey respondents gave varied answers. Five (17%) felt they had only been heard to a small extent, 12 (40%) to some extent and 6 (20%) to a great extent and 7 respondents (23%) indicated they did not know. Views are similar on whether the OPC was responsive to the input of stakeholders in general, although a little more positive: 3 respondents said the OPC was responsive to a small extent (10%), 11 said ‘to some extent’ (37%) and 9 said ‘to a large extent’ (30%). Answers vary amongst respondents from the same stakeholder category – i.e., academia, private sector, associations, etc. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Perceived to be Heard by OPC and OPC’s Responsiveness to the Input of Stakeholders

Text version of Figure 2

| Extent | Perceived to have been heard by OPC |

OPC was responsive |

|---|---|---|

| To a small extent | 17% | 10% |

| To some extent | 40% | 37% |

| To a great extent | 20% | 30% |

| Did not know | 23% | 23% |

When asked to elaborate on the reasons why they believed the OPC was not fully responsive to the input of stakeholders, survey respondents most frequently said that the guidance did not incorporate input from businesses on the practical application of consent. Key informant interviewees also noted that the OPC’s guidance did not fully reflect critical input from businesses on how to make the guidance most useful and adapted to their context. A few interviewees explained they disagreed fundamentally with the definitions or approach the OPC had adopted in the guidance. While the evaluation did not explore the OPC’s business outreach function in particular, we did hear that stakeholders felt uncomfortable approaching it, anticipating interaction with the business outreach group could trigger a compliance investigation.

In terms of ways to improve the consultation process, most stakeholders call for a predictable, well laid-out process that gives them sufficient time to prepare and provide input. Respondents encouraged the OPC to give clear and generous timelines to allow stakeholders to prepare and allow for broader participation (e.g., communicating a consultation “roadmap” with expected timelines). Survey respondents and key informants suggested a few ways the OPC could better engage businesses, civil society organizations and other stakeholders to collect their input on issues of consent. Some repeated suggestions included the following (some of which OPC is already doing):

- Continue holding formal consultations (e.g., written and in-person via roundtables - e.g., sectoral roundtables);

- Engage stakeholders in a structured, targeted way via specific and practical questions (e.g., as opposed to a general ‘what do you think’ approach);

- Ensure the OPC engages a variety of players, i.e., not only (large) businesses, but also smaller players, associations, civil society organizations;

- Ensure the consultation process gathers representation from across Canada;

- In parallel to formal consultations, being open to informal discussions, debates, and direct exchanges with stakeholders (e.g., having an ‘open door’ approach);

- Being present at sector-specific events, conferences; and,

- Conducting surveys and research.

Mechanisms for Feedback

The evaluation process itself discovered that the OPC does not have a good mechanism to collect feedback. For instance, the OPC could only contact a consulted stakeholder directly for this evaluation if they had consented earlier to being followed-up with. Also, given the delay between the consultations and the evaluation, many individual representatives had changed organizations. Furthermore, the OPC does not have a comprehensive “stakeholder list” to draw from for communications (e.g., emails) – a list that interested parties could ask to be added to, and which would be kept up-to-date. There are some elements in place however, such as an online feedback tool and a presence on social media. However, if the OPC intends to undertake more stakeholder engagement in the future, compiling such a list of contacts would prove useful to push information out to the community, as would building in consent for feedback from the beginning.

Use and Impact of OPC Resources on Consent

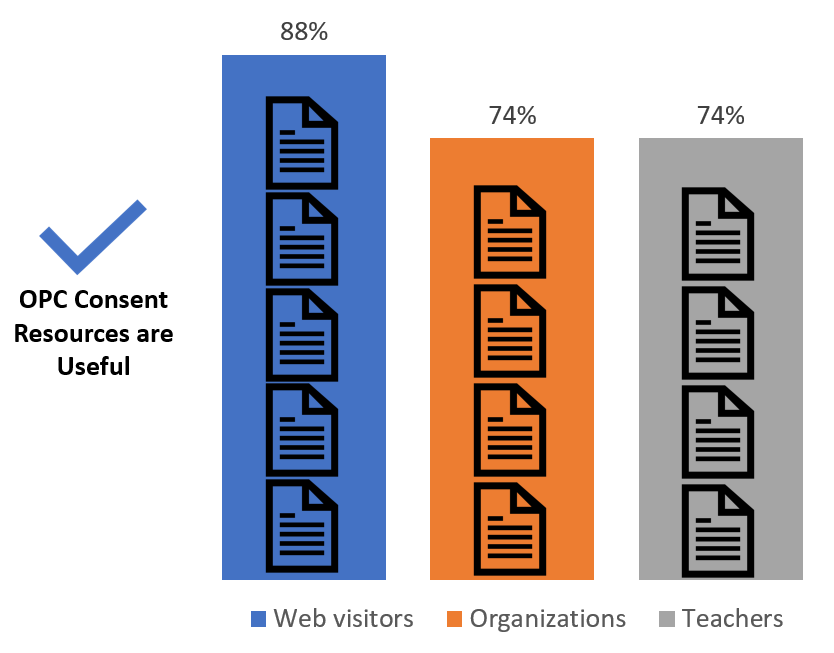

Comments from key informants and survey respondents indicate that the OPC’s high-level guidance on privacy issues (for both consent and youth initiatives) is valuable. Guidance is welcomed and considered clear overall.

Looking across the feedback from website visitors, the survey of consulted organizations, as well as the survey of teachers, the aggregate picture of the usefulness of resources is largely positive, as indicated in the below (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Usefulness of OPC’s resources

Text version of Figure 3

| Respondent | Usefulness |

|---|---|

| Web visitors | 88% |

| Organizations | 74% |

| Teachers | 74% |

All but one respondent in the consent stakeholder survey had accessed resources published by the OPC regarding consent. Most had done so multiple times (64%) and had recommended the material to others (85%). Most respondents who had accessed resources confirmed the resources were useful (48%) or somewhat useful (24%) to understand their organization's obligations related to consent under PIPEDA. The remaining 8 respondents selected “don’t know/not applicable”. The five resources on consent most frequently used by consulted stakeholders who responded to the survey were:

- Guidelines on obtaining meaningful consent;

- Findings of PIPEDA investigations,

- The OPC's discussion paper on potential enhancements;

- The OPC report on consent, and,

- General information on PIPEDA and organization’s responsibilities.

Several key informant interviews noted that the Guidance on inappropriate data practices: Interpretation and application of subsection 5(3), referred to as the ‘no-go zones’ were also very useful to them or the organizations they work with.

Amongst website visitors who consulted the Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent and used OPC’s website feedback tool, 29 of 33 respondents (88%) indicated it was useful to them. Most respondents to the survey of organizations consulted about consent confirmed they found the consent resources useful, but how useful depends on the resource. Most who had used the Guidelines also considered them useful, to a significant extent (74%) or to some extent (26%). Those proportions are 59% and 36% respectively for the findings of investigations and results are more mixed for the other popular resources. General information on PIPEDA were mostly considered of “some” use (67%), as are discussion papers (52%) and the report on consent (52%).

The most frequent criticism regarding consent material (especially the guidelines) is that OPC is not in tune with business environments and that the guidance – albeit clear – can be impractical to operationalize or not specific or specialized enough to be fully useful. Some key informants also described the impact of “surprise” guidance issued in wake of investigations when reports of investigations are published, stakeholders are sometimes left to wonder how the findings affect them and whether or not they need to change their practice as a result. This is not to suggest there should be fewer investigations; as mentioned above the findings from PIPEDA investigations are one of the resources on consent most frequently used by consulted stakeholders. One respondent suggested that reports of investigations should be published along with a short, digestible document that clarifies the conclusions and help businesses understand exactly what they need to do. We understand such work to be underway.

Final comments from the survey included the following suggestions for the OPC in terms of developing guidance on consent:

- Offer more advice on safeguarding and handling data;

- Collaborate with IT Industry Associations;

- Establish an advisory board of key stakeholders;

- Conduct more comparisons with foreign regimes like the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR);

- Modernize the concept of consent, and,

- Better inform Canadians and putting more emphasis on protecting the rights and privacy of individuals.

Use and Impact of OPC Resources on Youth Privacy

Survey results hint at the usefulness of the OPC’s youth privacy resources. Eighteen (18) of the 30 respondents (60%) to the consulted stakeholder survey indicated that their work touched on youth privacy. Of those 18, 16 had consulted OPC resources specifically regarding youth privacy or obtaining meaningful consent from youth, and 14 of the 16 confirmed the resources were useful.

Only seven surveyed teachers confirmed they had actually used OPC resources, and most indicated the resources had been useful to them to some or a significant extent and 4 of the 7 had recommended OPC materials to others. Furthermore, OPC resources were hyperlinked in the survey and between 35% and 57% of teachers indicated they could potentially (or were planning to) use the OPC’s resources (responses varied depending on the type of resource and its target demographic). For instance, at least half of all teachers indicated they could use or planned to use online resources for adults and parents, presentation packages for Grades 4 to 12, the graphic novel and the privacy quiz. When asked what resources they would need on youth privacy, teachers responded:

- More information/training for teachers;

- Content tailored for different populations (e.g., parents, early education, teenagers);

- Ready-to-deliver material that is engaging and interactive (e.g., video, games/interactive activities (story-based)); and,

- Content that youth will identify with.

EQ4: To what extent are target populations being reached and influenced?

FINDING: OPC is considered to be a credible and respected source of information on consent and youth privacy issues. It has effectively leveraged the work of organizations that have a larger presence with target populations, including funded organizations and provinces, to maximize its reach. When it comes to changing behaviour, the OPC is contributing most to raising awareness. OPC collaborates well with diverse stakeholder groups in Canada, and has taken a leadership role on the international stage.

A key part of this evaluation has been to examine the extent to which the OPC is able to influence behaviour change with respect to the consent model and youth privacy; at the same time, these aspects are also the most difficult to assess. In order to frame this inquiry, a change management approach was used to shape our questions to evaluation respondents, in an effort to gauge where along the spectrum of change target populations may fall.

Reach and Credibility

Credibility

Credibility is a critical precursor to influence. A large majority of evaluation participants view the OPC as a credible and respected source. Key informants reported that the guidance developed by the OPC is well articulated and carefully considered. We also heard that OPC does not shy away from approaching difficult issues, and is ‘in the lead’ for establishing norms and expectations.

Most teachers (61%) who responded to the survey considered themselves ‘a bit familiar’ with the OPC. Similar to key informant interviewees, most teacher survey respondents who said they knew the OPC found it either somewhat (43%) or very credible (43%).

The survey of consulted organizations demonstrated concurrence with these views. Most survey respondents (73%) consider the OPC to be a ‘very credible’ source of information regarding issues of consent under PIPEDA. The remaining 7 respondents (23%) indicated that the OPC is ‘somewhat’ credible. Respondents were asked to elaborate why they did not see the OPC as fully credible. The five respondents who provided comments (a mix of academics, practitioners and businesses) cannot be generalized, but exemplify some of the issues that might preoccupy stakeholders with regards to the OPC’s work:

- The OPC’s perspective is too narrow and does not account for all social and economic factors (from a respondent who identifies as a ‘practitioner’);

- The OPC has limited understanding of business reality (from two private business respondents);

- The OPC lacks the resources (people) and technical expertise to handle complex issues concerning consent (from a respondent from academia); and,

- The OPC does not effectively protect or defend individuals’ rights against surveillance and big data advertisement on digital platforms (from a respondent from academia).

Key informants echoed these issues, most notably the perception that the OPC has a limited understanding of the business world and insufficient technical expertise to handle complex issues concerning consent.

It was also noted that OPC’s engagement with youth is indirect. Noting that education is a provincial jurisdiction, it was felt that perhaps OPC could have a louder voice and greater visibility in the youth privacy community, where respondents identified this would provide a sense that the OPC is in tune with youth concerns and realities.

Reach

The OPC makes an effort to capture its overall reach, and indeed has continued to receive attention throughout the duration of the evaluation scope in terms of media requests and visibility online. These metrics encompass both youth and consent work, though obviously expand beyond these two initiatives as well. The below evidence should be interpreted in that context.

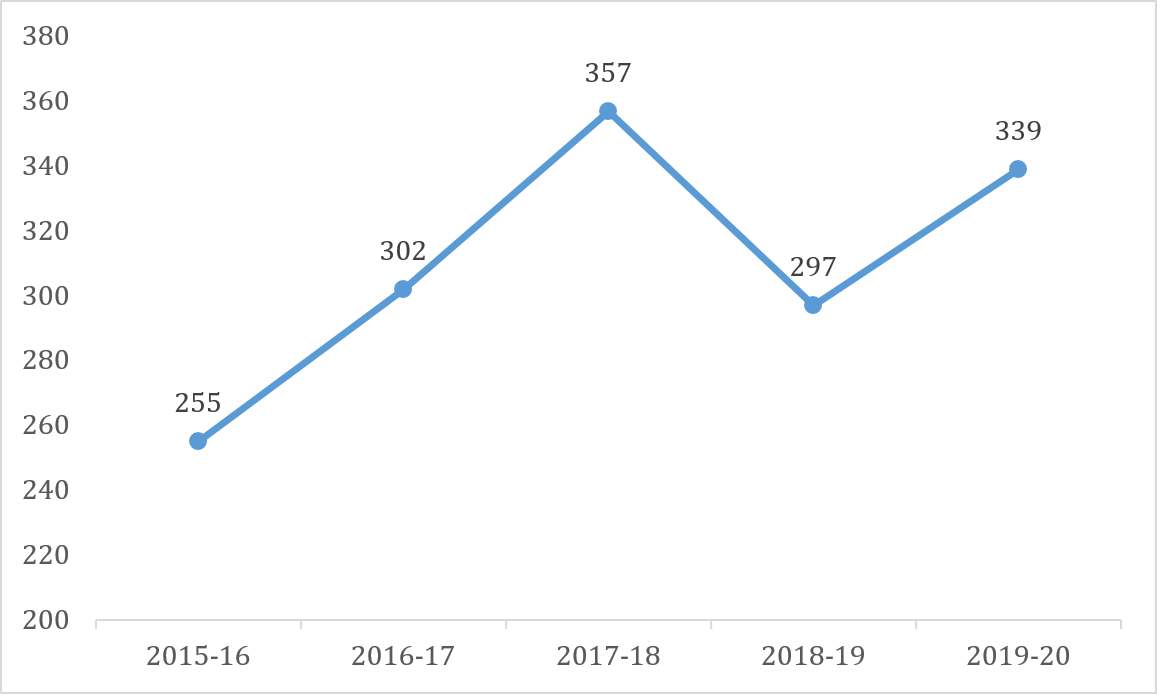

The OPC provides an inbox for journalists to make media enquiries. As shown in Figure 4 below, the OPC receives a number of media requests each year, ranging from 255 to 339 over the past few years. Whether the OPC launches major announcements and what is happening in the news (Such as a transition to a new government) greatly contribute to the fluctuating trend.

Figure 4: OPC Annual Media Requests

Text version of Figure 4

| Year | Media requests |

|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 255 |

| 2016-17 | 302 |

| 2017-18 | 357 |

| 2018-19 | 297 |

| 2019-20 | 339 |

Source: Communications Quarterly AnalysisFootnote 3

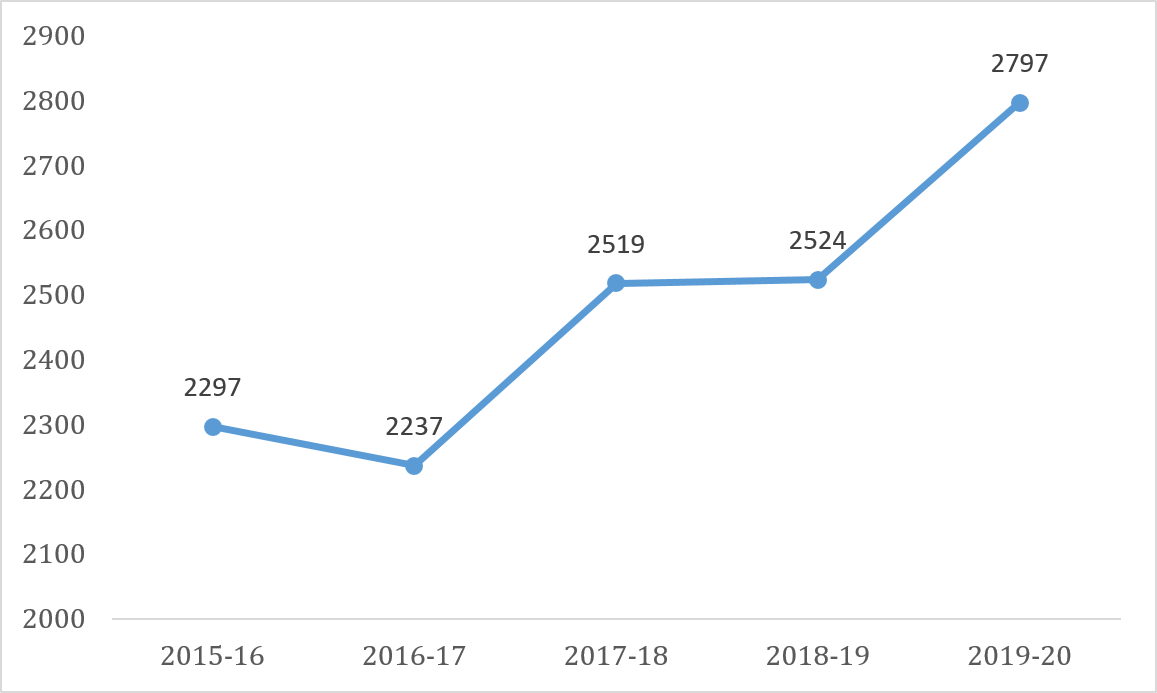

In addition, individuals and organizations can reach the OPC information centre by mail, telephone or via an online information request form. The OPC information centre responds to several thousand requests from the general public for information about privacy each quarter. As Figure 5 shows, an increasing number of individuals and organizations reach out to OPC for information.

Figure 5: OPC Average Yearly Information Enquiries

Text version of Figure 5

| Year | Enquiries |

|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2297 |

| 2016-17 | 2237 |

| 2017-18 | 2519 |

| 2018-19 | 2524 |

| 2019-20 | 2797 |

Source: Communications Quarterly Analysis

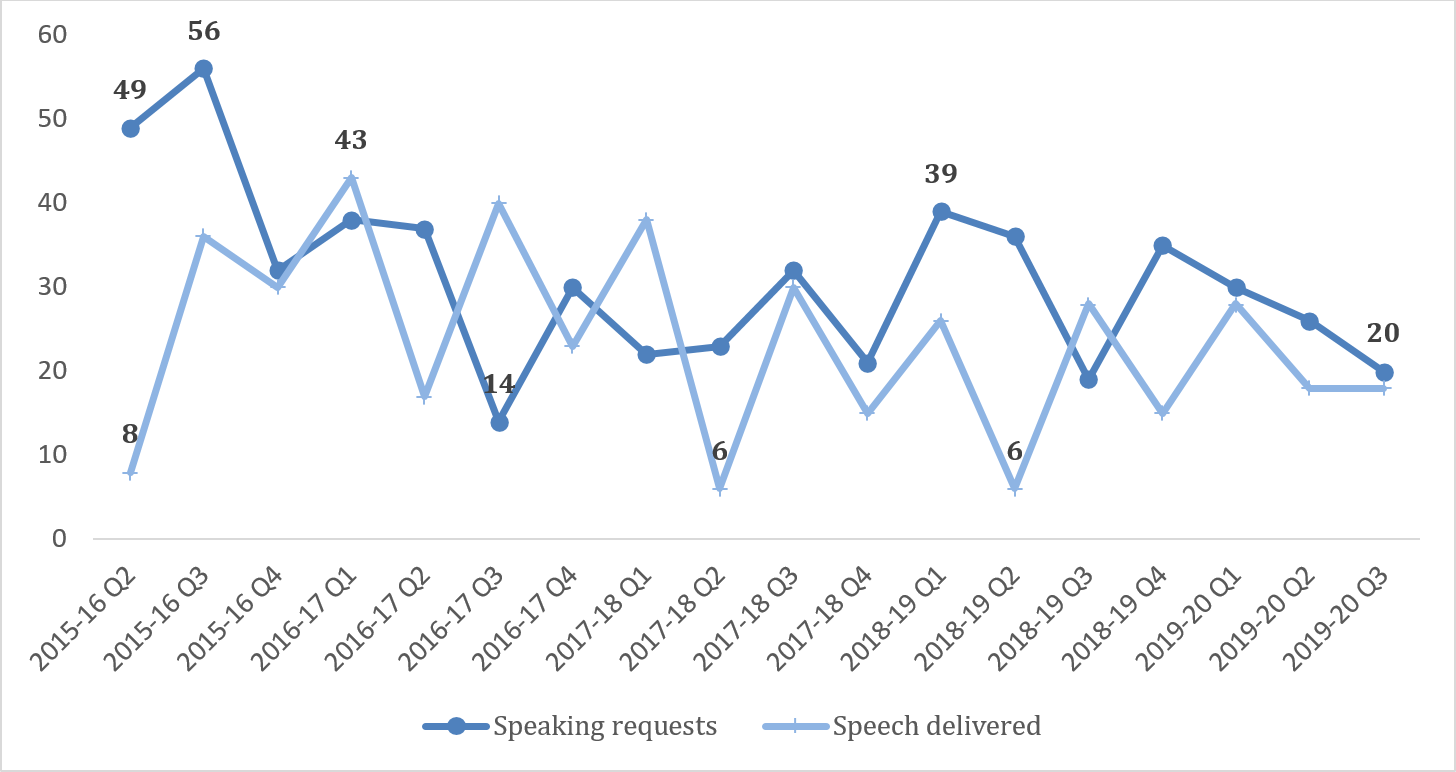

As shown in Figure 6, the OPC also receives speaking requests and has delivered numerous speeches to a wide range of audiences, such as schools and universities, the federal public sector, small and medium enterprises, the security industry, the legal industry, the information technology industry, among others.

The number of speeches given has not kept up with the demand for them; this would appear to substantiate external stakeholder’s claims that OPC has been less in recent years, and that this is possibly a result of resource constraints. An OPC staff has agreed with this, and noted that the Commissioner approved a new Terms of Reference for events committee that sets out new criteria for accepting/not accepting requests.

Figure 6: The Number of Speech Requests and Delivered Speeches

Text version of Figure 6

| Year | Speaking requests |

Speech delivered |

|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 Q2 | 49 | 8 |

| 2015-16 Q3 | 56 | 36 |

| 2015-16 Q4 | 32 | 30 |

| 2016-17 Q1 | 38 | 43 |

| 2016-17 Q2 | 37 | 17 |

| 2016-17 Q3 | 14 | 40 |

| 2016-17 Q4 | 30 | 23 |

| 2017-18 Q1 | 22 | 38 |

| 2017-18 Q2 | 23 | 6 |

| 2017-18 Q3 | 32 | 30 |

| 2017-18 Q4 | 21 | 15 |

| 2018-19 Q1 | 39 | 26 |

| 2018-19 Q2 | 36 | 6 |

| 2018-19 Q3 | 19 | 28 |

| 2018-19 Q4 | 35 | 15 |

| 2019-20 Q1 | 30 | 28 |

| 2019-20 Q2 | 26 | 18 |

| 2019-20 Q3 | 20 | 18 |

Source: Communications Quarterly Analysis

The OPC also tracks its distribution of materials, which include materials stemming from the youth initiatives work. In 2017-18, four Coed Communications e-blasts were distributed to 50,000 educators (per blast). The OPC has also had numerous requests for the resource and the graphic novel has been particularly popular. In 2017-18, the OPC received 96 publication requests for the graphic novel, giving out a total of 11481 graphic novels (9271 English, 2210 French).

The documentation indicates that OPC reached out to a number of youth-serving organizations, and was effective in distributing materials through this partnership approach. These partnerships have included Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS), Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada, Scouts Canada, Ladies Learning Code and The Students Commission Scouts Canada, We.org, and with civic education groups. The partnership with BBBS was fruitful, as they sent 6000 Social Smarts graphic novel to 116 agencies across Canada in phase 1Footnote 4. Ladies Learning Code also distributed 3000 graphic novels to their members via CodeMobile. Partnership with the Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada was another success. In FY 2017-18. The OPC was invited to exhibit at their annual conference in PEI (May 2018). They also publicly supported OPC’s reputation guidance (with regard to additional measures to protect youth).

The OPC continues to cooperate with other federal organizations through its participation in the Youth Engagement Collaborative, an initiative which brings federal departments working in this domain together. The documentation indicates that in 2017, a CRA insert promoting the OPC’s privacy resources were sent to 3 million Canadians along with their Canada child benefit notices.

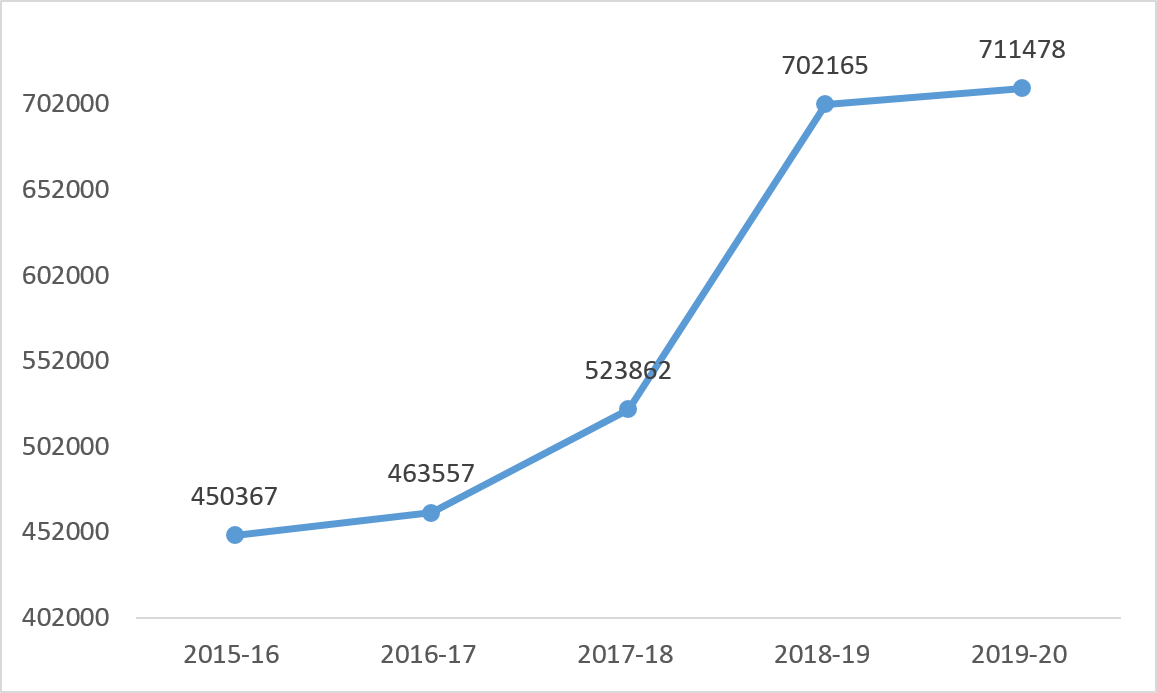

The OPC additionally provides public resources and information about privacy on its website. An increasing number of users have accessed the OPC webpages over the past few years (Figure 7).

Figure 7: OPC Average Yearly Recorded Web VisitsFootnote 5

Text version of Figure 7

| Year | Visits to the OPC Website |

|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 450367 |

| 2016-17 | 463557 |

| 2017-18 | 523862 |

| 2018-19 | 702165 |

| 2019-20 | 711478 |

Source: Communications Quarterly Analysis

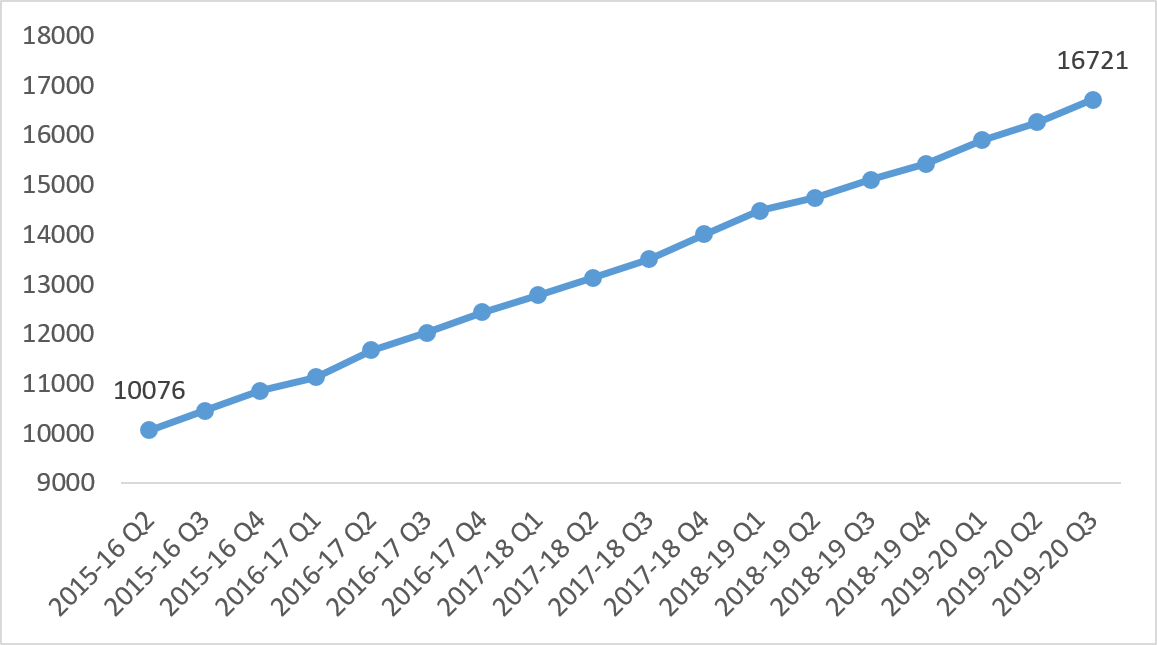

The OPC also maintains two Twitter accounts – the English language @privacyprivee and the French language @priveeprivacy. Followers for each account have continuously increased, and reached 16,721 in total as of Q3 2019-20 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: OPC’s Number of Twitter Followers

Text version of Figure 8

| Year | Followers (Twitter) |

|---|---|

| 2015-16 Q2 | 10076 |

| 2015-16 Q3 | 10465 |

| 2015-16 Q4 | 10869 |

| 2016-17 Q1 | 11140 |

| 2016-17 Q2 | 11676 |

| 2016-17 Q3 | 12036 |

| 2016-17 Q4 | 12443 |

| 2017-18 Q1 | 12786 |

| 2017-18 Q2 | 13141 |

| 2017-18 Q3 | 13514 |

| 2017-18 Q4 | 14018 |

| 2018-19 Q1 | 14486 |

| 2018-19 Q2 | 14748 |

| 2018-19 Q3 | 15115 |

| 2018-19 Q4 | 15433 |

| 2019-20 Q1 | 15905 |

| 2019-20 Q2 | 16271 |

| 2019-20 Q3 | 16721 |

Source: Communications Quarterly Analysis

Use of Resources

Among consulted stakeholders who responded to the evaluation survey, most (23/30; 77%) remembered seeing or receiving OPC communications related to the new guidance or information on consent under PIPEDA, either once or twice (37%) or multiple times (40%).

Most of the teachers who answered our survey did not remember receiving or seeing any information on youth privacy from the OPC (61%). Of those who had seen or received OPC communications (n=11), most (n=8) confirmed the communications were useful. However, they were also asked about where they find or would look for information on youth privacy. Their answers included the OPC, and extended to other organizations such as Media Smarts, Common Sense Media, HabilosMédias, Historica Canada's citizenship programs, Media Arts Literacy in Ontario, and the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. This is important, given that OPC funds some of these organizations, and suggests that even though they may not have seen OPC-branded materials, the work that the OPC funds is effective in reaching them through this leveraging.

Furthermore, internal key informants, including those with whom we conducted preliminary scoping interviews, explained that outreach activities are not limited to youth, but are absorbed within OPC’s overall outreach efforts.

It was difficult for many of the external key informants to speak much in detail about reach, though they echoed some of their similar comments about wanting OPC to amplify its voice in various fora. At the same time, it was clear that the OPC has effectively leveraged the work of organizations that do have a great presence, including funded organizations and provinces.

The provinces interviewed for this study indicated that they absorb efforts from the OPC in their own work, and then push it out through their own channels. One example of this was through school boards. The provinces also noted that the OPC can facilitate important introductions to large companies (e.g. Google) and international representatives, that provinces may have difficulty connecting to on their own.

Respondents to the survey of consulted organizations were asked what would be the most effective way for the OPC to make resources and information available to businesses, civil society organizations and other stakeholders regarding consent. Respondents’ suggestions included the following:

- Continue to make them available on the OPC website (and make navigation easy);

- Notify stakeholders via email notifications and social media;

- Hold regular update/review events on consent (e.g., hosting roundtables and meetings) for some direct stakeholder engagement;

- Disseminate information using plain-language messaging and in a variety of formats (e.g., video, visuals, etc.);

- Produce (more) material geared towards individuals and individual rights (not only for businesses);

- Participate in trade conferences and external sectoral events; and,

- Place media ads.

Awareness of Privacy Issues

Overall, when looking at the different dimensions of change, awareness is the aspect that OPC can be the most assured of its contributions.

Key informants agreed that the OPC had increased awareness of consent and youth privacy, while qualifying their comments in the knowledge that awareness of privacy issues has been elevated in the public consciousness overall. That said, there was consensus that OPC is indeed making a contribution to awareness.

Surveys conducted for this evaluation, as well as those conducted by OPC, bear this out. About 40% of respondents to the survey of consulted organizations confirmed that OPC’s resources on consent helped increase their organization’s awareness of issues of consent (when speaking to the five most used resourcesFootnote 6). This was the most frequently cited impact, followed by increasing organizations’ knowledge.

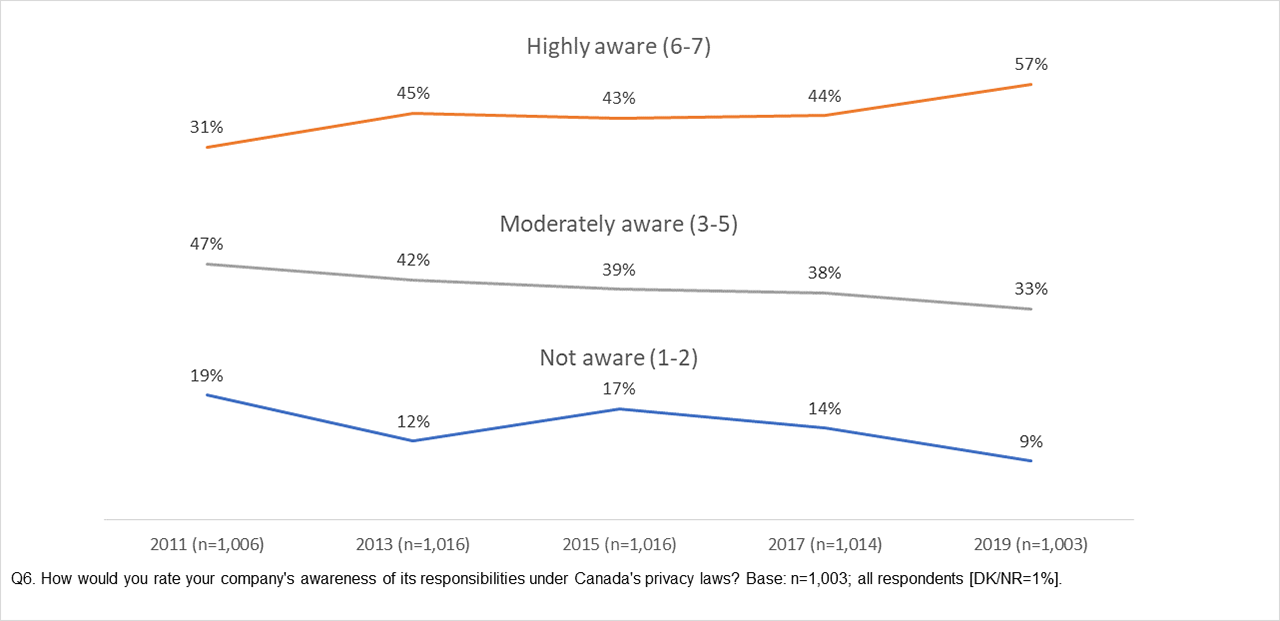

Similarly, more than half (57%) of businesses are aware of their responsibilities, according to the OPC’s 2019 Survey of Businesses. Figure 9 below, taken from that report, shows generally steady increases over time. This is an excellent result, and OPC has surely made a contribution to this progress.

Figure 9: Companies’ Awareness of Responsibilities under Privacy Laws (over time)

Text version of Figure 9

| Level of awareness | 2011 (n=1,006) |

2013 (n=1,016) |

2015 (n=1,016) |

2017 (n=1,014) |

2019 (n=1,003) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly aware (6-7) | 31% | 45% | 43% | 44% | 57% |

| Moderately aware (3-5) | 47% | 42% | 39% | 38% | 33% |

| Not aware (1-2) | 19% | 12% | 17% | 14% | 9% |

| Q6. How would you rate your company’s awareness of its responsibilities under Canada’s privacy laws? Base: n=1,003; all respondents [DK/NR=1%]. |

|||||

At the same time, the 2020 Survey of Canadians suggests that Canadians remain unsure of how their information is handled. About half (46%) feel informed about how their personal information is handled by companies, and just over half (54%) have not very much or no information at all about this. The majority of Canadians also feel they have not very much or no control at all over how their personal information is used by companies (61%) or by government (65%), according to that same survey.

Similar sentiments were reported by teacher survey respondents who indicate they are either somewhat (35.7%) or very concerned (46.4%) about issues related to youth privacy online. Most teacher respondents completely agree (82%) or somewhat agree (18%) there should be a greater focus on educating Canadians to be responsible and informed online citizens. The respondents’ top priorities related to overall youth privacy were basic awareness/introduction to online privacy (46%); learning to respect others’ privacy online (43%); privacy on apps and mobile devices (39%); privacy on social media (36%), and the way businesses gather information on youth (36%).

Desire to Change Privacy Practices

Key informants only had a few comments on desire. One noted that there is general agreement that youth privacy should be protected; there is not much debate on this issue in principle, only in practice. They also noted there was desire among youth for greater action on youth privacy issues. Similarly on consent, key informants reported that companies do want to stay in line with PIPEDA and overall privacy norms. However, they also want to be able to use the data they are capable of collecting, and sometimes struggle on how they can balance these two ambitions. It was also suggested that the strongest motivators for desire to change among business is profitability, clarity of responsibilities, and enforcement.

According to the OPC’s public opinion research, about a third of Canadians (in 2016, 2018, and 2020 respectively) expressed they were extremely concerned about the protection of their privacy. Furthermore, just over half (52%) do feel confident about their knowledge of the privacy implications of new technologies.

According to the survey of consulted organizations, the guidelines and findings of investigations are popular resources having the most impact on desire to change: about 44% of respondents indicate that the guidelines had an impact on their intentions or actions, 51% said the same about the results of investigations. Interviewees said these products also form the basis for discussions with youth.

Knowledge & Understanding of How to Change Practices that Impact Privacy

The large-scale surveys conducted by OPC continue to be the closest fitting evidence aligned to questions of improved knowledge and understanding of how to address privacy, although they do not speak to the consent model or youth activities in particular. Looking at the picture nationally, more than half (58%) of Canadians know how to protect their privacy rights, according to the OPC’s 2020 Survey of Canadians. Although, again, key informants stated that businesses do not always know how to apply in practice the knowledge gained from OPC guidance and resources.

Internationally, the OPC is seen to play an indirect role in influencing the work of other countries. Canada’s significant cooperation in international networks was said to help other countries to make their decisions based on information that OPC has shared.

Ability & Capacity to Protect Privacy

According to the 2020 Survey of Canadians, the majority (71%) have refused to provide personal information due to privacy concerns and adjusted privacy settings on a social media account. Nearly three-quarters (74%) have adjusted privacy settings on a social media account due to privacy concerns. More than a third of Canadians (41%) have actually deleted a social media account due to privacy concerns, and almost the same amount (40%) stopped doing business with a company that experienced a privacy breach.

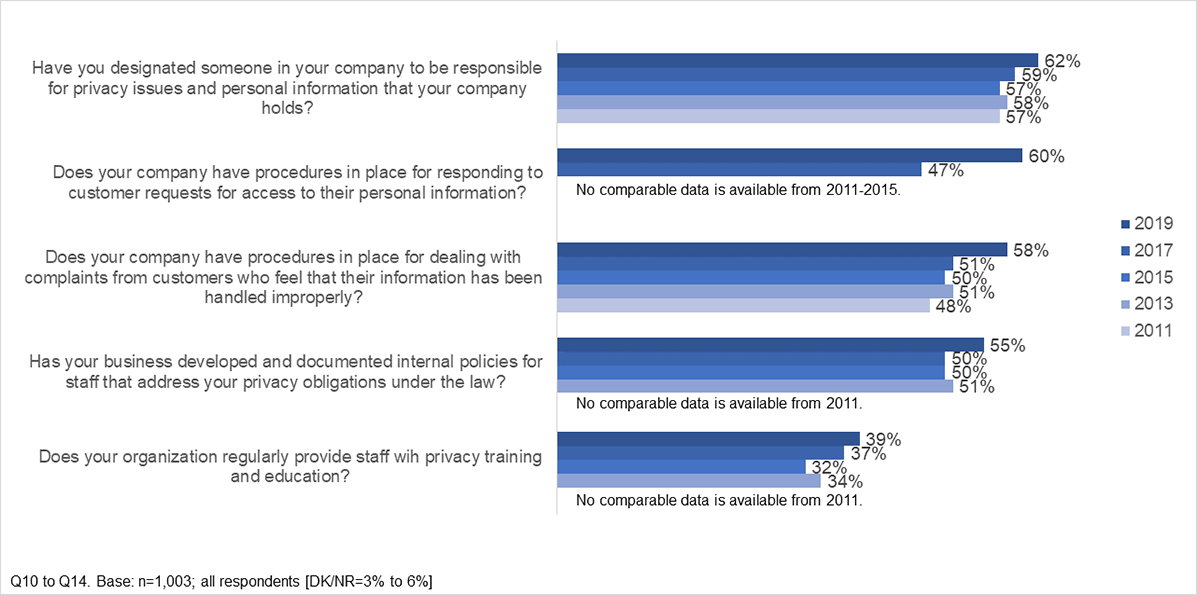

One of the more powerful pieces of evidence regarding behaviour change of businesses comes from the OPC’s survey of Businesses. Figure 10, taken from that report, shows steady increases in privacy policy practices being implemented by companies; including having a designated resource for privacy issues, procedures for dealing with privacy complaints, and documentation pertaining to privacy obligations under the law. Each of these are concrete expressions of actual ability and capacity to change:

Figure 10: Privacy Policy Practices (over time)

Text version of Figure 10

| Questions | 2019 | 2017 | 2015 | 2013 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you designated someone in your company to be responsible for privacy issues and personal information that your company holds? |

62% | 59% | 57% | 58% | 57% |

| Does your company have procedures in place for responding to customer requests for access to their personal information? |

60% | 47% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Does your company have procedures in place for dealing with complaints from customers who feel that their information has been handled improperly? |

58% | 51% | 50% | 51% | 48% |

| Has your business developed and documented internal policies for staff that address your privacy obligations under the law? |

55% | 50% | 50% | 51% | N/A |

| Does your organization regularly provide staff with privacy training and education? |

39% | 37% | 32% | 34% | N/A |

| Q10 to Q14. Base: n=1,003; all respondents [DK/NR=3% to 6%] |

|||||

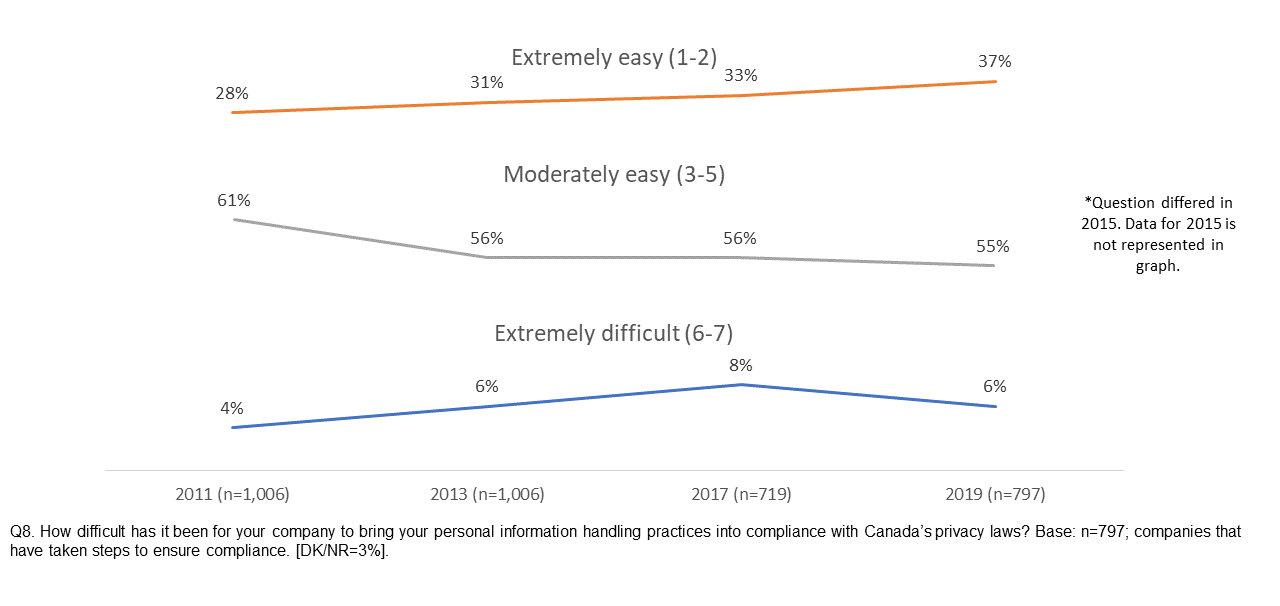

Continuing these positive trends, businesses also indicated an increasing ease with which they are able to comply with Canada’s privacy laws, as seen in Figure 11 taken from that report:

Figure 11: Compliance with Canada’s Privacy Laws (over time)

Text version of Figure 11

| Level of difficulty | 2011 (n=1,006) |

2013 (n=1,006) |

2017 (n=719) |

2019 (n=719) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely easy (1-2) | 28% | 31% | 33% | 37% |

| Moderately easy (3-5) | 61% | 56% | 56% | 55% |

| Extremely difficult (6-7) | 4% | 6% | 8% | 6% |

| * Question differed in 2015. Data for 2015 is not represented in graph. Q8. How difficult has it been for your company to bring your personal information handling practices into compliance with Canada’s privacy laws? Base: n=797; companies that have taken steps to ensure compliance. [DK/NR=3%]. |

||||

Influencing Policy Makers

Perhaps the most pertinent piece of evidence regarding OPC’s ability to influence changing practices in these two areas of focus is the comprehensive series of recommendations for modernizing PIPEDA as part of a study by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics (ETHI). This report, the 2016-17 Annual Report to Parliament on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act, included recommendations that touch upon both the consent model and youth activities. The Committee went on to agree with all of these recommendations in the government’s response to the 2018 report, Towards Privacy by Design: Review of The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. The OPC is thanked for its contributions to these documents.

While Bill C-11 is strictly outside of the scope of this evaluation, it is worth noting that two of the recommendations agreed to in the Towards Privacy report pertained to the enforcement powers of the OPC (namely recommendations 15 and 16Footnote 7). A reasonably direct line can be drawn from these recommendations to the greater enforcement powers put forth in the proposed Consumer Privacy Protection Act. Bill C-11 also incorporates many of the elements in the OPC’s consent guidelines.

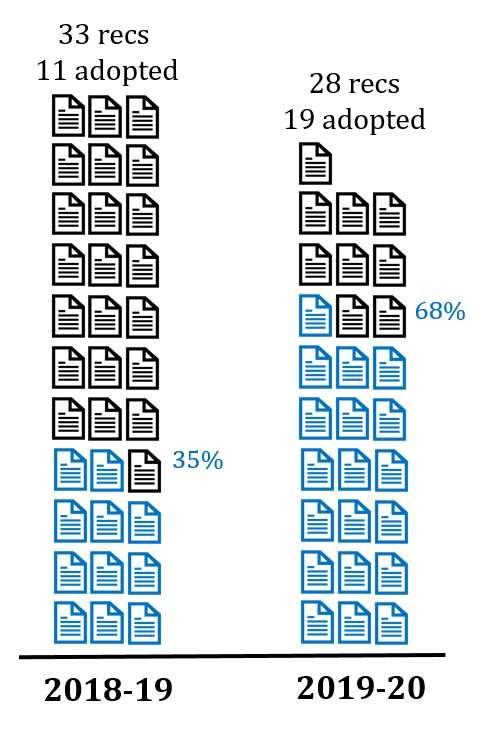

Figure 12: Adoption of Recommendations to Parliament

Text version of Figure 12

| Year | Adopted | Not adopted |

Total recommendations |

% of adopted recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-19 | 11 | 22 | 33 | 35% |

| 2019-20 | 19 | 9 | 28 | 68% |

Another youth-related example of such influence includes Bill C-26, the Tougher Penalties for Child Predators Act, which took up the OPC’s recommendation on creating a High-Risk Child Sex Offender Database that could be accessed by the public.

Indeed, Parliament has frequently requested the OPC’s input on various bills, studies, and issues (see Figure 12). In 2018-19, the OPC started to track the number of recommendations to Parliament that have been adopted. In that year, among 33 recommendations the OPC made, 11 were adopted by Parliament. In the following year, 68% (19 out of 28) of the OPC’s recommendations were accepted by Parliament.

Collaboration & Participation

The evaluation also sought views from key informants on the OPC’s collaboration with other organizations. Overall, key informants agreed the OPC has collaborated well with other privacy regulators (such as PTs), funded organizations, and other countries in regards to its privacy mandate.

The documentation notes ways in which the OPC actively participates in the international sphere of privacy policy and education, which corresponds with interviewees who pointed to the strength of the OPC’s international collaborative efforts. There are some examples in which international contacts have borrowed and adapted OPC materials, such as activity sheets and the graphic novel, including Israel, Croatia, and Sweden. Canada is also a founding member of the Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN) and has led a working group on enforcement that was said by interviewees to be a very helpful contribution to international efforts.

One constraint raised by interviewees was the uncertainty surrounding increasing collaboration and the possible conflict of interest with the OPC’s investigations side of work, i.e., concern that raising an issue could generate scrutiny, even if one is trying to ‘do the right thing’. In general, stakeholders would like to see more collaboration overall.

3.3 Efficiency & Lessons Learned

EQ5: To what extent have processes and resources (time, money, people) been adequate to achieve outcomes?

FINDING: OPC is a small organization, with a big mandate, and it addresses complex issues. Resource constraints are an overall limitation to the OPC’s work. Funding youth organizations to carry out work on behalf of the OPC has worked well to leverage resources efficiently. The OPC did not complete 90% of its planned guidance work by 2021, leaving stakeholders wanting more in the areas of de-identification, artificial intelligence, online reputation, and educational apps and platforms.

Financial & Human Resources

The OPC has used Grants & Contributions to leverage the expertise and networks of youth organizations, and many stakeholders commented that it was an effective way to expand the OPC’s limited resources devoted to these activities. The following (Tables 4 and 5) denotes the projects funded this way.

| Years | FTEs | HR CostsFootnote 8 | Operating | Communications | One-off CommunicationsFootnote 9 |

Total Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 1.1 | $90,740 | $2,500 | $93,240 | ||

| 2016-17 | 1.1 | $90,740 | $53,693 | $2,500 | $146,933 | |

| 2017-18 | 1.1 | $90,740 | $2,500 | $93,240 | ||

| 2018-19 | 0.3 | $32,740 | $2,500 | $35,240 | ||

| 2019-20 | 0.3 | $32,740 | $2,500 | $35,240 | ||

| One-off | $22,700 | $22,700 | ||||

| Total | 3.9 | $337,700 | $53,693 | $12,500 | $22,700 | $426,593 |

| Years | FTEs | HR Costs | OperatingFootnote 10 | One-off OperatingFootnote 11 |

Total Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 0.25 | $22,000 | $15,700 | $37,700 | |

| 2016-17 | 0.25 | $22,000 | $15,700 | $37,700 | |

| 2017-18 | 0.25 | $22,000 | $15,700 | $37,700 | |

| 2018-19 | 0.25 | $22,000 | $15,700 | $37,700 | |

| 2019-20 | 0.25 | $22,000 | $15,700 | $37,700 | |

| One-off | $95,160 | $95,160 | |||

| Total | 1.25 | $110,000 | $78,500 | $95,160 | $283,660 |

The following (Table 6) details the projects funded through Contributions Agreements.

Resource Constraints and Response

A key theme that came up in response to many of the interview questions, and across stakeholder groups, is that OPC is a small organization, with a big mandate, and need to address complex issues. The human resource constraints in particular were noted as an overall limitation. Internal interviewees discussed the need to shift resources between priorities, especially as new ones unfolded. There was a general sense of being stretched really thin.

At the same time, we heard about efforts to use available resource strategically. As mentioned, funding youth organizations to carry out work on behalf of the OPC has been one effective way to do this. Leveraging partnerships with national organizations in order to operate efficiency has indeed been an intentional planning effort, as identified in the communications and outreach strategy documentation reviewed for this evaluation.

Competing Priorities and Trade-Offs

Given resource constraints and competing priorities, the evaluation also sought to examine work left uncompleted, to understand the trade-offs made by the focus on consent and youth over this period. As discussed earlier, emerging issues in the dynamic environment of privacy have required OPC to respond and pivot where attention to unforeseen issues have arisen. There was appetite to explore what stakeholders cared about when such choices were made. These evaluation questions and indicators are most clearly expressed by the topics for which the OPC planned to develop guidance, as laid out in the 2018-19 Departmental Plan. The Plan states, “While we cannot promise to fulfil this wish list as quickly as we would like, we will strive to complete 90 percent of it by 2021, taking into account our workload and resources.” By the summer of 2020 (the end date of this evaluation’s scope), only 8 out of the 30, or 27%, had actually been completed (see Table 7). They comprise:

Table 7: Total Wish List and Guidance Completed

- Consent (including forms of consent)

- Subsection 5(3) no-go zones

- De-identification

- Big data, artificial intelligence & robotics

- Genetic information

- Internet of Things

- Connected cars

- Smart homes

- Privacy enhancing technologies

- Surveillance technologies

- Privacy at the border (smart borders)

- Necessity and proportionality in the public sector

- Online reputation

- Privacy and social media

- Educational apps/platforms

- Biometrics & facial recognition

- Cookie-less tracking

- Blockchain

- Digital health technologies

- End-to-end encryption

- Social engineering

- Trans-border data flows & cloud

- Open government

- Accountability maturity model

- Breach notification and Receiving a Privacy Breach Notification

- Data brokers

- Fintech

- Sharing economy

- In-store tracking

- Behavioral economics

Note: Products that have been completed are presented in blue underline and have been hyperlinked to the original documentation on the OPC’s website.

Some stakeholders referred to these products by name, and others spoke more generally to these subjects. Their sum feedback would suggest the following areas were where absences were identified:

- De-identification (3);

- Artificial intelligence (part of 4);

- Online reputation (13); and,

- Educational apps/platforms (15).

It is important to note, however, that this list does not mean that no work was conducted in these areas, but rather that guidance was not issued on the topic. In these specific cases, stakeholders had hoped to see guidance issued and/or more work conducted on these topics. (See also the feedback on ‘gaps’ in Section 3.1, EQ2). Internal stakeholders did not suggest these topics had waned in significance, but rather tough choices have had to be made given limited resources, coupled with the necessity to remain agile to tackle new and urgent issues as they transpired.

EQ6: What lessons can be carried forward? What could be done differently next time?

FINDING: Three lessons have been identified, in the areas of transparency, pragmatism, and planning for evaluation.

This section is intended to synthesize issues across the evaluation into succinct lessons learned that can help to inform future planning for OPC.

Transparency

Letting people know what the OPC is working on, and thinking about, can enable more meaningful engagement with the OPC and the issues it intends to promote discussion upon. This also helps stakeholder organizations to work with their memberships, clients, constituencies and target groups to modernize their approaches before guidance is issued and surprises them.

This openness is not suggested simply for the principle of it, but because it ultimately supports the capacity to change; that we have sought to understand through this evaluation. In relation to the next lesson, opportunities to help shape this guidance might also ensure its pragmatism.

Pragmatism

Ensuring guidance is practical and feasible to implement promotes uptake and adherence. We heard that additional business and technical expertise would contribute to the viability of guidance that is issued. We were also told that recognizing and accounting for variations across sectors would go a long way in helping organizations be able to apply guidance in their own contexts.

Planning for Evaluation

Sometimes the process of undertaking an evaluation reveals findings in and of itself. As was discussed in the limitations section, we were restricted in our ability to directly reach stakeholders who did not consent in advance to being contacted for the purposes of providing feedback. In the future, building in plans for feedback from the beginning of an initiative will facilitate more a robust assessment thereafter. Gathering feedback during or immediately following these types of exercises may also be more meaningful and practical as well.

4.0 Conclusions and Recommendations

CONCLUSION: Feedback to OPC’s consultation processes were generally positive, and overall, the thrust of feedback was wanting more: more consultations, more time to engage, and more opportunities and channels to provide input.

RECOMMENDATION 1: The OPC should revisit its process and approach for consultations.

This would be undertaken with a view to:

- Ensuring the process is structured, specific, and clearly defined for all who are involved;

- Engaging stakeholders early, allowing for adequate time to provide input;

- Giving stakeholders the opportunity to react to draft guidance;

- Consulting with youth specifically as appropriate;

- Building in consent to be contacted for feedback into consultation processes; and,

- Developing a list of stakeholders that can be approached directly on future work as it unfolds.

Conclusion: One of the more persistent criticisms of the organization coming out of the evaluation, especially in the area of the consent work, was a sense that the OPC is out of touch with the private sector. Incorporating business experience and knowledge would bring greater credibility to the OPC’s guidance, and might also make it more feasible to implement.

RECOMMENDATION 2: The OPC should identify ways to integrate industry expertise.

Options for this might include an external business advisory committee, re-visit lessons learned from historical previous committees that were in place, and take the best practices available from those experiences. Targeted recruitment of staff from the private sector might also help, as would clarifying and enhancing the role and visibility of business advisory directorate.

Conclusion: Leveraging the work of youth organizations was considered both effective and efficient ways of extending OPCs reach in the domain of youth privacy. At the same time, there was also criticism that OPC might be somewhat disconnected from youth as a target group. Greater priority placed upon reaching youth and greater resources devoted to these efforts would likely address some of the questions raised above.

RECOMMENDATION 3: The OPC should establish specific mechanisms to hear from youth.

This might include options such as establishing a youth advisory council, and/or presence within major youth privacy fora. Such undertakings would be meant to promote OPC’s visibility within this space, and also to hear first-hand the concerns of youth and their proposed solutions. Duplicating efforts of funded organizations to educate youth on privacy issues should be avoided.

Appendix A - Evaluation Matrix: Consent Model & Youth Initiatives

| Evaluation Issue & Question | Indicators | Data Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document & Data Review |

Internal Key Informants (n=5) |

External Key Informants (n= 20) |

Survey of Teachers |

Survey of Businesses & CSOs |

OPC’s POR Surveys |

||

| EQ1: To what extent have the Strategic Privacy Priorities been useful in guiding the activities of the Initiatives? | Evidence SPPs were used in planning activities | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Extent of alignment between activities undertaken and corresponding SPPs | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Opinions on alignment to needs and identification of gaps | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Perceptions of how well the strategies will fulfill the OPC’s purpose | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| EQ2: How has the work of these Initiatives adapted to emerging areas of need and relevance? | Requirements to adjust plans /products | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Ratio of completed planned work to unplanned work | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Mechanisms in place to facilitate flexibility | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Evaluation Issue & Question | Indicators | Data Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document & Data Review |

Internal Key Informants (n=5) |

External Key Informants (n= 20) |

Survey of Teachers |

Survey of Businesses & CSOs |

OPC’s POR Surveys |

||

| EQ3: To what extent has the work of these initiatives met the needs of stakeholders they were intended to address? | Alignment of the volume of information requests and complaints to the work of the initiatives | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Use and usefulness of guidance/advice/products produced | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Evidence that advice / guidance was used by stakeholders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| EQ4: To what extent are target populations being reached and influenced? | Evidence of change in behaviour(s):

|

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Evidence of reach:

|

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Evaluation Issue & Question | Indicators | Data Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document & Data Review |

Internal Key Informants (n=5) |

External Key Informants (n= 20) |

Survey of Teachers |

Survey of Businesses & CSOs |

OPC’s POR Surveys |

||

| EQ5: To what extent have processes and resources (time, money, people) been adequate to achieve outcomes? | Opinions on resource adequacy | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Extent of planned work not completed based on necessity to pivot | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Opinions of efficiency of the strategies/processes employed by OPC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Evidence of cross-functional sharing and organizational capability alignment | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Suggestions for process improvements/alternatives | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| EQ6: What lessons can be carried forward? What could be done differently next time? | Identification of lessons learned & best practices (including other jurisdictions) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Replicability of lessons | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

Appendix B – Key Information Interview Master Guide

Do you have any questions before we begin?

1. Would you say your work relates most closely to:

- Consent?

- Youth privacy?

- Both?

Introduction

2. Please briefly describe your role. In what capacity is the OPC’s consent and/or youth privacy work relevant to you or your organization?

Question 2 applies to the following stakeholder groups: OPC key informants (internal); associations and civil society organizations; subject-matter expertsFootnote 12; provincial and territorial representatives; and, international counterparts.

Relevance

3. How were the Strategic Privacy Priorities used to plan activities related to consent and/or the youth initiatives?

Question 3 only applies to OPC key informants (internal).

4. In your view, to what extent do the consent and youth privacy activities undertaken by the OPC respond to ongoing needs? Are there major gaps or issues left unaddressed in the work OPC does in those areas?

Question 4 applies to the following stakeholder groups: OPC key informants (internal); associations and civil society organizations; subject-matter experts; provincial and territorial representatives; and, international counterparts.

5. The mission of the OPC is to protect and promote the privacy rights of individuals. The OPC oversees compliance with the Privacy Act, which governs the personal information handling practices of federal departments and agencies, and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Canada’s federal private-sector privacy law. To your knowledge, to what extend has the OPC’s work regarding consent and youth privacy in the last five years contributed to fulfilling that mandate?

Question 5 applies to the following stakeholder groups: OPC key informants (internal); associations and civil society organizations; subject-matter experts; provincial and territorial representatives; and, international counterparts.

6. To what extent has the OPC’s work under the consent and youth initiatives changed as a result of emerging areas of need?

- What happens when a new need emerges? To what extent can the OPC pivot and adapt?

- Over the last five years, to what extent has planned work not been completed due to changes in direction or focus? In your opinion, was this shift justified?

Question 6 only applies to OPC key informants (internal).

7. In your view, to what extent is the OPC able to adapt to new and emerging needs and issues? How effectively has the OPC responded to new issues in the last five years?

Question 7 applies to the following stakeholder groups: associations and civil society organizations; subject-matter experts; provincial and territorial representatives; and, international counterparts.

Performance

8. Has the work done by the OPC on consent and youth privacy impacted the nature of information requests and/or complaints received by the OPC? How so? (i.e., does the content of them tell us anything about OPC’s influence?)

Question 8 only applies to OPC key informants (internal).

9. How useful is the OPC’s guidance and advice related to consent and youth privacy? How useful are the OPC’s products in those areas?

Question 9 applies to the following stakeholder groups: OPC key informants (internal); associations and civil society organizations; subject-matter experts; provincial and territorial representatives; and, international counterparts.

10. Have you used consent or youth-related resources made available by the OPC?

- If so, how? How satisfied were you with those resources? How did those resources benefit you or your organization?